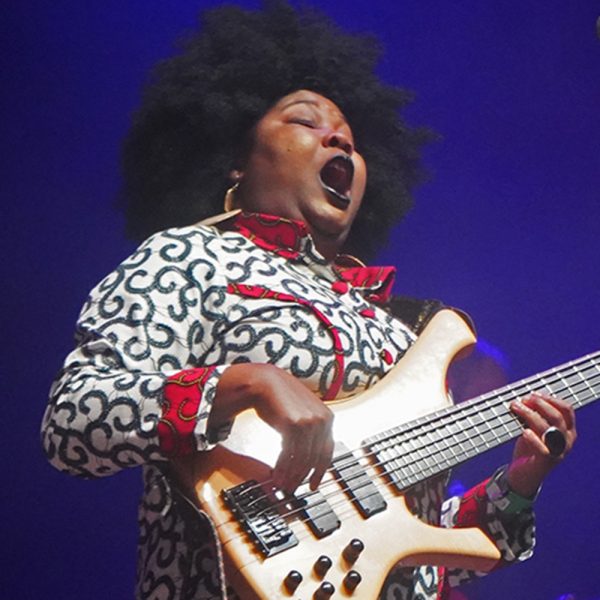

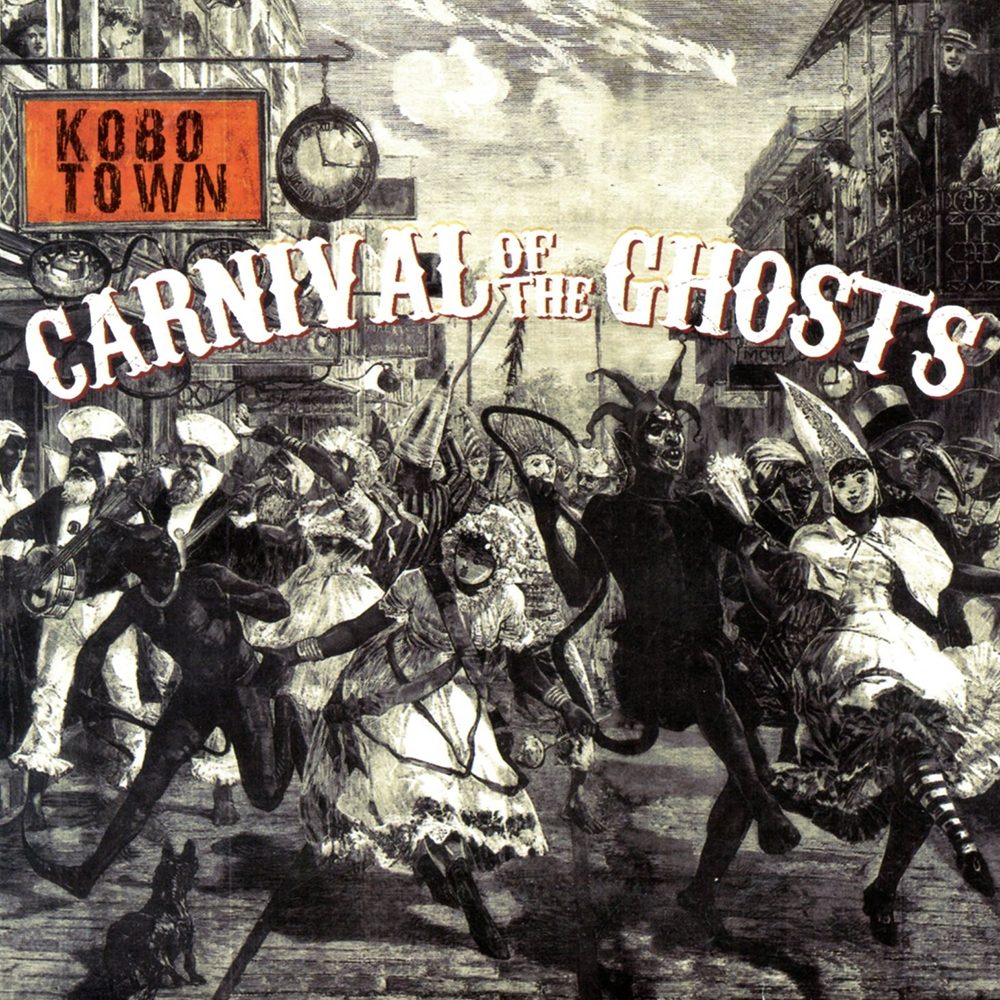

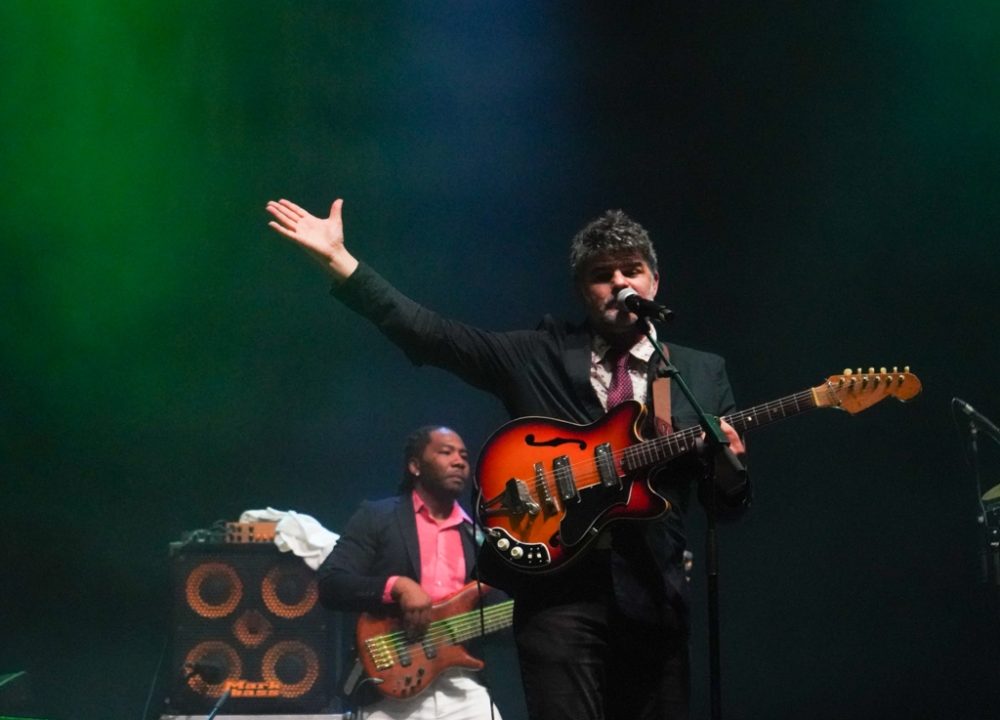

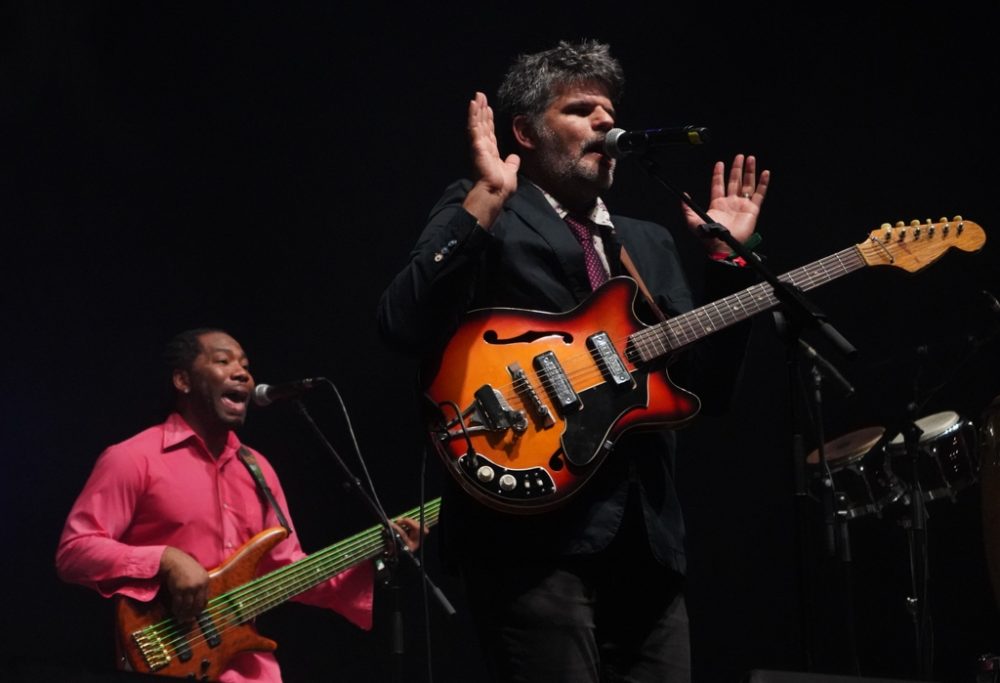

Drew Gonsalves is the Trinidad-born, Toronto-based leader of the calypso band Kobo Town. You could think of them as a revival band, because they play the music in the live, swinging, pre-soca style. But that’s not the whole story. Gonsalves is a fine composer with a stinging wit and deep insights into the human experience—a key element in classic calypso. Kobo Town played a joyous, high-energy set on the last night of WOMEX in Porto, Portugal, in October 2021. We didn’t manage to catch up with Gonsalves in Porto, but Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Gonsalves by Zoom to talk about his life and Kobo Town’s new album, Carnival of the Ghosts. Here’s their conversation.

Where am I reaching you, Drew? Toronto?

No, I’m in Aylmer, Québec, just across the river from Ottawa.

Familiar territory for me. My sister lives in Ottawa. So Drew, I've been listening to your music for quite some time, but I don't really know your story. So let's start with that. How did you wind up leading a calypso band in Canada?

Well, you know, I grew up in Trinidad, in Diego Martin. I can't say growing up there I was particularly interested in calypso music. I think like most other middle-class kids, my tastes were more for foreign things. I was a big heavy metal fan.

Really?

Yeah, yeah. Iron Maiden was my favorite band. I heard calypso a lot. Growing up in Trinidad, you are very exposed to it. When I was about 13, my parents split up and we moved with my mom to Canada, which is actually my mother's home country. She was like an army child. She grew up on military bases all around Canada. Mostly in Québec and the Maritimes. Anyway, we ended up in Montréal briefly, and then Ottawa, and then I wound up moving to Toronto.

Our departure from Trinidad was complicated and very abrupt. So when I came here, I missed it a lot, you know, and the schoolmates I loved very much. I guess it sent me on this backwards journey. I think this is a typical experience for people who move from one place to another. Things that I took for granted suddenly stood out in contrast and were all of a sudden treasured and valued, and one of those things was calypso music, which I then rediscovered.

I have this friend from Grenada who gave me this compilation of really old-time calypso from the 1920s, ‘30s, ‘40s, and then some more contemporary stuff at that time. And I was just captured. It seemed natural to me, growing up in Trinidad. I was really taken by the kind of humor that just permeates that whole society. I was taken by the way they would tell a story, the way they would cleverly bury their messages in these very humorous tales. So it was really in Canada I can say that I came to love and discover it.

Later on, I had this kind of reggae band in high school and university here. So we started experimenting, because I was listening to a lot about old-time calypso, and every time I’d go back to Trinidad a few times a year to see my father, he would take me to the calypso tents anytime I was there when they were open in the months before carnival. So I got to meet the Lord Kitchener and Mighty Bomber, Lord Funny and a lot of the great calypso artists, too many of whom are sadly no longer with us. I guess I fell in love with the music and started writing. It was a form that just came naturally to me.

Later on I moved to Toronto and hooked up with some Trinny ex-pat musicians, along with some members of my old band from Ottawa. We came together in the studio to record the first album, and the roll started from there.

I remember seeing you at WOMEX the first time you played there. How long ago was that?

Eleven years. 2010.

Wow. I'm starting to lose track of the decades at this point. But that's interesting. I have a couple of connections with Trinidad. We moved to Montréal in 1966, and my dad worked with a shipping company that was taking bauxite from Venezuela and Trinidad to make aluminum in Arvida up in the St. Lawrence River. That situation unraveled with the coming of container ships and the whole separatist struggle in Québec, but for a while we were quite connected with Trinidad. I went there when I was 11 years old, and I remember being serenaded by a wandering calypsonian. He just came up to the car we were in and started singing, improvising lyrics, telling my dad he looked like JFK and things like that.

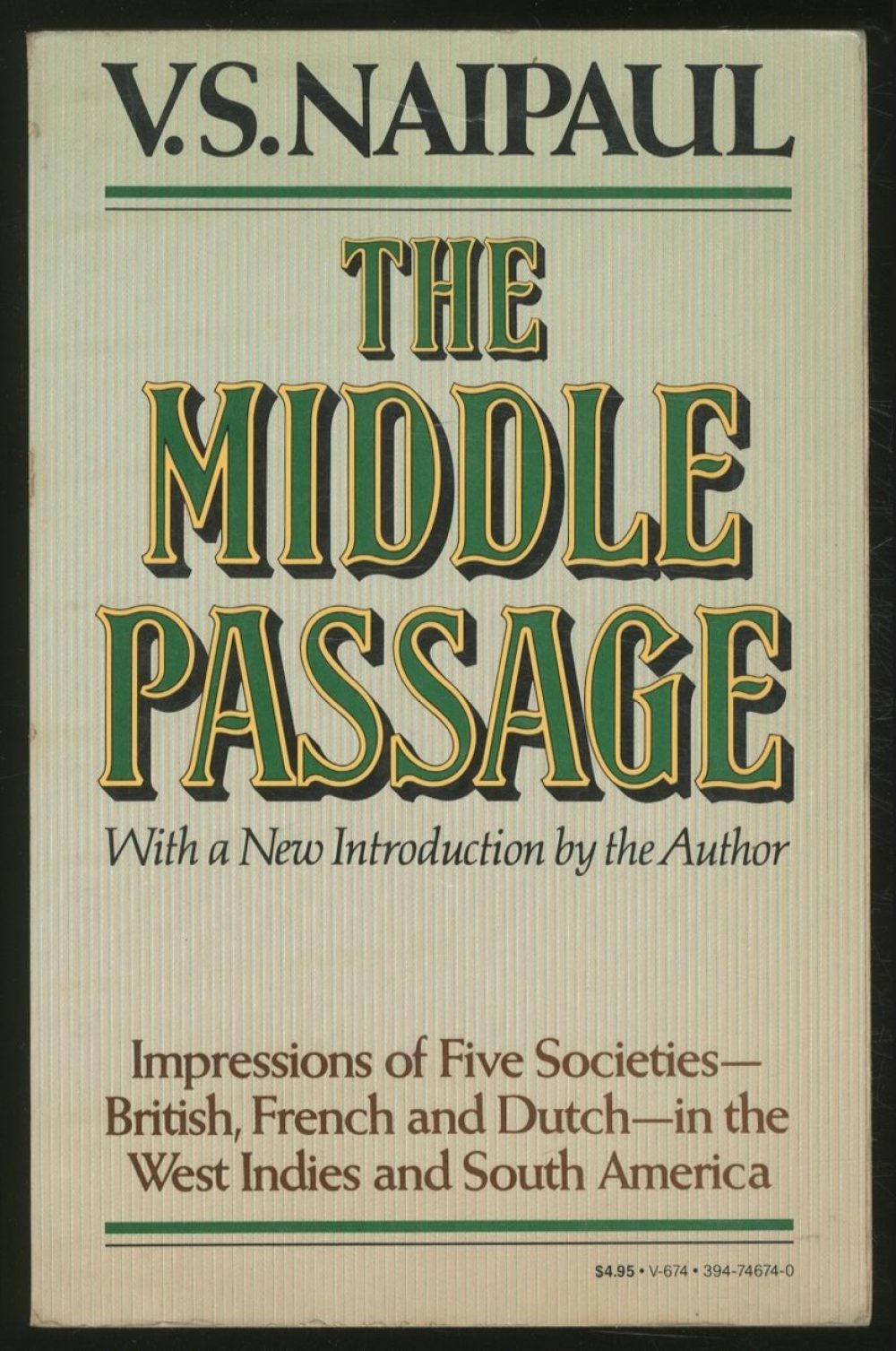

Then when I went to university, I ended up taking courses with the famous Trinidadian writer V.S. Naipaul.

Oh, wow.

And I got a completely different sense of things from that experience. I've never been back, but our show has certainly covered Trinidadian music and Trinidad’s carnival through other reporters and producers over the years. I'm curious to know what the scene is like in Toronto. I know that David Rudder was living there for awhile. Maybe he still does.

But is there a scene, a Trinidadian community scene?

Yeah, for sure. There is definitely a calypso scene in Toronto, quite a vibrant one. There are a lot of musicians from Trinidad and from other islands, like Roger Gibbs and Connector from Barbados. Every year up until very recently, they've had calypso tents, which of course for your audience I should explain is not a physical tent. Any venue where calypso is performed is called a tent, because in the earliest days they were bamboo tents. Those were the venues.

Now both in Trinidad and Toronto, they're more likely to be trade union halls where they have the shows. So, yeah, there's a lot of musicians there, and a lot of people keeping it quite alive with calypso and also other musics from Trinidad like parang, which is the Spanish Trinidadian music that they have a lot around Christmas time. The word parang is a corruption of paranda.

Right, the music the Garifunas play. Interesting.

Do you mind if I go back? Because you mentioned V.S. Naipaul.

Sure. I'd love to hear your thoughts about him.

His book The Middle Passage was a book that really shook me up as a teenager. I know that he acquired a lot of intellectual enemies in the Caribbean after he wrote that book, but he spoke a lot of the truths that are inconvenient and uncomfortable truths that we don't like to admit about ourselves. In reading through that book, and particularly the passage where he deals with his trip back to Trinidad, a trip that he always feared, it just rang so true to me from everything I observed growing up.

It's funny. I read that book in the interim between being in Canada and going back to Trinidad. So his words were sort of always in my mind and my ears. He was kind of my absentee tour guide back home. And I particularly loved his early novels.

Oh yes. Especially A House for Mister Biswas.

Yes. And Miguel Street.

Beautiful books. And it's interesting the way his own character evolved over the years. But that's interesting that his story of return affected you that way when you were young. Of course, he was never one to shy away from inconvenient truths. I've certainly met Trinidadians who do not look fondly on him at all.

Right. It's interesting. I used to always say that if an apple is half rotten, nobody will describe the rotten half as vividly as Naipaul.

So true. He had a special talent for that.

Let's talk about this album, Carnival of the Ghosts. Did you have any particular concept or ambition on this one?

I suppose this album is a bit of a departure in some ways, even though there's a lot of continuity, a lot of the same sources of inspiration musically. I think a lot of the previous albums have really had the Caribbean and its history at the forefront, especially the last one, Where The Galleon Sank. They were inspired by moments or places significant to the past that the Caribbean islands have come through. But this one I guess casts sort of a wider glance at human nature. I'm very aware now that we’re all rapidly becoming a part of it. so there's a feeling of impermanence that sort of hangs over a lot of the songs on this record. It's a bit of a wider look at the human condition, all our quirks and foibles—or as many as can be fit onto a 10-song record.

Well, you've packed a lot in. Let's talk about the title song. What's going on in that song

“Carnival of the Ghosts.” When I say this idea of mortality is in the whole record, each of the songs looks at it in a different way. This one looks at it in a sort of whimsical and humorous way. It's kind of a simple story. A guy is jumping up at carnival in Trinidad and he passes out, gets sick or whatever. He's inebriated and passes out, and then wakes up in the middle of the night to these empty, quiet streets, no one around. Then he hears a carnival band coming along in the distance. And when it approaches him, he is shocked to see that they are the spirits of the dead, and among those spirits are those of many famous historical people, Shah Jahan, the builder of the Taj Mahal, King Herod, Julius Caesar, Shaka Zulu… And each of them has something funny to say to him, either some general complaint about the human condition, or about life and the afterlife, or some parting word of advice. That's the story. It's kind of this dreamlike thing with this guy wandering the streets talking to the spirits of famous dead people.

Beautiful. Great story. What about “Down By the Water?”

That one again has the same theme. My godfather and my uncles were buried, or rather their ashes were placed in this bay called Scotland Bay on this little island between Trinidad and Venezuela where they had family cottage or cabin when they were growing up. It was a place beloved to them. So the image of the song is these ashes falling into the sunlit waves. It's kind of a song of hope, that someday we’ll be reunited again down by the water. As the old saying goes, “When the seas cough up the dead…”: So it seems like a heavy topic, but it's meant to be a joyous song, a song of hopeful expectation that people beloved to us will someday return to us.

O.K. This one may not be quite so hopeful, but tell me about "Hidden Hand."

[Laughs] I think that one of the things that hangs in the background of our culture, and is probably influenced by a lot of trains of thought, is the idea that we are somehow pawns in the hand of some impersonal force, forces that are ultimately beyond our control. It's been called many names at different times. So it's kind of a philosophical song about this entity behind things that kind of arranges the affairs of human beings, and in the face of which we seem to have no agency. So the "Hidden Hand" is meant to be somewhat satirical in that way.

That song struck me, because these days in this country we’re living in the wash of conspiracy theories where there's always some mysterious force manipulating everything behind the scenes. It's a very seductive but also dangerous mindset to fall into. Take the mythology surrounding COVID, the idea that they're putting microchips into the vaccines and this sort of thing. These are all hidden hands I suppose.

Yes. I guess. It's interesting. I find that’s one of those issues where it becomes like a marker for people on both sides, the tribal loyalties. You know one of the first casualties of conviction is always fair-mindedness. I've heard from people on both sides, those who have reasonable cases to be wary and skeptical, etc. But I guess in that song I'm thinking about this kind of deeper undercurrent.

Not so much a human hidden hand, but a more metaphysical one.

Yes. Or even the idea that history has this predetermined direction. Some people would've called that predestination. The Puritans might have called it that. I think we call it progress. It's the idea that things must go a certain way because they're foreordained. They must head in that direction, and in the midst of all that, we simply need to find our place floating down that stream. That's what I kind of take issue with in that song.

There are two songs I find interesting for their musical style, styles that are sort of adjacent to calypso as such. Start with “One By One,” which to me feels like a kind of minimalist ska. You can talk about the lyrics too, but I am curious about the music.

You know, I have to say, this whole ska thing happened after our Jumbie in the Jukebox record. I used to listen to old Jamaican ska, but people kept comparing us to the Specials or the English Beat, because there's a kind of a rock-ish vibe to our music. People would ask me about all these Specials songs in an interview like this, and I felt ashamed that I didn't know them. I think I pretended I knew the songs they were talking about. But then I went and listened to them and I really got into a lot of the British ska groups. And as happens with everything I listen to, that found its way into my music. And we have great horn players in the band.

You sure do. That was a highlight of your set at WOMEX, such a powerful brass section. That was really an awesome set, by the way.

Oh thanks, man. We had such a great time.

I could tell.

It was a joy just to play in front of people. You know the old cliché that you never miss anything until it's taken away from you. And that has been so, so true with our music. I think the time away has fundamentally changed the way I feel about it, in a good way. In a sense, you tour a lot for years and years, and you really take for granted this experience of meeting new people, making new friends, seeing interesting places, doing something that is so fulfilling all the time. And to be without it for a bit, I told myself at first, "I really don't miss it."

But the more time goes by…

Exactly. The first rehearsal back with the guys: we got together in this industrial area in Toronto where we do our rehearsing, and then I thought, “O.K., there is a void." It's the same way I don't miss Trinidad until I get off the plane and I look up at the green mountains. It was the same thing again with music. So nice. And so nice at WOMEX to have such a great, warm crowd.

We felt the same way, having set in this house for 18 months. The other song I wanted to ask you about style-wise is “Bournes Road.”

With that song I did something I had done with a previous song called “Abatina,” which is to take a refrain from an old-time calypso and then write a new song around it. So Bournes Road is actually a street in St. James, Trinidad. Our guitar player actually grew up on that street. The original song was an old sort of call-and -response chant by the Growling Tiger, back in the 1930s. So the song I wrote tells the story of a corrupt policeman who's used to throwing his power around and taking advantage of the people who are entrusted to his protection.

What about the music? It's not straight-up calypso.

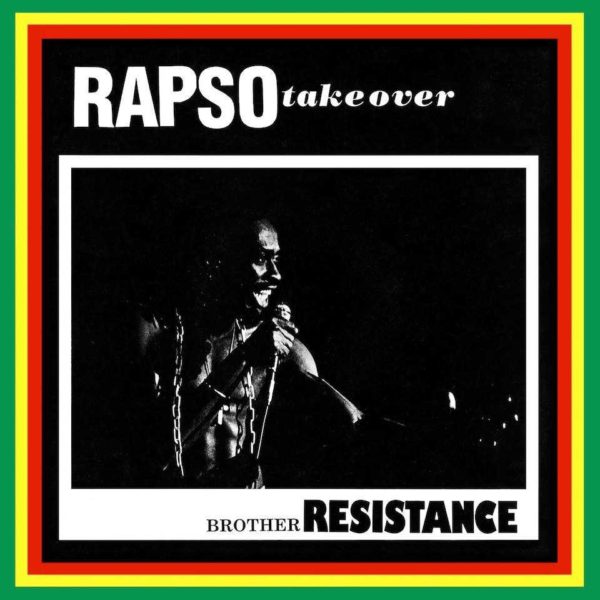

It's kind of like that old style, call-and-response. In Trinidad, they still refer to that as the kalenda style. It was a style that used to accompany stick fighting. So whenever you hear that kind of exchange between a group of singers and a singer, it harkens back to the days when the stick fighters would be fighting, and the groups from the neighborhood would meet in the streets of Trinidad. This was a big part of every carnival up until maybe a couple of decades ago. And now it's being revived.

But while the groups of stick fighters would face off with each other, one-on-one, there would be a person from each side called a chantwell who would get up and sing, boasting about the prowess of his own stick fighters, and he would taunt and mock the other side. When he would say something, the whole crowd would repeat it on their side. And the other side would say something, and the crowd would repeat it on their side. They would trade these insults. It was a long ago precursor to the rap battles of today.

That music over the years started to become more narrative in form, and very topical. And by the mid-1800s, you start getting songs about whoever was the then- governor of Trinidad. And over those long years, that turned into calypso.

Fascinating. I'm really looking forward to going back and listening to the album again now that you’ve given me all these insights. Tell me a little about your band. Has it changed much over the years, or has the personnel kept pretty steady?

It's been pretty steady. Everyone is involved in other projects, so it's a bit of a community. If somebody can't come for one particular show, there's somebody else who's part of the family as well. But on the whole, it's most of the same people.

The WOMEX set was a breakthrough for the band in terms of live performance. It's such a uncertain time now, but do you have plans for more touring? How are you approaching the situation?

I came back from WOMEX gleefully hopeful about the coming year. The reception was lovely and we got a lot of offers to perform all over the place. But we'll see how long the world stays open. These last couple of years, it has been impossible to look beyond the next few weeks really.

So difficult.

It's been a hard time for a lot of people to be isolated from their families too. I was lucky. I was actually up here because my sister my brother and my mother live here in the Ottawa area, so we were lucky to be close to each other in this sort of times.

One way or another, we all have to adjust to this, I suppose. But I look forward to things opening up. It would be great to see you down this way. Meanwhile, thanks so much for talking with me. I've been enjoying your music for years, so it's great to hear some of your story.

Wonderful to speak with you as well.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles