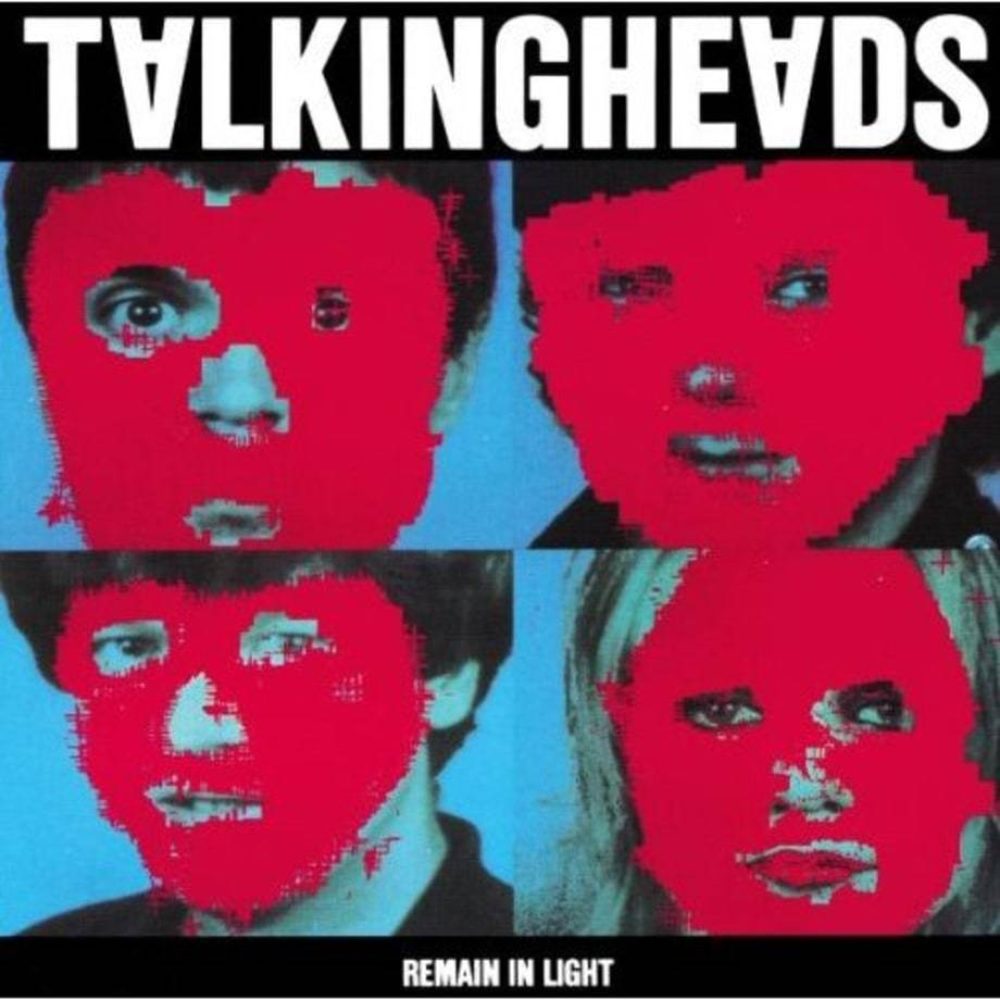

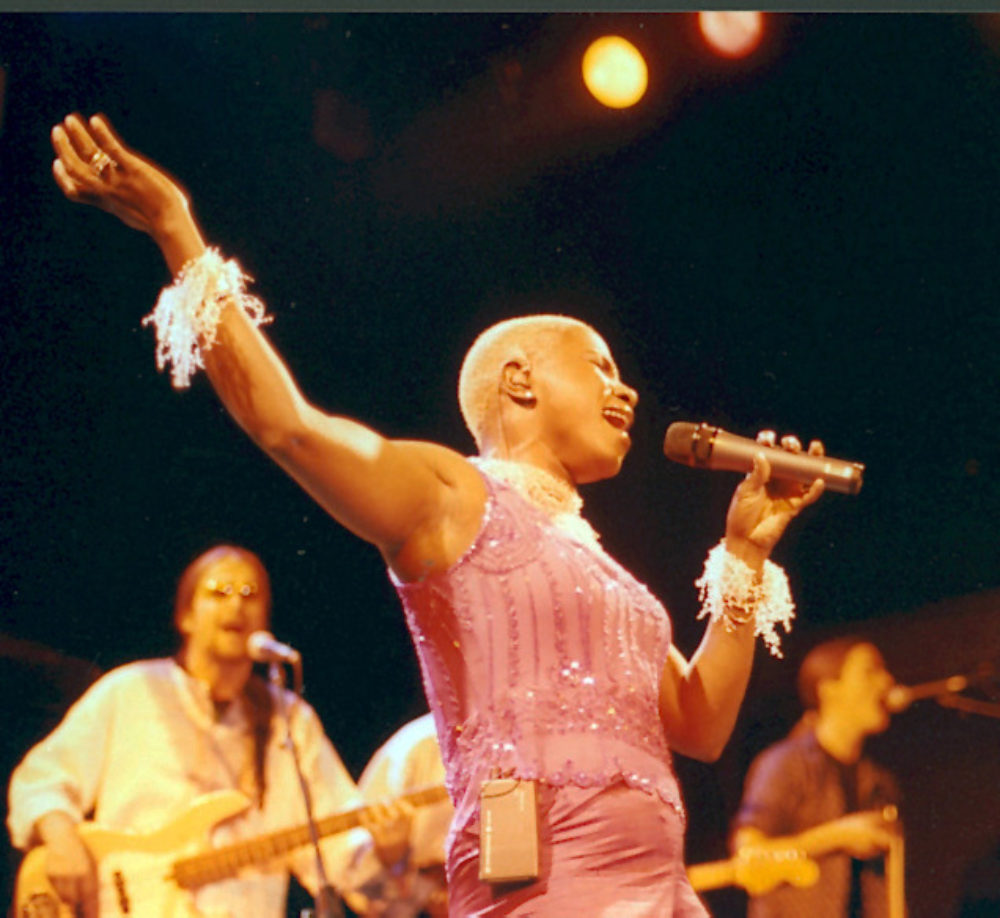

Angelique Kidjo is one of those artists who need no introduction. The adventurism and diversity in her catalog of recordings is unmatched by any other African musician today. Her latest adventure is a remake of the classic Talking Heads album Remain in Light. Banning Eyre visited Angelique at her Brooklyn home to talk about the album. Here’s their conversation.

Great to talk to you again, Angelique. How’s everything been?

Good! Can’t complain!

So this Remain in Light project is fascinating. I listened to the original and yours back-to-back yesterday, which is a revealing experience. Took me back, because I was a person just out of college when that record came out.

Wow.

Yes, Talking Heads were a big deal in 1980. Tell me your first experience with this record specifically.

My first encounter with the Remain in Light album was something I never thought was gonna end up in an album of mine. When I moved to Paris in 1983, I was a music junkie because from the moment the military, the communism regime, arrived, there was no music on the radio pretty much. Just like propaganda music day in, day out. And the radio that I grew up relying on to play new songs that come from all over the world became suddenly mute. It was very difficult for somebody like me that always spent my days listening to music. I come back from school and the first thing I do is listen to music. Even in your home you couldn’t do that anymore; you didn’t have the right to do that.

Even in your home? You were forbidden or just intimidated?

That’s it. Whenever talk, you talk about the revolution, you sing about the revolution. You can listen to other music, but you have to put the headphones on, and make sure nobody is seeing you listening to something else.

Really?

Oh, it has been very hard… I mean, [Laughs bitterly] Americans never feel that, and you can basically call your mom Mom, your dad Dad, your friend, your family, everybody you see, you have to call them “Comrade.” I’m like…whoa, this is something else… So when I arrived in Paris, I started really consuming music at a rapid pace—just like, everything. I’m listening to so much music. I don’t care where it comes from. I don’t care if you call it classic, hip-hop, whatever you call the music, I’m listening to it. So at a party, somebody played that song “Once in A Lifetime,” and I’m like, this is an African song. African, and I shouldn’t have said anything, but I’m like, “Oh, you guys.” But to them I’m not sophisticated enough to do this kind of music. Everything Africa is just jibberish to them.

And I’m like, O.K. When I arrived in France, the first year was the hardest one for me. My brother used to tell me, “You gonna cry a lot. And then you gonna lose all the warmth that we have in Africa, greeting people, talking to people, people don’t do that here.” And you see it in newcomers. If I see any African person with a big smile, nice to everybody I’m like, you have another year…and then you’ll be dead. I have fought against that a lot. Because I didn’t want to lose who I was, but you are forced, by coming, by attitude, the way people perceive you, the way people don’t wanna deal with you, basically, because first of all, they don’t know anything about the culture. Secondly, for them, Africa is just a place where we are all…we hanging out with monkeys in the trees, and we don’t have intelligence, we don’t, we can’t make choices for ourselves…and that is the narrative that comes out of slavery and colonization.

When it comes to music, it’s your opinion, and mine is mine. But forward to today, that song stayed with me because the comment was really pretty rough on me. It’s the same thing as when I heard “Voodoo Child.” It was the same thing when I hear Ravel’s “Bolero.” All those songs, that lead to a moment where I faced human stupidity, [Laughs] and it’s just, like, crazy. And there are more. I can write a book about them, but it just doesn’t matter. I turned that always into music to bring knowledge and awareness on the fact that we are one, basically. So I decided to do this album because…I don’t know…it just woke something up in me. I didn’t know the lyrics at the time because I came from a French-speaking country; I didn’t speak English. All the English songs I listened to when I was growing up, I made up my own words. I speak pidgin from Nigeria because my mom is from Nigeria, but the English of the British, of the American, I didn’t know it. So for me, that “Once in A Lifetime” was like…[Hums melody] all the time, so I’m like, O.K. So we reached out. Jean, my manager found [David Byrne] and he said you should do that. We spoke to Danny Kapilian, and that’s when they were telling me who wrote that song, and where it comes from. I’m like, O.K., let’s find the album. So we found the album, we listened to it.

When was this?

Two or three years ago.

So you hadn’t been listening to that album over the years.

I didn’t even know who was the Talking Heads! Nor David Byrne when I was in Africa. I didn’t know anything about them, because of political situation in Africa. David Byrne, and all the music never made it to Benin. So when I arrived in France, I discovered the Talking Heads, in the '80s.

Sure. But this is years later.

I met David Byrne when I came here. He was the first artist that really came to my show when I was playing at SOBs in the ‘90s. And for me, at that time, I connect him with his long hair.

Yeah.

Another time I saw him, I’m like, I know this face; they said this is David Byrne. I’m like no, he had long hair; they said, no, he cut his hair. O.K. So for me, since I’m in America of course I know the Talking Heads and David Byrne, but when I started doing this album I discovered the way they took risks, because doing music is about also challenging yourself all the time. And some people are afraid when they find a niche of something that works, they don’t wanna get out of there. And that band, for the time they existed, every album was just an experience.

True.

Every album was moving boundaries, and for me, it works perfectly, because that’s the type of artist that I am. So when we started to work on it, it was obvious that I would have to listen to the album differently. Because what I knew in the '80s was not the lyrics; it was the melody of the chorus of “Once in A Lifetime.” So now I really delved, I mean I jumped in it, I dove into it. And it was an interesting journey.

Have you ever talked to David about what was in his head when he was arranging the song?

[Laughs] Nooo, I didn’t ask him, I didn’t ask him. I asked the permission to all of them, and I get the blessing before I start on this project, and since this album has been recorded, I’ve done three shows: one in Houston, one in Berkeley, and one in L.A. and I have Jerry Harrison on the guitar and keyboard with us, and it has been absolutely amazing. I mean it’s such a different thing, but yet the same kind of experience of having my band members as it is to have Jerry with me. Because he fits right in, I mean he just got the guitar right back where it started and it fits on everything we do. Even though the rhythm has changed, he just take the guitar and bam! I’m like yeah, that’s what I’m talking about.

It was such an interesting choice to do the whole album. How did that come about? I mean you could have just covered that song and maybe some other songs. How did that particular decision come about?

