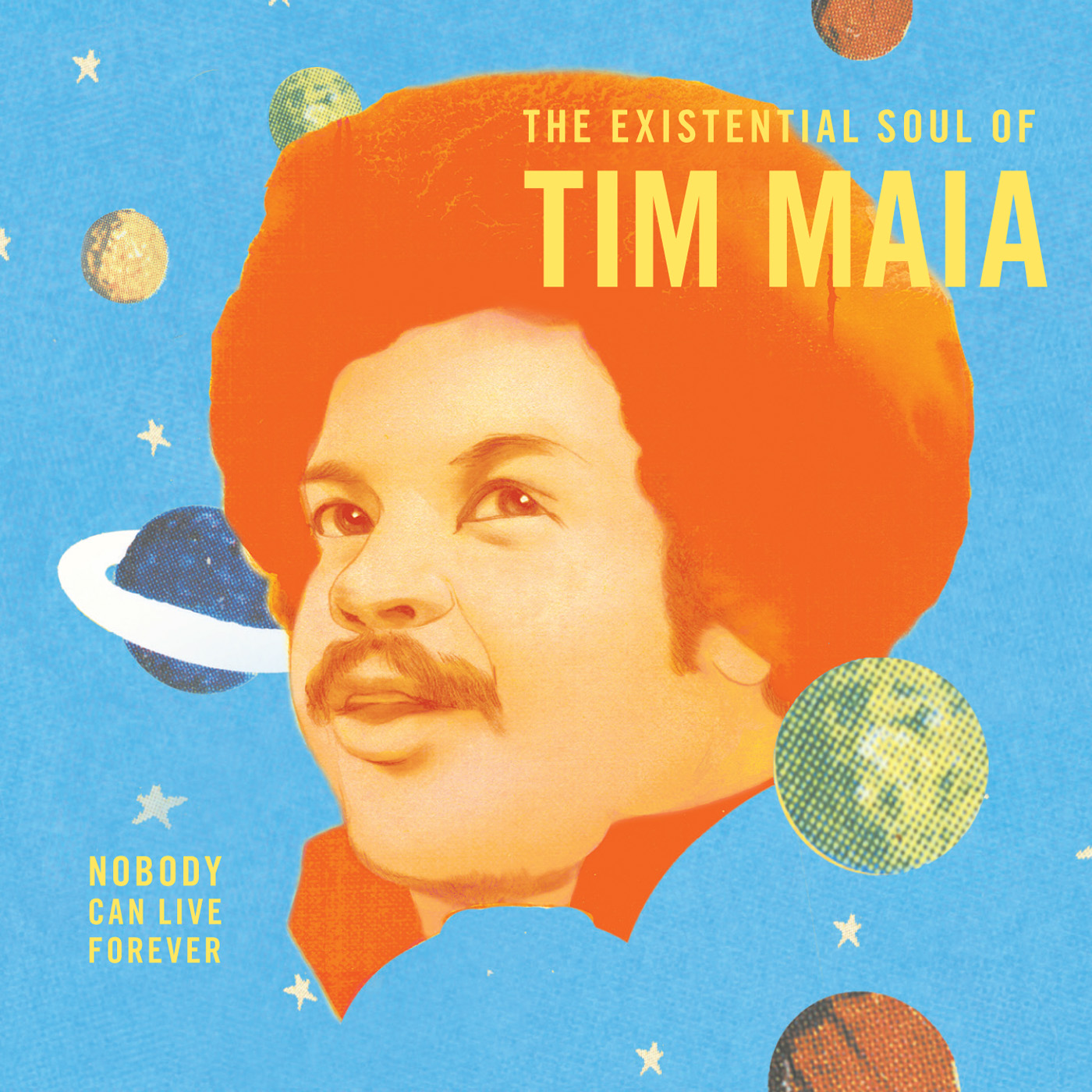

At the height of his powers in the mid-1970s, Brazilian soul-funk pioneer Tim Maia left his label and his fabled hedonism behind and joined the cult of Rational Culture. He didn't stop making music during this period; he just made it sober and sold the results door to door. And the albums he recorded during this era—the two that have sneaked into the present—are still really, really good, even if the lyrics are constantly needling you to read some weird book about humanity's origins from UFOs and microbes.

