As fall rolls around, we’re seeing a flurry of interesting album launches. It’s as if everyone was waiting for the pandemic to end, and now, realizing that won’t be anytime soon, the attitude is: to hell with it; release the music! So once again, I find myself swimming through more music than any one person can fully absorb (not a bad place to be in a pandemic!). So here are eight standout titles from recent weeks that have proven very good company during the lockdown.

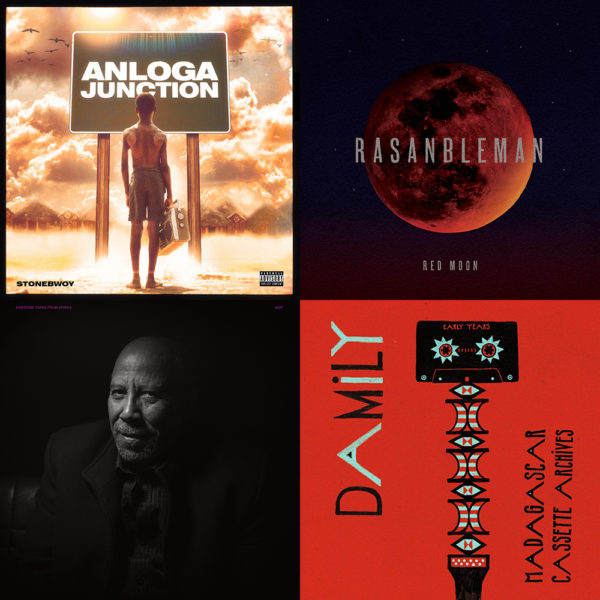

Bantu: Everybody Get Agenda (Soledad Productions)

Bantu is a wide-ranging, Lagos-based Afro-funk band that for years has stood strong for the art of live performance in an age of virtual and digital music. Since forming the group in 1996, tireless leader Ade Bantu has hosted the monthly Afropolitan Vibes showcase at Freedom Park, featuring an ever-changing cast of collaborators and co-stars. This release is a follow up to the band’s 2018 album, Agberos International, and it finds the band sounding better than ever in the studio. The brass is tight and feisty, the messages sharp with street-level savvy and the grooves… Well, what do you expect from folks raised on Fela’s Afrobeat? Titles like “Disrupt the Programme,” “Killers and Looters,” and “Big Lie” tell you right away that these are not songs about young love, fashion and aspirational wealth. Bantu carries the torch for ecstatic, socially engaged, big-band Afrobeat as any group out there. “Water Cemetary” has the slinky tunefulness of a soul ballad, and there’s plenty of cool jazz in the arrangements, but mostly this is a work of unbridled, funky passion. Highly recommended.

Nation Beat: The Royal Chase (Fresh Grass)

Over the past decade or so, Nation Beat has evolved steadily, while always holding on to an enduringly original concept: connecting the rhythms and melodies of northeast Brazil with those of the Mississippi Delta. The parallax between these two hinterlands of the Afro-Indigenous-European New World are not so much analyzed as felt. The music speaks. The band’s latest incarnation is almost entirely instrumental, a funky, swinging brass band powered by the extraordinary drumming and percussion of founder and bandleader Scott Kettner. This collection of tunes grew out of Kettner’s urge to reimagine rural, rowdy Brazilian forró music—once famously described as “music for maids and taxi drivers”—as jazz. These expansive arrangements make room for free-flowing improvisation by the players—Kettner plus four horn players, including sousaphone bass—awesome. We get some terrific guest vocals, as on the Nawlins classic “Hey Pocky Way (Featuring Moses Patrou),” here supercharged with Brazilian maracatu rhythm. Forró is naturally joyous music, and in the hands of this ensemble it simply bursts. Spend three minutes listening to their take on Luiz Gonzaga’s “Forró No Escuro,” and your spirits are guaranteed to soar out of their pandemic funk. Earl King’s “Big Chief,” with its spiraling, irresistible hook melody also gets a giddy, backbeat-heavy makeover.

Songhoy Blues: Optimisme (Fat Possum)

For an album about optimism, this release sure kicks with righteous fury! These four lads from Gao in northeast Mali met as students in Bamako and rocketed to international success in part through their starring role in the superb 2015 documentary film, They Will Have to Kill Us First. They surf the interface between Malian pentatonic boogie and hard-core rock with a new level of sophistication and power, and when combined with the tough lyrics here, the effect is riveting. Whether expressing punk defiance—"Badala (Don’t Give a S %&*)”—celebrating rebel heroes of the past—“Assadja (Heroes)”—or pledging blood to keep Mali unified in the face of recent conflicts—“Fey Fey (Division)”—this band puts muscle behind its messages. Aliou Touré’s vocals cut through the rollicking roar with new authority; clearly these guys have picked up some production tips from their pals in international rock. And Garba Touré is simply one of the most fluid and exciting electric guitarists in Mali today—and that is saying something. His pointillistic vamps are deep and funky, and when he lets loose on a solo, look out! But more than anything, it’s the sense of urgency behind messages here about the perils of fleeing to Europe, the pain of arranged marriage, and the deep desire of Malians for good governance, that make this such an outstanding album. Very smart move to include lyric translations.