Listening to the album, for me, one song after the other was telling a story. It was not an album that you can just take the song. For me, this was the tapestry. It was all done in a way that perhaps because of the looping that was in there that reminded me of drums, the constant pattern of drums, that induced us to come into joyful prayers in Africa. Perhaps that’s what I was feeling, and also, as I was listening I realized that I was listening to Fela, they were reading books by [John Miller] Chernoff on West African music. It is interesting for me that young Americans—I mean at that time they were young—became interested in culture that is far away geographically, maybe not humanly. But also not just to copy it, to get the inspiration and understand [Claps] the power of that trance, and put it into a loop and work on it. So as I was listening to the first song, the second, the third, through all of them I was seeing that it’s like a thread you are unfolding, and it’s all the same color, all the way through. So for me it became important to do it like that.

Every song comes with a strong message, and I realized also that the album was in the Reagan era, and the anxiety you feel by listening to it comes from the moment also, and that David, when they were preparing the album, he was watching the preachers on TV, doing preaching, while in New York, he was witnessing the war on drugs of Reagan and so many black people put into jail. And you know people always think that there is one idea about America, that American people are the same. Everywhere I go in the world: “The Americans are like this.” It drives me crazy when people say that. I say, no, you can’t just put a whole country in a basket and throw it in the water, saying everybody’s the same. I refuse. So listen to the Talking Heads album in this time, and to me it meant courage. It was always said: “You can’t do that album. There’s no meaning to the words. And it’s absurd.” Oh no. It’s not. It’s pure poetry, it’s done in a way to grab your attention, to capture the time you’re living in. And every single song has a political angle for me.

That’s amazing. First of all, I love the idea of respecting the album as an overall work, because that idea is kind of disappearing these days. We grew up with it, but nowadays with YouTube videos and singles and downloads and everything, the idea of an album that has a wholeness to it is kind of fading. I’m interested in the political angle too. There are parts of both the original album and yours where we hear spoken words, but you’re speaking in Fon, an African language. Tell me about those sections. Are you basically translating, or adding your own words?

O.K., first “Houses in Motion.” “Houses in Motion” is the one where I felt that I had to speak. I mean, I listened to it go to bed and sleep, and when I listened to lyrics of the Talking Heads, what comes to me is the despair of people after the crisis of 2008. During that time I toured a lot on the West Coast, and I had a friend who was living there and she was telling me that she lost everything after that, even her apartment. This was something that touched people very close to me. Then she said, “Let me show you something,” and she drove me by the bridges in San Francisco. We saw kids that have to go use fountain to wash their face before they go to school. Their mother, everybody had to go there. And I’m like, even in Africa, it’s not this hard. And there’s no net to save people. We have a political system that only functions for a fraction of people in this country, where the rest of the population in America has to fight to survive.

This is not capitalism anymore, for me. It’s totalitarian regime, and it breaks my heart. So “Houses in Motion” is a dream that you have about somebody that you know, and then you wake up and you’re in the same situation, with the same anxiety, and then you say to yourself, “Well, here I wake up without shoes, without a home, without clothes, in the cold. But deep down in my soul, I know that I’m gonna be O.K., that if I put myself back to work, my life can be better. But on the other hand, here is my friend that I’m seeing digging a hole in the house that she’s gonna lose, but before she loses the house she wants to break the house down. And I say, “Why are you digging a hole?” And she answers, “I have to do it. If it have to take me the rest of my life to dig this hole, and to dig this house to the ground, that’s what I’m gonna do.” And I say, “If you’re just ready to die for this house—then what are you? I mean, don’t you have anything? Can I help? Can we talk about this?” And her reply to my help was, “Who is born to this world with his hands filled with gold? No one. We were born all naked to this world, and we’re gonna leave naked.” So we don’t bring anything, and we create fear. We build fear in our home, in our heart, and everywhere, and we know very well that the day we die, none of this will count. That’s what I’m saying in this song.

That’s a strong message. Thomas Mapfumo has a song with a message like that. It’s kind of his way of criticizing greedy, power-hungry people. When they die, none of that will matter. What about “Seen and Not Seen?” You have added a vocal section to the beginning of this one.