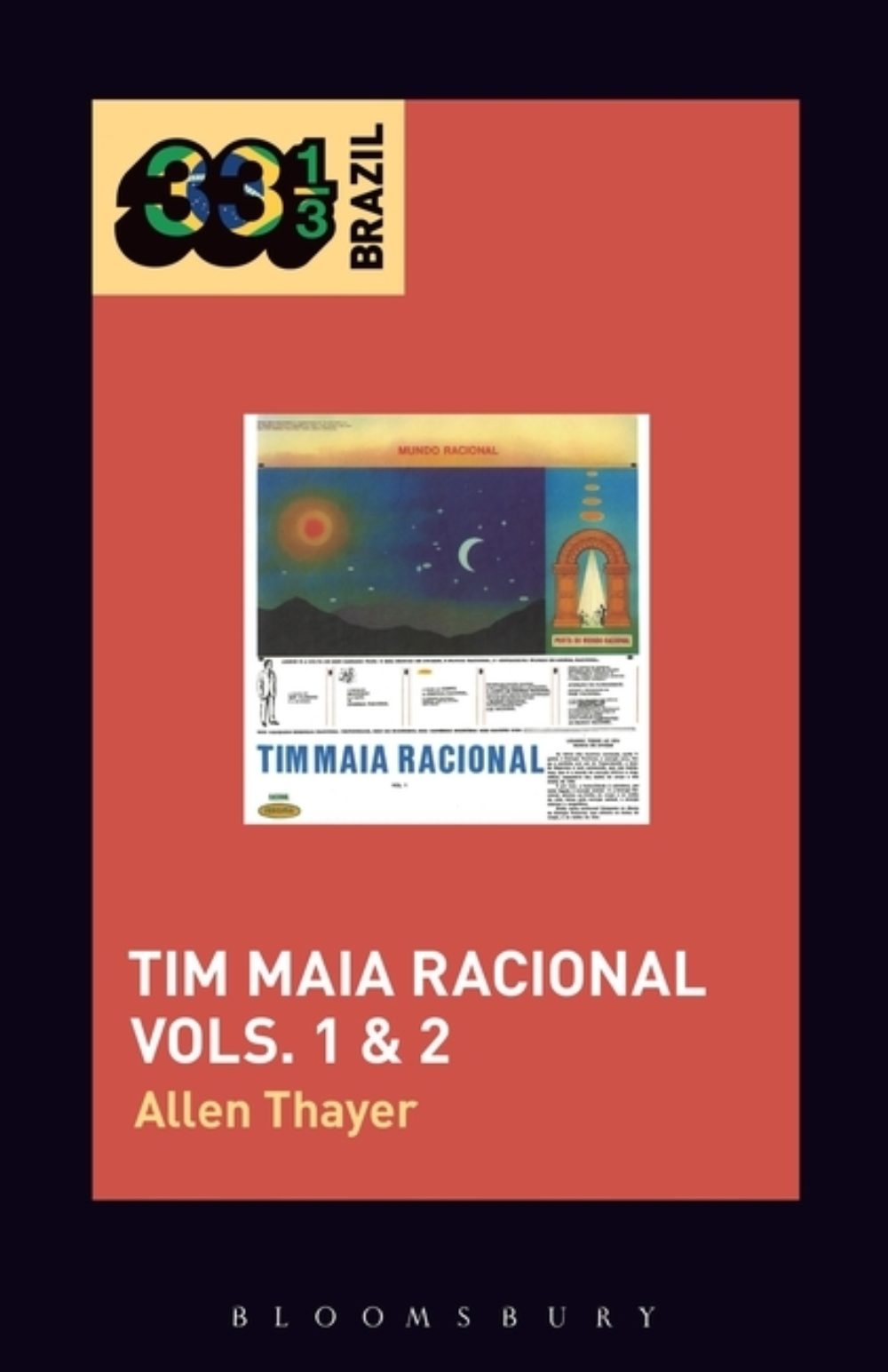

Allen Thayer, who has written for the crate-digging magazine Wax Poetics, put Maia's Rational Culture albums in context in a new book, Tim Maia Racional Vols. 1 & 2, part of the "33 1/3" series's new Brazil-centric imprint. The series is already a wonder, and I was pretty much beside myself when I ripped open the envelope it arrived in and realized there was going to be a whole series devoted to albums whose stories remain undertold and hard to find, at least in English.

And that context is especially valuable in the U.S. where a new generation of listeners, interested in funk from around the world, is coming to the music via streaming services, without even liner notes to guide them. I came across Maia's music via Luaka Bop's compilations, which draw heavily from the Racional era, but I came across them via Spotify, so I just sort of naively assumed that Maia was an unheralded genius in his homeland—until I saw a collapsed Rio bike path had been named for him. Turns out, Tim Maia was a radio mainstay. Which makes his dalliance with Rational Culture even more fascinating.

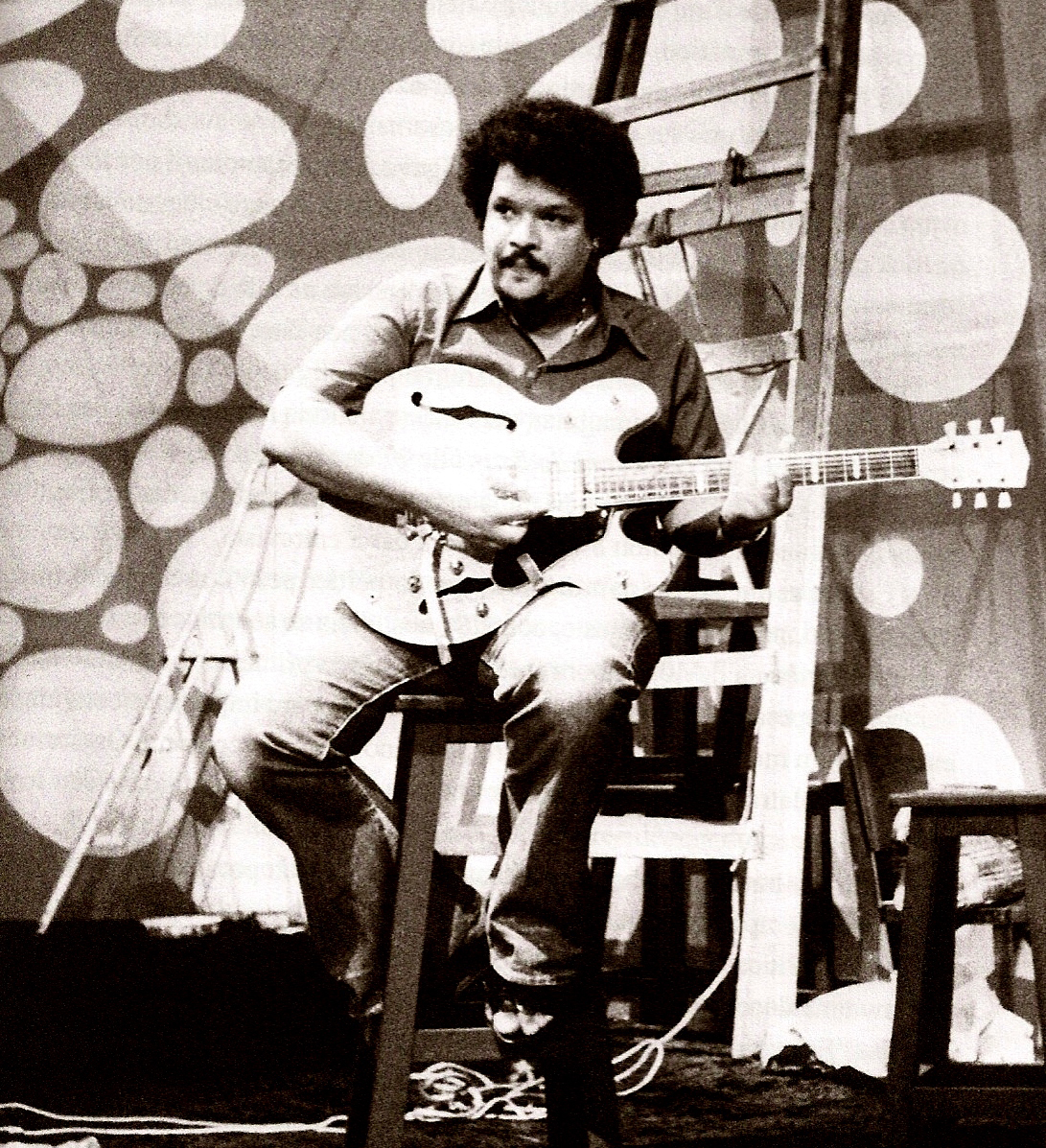

Born in 1942 as the 18th out of 19 children, Maia grew up to be something of a malandro—a sort of favela wise guy and scamp. He loved food and he loved music, and while being black and overweight didn't make his rise to stardom any easier, his natural talent coupled with nigh-obsessive hard work made it happen. During a foray in the United States in the '60s, Maia fell in love with American soul and r&b. As his music and the man himself made clear in interviews later in life, he detected a shared African origin behind it and Brazilian music, was one of the first to start the conversation between the two when he returned to Brazil (after he, uh, got out of a quick stint in jail. As a thief, Maia was less than genius).

Thayer relays Maia's quick, hedonistic rise that culminates in Maia having a Copacabana apartment and a practice compound where he and his chosen band could smoke copious amounts of pot and jam day and night. As chill as that sounds, Maia deserves to be mentioned with James Brown, not just in terms of funkiness, but in terms of being a very demanding bandleader, berating musicians who missed notes.

But the drinking and marijuana—and the meat-eating and wearing colors other than white—came to a stop in the mid-'70s when Maia encountered the Rational Culture Movement led by Manoel Jacinto Coelho.

At just 31, Coelho wrote the manifesto that was the holy text and most of the practice of the Rational Culture Movement, titled Universe of Disenchantment. Coelho had been a medium in the Afro-Brazilian practice of umbanda, and claimed to just be transcribing the message from the Rational Superior when he put out Universe in the 1930s.

As the story goes, after a particularly bad performance on TV on acid, Maia was taking a break by only doing nice, organic mescaline. While waiting for bandmate to get out of the shower, Maia came across a copy of Universe lying around in the bandmate's apartment and started to read it. Without going too much into it, Maia was already into UFOs; and Universe states that human origins are from outer space, and our purpose is to reconnect with the rational energy of the universe, which is done through reading and re-reading the book over and over. Coelho sounds like a cult leader from central casting—six-foot six inches tall, dressing all in white and charismatic enough to win over Maia when they met.