Qwanqwa: Volume 3 (Self-produced)

This five-piece Ethiopian neo-traditional ensemble was founded in Addis Ababa in 2012 by American violinist Kaethe Hostetter, who first traveled to Ethiopia as a member of the acclaimed Boston-based Debo Band. Hostetter subsequently moved to Addis and recruited some of the city’s top instrumentalists, initially to create an adventurous string band with mesenko (one-stringed fiddle), krar (electric lyre), bass krar, kebero (goat-skin drum) and her own five-string electric fiddle. Their third release is the first to be widely available internationally, and its music also ventures beyond Ethiopian traditions to include a Somali pop song and an Eritrean folk song. The album launches with a perky violin feature, “Ago,” in which Hostetter borrows a melody from a northern shepherd’s flute. “Sewooch” is a terrific take on Addis funk, paying homage to the 1970s greats, but with the jangle of folklore and gutsy vocals from Salemne. The band cooks with spare, snappy grooves grounded in percussion but rich with melodies. On “Somali”—a cover of a song by Somalia’s legendary Dur Dur Band—Hostetter’s violin gets processed into a retro-techo warble that rides joyously over tumbling percussion. The set ends with a 17-plus minute “Wedding Song,” really a suite of songs featuring strong Amharic vocals from krar player Mesele Asmamaw. The feel starts slowly with rhythmic hand clapping, and builds through thrilling peaks into cool vamp valleys. Asmamaw’s wheedling masenko at times joins Hostetter’s violin in unison to great effect. The trance ebbs and flows and, ultimately, fades off into the distance. This album was recorded amid rising political turmoil in Ethiopia and finished in time for a 2020 tour that was not to be, all of which makes its arrival that much more welcome.

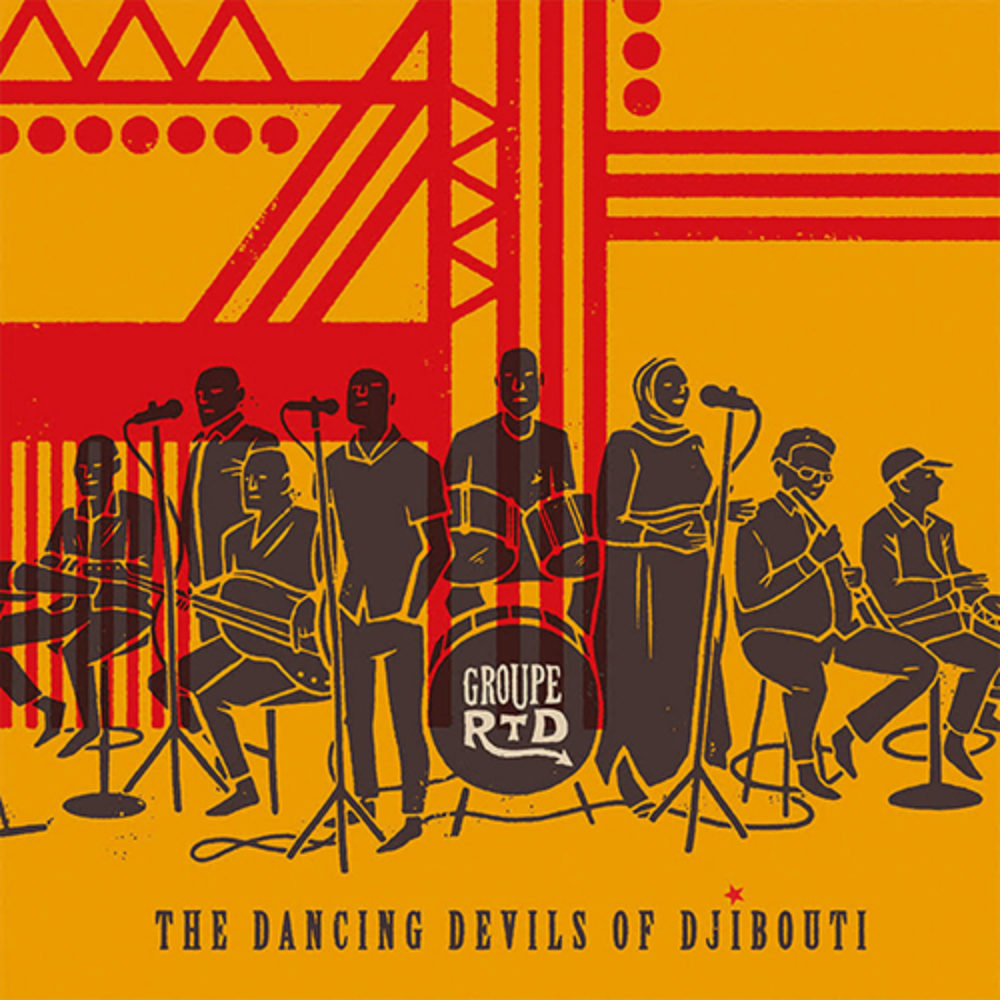

Groupe RTD: The Dancing Devils of Djibouti (Ostinato)