Well, “Seen and Not Seen”… The thing that was really amazing doing this album was, when I was preparing my last album, Eve, we went to Kenya where we recorded women, and we went to Benin and recorded the women in Benin. And as I was listening to the Talking Heads album, it became obvious that the voices of those women, the countless songs that they sung to me, I have to go listen to them and see how they can be a kind of call-and-response to this album. And I listened to the song “Seen and Not Seen” and I thought, it’s obvious that this song would fit. This is something I never did in the past. So I’m like, “I’m just gonna follow wherever these songs lead me.” No pressure, and if there is none, I’m just gonna write it, because it’s gonna be in my head. So, that’s what’s happening in “Seen and Not Seen,” because in all the songs that I was listening to, I couldn’t find it. But what came to my mind with “Seen and Not Seen” was this. Three years ago or so, I received this prize called Ashke in Benin. This is an organization of women entrepreneurs in the market, businesswomen in Benin that give that award—I was first recipient of it—to women who participate in the economy with an awareness of women’s issues in the world. When I arrived to the awards ceremony, I didn’t expect so many people. There were at least 450 people. So I sat down there, and I’m like, most of those people have seen me grow up. I might not remember all of them, but it’s an obligation that I felt, that they chose me and I have to thank everybody.

So I went around the room and went to every table and I greet all 450 people. And at one point I arrived at the table and an elderly lady said to me, “Come sit on my lap.” And I said “I can’t do that.” She said, “I carry heavier people than you. Come sit down. I have something to tell you.” So I sat on her lap and she said, “We watched you grow in this country, we watched you grow in the world, and every time you appear on TV, you make us proud. You never tried to change who you are. You never tried to bleach your skin. But here, do you see your sisters? We’re having so many skin cancers because they are bleaching left and right. You gotta write a song about this. It’s dangerous for their health and it’s dangerous for the economy. Because there are women dying, what are we gonna do?”

And I’m like, well, but this is a private choice, I cannot just start talking about the choices they made for themselves. And she said, “Yes, but bring awareness somehow to this issue.” So basically the lyrics I added to “Seen and Not Seen” are about changing your face, your appearance, to fit your personality and not the other way around. I am saying, “Stop torturing your body. Nature gave you a beauty. You might not see it but that beauty fits you. Love yourself. Love yourself.”

Hmm. That fits with the title too. Coming back to the music, you really bring whole new richness to these songs with all the brass and percussion. I listened back to the originals, which I remember so well, and I love them, but they seemed kind of naked to me after listening to what you have done. I hear what you’re saying about the loops, and how they bring an African sensibility to songs. But by adding all this African percussion, you create yet another of those wonderful conversations between Africa and the Americas—an idea that runs through so much of your work.

Absolutely. That’s why we started with “Once in a Lifetime.” That was the first song we start working on with Jeff Bhasker. I met Jeff a couple of years ago in London when I was receiving another award for my activism, and he was the musical director. But I was the honoree and at the same time I was singing among Blood Orange, Florence and the Machine, and all those big artists. So I had a percussionist, I mean I only brought Dominique, my guitar player, and I know a Senegalese percussionist I had worked with in London, and he came in and we did “Tumba.” I always have a call and response with the percussion on that song, and Jeff was fascinated by that. And so we were going to do “Once in A Lifetime.” Then he said, O.K., this is an iconic album, and he got hooked so we did the whole album. At the start, he said, “Bring your percussion player.” My percussion player lives in L.A. He’s from Senegal, Magatte. And then he said, “We gonna do call and response to start this song.” That’s why you have: [Clap] You may find yourself… [Clap]…

Then from that point on, every song was built on the percussion. I already had some percussion from Benin in the mix, and we added Magatte to it. The drummer has to follow and that day, Charles Haynes, a friend of Jeff’s, came in and played drums. Magatte was there, and it was like call-and-response drum and percussion, but in a way that just locked the song down.

Mmm.

So the rest, I mean the horns for the whole album was done by Antibalas, and it is an amazing thing to see when you’re doing a project and everything you touch feels right. This album has brought me so many people that I never thought would be there. Pino Paladino was in town, I called him, he came in and played the bass on most of the songs. Only two songs were played by the bass player I work with, Rody Cereyon. Rody Cereyon also works with Tony Allen, so for us, we said we need the inventor of Afrobeat. We need Tony Allen. I mean, nobody else. And he played “Crosseyed and Painless” and “Houses in Motion.”

Nice.

It was crazy. He walked into the studio and sat at the drums, and you just say [Laughs], “This guy ain’t playing no drums. He’s just having fun. He’s so relaxed and smiling.” I look at him, I’m like, “I wish all the drummers could play like that! He just owns it. How can he be carrying all this stuff with so much elegance and flawless and easiness?” And that’s how we did the album. Pretty much everything just fell in organically.

So you say Jeff was originally just gonna do just that one song.

Because he was like, “Oh, man, this is scary to touch.” And then after he started watching video of the live shows, he said, “Oh, there’s so much to this.” So most of the keyboards were played by Jeff. He got hooked. The only thing he didn’t touch is my voice. The only song that I re-sang was “Born Under Punches,” because he wanted a microphone that would make my voice a little bit warmer and more present, so we put it in and I did it. Right there. But all the voices that I’ve recorded here, the demo voices, we kept them exactly the same.

There are some African melodies that you have added in places. I imagine that these are the vocal melodies that you’ve been talking about, that have been coming from Benin traditionally. There are places where I think are the kind of melodies we hear in Gangbé Bass Brand.

Well, those are pretty much the traditional songs that the women in the Eve project sung. So I took some of it and harmonized it, and I sang it, because it’s what the song was asking for. And also all of those songs that I sung have a deep meaning that is linked to the original song. Like on “Born Under Punches,” I’m talking about corruption. Corruption is a crime against humanity and since we have been on this earth we create corruption to take money from the poorest, to take money from the children, to take money from society that needs it to have a better society. We worship money more than we worship God or anything. For me, human life is out of bounds. There’s no price to it, but even that we touch. It’s the original sin of human beings on this planet. That’s why the song in my language says, “Don’t play with fire, Don’t start with fire. You cannot stop. Fire feeds you. Fire keeps you alive. But yet, fire has rules, and if you don’t deal well with fire, fire gonna come and wipe you out. You gonna burn everything to ashes.”

So you’ve filled out these iconic songs with African wisdom.

Yeah. There are a lot of proverbs there. Absolutely.

I’m curious. Has David heard this?

I think David has heard it. Before we did the show at Carnegie Hall, he wrote on his blog, “I had nothing to do with this. I didn’t ask Angelique to do it.” And then he said, “Well, I wish I could have done it like that, but Angelique did it.” [Laughs]

I bet he did feel that way. I don’t see how he couldn’t love it.

[Laughs] It’s amazing that an album written when I was experiencing oppression, that gave me a sense of longing at that party in Paris, where I felt like “Man, I would give anything to be back home safe, yet if I hang on here, I might be able to make something out of my life, instead of ending up in jail.” One song. And that song was written miles away from where I was growing up and going through that. For me, people play with fire too much. Our freedom is not set in stone, and we can’t play with it. I don’t care if you’re angry. I don’t care what you think about. If you are selfish enough to endanger this world by putting to power people that have no sense of community, of what is right and wrong, what is true and not true, and preserving the future of a country, you only have yourself to blame, but everybody’s a victim. Everybody.

For me, music has been always been the way my ancestors taught me to be the witness of my time. If you choose to be quiet, it’s your choice, then after you can talk. If you choose to talk, talk with courage, stand behind your word, and empower people to do something.

The moment in which this album is coming out is an interesting one, not just politically but in terms of culture. I was thinking about Afrofuturism and the recent Black Panther phenomenon, this reconceptualization of Africa leapfrogging all of the agonies of the recent centuries into something new and better. And I’m sure you’ve seen Black Panther, you see that kind of aspirational, visionary thing that’s so powerful in that movie. And I feel some of that on this record. Am I crazy?

No you’re not crazy! Afrofuturism has always been part of my work. Since the beginning, I got out of Benin because I don’t see people as a color. I never did. It never occurred to me to say, “This person is white.” I don’t care! That person might be white! That person has a father and a mother like I do! So if I don’t want someone to do something done wrong to me, why should I do that to anybody else? And in my music, I express that all the time. You know my career very well. Everything I’ve done is to put Africa at the center of everything, for people to realize that we are not that far apart. So sitting down on your couch, and bitching, and spitting on Africa is on yourself, because we are all Africans.

Black Panther came and I went to see it. It’s a very good movie, it’s a great movie, it’s very timely. Because the resources we have in Africa become our curse. When the Westerner set foot on our shores, those resources became our worst nightmare. And wherever Westerners have been, the tendency has always been, “We’ll kill if we have to, we’ll destroy everything, and we will put what we want there.” It’s not sustainable, and in Wakanda, instead of opening up to give away their resources, they wanna keep it and develop themselves and perhaps open up to help the world, but only if they’re still in control of their wealth. That is the problem we have in Africa. We are not in control of our wealth. Cobalt is the new stuff that is being taken out of the Democratic Republic of Congo. That’s why on “Born Under Punches,” the first word you hear is “Congo,” because that’s the country where every company in the world is making billions of dollars.

You’ll never get any American company coming back to sit down at CNN or MTV doing an interview, saying how much money they make in Africa. For me Afrofuturism is the way to tell people, “You’ve been having it the good way for so long at the cost of our lives, at the cost of our dreams to be better.” They have been keeping in place our corrupt leaders so they can’t even do something for themselves and their country. That cannot last anymore, because from within your country, there gonna be revolution. Not us. We never been violent enough for revolution. We’ll never be, and our kindness is turned against us all the time. We welcome people, we give them everything, you know. You go to Africa, you go to a poor village, if they have one bowl of rice, they will give it to you and they will go hungry, and you come here you don’t see that kind of generosity, ever. And it’s one way, all the time.

So things are shifting, and the only thing I want is the shift has to happen smoothly. Not in bloodshed. I don’t believe in violence to create anything positive; I don’t believe in hate to create anything positive. We had the second World War and here we are again, having pro-Nazi people in the street, and those young kids—it’s out of ignorance that they’re doing that. Because if they knew really what happened, I don’t think, out of your goodness and your smartness, you would want to embrace this kind of rhetoric. So for me Afrofuturism is to give people also the sense of belonging, the sense of community.

Amen.

And we don’t have that kind of community in America, in any rich country. It has been done on purpose to individualize everyone in order to profit from it. Our survival, our life on this planet depends on how quickly we see that what is good for us is good for others, and if we don’t do that, I’m telling you, if Mother Nature starts feeling us as nuisance, we can stop nothing. The rich can go to Mars. They’re gonna die there, because there’s nothing there. The only planet where you can live is here. This is the Mother Earth, where you gonna live. Every message that come from nature is urging us to get back to the core value of a humanity, and we have been deaf to it.

Thank you so much, Angelique. I just want to end by saying that artistically this is an interesting moment in African music because, as we’ve discussed before, a new generation is coming in…

Yeah.

With Afrobeats and all these new sounds, there’s a sense that young people are searching for something, trying to find a new way. But I think a lot of us feel that a lot is being lost in the process. There’s a lot of denial, a lot of separation from the kind of culture that we at Afropop are always looking in young artists, emerging artists. But you are such a model for these artists, a model of someone who can carry all that tradition and all that awareness with you and still be totally free to do something as completely out of the mold as this record. That sets such a good example for young artists, and I hope many of them pay attention and are willing to break the mold as you have.

They have to, because it’s for the survival of our own culture. Our culture is so rich that even for us it’s a challenge. How do we embrace the challenge and open to the world, and give to the world what we have in a different way. Rock ‘n’ roll is not something that African people consume. It has been like that for as long as I can recall. So for me, bringing rock ‘n’ roll back with Afrobeat, it’s a message I’m sending to the next generation, that every music out there, you can trace it back to your home town, to your doorstep. And you can take it, do it with what you’ve got, turn the narrative in a different way. Don’t just be consuming what comes from America, thinking that what comes from America is better than what you have.

Take what comes from America and Africanize it. Take Beyonce, take Kanye West, every single artist in this world. Just bring it back to Africa and nail it down with drums. And the people that wrote it, they’re gonna go, “What the hell? We didn’t do nothing, because we took it from Africa.” Acknowledge it. Be proud of that root in your music. An African has to be really proud of his or her own culture, and that’s where it becomes tricky, but I think there are a lot of young artists in Africa today who know that, and they are finding ways to do this. If by doing this album, I open a little tiny bitty bit of a space in that window for them to see the possibilities, the endless possibilities of what we can do out of Africa with music, I die in peace.

That’s beautiful. Thanks so much, Angelique

[Laughs] Thanks.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles