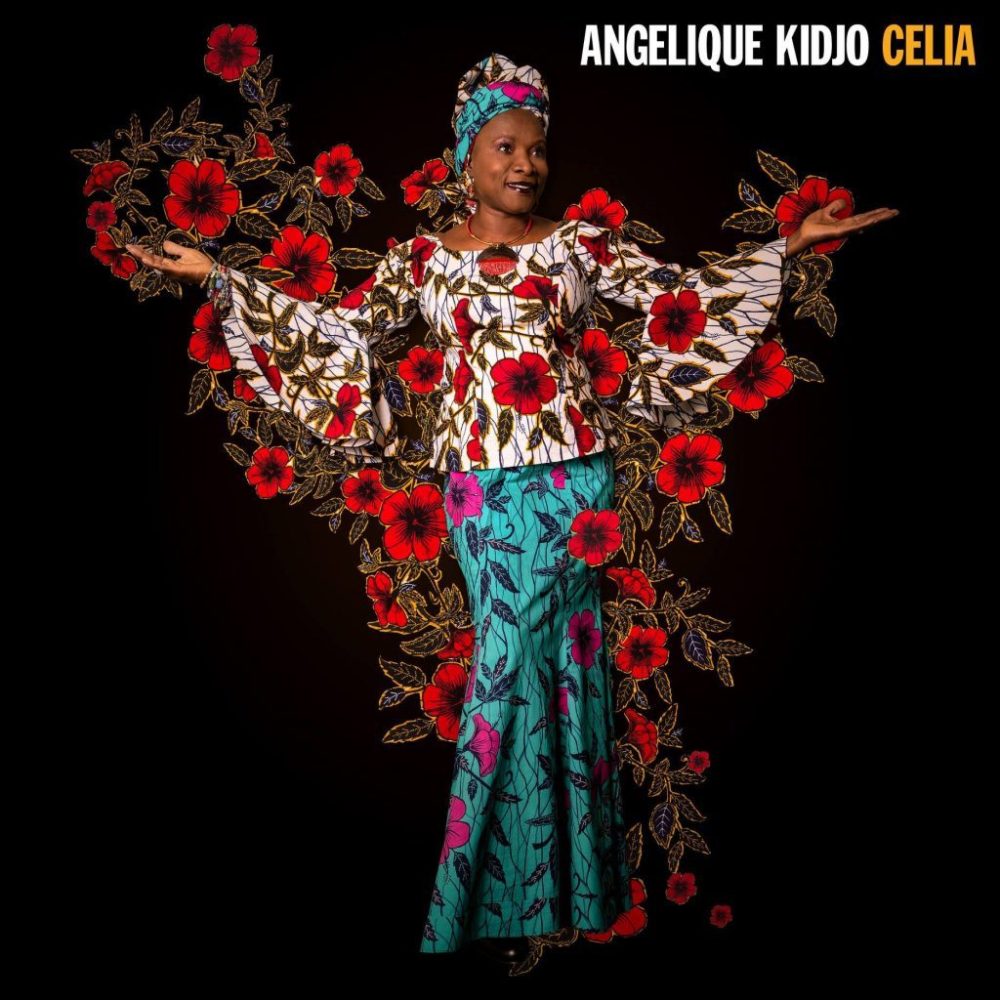

Angelique Kidjo’s new album is an explosive, energetic and imaginative tribute to Celia Cruz. It comes in the wake of Kidjo albums that have explored connections to Brazil, Haiti, orchestral music, and the Talking Heads, among others. She is constantly finding new ways to channel her talents as a visionary, an arranger, and one of the iconic voices in today’s African music. Afropop’s Banning Eyre recently visited her at her Brooklyn home. He was fresh from Seattle’s Museum of Popular Culture and its annual pop music conference on the theme “Music, Death and Afterlife.” So the conversation started there…

Angelique Kidjo: Hey. How are you? Are you from the afterlife or the dead? Which one do you choose?

Banning Eyre: Well, I think it’s appropriate that we start out by talking about the afterlife, because with this album you are helping to keep Celia’s afterlife going.

