This appreciation was written by Banning Eyre on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of Franco's death in 1989.

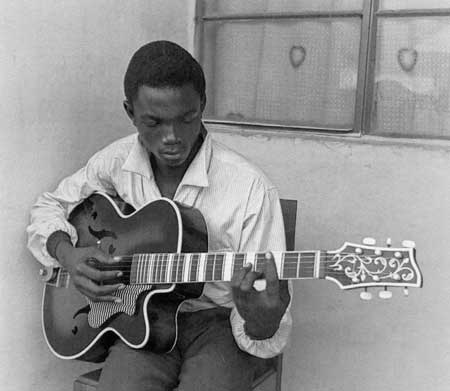

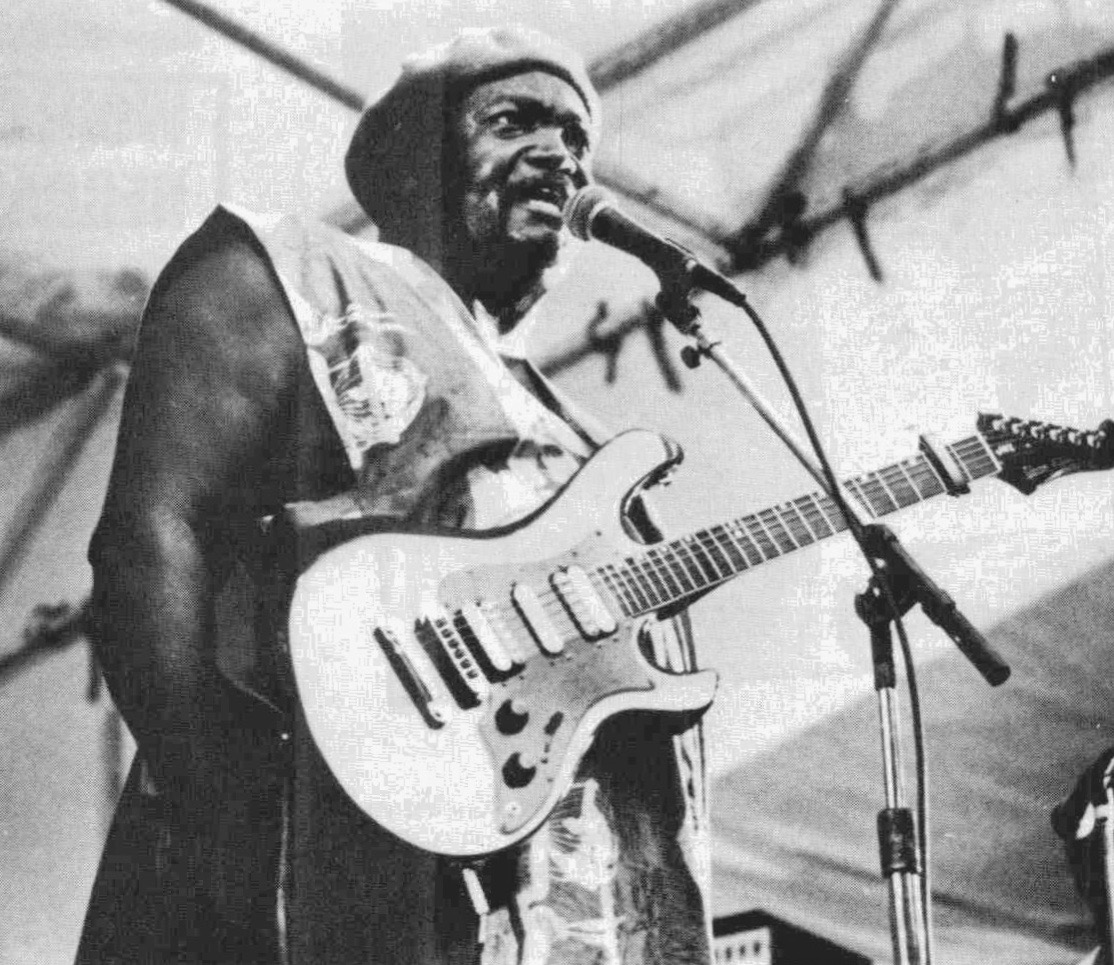

Twenty years after his death at 51, in October 1989, Luambo Makiadi, A.K.A. Franco, still stands as one of the greatest and most prolific bandleaders in African music history. Anyone who knows Congo music knows this. Near the end of his too-short life, Franco took offense that more Europeans and Americans, who were then discovering modern African styles, did not embrace him more vigorously. Why had no Western pop star asked him to collaborate? The man was a giant in Africa, beloved far beyond his linguistic and cultural base. Still, he seemed to sense that there was something about his music, even Congo music in general, that made it a hard sell in the West.

Franco thought his difficulty in coming across to Americans had to do with the long, complex song forms in Congo music. In fact, it had more to do with the deep roots of his music, which is embedded in Central African culture and overlaid with a veneer of Cuban music. For reasons of history, this is a difficult knot for Americans to penetrate. We relate more easily to West African sounds, which reflect the hidden heritage of most African Americans via the slave routes, and therefore the roots of blues, rock ‘n' roll, funk, and jazz—in short, our music. We don’t have to understand these connections in order to feel them. They are just there, like deeply encoded DNA strings. Contemporary music from South Africa also makes sense to us more readily, not because the indigenous ideas are familiar, but because the “modern” aspects in South African music reflect the country’s long-standing fascination with American styles, from ragtime to hip-hop. That’s enough to get us past the threshold. Congo music, for all its charm and beauty and its eminent danceability, has largely remained “other” to Americans, because the Congo’s ancient culture and its modern history scarcely intersect with our own. So even as African sounds in general have continued to seep into the Western mainstream, Congo music has remained largely a world apart.

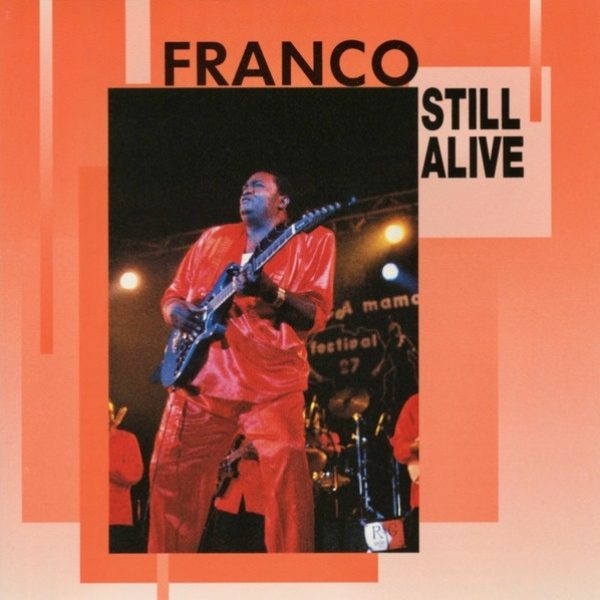

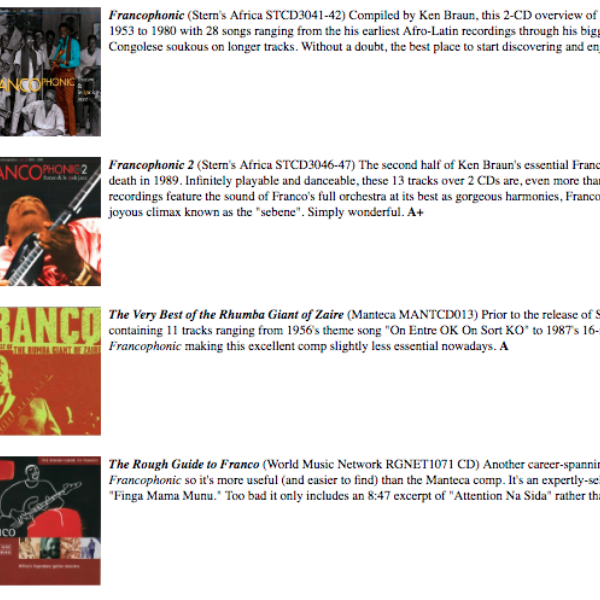

Were Franco alive today, he would probably still feel under-recognized. Within African music circles, his reputation has been steadily burnished over the years. Recently, four-CD retrospective—FRANCOphonic, Vol. 1 (1953-1980) and FRANCOphonic, Vol 2 (1980-1989) (Stern’s)—has provided an excellent entrée, without a doubt the most approachable packaging of Franco’s music to date. Congolese guitarist Syran Mbenza has just released a dynamic tribute album, Immortal Franco, and no doubt there are many more tributes now being produced and consumed by those in the know. As good as these releases are, they struggle to be noticed beyond the Congo music fold. Very few Congo bands tour in America any more, and with a few notable exceptions, not many American bands infuse Congolese elements into their sounds. By way of contrast, consider the fact that Nigerian bandleader Fela Kuti is the subject of a Broadway show, more than a decade after his death. Cities across America now support local Afrobeat bands modeled after Fela’s trademark sound. This has nothing to do with song forms or lengths, as Franco suspected. (Nobody’s songs are longer than Fela’s!) The difference is that we intuitively understand Afrobeat with its funk and soul references and pidgin English protests. Franco’s sound—all lush orchestration, layered rhythms, guitar alchemy and vocal lyricism lofting allegorical lyrics in Lingala—remains a specialized taste. Perhaps it always will.

Strictly on the merits, no African music stands the test of time better than Franco’s. His two-finger, double-stop guitar style sounds as fresh and riveting today as it did the day he invented it. The TPOK Jazz catalogue is unrivaled for its excellence in composition and arranging. The interplay of voices, guitars, percussion and horns is magical, the product of a fiercely competitive environment and a bandleader with larger-than-life personal charisma. What other band can boast such a strong lineup of singers and guitarists in particular, and overall talent throughout a 33-year run? To go back over the history of Franco’s creations, as the FRANCOphonic CDs allow one to do in fast motion, is to marvel at the man’s steadily evolving vision of what a song, a dance, a band, should be. I own a shelf full of Franco CDs, and I can reach for any one, at anytime, on any day and be glad I did. The music simply does not age.

Less obvious to the foreign listener, Franco’s lyrics offer a study of an emerging African urban society. Writers have compared Franco’s output to Balzac’s, and with reason. The songs present a world of posers, double-crossers, philanderers, lovers and tricksters. They are laced with what the Congolese call mbwekela, a verbal art of coded criticism. Franco enjoyed hot-and-cold relationships with the powerful, most notably with the long-standing dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, who was Franco’s biggest fan, but who scrutinized each new song for subversive hidden messages. Debates about what Franco may have really meant by this or that lyric continue to this day, and they will never end. It is hard to imagine that there will ever be another figure with Franco’s particular combination of mercurial musical genius, political savvy, verbal wit, and personal complexity. He shepherded some 1200 songs into the world, some of them works of near-classical grandiosity.

Franco’s oeuvre offers unparalleled insight into the urban realities of the Congo as it emerged from the trauma of Belgian colonialism into the trauma of strong-arm dictatorship, and then societal breakdown and civil conflict. The Congo remains a grim fascination for historians. How to explain the country’s monumental disfunction? Is it the inevitable byproduct of a nation made up of some 230 ethnic groups, none of them dominant? Or perhaps of the singular brutality of King Leopold’s perverse and craven rule? Can it be pinned on the meddling of neighbors, keen to control the Congo’s mineral resources, as so many would have it? Or is it something deeper than history and geography, something buried in the psyche of an ancient and long-tormented people? As scholars hunt for answers to such questions, they would do well to study the songs of Franco.

The anniversary of Franco’s early death offers a chance to revisit a splendidly chaotic life and an extraordinarily satisfying body of musical work. The intrigues of that life are wonderfully chronicled in Graeme Ewans’ book Congo Colossus (Buku Press). Ken Braun’s extensive and well-written notes to the two FRANCOphonic volumes skillfully interlace the intrigues of Franco’s life and times with the words to his songs. Both are highly recommended. Franco’s story isn’t likely to hit Broadway—though it absolutely deserves to—and you won’t find many Franco samples in today’s hip-hop songs either. But anyone who makes the effort to discover this man and his music will be richly rewarded. Franco’s sound has already outlived the world that created it. It is a sonic monument to a unique period of history, and a cultural treasure that will endure when a thousand world music trends, and all of us, have gone the way of Franco.

Related Audio Programs