While we’re on the East Africa tip, here’s a story for the ages. Ostinato Records managed to work through layers of governmental secrecy and red tape to make the first international recording of Djibouti’s state band, Groupe RTD (Radiodiffusion-Télévision Djibouti). Since independence in 1977, Djibouti’s strict regime has turned music into a state enterprise and keeps a tight lid on it. This project lifts the veil just enough to leave us hungry for more. After tricky negotiations and the importation of a mobile studio, the recordists and musicians gathered in the state radio studio for a “heated, three-day, khat-fueled devilish feast of music amid a smokey haze.” And you feel all of that in these rocking tracks. There are echoes of bebop jazz, funk, soul, reggae, and Somali and Bollywood pop, but the music is firmly rooted in East Africa’s rollicking grooves and pentatonic melodies. It’s an irresistible stew. Spectacular solo vocalists—both male and female—belt out unforgettable hook melodies, backed by soaring organ and saxophone riffs, gritty electric guitar vamps, and a rhythm section with a visceral life force. From the brassy opening notes to the traditional, a cappella closer, there is urgency in this music that commands instant attention and never lets go. This album has been in my “new music” playlist for months. I can’t get enough of it.

Awale Jant Band: Yewoulen: Wake Up (Arc Music)

Here’s a highly satisfying merger of Afrobeat, jazz and Senegalese folklore. This eight-piece combo is actually a combination of two bands: London-based French guitarist Thibault Remi’s multinational Awale, and Senegalese vocalist Biram Seck’s Jant Band. Thibault is a skilled composer/arranger clearly versed in a variety of styles. Seck is the son of a gawlo (Wolof griot), and that shows in his commanding leads, often evocative of the top mbalax stars. But the grooves here range far from the Wolof sabar percussion at that genre’s heart. Drum vamps on Afrobeat-oriented tunes like “Sope” and “Domi Adama” nod strongly to Tony Allen’s signature shuffle. “Just be Free” feels more like Memphis soul. “Jeunesse” (“Youth”) merges Afrobeat with New Orleans backbeat funk. Other grooves are harder to pigeonhole, but they never feel forced. The brass shows similar versatility, soft and funereal on “Jules,” a remembrance of a lost friend, breaking out in thrilling solos, popping in with jazzy fills in all sorts of voicings, and of course, rising to full-on Afrobeat blare at just the right moments. Fusion is a tricky art that can easily yield confusion and stylistic chaos. Not here. Despite dazzling diversity, these influences fit together seamlessly, buoyed by excellent musicianship all around.

Ayom: Ayom (Amplifica)

Here’s another fusion that works, and I think I know why. On their debut album, this six-piece combo out of Barcelona showcases a liquid-voiced Brazilian vocalist, Jabu Morales, who also plays traditional Brazilian percussion. But her band members hail from Angola, Italy and Greece, and the music they play draws broadly from the Afro-Lusophone world—Brazil, Angola, Cape Verde—accented with Mediterranean flavors, such as Alberto Becucci’s accordion. It doesn’t matter whether you can’t hear the difference between funaná, carimbó, cumbia, baiào or semba; what you can’t miss is that each of these 11 delightful tracks has a character all its own. What ties them together is the Lusaphone connection. Languages, rhythms and sonorities comingle with ease, because they are wound together with the threads of Portuguese seafaring (not to mention colonizing) history. Of course, it also matters that these musicians have clearly bonded deeply around a shared vision. There are too many standout tunes to unpack, but as an example, “Baile das Catitas” opens with a triangle that evokes northeastern Brazil’s forró, but Ricardo Quinteira’s electric guitar ostinato feels more like surf music, and then comes the thundering surdo drum backbone and a deep, fat-toned accordion intervention. When the snare drum kicks in, we’re back to racing forró, and Morales sings a spitfire melody processed to sound like it’s coming out of a transistor radio. And that’s just the first 90 seconds. It’s a surprise a minute on this album. If this band sounds this good live, they’re going to positively slay in the post-pandemic touring circuit.

Fra Fra: Funeral Songs (Glitterbeat)

Here’s another hidden marvel captured in situ by maverick producer Ian Brennan (of Zimba Prison Project fame, among many others). This time, Brennan’s microphones capture hypnotic funeral songs performed by a small men’s ensemble on the outskirts of Tamale in northern Ghana. Fra Fra is a name colonizers gave to their ethnic group, and the musicians’ decision to embrace it tells you something about their attitude toward authenticity—as if to say, “Call us whatever the hell you want, but remember, you can’t escape death!” “You Can’t Escape Death” is literally one of the song titles, along with such cheery sentiments as “Goodbye, “We Must Grieve Together,” and “Naked (You Enter & Leave This World with Nothing).” That said, the music is anything but dreary. Its call-and-response vocals between a gravel-voiced blues shouter and a unison male chorus. The backing is spare: hand-clapping and the dull thud of a “two string ‘guitar’ with dog-tags fastened at the head as rattles.” Tempos range from march speed—after all, this processional music—to frantic. Raw sound, beautifully recorded, and strangely transporting, these are songs of collective grieving, not with sentimentality and tears, but with praise, wisdom and courage.