This dramatic religious conversion was pretty jarring, but Maia's bandmates seemed pretty much on-board. As his loyal lead guitarist told Thayer, no one was forced to quit drugs; it was a self-evidently good idea. Wearing all white? O.K., sure. Rewriting the lyrics to the songs they were working on in the mid-'70s? Maia's label, Polydor, was less than O.K. with that. So Maia took his tapes and left, self-releasing three Rational Culture-centric records from late 1974 through 1976.

It's not a long period of time, but it's still head-scratching, like if Bob Dylan left Columbia to make Scientology records at the height of his '60s powers. (Actually, given that Dylan disappeared at the end of the '60s, popped out John Wesley Harding and had a religious phase, it's much like a lot of incomprehensible Bob Dylan decisions, just way more commercially self-destructive.) Maia pumped a ton of money into Rational Culture's coffers, left his label, and alienated his professional connections as well as his band. Yet, as Thayer points out in his track-by-track readings of the Racional Culture records, the music is fantastic. Living cleanly was great for Maia's voice, and it's no wonder that the Luaka Bop compilation draws heavily from this period.

Thayer does an admirable job finding and interviewing band members from this era, but without Maia, who died in 1998, the center still feels murky. We don't exactly learn why Maia dove so hard into Rational Culture and we know even less about why he left and resumed his rock 'n' roll lifestyle and also finished the '70s with a disco-fueled return to relevance. His own liner notes on his first, post-Rational culture album in 1977 are also less than illuminating:

What I learned is that I learned that I didn't learn anything. Lots of things don't exist that they say exist. What exists is right here and we can't see.

For me the most important people are the children (because they represent the future). However, if misguided they will be lost, like us, in the middle of lies.

Thayer does an admirable job of describing Rational Culture both relatably—Brazil's not the only place in the '70s where outre religions catch on—and specifically to its context—it was under an oppressive military regime at the time. The Rational Culture era of Tim Maia's career still seems beyond reach, just as the limited-run records from this era remain out of the reach of collectors. Thayer set out to thwart the easy narrative of "Tim Maia joined a wild cult and made great songs that you just have to ignore the bonkers lyrics on." But even now that I know why Maia made a 12-minute funk epic that implores me to read and re-read "the book," that approach still appeals to me.

Related Audio Programs