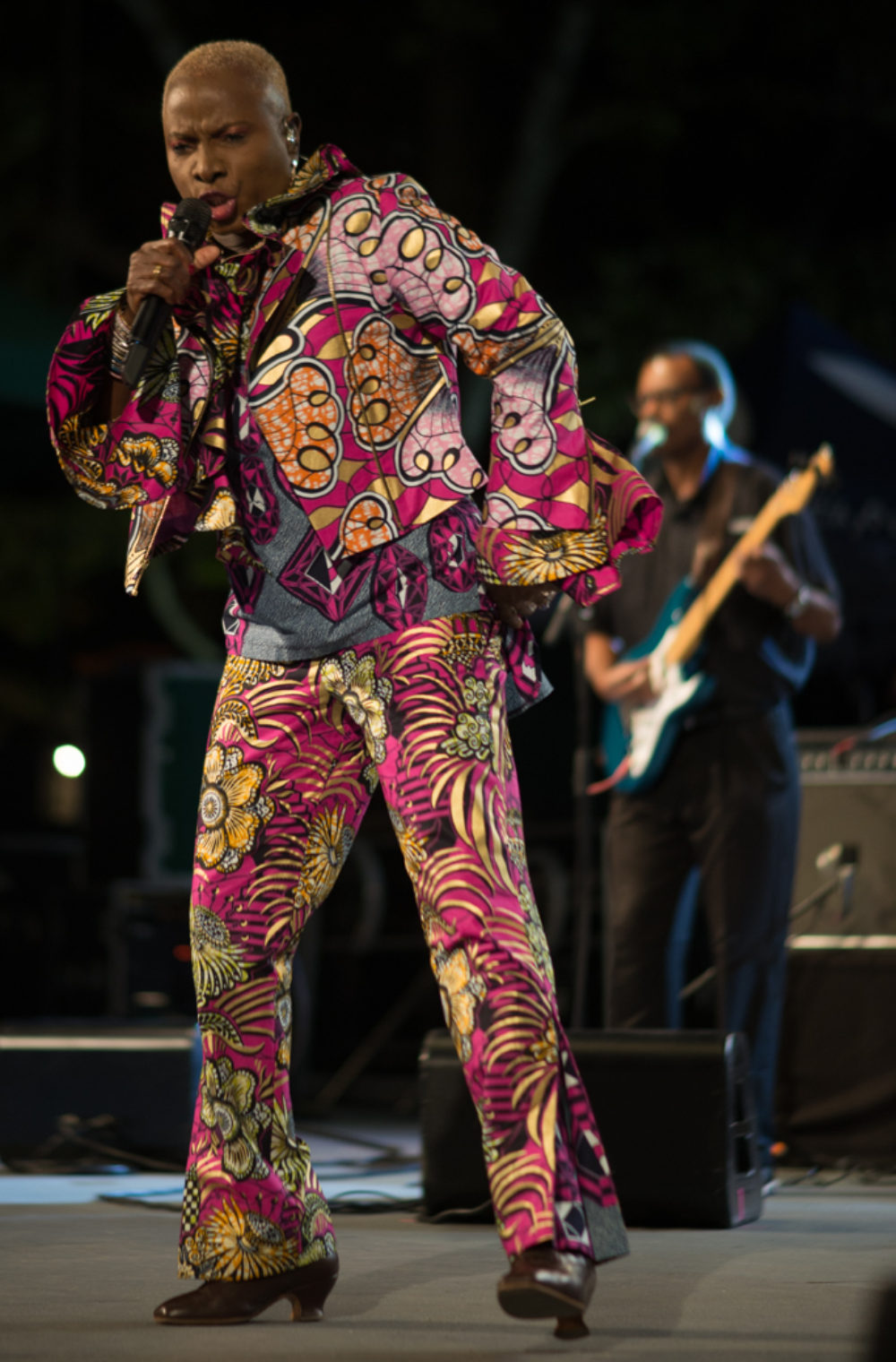

She’s a great artist. Why should we forget the ones who really empowered us for so long? Celia Cruz was an artist that reached beyond Afro-Cuban culture. There’s not one place in this planet where you can hear Celia Cruz and faces don’t just light up. She’s that kind of person. When she comes on stage, she gives 150 percent. She exudes and embodies joy.

This is an artist you listened to back in Benin, right?

