People talk about being stopped in their tracks by music, but living above a tape stall in Dakar, Senegal, Matthew Lavoie was interrupted in the middle of breakfast. A slick guitar break he heard that morning in 1996 started him on what turned out to be a two decade-long journey to learn just who the Orchestre Kiam was. It led to a full-on oral history of a band that was once well known throughout West Africa and from Nigeria to Kenya, but is now mostly forgotten in their home of Kinshasa.

Lavoie has posted his thorough oral history of the group on his latest blog, Wallahi le Zein!, as well as a link to much of their (otherwise unavailable) discography. When you hear Kiam play, you can see why Lavoie had to go downstairs and check it out. Their fleet guitar lines melodically intertwine and flicker apart, creating a roiling sea for the vocals to skip across and open up into harmonies. It wouldn’t be all that strange to hear they were on the tier of fame just below soukous royalty like Franco and TPOK Jazz, but it is sort of strange to google them and realize that so little about them has made it to the Internet--until now, that is.

A former writer, producer and presenter of Voice of America’s Music Time in Africa, Lavoie has been blogging about African music old and new for over a decade, first for VOA under the title “African Music Treasures,” and now independently. No matter where they appear, these are some of the finest blog posts you’ll see, researched so exhaustively that his post on the Somali record label Light & Sound, and his post on Mauritanian guitar player Hammadi ould Nana, both resulted in commercially released compilations.

His work on Kiam is no less impressive. After talking to 21 musicians in Europe, Kinshasa and elsewhere, Lavoie has put together a stunning history of the band. You’re a handful of clicks away from being an expert on a group that became one of Kinshasa’s overlooked gems. It’s easy to imagine the oral history appearing in some form or another on the inside of a beautiful, gatefold two-LP compilation released by, say, Analog Africa, but Lavoie doesn’t think that’s going to happen.

“The research was an end in itself,” Lavoie told Afropop in an email. “I would love for the band’s music to be recognized through an official reissue. I am, however, skeptical that this is possible, both due to market interest and the complications seemingly inherent in all reissues of Congolese music.”

Those complications hint at a wider truth: To understand the story of Orchestre Kiam is to wade into one of the most interesting and artistically vital scenes in music history, but one also rife with dubious contracts and legal knots. As the ‘60s dawned over the continent, music from the newly independent Belgian Congo (soon to be renamed the Republic of Zaire) and its neighbor Congo-Brazzaville emerged as a post-colonial musical powerhouse. And as with any boom town, businessmen showed up in Kinshasa—and not all of them were on the up and up. Band members often received salaries, but rarely owned the rights to the music they made, which has implications that carry to today.

“Generation after generation of yesterday’s hit makers are today struggling in difficult circumstances,” Lavoie said. “While Orchestre Kiam marked a generation of listeners throughout Africa, and their original recordings today generate income for Western collectors (with prices rising), these musicians haven’t earned a nickel for their efforts since the group disbanded in 1983.”

Orchestre Kiam’s rights are still held by Verckys Kiamuangana, a one-time electrifying member of TPOK Jazz and solo artist who is almost as famous for being a ruthless business man as he is for being a gifted saxophonist . Lavoie has heard that Verckys signed an exclusive deal on his old Congolese music rights with the British label Stern’s, only to then turn around and sign another deal. Even the way he signed and sort of discovered Orchestre Kiam seems pretty duplicitous.

From Kinshasa’s Barumbu arrondisment, Kiam started playing music together in 1969 under the name “the Jacquis Boys.” They were named after a university student named Jacques who had inherited some money and decided to sponsor a musical group. It was a weird era in music.

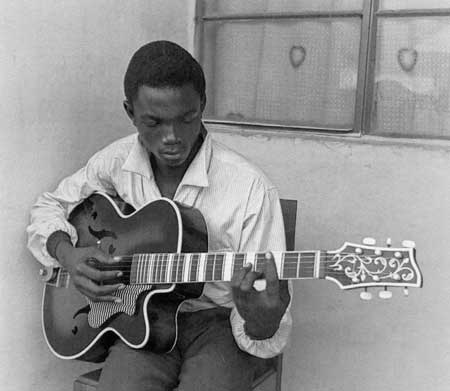

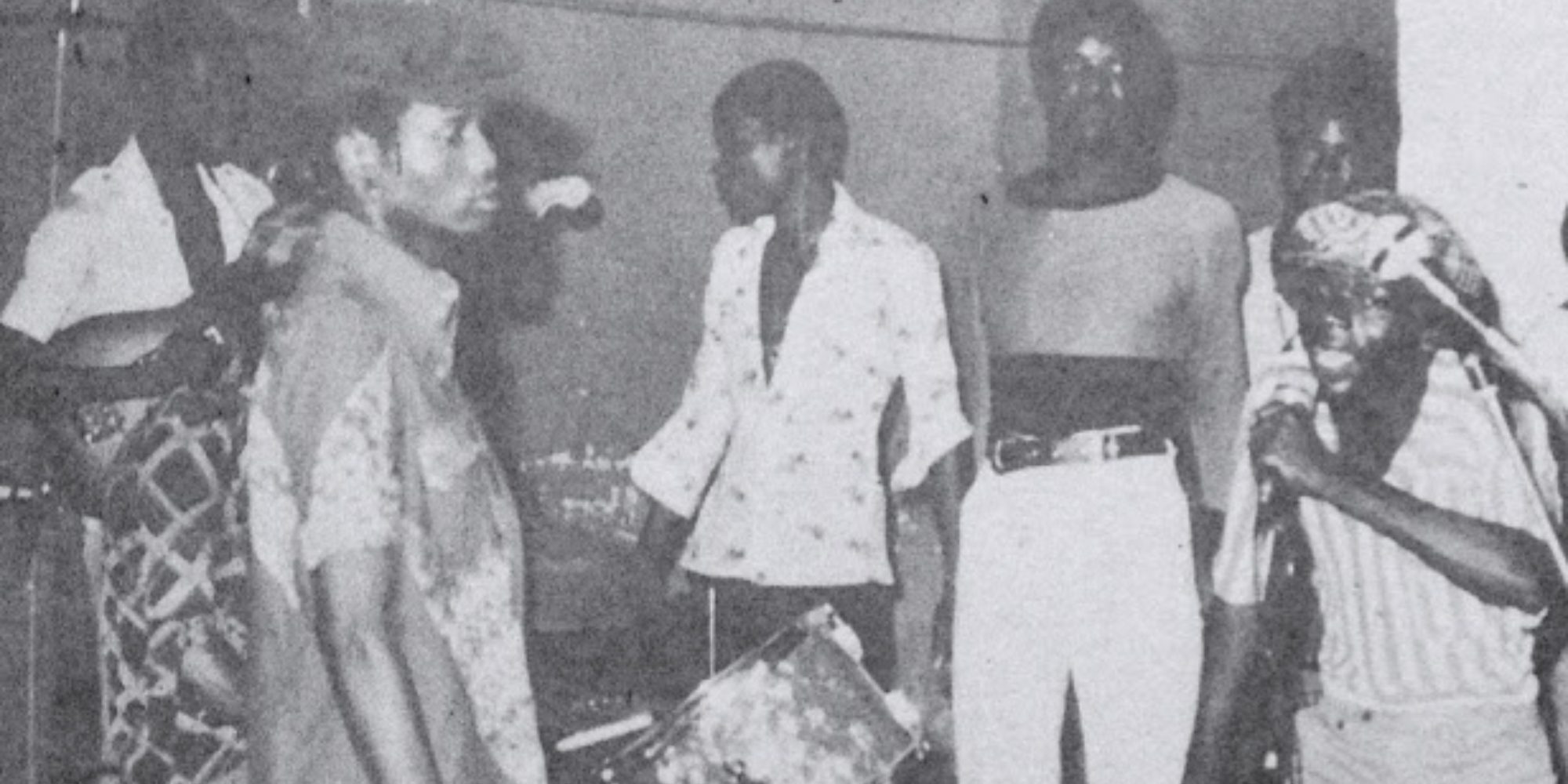

The Jacquis Boys gravitated towards Barumbu’s most famous musical son, "Papa Noel" Nedule. Nicknamed such for having been born on Christmas Day, Papa Noel was a guitar virtuoso who would go on to join Franco’s TPOK Jazz in the late ‘70s, but he had a long and storied career leading up to that, as the star guitarist in the groups Rock-a-Mambo and Orchestre African Jazz. As a bandleader, he had trouble paying his musicians, so after a concert in Algeria, Papa Noel found himself without a band. So he recruited the local Jacquis Boys to form his group, Orchestre Bamboula. While in the studio with Noel, the notorious impresario Verckys Kiamuangana heard them playing. When Noel was out one afternoon, Verckys swooped in and “stole” the band from Papa Noel. They became salaried employees of Verckys’s new Veve records. Papa Noel was pretty mad. In 1975, a competing producer did the same thing to Verckys—got Orchestre Kiam to record for him under another name. A furious Verckys suspended the group for two months without pay, which led to a lot of turnover when several band members sought greener, more forgiving pastures elsewhere.

You should check out the music and oral history yourself. The story of their group’s several dozen members' comings and goings comprises a whopping 41-page PDF that delves into the production and personnel who made songs like “Kamiki ,” a single that was so good enough it drove a man from breakfast and onto a journey.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles