Afropop fans are likely familiar with the life and music of the late Johnny Clegg, the South African-born English boy who snuck out into the Zulu townships during apartheid and befriended Zulu musicians, eventually learning their language, guitar style and dances, and then founded two of the most significant bands in South African music history, Juluka and Savuka. At the heart of Clegg’s sound is the Zulu traditional guitar, concertina and vocal genre called maskandi, (sometimes maskanda). It’s a seductive, soulful, elliptical finger-picking style on guitar that somehow has never really caught on in the U.S., despite Clegg’s popularity.

David Jenkins—aka Qadasi—does not consider himself a latter-day Johnny Clegg, although one could be forgiven for thinking of him that way. His story is quite different, very much a product of post-apartheid South Africa, but what the two share is deep mastery of Zulu language, guitar and concertina, and an instinctive urge to fuse that music with Western folk styles.

Qadasi—Zulu slang for a white person—has amassed a strong following in South Africa. He has released six albums since 2011 (four of them with Zulu guitarist-singer Maqhinga), and toured in Europe, but somehow, he has escaped our notice until very recently. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Jenkins over Zoom to hear his remarkable story and learn more about his music. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: David, nice to meet you.

David Jenkins: Wonderful to meet you too. Thank you.

I came across you when a guitarist reached out to me wanting to learn some maskandi guitar riffs. He was pretty much a beginner, so I showed him something pretty basic. I don’t know a lot, but enough to give him a start. Then later, he sent me links to your stuff and said, “Hey, have you heard of this guy?” I had not, so here we are.

Wow, that's amazing.

Yeah, it's funny. So to start, tell me your story. How did this all come about?

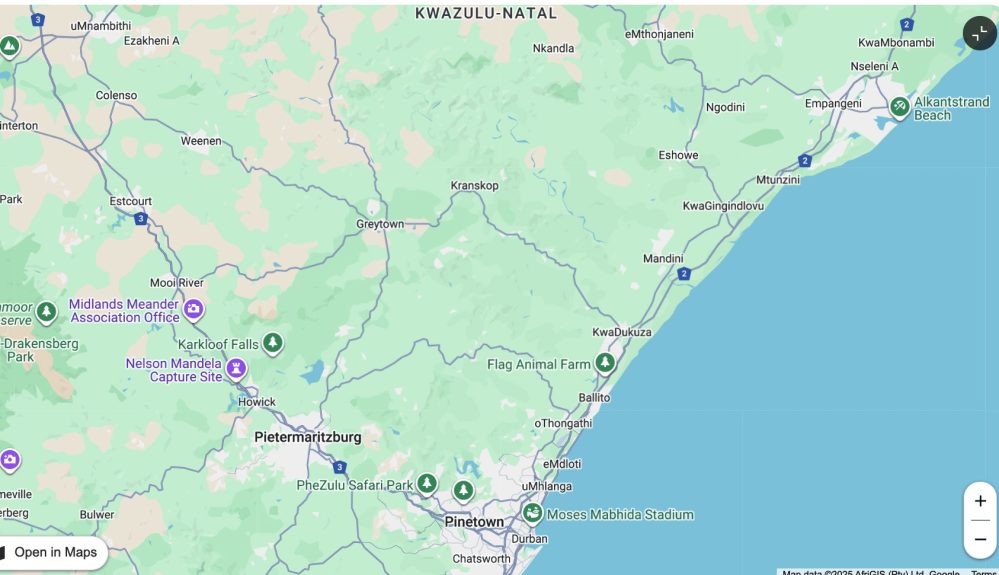

Well, I was born in 1992. So I'm 33. I grew up in Zululand, in Northern Zululand, in a little town called Empangeni. This is in the heart of Zululand. I used to travel around Zululand and Kwazulu-Natal province with my late father, who was a journalist.

Okay.

That’s how I discovered the Zulu and learned about Zulu history and everything about these incredible people. So history, music, culture, regalia, anything to do with the Zulu people, and I was absolutely fascinated. And I was right there. I was growing up in the middle of this, but I wasn't on a farm. I grew up in the little town of Empangani, but when I went out into the rural areas with my father, that's when it really all came together, you know. All of this, the history of King Shaka, the Anglo-Zulu war of 1879. All of this happened in this area. So from a young age. I wanted to learn more about all of this.

So was it because of your father's journalism work that you lived there?

Yes, so I was born in Pietermaritzburg, and I'm currently actually based in Pietermaritzburg. And when I was two, my father was working for the Natal Mercury, and the Mercury needed to set up a bureau in Empangani in Northern Zululand, so they asked my father to head up that bureau, and so the family moved. That’s how we landed up there.

Those were tough times there, weren't they? There was some serious violence going on, right?

Yeah. That was 1994. That it was when it all happened. New governments. New change. Freedom. I mean, it was an important time for this country.

A lot of vying for power in the new order.

That was it. They needed my father in northern Zululand to start covering all that, heading up that bureau, and to be in the thick of it. Obviously, I was really young then, but it was just fascinating, being in that part of the country.

How did you go about learning the language, dance, the guitar, all those kinds of things that you seem to have learned rather well. How did you manage that in such a turbulent environment?

My interest started with the history, and obviously just being totally immersed, and seeing the colorful regalia, the skins, the vibrancy, everything to do with these amazing people, and I inevitably stumbled upon maskandi, traditional Zulu music, essentially played on Western instruments. When we would go to various events, there would be entertainment, and the entertainment usually consisted of either traditional dancing or traditional maskandi artists on stage.

Then I started listening to old cassettes of legends, all the maskandi greats, and I became obsessed. It just blew my mind how incredibly powerful all of this was! You had all these traditional, powerful melodies and scales that were being played on guitar and bass and violin and concertina. After a while my parents introduced me to the music of the late, great Johnny Clegg, the pioneer of this fusion of traditional Zulu and Western folk music.

So you came to Johnny Clegg after you had been immersed in the authentic, undiluted maskanda music.

Yeah, absolutely.

What was it like when you became aware of his story and his music. I imagine you saw him perform a number of times.

Yeah, yeah. So at first, I'd obviously been listening to the really traditional stuff, and then here you have this white guy with his partner, and the two of them creating these incredible compositions, this crossover of traditional Zulu and Western folk. By the early 2000s, Johnny had gone through Juluka. He'd gone through Savuka and started his solo career. So I had all of that to listen to. I was mainly focusing on the early days, the really traditional stuff, because that was what I loved.

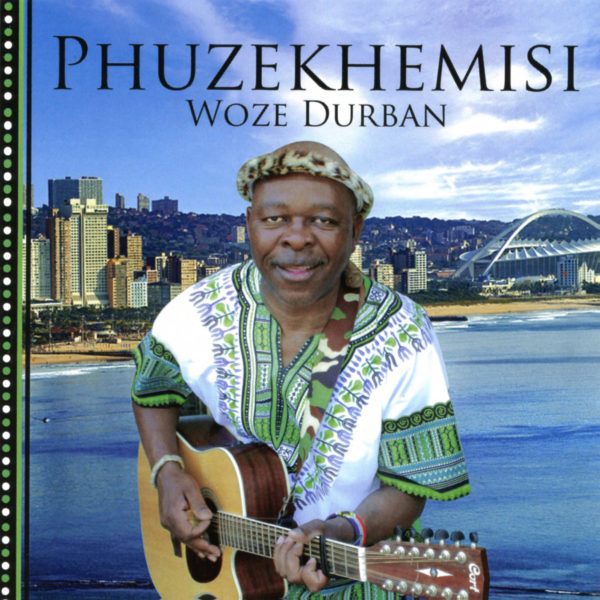

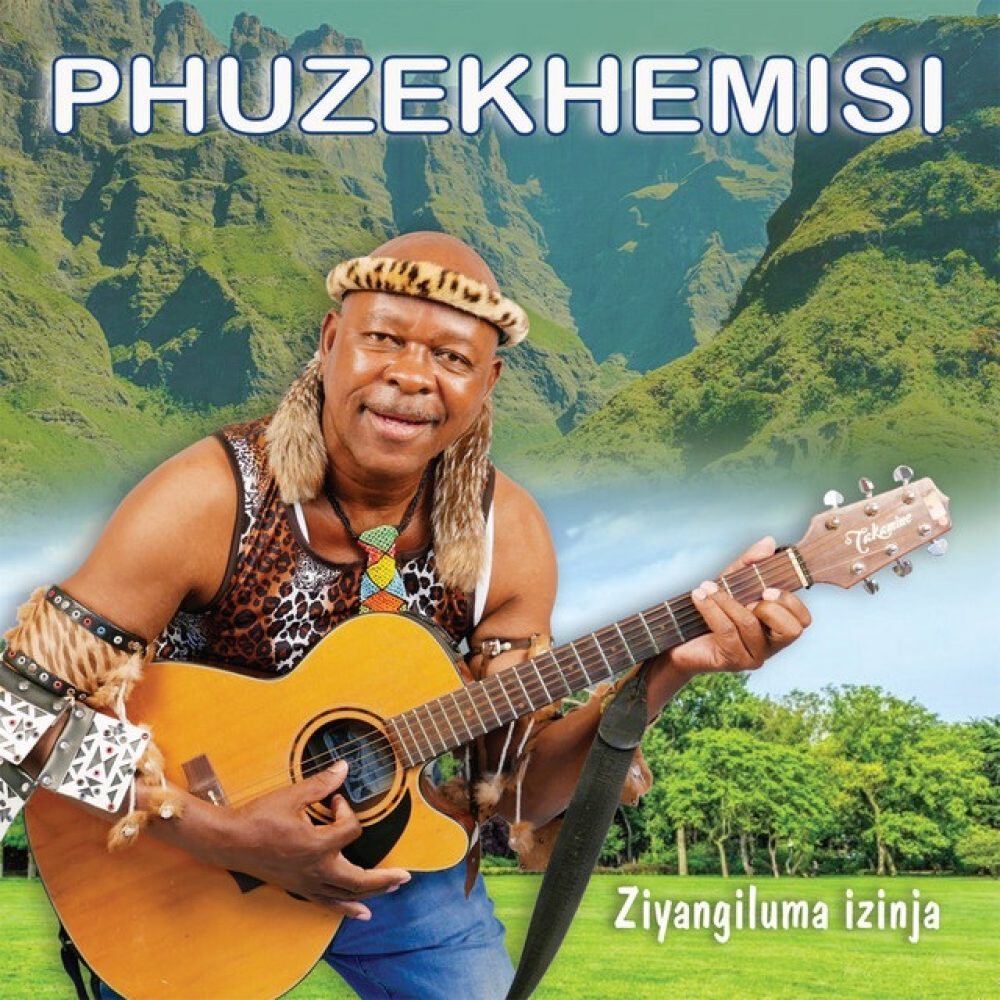

And so here you had these Celtic melodies, these Western folk melodies with these traditional Zulu choruses. And you know, obviously the picking, the very unique style of maskandi guitar. That blew my mind. I got my first guitar at the age of 12, for my twelfth birthday. I mean, my goal was to be Phuzekhemisi.

Really? When you picked up the guitar, that was the goal, to become a Zulu-trad pop star.

That was it. And you know, at that stage it was very much the traditional stuff, but obviously I was listening to Juluka and Savuka as well. But the focus was always the real traditional maskandi. I always need to make people aware of the fact that I didn't just wake up one day and decide to be a Johnny Clegg. It all started with traditional music. So you had Johnny and Sipho [Mchunu] putting it together for me and just taking it to another level. So I slowly developed my maskandi guitar riffs and melodies.

I didn't have a teacher back then. It was very much learning the basic Western chords. My uncle taught me my first few chords, and then I started picking up that style by watching, by slowing things down over the years, you know, as technology advanced. I slowed down videos that I found online of Johnny and of other traditional maskandi artists. And I would just try and pick up those rhythms. But the most important thing is all about the thumb and the forefinger, the thumb playing those bass lines.

It's amazing how many finger-style African guitar traditions just use thumb and forefinger for picking. Whether it’s Mande guitar in West Africa or palm wine guitar—it’s always those two digits working together.

Yeah, yeah. Basically, you’ve got notes being played against each other. It's a complex style. It's not easy, and for anyone to learn this style, you have to listen to it. You have to have an understanding of it. It's not just having a general understanding or a general interest in maskandi. You need to understand that there are seven or eight different styles of maskandi within the maskandi umbrella. I had understood that, and that helped hugely with taking my guitar skills to various levels.

So this continued on for years during school. I was very shy growing up, but I got to the point where I needed to get onto a stage. My teachers and my parents and everyone, my friends, would listen and say, “Why don't you get onto a stage, and play us a few songs for the school concert?” And so I finally gave in and started to hit the different stages. That was when I started playing for audiences and receiving audience reactions. And I slowly, slowly realized that: “Wow! There is something here.”

How did you start actually working with Zulu musicians and performers?

So I was growing up in Empangani, such a small town in the middle of Zululand. It's about two hours north of Durban. So it's a long way from the professional industry. So when I was growing up, it was difficult to find guys who were interested, or who could show me the ropes and so on. I think it was in 2009 that I was part of SA’s Got Talent, South Africa's Got Talent. I got through the first round, but I didn't get any further than that. And thank goodness, because I wouldn't want to be labeled as “He won on SA’s Got Talent.” But it gave me that exposure. I was on a professional stage with a judging panel and a wonderful audience of mixed colors and cultures.

Anyway, the reaction was what told me that I could potentially take this to another level. That wasn't the goal. This was a year before I matriculated and ended school. I wasn't going to become a professional musician, but then it was SA’s Got Talent and a few other shows that showed me it was possible. That gave me energy and enthusiasm.

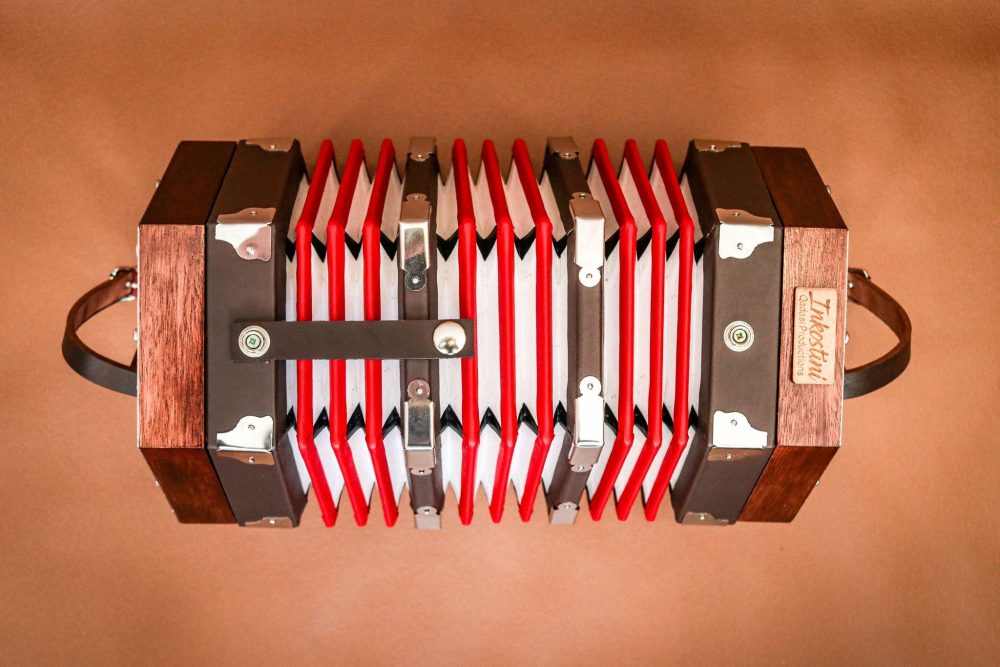

2010 was my final year of school, grade 12, and I decided I wanted to learn how to play the squash box, the concertina. The concertina plays a huge role in traditional Zulu music. Maskandi is mostly between the guitar and the concertina. Those two are the front runners, and so I wanted to learn how to play the concertina. But in order to play the Zulu concertina, it needs to be reconfigured, retuned.

Yes. I remember Johnny talking about this. You need a specialist.

Right. Only someone who understands how to do this can get it done.

There are no YouTube videos on that.

There are certainly no YouTube videos on that.

So my mom helped me hugely. In early 2010, we we started hunting for someone who could tune this concertina for me. I had found one, but it was tuned to the Western layout. So we called artists in Durban, in Joburg, and we finally got hold of someone who said, “There is a man by the name of Maqhinga Hadebe, who lives in Durban. He is a highly respected maskandi artist and he will be able to find someone to do this for you.”

So we got hold of the details for Maqhinga and my mom gave him a call one day and set up a meeting. He said. “Absolutely no problem. I know exactly who can sort that out for you. Let's meet in in Durban, and we'll get it done.” So we set up a meeting and headed off to Durban one day. At this stage my father had already passed on. He passed away in 2008. So it was just my mother and I and my younger sister, and the three of us went off to Durban and met up with Maqhinga in a studio. I took my guitar along as well. So we met up with Maqhinga, and from the get go, he was the most amazing man, humble, just the nicest man. At that stage I didn't realize how much of a legend he was, how much he had done in the past. I'd heard of the group that he was part of which was called Shabalala Rhythm.

Shabala Rhythm! I love that band. They are fantastic.

Yes. Absolutely amazing, beautiful stuff. So Maqhinga was the guitarist. Still is the guitarist of Shabalala Rhythm. The leader is Sibongiseni Shabalala, who was part of Ladysmith Black Mambazo. I had no idea at the time.

So, me and my mom and my sister, we all went down to the Dalton hostels in Durban. There's a place called the Dalton Skin traders in downtown Durban, and this is where you'll find regalia: traditional skins, drums, anything to do with traditional Zulu culture, and in one of those little stores there’s a man by the name of Mr. Ngcobo. He sits there, day in and day out, making or fixing and tuning concertinas. So we dropped off my concertina with Mr. Ngcobo. He took that, and he would spend the next three hours working on it. While he was doing that, we all retired to the studio and sat down with Maqhinga. I took out my guitar. He took out his, and we had a jam session. He didn't realize that I was already playing maskandi. And we immediately just clicked.

That was it?

Absolutely so. We hit it off immediately, and we had an incredible jam session. We played a couple of really old maskandi songs, Zulu war songs, a couple of my own compositions, and it was the most amazing three or four hours.

After that, we picked up the concertina, which was beautifully tuned to play Zulu music, and we went off home. It was just the most amazing day, and next, I think it was about a week or two later Maqhinga phoned me and told me that Sibongiseni Shabalala owned that studio and wanted to meet up with us and just have a chat. So we met up with Sibongiseni and Maqhinga again and Sibongiseni offered me a record deal. That was the start of my professional career. It was during the last year of school, which was not easy. It was tough. But most importantly, it was the start of my very deep friendship with Maqhinga. It all started there. He became my mentor and my producer.

What a story.

So then I moved to Durban. The year after that he started teaching me new styles of maskandi, and taking what I had to another level. That was the start of everything for me, musically, professionally, and just being part of the maskandi world. The main focus then—this was 2010, 2011, 2012—was my solo project as Qadasi, which is my Zulu name. Qadisi is another word for white person.

Ah ha. Like toubab in West Africa or murungu in Zimbabwe.

Right. So Maqhinga helped take that brand to another level. Then in 2013, we started doing more and more together as a duo. We started experimenting, sitting in studio for hours and hours, jamming together and working on material. We realized that there was something special there. I mean, it's all fine and dandy doing the solo Qadisi project, and Maqhinga having his own solo project. But the two of us sitting there… I mean it was real. As I said, it wasn't as though this was something new that I wanted to do all of a sudden. I'd been doing it for years. I was absolutely passionate about it. So that was when it really got rolling with Maqhinga.

Did you guys form a band then, or did you just go as a duo?

Mostly as a duo. It was just something that worked, something that was different. You know, there were plenty of maskandi bands and other Afro bands. But we liked that acoustic sound, just the guitars. By then, Johnny had gone through all those stages with his various bands, and you know, so we weren't pretending to be a new Juluka. We had access to an incredible band, a bassist, drummers, a keyboard player… But there was something about that acoustic sound with just the two guitars, the vocals, the concertina and a bit of kick, a bit of percussion. That was our main focus.

On the odd occasion, we would try things out with a full band. There were a few big shows in 2013. That was an incredibly special year for us, because we opened for Johnny. He had a huge concert in Durban at the Botanical Gardens, and the organizer of the that event got hold of us and said, “Listen, Johnny's playing in July. Would you guys like to open for him?” Oh, gosh! So that was very special indeed. I had met Johnny previously, before I started professionally. I met him at a show in Pietermaritzburg a few years before. My mother organized it. She somehow got through to the management and said, “Listen, there's this young boy who plays maskandi and absolutely loves Johnny and what he does.” And somehow she got it right, and I was able to meet Johnny backstage. So there we were in 2013, opening for him with my band—just an incredible experience.

I bet he was impressed. And I’m guessing he was supportive.

Absolutely. For me, that was the most important thing. It was just having his approval, his support to say, “I see you, and I respect what you do.” For me that was everything. I was totally happy thereafter.

That's great. So how many albums have you done now?

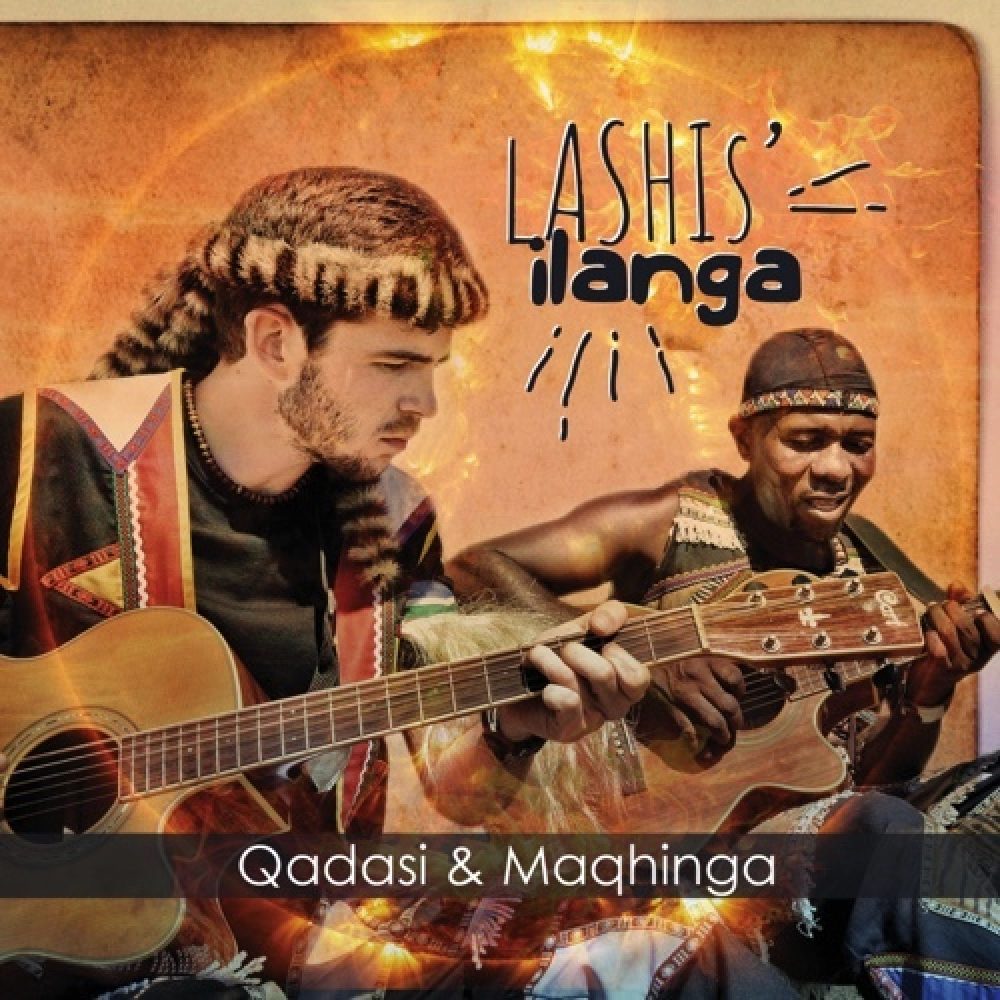

I released two solo albums with Maqhinga as my producer. I recorded the first one, Child of Africa, during my matriculation year. That was in 2010/2011. I then released another solo album, Uhambo Olusha, a couple of years later with a full band. And then, because Maqhinga and I started working together in 2013, we had a couple of years where we didn't release anything. Then in 2016, we decided to work on a duo album, with just acoustic instruments, acoustic guitars, concertina and vocals. That was Lashis’ Ilanga, and that went on to it received a nomination for a South African Music Award, which is the equivalent of our Grammy awards here in South Africa.

That made us realize that there was something special there. Another thing with that album is that I had a lot to do with the production. I realized how passionate I was in the behind the scenes of the music, not just composing and playing, but being part of the production. And here, thanks to my mentor, who was who played a huge role on that and the production of that album, Marius Botha, an amazing producer and engineer from Durban. He's a lot older than I am, and he became not just an incredible friend, but also a wonderful mentor. He made me realize that I could do this, moving forward with something that I could do just by trusting my ears. So then, I started doing lots of production work for our own music, and I did a few productions for other artists. But that release was big for us. And then we went on to record our second collaborative album, Ungabanaki, in 2019. That won a SAMA (South African Music Award) for Best Traditional Music Album in 2020. That was during the first year of COVID. So it happened at an unfortunate time, but the bottom line is, we won a SAMA award, and we were just absolutely thrilled.

Wonderful. I need to hear all of these. But I’m curious. I have my own story of learning African guitar in various places. It’s a choppier story, because it happened episodically in Mali and Congo, Zimbabwe and Madagascar. I'm wondering if you ever experienced any sort of pushback from the Zulu community. We know Johnny’s story which started with his social immersion and the music grew from there. What's been your experience of personal interaction with the Zulu community?

Well, firstly, during my school years, when I was starting to play on stage, the reactions at school were just amazing. Obviously there, it’s a little easier because you have your peers and friends in the audience. But that was a good start for me, to get those positive reactions. And then I started playing for the public, for example, SA’s Got Talent and other smaller events that were being hosted in the Zululand area and in the region and in Durban. On stage, I was still amazed by the positive response. Then, from 2010 and 2011, I started releasing material and doing interviews on Zulu radio stations. That was when the public at large, including the Zulu public, started finding out about my project.

So at first, obviously, there were many who would have questioned it, and wondered, “Is this guy the real deal? What’s going on here?” Which is understandable. I mean, it’s totally abnormal, which is sad, to find a white guy playing traditional Zulu music. Johnny was the pioneer of that, but since then, there have been very few white people who have really gone out and learned and been part of this music culture. So, yes, I had to prove myself. I had to show the public that I wasn't taking a chance here. This was something that I was passionate about. I'd been doing it for years. I didn’t just started doing it, and get thrown into the limelight. I'd been doing this since I was 12.

Your ability itself was probably the best possible calling card. If you can show that you can actually play the music, that dissolves a lot of barriers.

Absolutely. That's it. The best way to prove yourself is to get onto stage and play your guitar, sing, and talk to the people. That is the best way to prove yourself. Nowadays, you go into Tik Tok or Facebook or Instagram live, and you know immediately. They can pick up immediately what the deal is, and whether you're taking a chance or not. Back then, it was a slow process of going onto radio and getting your song out there, going onto YouTube and hoping you'll get views on YouTube. And it took time.

Eventually, with Maqhinga, we started doing more and more TV spots, and getting music videos playlisted on TV. That was what hit it off for us. It wasn't necessarily the radio for us. It happened to be TV. There are a couple of TV stations that specifically play traditional maskandi music. They started playlisting us big time, and that was such a huge help, just showing the public that I was genuine. So generally, it's been very positive. For me as well, it's important to go into the communities, for example, Maqhinga’s village to visit his family, his friends, to be part of that community. That's how you're welcomed. You show an interest and speak the language. This wouldn't be possible otherwise. If I was able to play maskandi, but not be fluent in Zulu, I mean, it just wouldn't be the same thing.

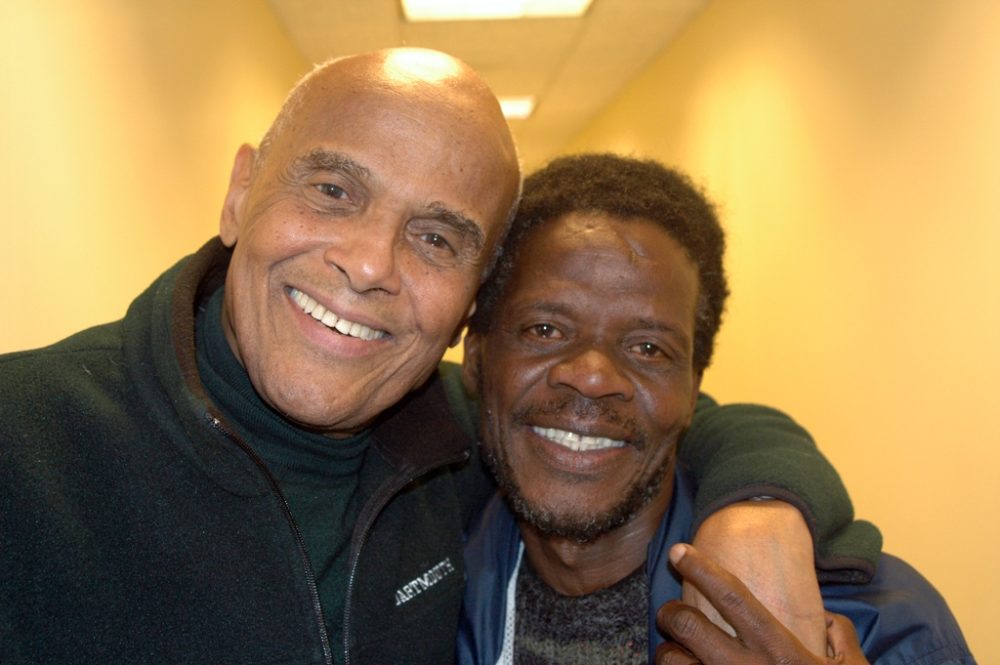

I'm interested in the trajectory of maskandi music. Here in the U.S., Johnny Clegg had a big audience whenever he would play. It wasn't stadiums, but he would pack clubs, and had a very loyal following all over the country, including a lot of South Africans, but many Americans, too. But that never translated into an open door for maskandi traditional artists. Phuzekhemisi once played as part of a South African festival in New York. And Carnegie Hall brought Shiyani Ngcobo for a single performance in 2011. I was actually asked to help with that one. It was during winter, freezing cold, and I rounded up a bunch of winter coats and sweaters for them, and spent a couple of days in the hotel with them. I have some video of that experience. The show was fantastic. I remember that Harry Belafonte was there and went backstage to greet the musicians.

But the genre has no profile here. We have an active community of people here who play Zimbabwean mbira and other Shona traditional music. There are a few West African kora players, and tons of djembe players. There are percussion with almost cult-like followings around the country, and they talk to each other. But that doesn't exist at all for this music, despite how incredibly appealing, and despite the fame of Johnny Clegg. We at Afropop have done shows about it, but sometimes you feel like a voice in the wilderness.

I was in Durban doing research in 2019. I spoke with maskandi scholar Kathryn Olsen, and the late Zulu music broadcaster Bhodloza “Welcome” Nzimande. The impression I got from talking with them was that the maskandi recording and performing world was big and strong, but quite contained. It didn't bleed out into the big popular mainstream music of South Africa. Is that your impression? What would you say about the state of maskandi music now?

I would say, maskandi is one of the biggest genres of music in South Africa in 2025. It is one of the biggest selling genres, right up there. However, that is maskandi as a whole, but the pop styles of maksandi have taken over traditional maskandi. So if we look at the big big names at the moment, we can look at the likes of Khuzani.

He's sort of self, proclaimed King of Maskandi . He is certainly one of the kings of the pop style, one of the top runners. And the list goes on. There are dozens of top-selling pop maskandi artitsts. And most of these artists cannot play a note. They've never picked up an instrument before. It's moved right away from the guitar and the concertina. If you hear those on a track, it's played by a session musician. The “leader” of that group, the majority of the time is no longer a musician. He's a singer, but that’s it. He cannot play the guitar, or the concertina, or the violin, or any other any other instruments. So this has moved away from the way the music was 20 years ago.

Thankfully, when I started getting into this traditional maskanda, it was still big in the early 2000s. That old school style was still big. But nowadays, if someone comes out from the States or from Europe and wants to go and experience a maskandi show it is very difficult to find a true traditional one.

Yes. I was told that, even back in 2019.

So that is the state of the industry. Maskandi as a whole is right up there, along with gospel music and Afrikaans music and amapiano. But for us, playing traditional maskandi, we are sidelined. We are highly respected in the industry, but we are not part of maskandi festivals. We aren’t on radio, and we are not often not playlisted because we play traditional maskandi music and we play it live.

So when you won that that the album won the award in 2019 for Best Traditional, not maskanda?

Exactly. Separate category from maskandi. Even though, essentially, we are maskandi artists. The traditional category is for anyone who is taking traditional styles and working on them. So even though we are adding in other styles, like Western folk, it’s got that bluesy, jazzy traditional feel. So that’s why it falls under the traditional category. That is the state of things.

So I, personally, and if you talk to Maqhinga and other traditional artists, we feel that all of these maskandi pop songs sound the same. You've got the same session musicians playing on the tracks. You've got the same drum samples being used for every track, and that's the current state of the industry.

And yet it's still a huge seller.

Massive.

Well, your story is great. I'm really pleased to meet you. Someday I'd really like to get down there and hang out, and, meet some of the guitarists who still do play traditional. Let me ask you a little bit about the guitar style itself. You say there are seven or eight different styles. Are you still learning new things all the time? Is this the kind of tradition where you can just be constantly learning new things because there's so much. Or do you feel like you've really got a handle on it?

I think it's like other complex styles where you don't stop learning. Basically, how it works is in the Kwazulu-Natal province or region, you've got styles that change from region regions within the province. So northern styles will sound different to southern styles, and you go inland towards the Drakensburg Mountains, the Bergville area, those styles sound different. So all around this province, you have different styles. There’s a slight similarity, but then there's something you can pick out that makes each one different. That beat is different, or the progression is slightly different.

That’s what I picked up on from a young age. I could tell which styles I preferred, and I always preferred the really traditional ones. Basically, you have those traditional styles that are very strict. So you stay away from third harmonies and you focus on your fifth harmonies. Your fifth harmony is always considered to be where the power is.

Yeah, that's it.

Those are the styles I fell in love with. And so you've got maybe four or five really traditional ones that are all slightly different. Then you've got your more jovial, jivey songs, which use your I, IV, V chord progression, where you use thirds harmony. It's very similar to more Western styles. And that's what you would hear moving north into Zimbabwe, and into neighboring countries. That's your classic three-chord African style. It's upbeat. Those styles are great and there's a place for that. It's party music. But for me, personally, it's those powerful traditional styles, so that's where my focus has been over the years. So on the guitar, generally speaking, I'm fairly accomplished, very accomplished in specific styles. I’m fairly accomplished with all of the traditional ones, and with the more Western ones, which I don't specifically focus on.

So that’s guitar. The concertina is a very complex little instrument and I am more accomplished in specific styles there. I still learn; every day I'm learning; and I've been playing this for years now. There are so many incredible things one can do on this little concertina. You can never get to the end. You can always take it to a another level.

I love that. I feel exactly that way about the Malian and Zimbabwean styles I’ve mostly played.

I remember the lesson I had long ago with Johnny. He showed me some pieces where he was tuning the high E down to D. It's like a high drone. But on some songs, he didn't do that. Are there other tunings?

So that high E to D is essentially a drop-d tuning. In the Western world, you also have a drop-d, but it's usually the low E you drop, not the high one. The standard Zulu tuning is your drop-d with the high E down to a D. That is the standard for me. My guitar sits on that tuning 100% of the time. I never change it to anything else. And that goes for Maqhinga too.

With most maskandi artists, it's going to be that tuning. But if we look back to years ago, maskandi artists would sometimes really experiment and change a few of the strings, totally tune them differently. In the Western world, you've got guys who like to play with an open G or an open D, you know. And so that's the way it was in the maskandi world. You had artists who would really go all out and create their own tuning that worked for them. That’s not too popular nowadays. Generally speaking, it is the standard Zulu drop-d.

Thanks for that. One more question I have for you about the state of guitar music. There was a concern back in 2019, when I was talking to people in Durban, that there were not many young people learning the guitar styles, because they were all going in the direction of the pop sound. What’s your take on that? If you were to go around Zulu land with a recording project where your goal was to record young maskandi guitarists, how hard would it be to find them?

Actually, thanks to Tik Tok and different forms of social media… I don't spend a great deal of time on those platforms, but if I do scroll through videos of musicians, I've been quite amazed, especially in the last couple of years, to see the number of young musicians picking up Zulu guitar. And so I actually think, since you were in South Africa in 2019, which was not long ago, the interest is growing, which is fantastic.

And if you really think of where this all started. If we look at Phuzekhemisi and Mfaz’Omnyama and all these guys, these legends, and see how this all started, I actually think it's slowly, slowly, moving in a positive direction. You've got more and more young Zulu musicians who are interested in picking up a guitar and a concertina, and it's wonderful to see. I hope it just grows exponentially from here.

Well, I share that hope, and I do plan to get over there and meet you and some of them one of these days. Thanks so much for sharing your story.

Thank you.

Check out Qadasi's YouTube channel for more great videos.

Related Audio Programs