Since I started dancing salsa, I have always wondered, when is a woman’s voice going to come to this music? Because it was all men. Even Bembeya Jazz, even Youssou and Super Etoiles—all these salsa bands had only male singers. All of them, all the way to Aragon de Cuba and Irakere. All those people were male. So to me, “Well, to do salsa, you’ve got to be a guy.”

And then Celia Cruz came in and flipped that story around, in a positive way, where suddenly you said to yourself, “Well, even in this field filled with guys, a woman can come and make her point clear loud enough and powerful enough for me as an African girl to say, ‘I can do anything I want.’”

That moment came while you were still back in Benin?

Sure. In Benin, a lot of bands came to play. Johnny Pacheco came to Benin, Chocolate, Aragon de Cuba… a lot of salsa bands came. I know Celia was there because I remember seeing her on stage. She walked on and I was like, “She’s not a backing singer. She’s front and center.” And that was a defining moment where you realize two things: As a woman, you can do anything. You just have to do it. Also, you can exude joy and create an extravaganza and anything you want. Basically you can be whoever you decide to be on stage.

Then I met her in the late '90s in Paris. She came to play, and a friend of mine, a journalist from Radio Nova, Remy Kolpa Kopoul, said to me, “Hey, Celia is playing in Paris.” And I said, “If this is a joke, I don’t find it funny at all.” He said, “It’s not a joke. So do you want to come or stay and argue with me?” So with my husband we took the car and arrived. Everybody was on stage. The musicians were playing before Celia comes on stage as usual.

So I met her in the dressing room. Remy introduced her to me. He said. “This is a new African singer from Benin.” And she said, “Benin. I went there!” And I said, “Yes, I know. I saw you there.” And then I started singing, “Quimbara, quimbara…” And she said, “Oh, you’re going to sing tonight? You come on stage and sing with me.”

Really?

Yeah. She invited me on stage. And I didn’t know that song that well. I just sang what I used to sing when I heard it. I don’t speak Spanish. I didn’t know anything about it. But she invited me to the stage. Her husband’s face just fell on the ground. “Who is this lady? We didn’t rehearse this. What is this all about?” And I don’t know what Celia said to her husband, but he was like, “O.K., you’re the boss anyway.” So I did “Quimbara” with my broken Spanish and she was laughing so hard. It was amazing. She was just like, “This girl is not afraid of nothing.” And I wanted to say to her in Spanish, “I take the example from you. You’re not afraid of anything so why should I be?”

And I left the stage thinking, “You’re making a fool yourself not singing right.” And she picked up the song from the beginning and sang the whole thing. From that point on, I met her two or three times at the Grammys. She would be calling me and we’d sit down and speak half Spanish, somehow. She was so welcoming in her heart. That’s something that was very important to me that I remember from the few times I spent with her, how she made you feel special when you were in her presence. And I think that’s why everybody, male or female whatever way you come from, she came to this country and she managed to reconcile through music from home on.

That’s wonderful that you had those experiences with her directly.

Yes, but I should’ve done this while she was still alive.

Well, she died in 2003. When did the idea for this album come about?

It was originally a project I put together for Celebrate Brooklyn. Because I’ve been talking about Celia Cruz for so many years, and people would say to me, “You have something in your voice that reminds me of Celia. You have to do something about Celia.” I would say, “I’m thinking about it. When the time is right, I will do it.”

And then when I was asked to play at Celebrate Brooklyn, I came with the idea of doing a tribute to Celia Cruz. That’s how the whole thing started. So I put the band together with Pedrito Martinez, and he found backing singers and the horns. We put everything together, and we did that show in Brooklyn here, and it was a huge success. Philip Glass was at the show and he said, “I never knew you could do this. You can do anything. Why don’t you do an album?” And every journalist I met said, “We’re waiting for the album.” I was just doing a show, but then it started getting into my mind. I had to think about it. I had to be inspired. What was important for me was to go back to the '30s, the '40s. She started with the band Sonora Matancera in Cuba. That’s when she started singing all those orisha songs.

That was something that was very important in my meeting her. She was so proud of her African heritage that she sang it. She just embodied that, as if to say, “I didn’t ask to be born here. I happen to be here, but my ancestors, I know where they come from.” And she sang those songs in a very elegant way, celebrating her African roots. So when I started working on the album, that was the direction we wanted to go with the producer. We chose carefully all the songs. To make sure that things are accurate, but also more modern, to create a balance while telling the story of her African heritage that we share together.

That’s very interesting. Because I know that when she first sang those Santeria songs, she got some pushback.

Of course.

There was hesitation about African religion. And obviously this is something you’ve dealt with all your career, coming from the land of vodun and all that. Celia was a real champion of that kind of tradition. And I would love you to talk about what it means to bring that aspect forward in today’s context when so much rising evangelism is trying to push all that stuff aside.

Well, you can’t push all that stuff aside. They were there before the evangelists came. The Greeks. Look at the gods of the orishas and you take Zeus and all of them. They have the same characteristics. They are the same. So why should we accept the existence of the mythology of the Greeks and not accept the mythology of the orishas?

That certainly makes sense, but don’t you feel that there’s a lot of pressure coming down on these traditions now. Look at Brazil now, with this new president. He is very hostile towards African religion. In Brazil!

It’s going to come and it’s going to go. Because those cultures and beliefs were there before anyone else came in. It was there before Catholicism. It was there before anything. Human beings live in nature. When they come to nature, they want to understand their surroundings. That’s what all these religions come from. All those gods are elements. Water. Air... All the things they could not explain. When they first heard the thunder, they said, “God is coming to punish the ones who are not doing good.” It’s the same thing with the Greeks. You cannot be a human being without spirituality. So the spirituality you find in nature is surrounding you all the time. We are part of nature, and nature is challenging us to also find our axis, how we are linked to the earth, how we as human beings can interact with and benefit from nature. So all those religions, that is what they are based on, and you cannot say that evangelism is better than anything else.

What is a religion doing? A religion for me should empower people to live their spirituality freely without any agenda. Right now, all the organized religions have just been there to destroy people’s free will to decide. God has become in the new era of religion today, a monster that kills. Because you have the Muslims who say we kill in the name of Allah. And then you have the Western forces that killed because they think they are superior. God has nothing to do with killing. The most important message of God is that you show love one another. And where is that today in the religion we have? How can you say you believe in God and you follow none of the rules of God?

I’m glad to hear you say that, and one of the reasons that these traditions will never go away is the music. It’s so powerful. These songs, they are never going to go away, right?

But every religion has songs.

True, though you could argue that some are better than others…

When somebody dies, you go to a Catholic Church and sing a song for it. They sing in Latin or the sing in other languages. It’s a ritual that every human being lives with. Imagine a world with no music. We would all go crazy. And those rituals are important to remind us of our time on earth. You are talking about a conference about death music and afterlife, it’s the constant quest of man. Because we all know that we come and we have an amount of time to spend here, and when they were all to leave. And between when you’re born and when you die what matters is what you bring to the table for your fellow human beings. What will you be remembered for and what you leave for your own family? What is your legacy? If your legacy is hate, you have to stand for it. If your legacy is love… We have a multitude of choices, and the beauty of God is giving us the free will to choose. And that’s something you can’t take away. If you brainwash people, the day they wake up, they won’t want it anymore, and they will go. That’s just the way it is.

Coming back to the record, when did you do that tribute concert for Celia?

Two summers ago.

And that’s what led to the record.

Absolutely.

I noticed something interesting about your voice in listening to this. I’ve heard you sing Miriam Makeba, Bella Bellow, even David Byrne. But you and Celia, your voices really match. There’s something about your voice that feels very close to Celia’s. It’s a perfect fit.

That’s what a lot of people say. And pretty much all those songs, it was even the same key with Celia.

So this was fated. Destiny.

It was meant to be. And you know, when she moved from Cuba to New York, she lived on the same street I lived when I came to New York, West 53rd between 8th and 9th. The same block. Destiny it is.

When it came to arranging these songs for recording, you made some interesting choices. It seems like you really Africanized the sound. I hear Congolese guitar. I assume that’s Dominic James. And I hear Tony Allen bringing in the Afrobeat feel. Is he the drummer on the whole album?

Yes.

Can you talk about the process you went through in putting together these arrangements. I understand you were working on this at the same time as you were doing your version of Remain in Light.

Yes, I was doing Remain in Light too. It’s weird. I can’t exactly tell you the sequence. I was doing both of them together and it was really a matter of the one that’s ready first will come out first. For Celia…. Like the song “Quimbara” is in 4/4, but behind that 4/4, I hear a 6/8. I’ve been doing a lot of music and understanding a lot of rhythm from a lot of stuff. The clave that comes with the slaves from Africa is the 6/8 clave, all across the planet. And that 6/8 is so flexible that you can multiply it or cut it or expand it anyway you want. So for me, it was easy. Anytime I’m doing salsa, I take it somewhere else because I hear something else in there. So it was important to do with this one with David Donatien, the producer, because both of us knew that we could not do this album as pure Cuban salsa. The Cubans do it better than anybody else, so what’s the point of copying what they do?

What was interesting to me as an artist was to bring it back to where it all started. Because salsa, guaguancó—all of these music start with Santeria music. So it comes back to where everybody comes from. So the best thing to do was to put my voice out there with a little arrangement, just the core of it like that with a little bit of percussion and the producer takes it from there. That’s why I wanted to work with the Gangbe Brass Band.

Are they doing the horns? I haven’t actually seen the sleeve notes for this album yet.

Yes. It’s a mixture. So the thing is, the clave, they can sleep on it and come back up to it the next morning. [Laughs].

Did you record Gangbe in Benin?

No. We recorded them in Paris actually. Meshell [Ndegeocello] didn’t come. She recorded here. Tony and I were in the studio in Paris with other musicians. Most of the vocals, I started them here in my studio in Brooklyn. Then I re-sang them of course live in the studio in different settings. So it’s interesting to see how David and I were on the same page on the way to do this. The only way to really pay tribute to Celia Cruz was to bring to light her Africanity—which she never shied away from—and to celebrate it. Who better to do that than an African artist?

I mean, I don’t want to copy. I can’t be Celia. Celia is the queen of salsa. She will always be. Nobody can be Celia. But as an artist, I wanted people to remember her. I don’t want her to be forgotten. Because she has given so much to all the communities, every community from Latin America to Africa to Europe to America, around the globe, even to Japan. So she’s that kind of artist that through her energy, her persona, her joy, and that word azucar, which is life is sweet. Everything can be sweet if you decide to go with it. You can choose the bitter if you want, but me, with Celia, I choose the sweetness of life. How much more positive can you be? It’s impossible.

The album has tremendous energy. I think it will be part of her legacy now because it’s such a strong tribute, and you’ve added so much by reconnecting with Africa. I find it especially cool to hear Tony [Allen] in there, because Nigerian music like Afrobeat is not as connected with the salsa Congolese rhythm spectrum…

Yes, but it comes from there too. Yoruba comes from where? Nigeria. In the rhythm of the words you have Afrobeat.

O.K., but it’s not what you expect to hear in a salsa setting.

[Laughs] Well, he knew salsa. There’s not one person who lived in Africa that never heard salsa and never danced to salsa. Even the English-speaking countries, everybody was infected by salsa. It’s impossible to have any party in West Africa where I come from without salsa. Don’t even think about it. You can play funk. You can play whatever you want. But everybody’s waiting for the salsa moment and then the dance floor becomes a sea of people swirling, dancing and singing loud. Come on!

I’m interested in your process of choosing songs. Because Celia has such a large catalog. Let’s listen to the originals of a couple of songs you chose.

“Bemba Colora” plays on a laptop. Angelique sings along for a couple of lines.

That is Africa right there. [Sings the percussion perfectly] That’s it. Africa is right there.

That song “Bemba Colora” is coming out of Santeria.

Directly. And also, “Bemba Colora” is about color. It can be anybody’s color. People used to criticize Celia, saying she’s not beautiful, she has big lips. And the more they said that, the more she emphasized that mouth. She sings, “Look at my lips. I can put any color I want on them. I can put red. I can put blue. I can put purple in my hair.” She created all that persona to just show people you can be a chameleon. You’ve got so many colors out there. Don’t be boring. Be flamboyant. That’s what “Bemba Colora” is all about. You want to wear purple on your head? Go ahead. Red? Go ahead. Blue? Go ahead!

Then there’s “Quimbara.” [“Quimbara” plays on the laptop.]

That’s the beginning where everybody started in Africa. Whenever you hear that opening, everybody’s up. Before she starts singing, everybody’s standing. We are always dancing on that groove. Just the percussion gets people started. They know what’s going to happen. And when she starts singing, everybody starts rolling around. That’s when we start doing our stuff. It’s crazy. Everybody sings the horn part. [Sings along] We sing every part of this song. Everybody sings it. So this is a guaguancó. You can feel the 6/8. This is the 4/4, but I can hear it: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

I hear it. This is really the ultimate polyrhythmic music.

It is. It is. And the thing with Celia that is really different from any other salsa female singer is that she’s not only a singer but she is a percussion player with her voice. She uses her voice harmonically and rhythmically at the same time, which is absolutely amazing. The way she plays the stuff. You listen to “Quimbara,” and try to sing it. Until you start singing that song, you don’t know how hard it is. It’s a real workout between your voice, the rhythm, and your breathing. And she does it all at the same time. This is the craziest song ever, and I love it. I love it. I love it! That’s why I did all the backing vocals. I wanted to make sure and everything is as I wanted it.

That’s all you?

Oh yeah, all me.

This album was obviously created out of the passion you felt after that Celebrate Brooklyn show. What’s your plan now for touring it?

Well, were going to tour it. We’re starting tomorrow at The Standard.

And what kind of the group are you using?

Oh, don’t be asking too many questions. Percussion, guitar, bass and drums. Just four people right now. We’re going to add all the rest later on.

Do you think you can get TonyAllen to do some gigs with you?

I do have a couple of TV engagements to do with him in France.

He gets around. He likes projects.

He likes projects. And when you see Tony play the drums, this guy’s not even sweating. Every drummer is working out and sweating. Tony’s like, “No sweat. Next.” One take. I’m like, “What is wrong with this guy?” He said to me, “I do one take, because I have it in me. You bring it. I play.” And then you see him sitting down at the drums, smiling, doing the break right on time, and coming back, and you’re like, “This is spooky. This is spooky as hell.” And he smiles and says, “Well, Angelique, you know who I am.” And I said, “I don’t know why I’m like this. You are bad. You’re really bad.”

He is just about the most relaxed drummer I’ve ever seen.

Oh yeah. He just sits on the rhythm and doesn’t go nowhere. He just supports everything and it’s like, “O.K., this is where the beat is. From there you can do whatever you want. I give you the beat and you do whatever you want."

I’ve been thinking back over your amazing career. This is your 15th album, right?

I don’t count anymore.

Whatever the number, there is such variety, all these different explorations. You set a very high bar for artists who would follow in your footsteps, just by being so brave and adventurous. But I’m curious, when the time comes to make another album of your own songs, when you’re touring and it’s not Celia or Talking Heads, what will be different? Will some of these songs stay in your live repertoire?

Probably. I don’t know. One thing that I like about life is that I can’t make plans because I don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow. It all depends, once again, on my inspiration. I can’t sit here and tell you what the next album is going to be. I can’t. It would be a pure lie. Because when you come back and we start talking, you’ll say, “But that’s not what you said last time.” Guess what? My inspiration does not take orders from me. I take orders from my inspiration. That’s how it works.

So for now, you can live in Celia World.

I’m going to live between Celia World and Remain in Light. For me, they are not separate from each other. For me it’s a bridge that I’m building between different musics. Philip Glass is not far from that world either. So for me, in my mind, it’s pretty clear that when it comes to music, there is no boundary for me. There will never be. Otherwise I would be doing the same thing over and over.

If there is one place on this earth that I love to be more than anything, it’s being on stage. And I want my stage to be always fun. If I get bored on stage, I’ll stop doing it. Because people won’t pay for it anymore. Why go on stage if you’re not willing to be there for people? To show your guts. There are some musicians that are technically very good, but they don’t have the courage to show their guts, because that’s when you are vulnerable. That’s when people want more. That’s when people give you more. But as soon as you stay on stage thinking that you are superior to your public, people will stop coming to see you. They don’t need that. You can check your ego at the door before you go on stage. We know everybody needs ego to go on stage. But that ego that you need on stage has to be in the service of what you have to say.

Well, you certainly deliver that every time.

I try.

Let me ask you about one more song, the opening track, “Cucala.”

[As the song plays, Angelique sings along.]

No one would ever guess that you don’t speak Spanish. Your pronunciation and flow are spot-on.

Yeah, but “Cucala.” The song is modern. She thinks she is a monument. She knows everything. She has nothing to learn from anybody, and she just likes to dance. And that’s what “Cucala” is about. She’s playing this idiot pretending she does not know how to dance. But she knows how to dance better than anybody. It’s just about the type of person who is witty, proud, and don’t want to take no crap from no guys. I’m me, and I do what I want to do.

Any other songs you want to tell us something special about?

I like “Sahara.” The imagination of the word, describing the desert. When the sun has set and the moon comes out, it’s like a turban around the earth. And it’s so true. If you’ve been in the desert, you know how the sand can be hot and everything is dry, and yet there’s life in the desert. And I like “Elegua.” I love all the songs. For me, it’s to tell a whole story about all that, Elegua, Yemaya, who is the equivalent of Hermes, the Greek messenger of the gods who sometimes messes up and create some havoc. It’s the same thing.

I like what you said about “Sahara.” Do you know if she ever visited the desert? Or was just something she conjured in her mind?

She probably saw some images and heard through the history that the slaves brought with them about the desert. You know, it’s an oral tradition. The memory of human beings is just something amazing. Especially if you live in a society where you are oppressed, where your culture doesn’t matter, where your humanity is denied, and everything that makes you travel is much more like a picture, like she depicts in the song.

So in choosing among so many of Celia’s songs, a big part of it was to tell the story of the orishas.

Absolutely, telling the story of our conductivity, both of us, Celia and myself. Because I too always have a fascination with the desert. I know the desert can be deadly. It’s an unfriendly place. And if you don’t know where you’re going, you can die quickly. But for me, the desert is life itself. You better make a plan before you get out in the desert. Know where the oases are. Know who your guide is in the desert. Guides for me are like role models. If you have the right one, you can travel the desert till the end of time.

I feel that. I remember going to Timbuktu and feeling the urge to join a camel party and just head out…

It’s like life. In life you have to have plans. You have purpose. You have to have dreams. And all of them might not come to fruition, but at least you don’t stay wondering what’s going to happen. You do that in the desert, you die. The desert gives you no second chance.

It’s the same for the ocean.

Yes. Same thing.

Well, we look forward to seeing this show live. You know, at South by Southwest, we presented a singer from Benin named Shirazee. He came up through the world of hip-hop, but his real ambition is to sing Afrobeats, to put the stamp of Benin on that rising style. I’m curious, have you ever been tempted to delve into the new Afrobeats sound?

I did. I just did a video with Yemi Alade. She took one of my songs, “Wombo Lombo.” You will hear it. The thing about this new music that is coming from Nigeria, it’s a mixture of 4/4 and 6/8.

In my experience, if you talk to Ivoirian musicians, they will say that the Nigerians stole this rhythm from their coupé decalé sound. And then if you talk to Congolese musicians, they will say that the Ivorians stole the sound from them, and then the Nigerians stole it from the Ivorians. I suppose there’s some truth to all of it, but it’s funny the way everyone wants to claim ownership.

It’s the same music everywhere. But it was really very clever for the young Nigerian artist to put those two things together and to mix it in a way that you can’t tear them apart. You hear the 4/4 and 6/8, but it’s on the beat all the time. It’s amazing.

That was a real turning point when producers started doing that rather than using the borrowed hip-hop and dancehall rhythms.

Exactly.

It has been interesting to watch this music evolve.

And now everybody wants to do it.

Right. Before people used to say, “Oh, you’re just imitating the Americans.” But it’s not imitating the Americans anymore.

No. It’s not imitating the Americans At all. No. The Internet has allowed us to own something that has always been ours before. Somebody came and took it away. And it’s the blend of rhythms. You come and take it and make something new and never give credit for it. But that’s the thing today. You can’t take anything from Africa anymore without somebody saying, “Hey, buddy. This is where I come from.”

It’s all out there now.

Yes it is.

Thanks so much for talking with us again, Angelique. The album is fantastic, and we really look forward to seeing it live.

Thank you.

Related Audio Programs