Joseph Braude is the author of The New Iraq (Basic Books, 2003) and other books. At the time this interview took place, he wrote a column for The New Republic on arts, culture, and politics in the Middle East. Fluent in Arabic, Hebrew, and Farsi (Persian), he studied Near Eastern languages and literature at Yale and Arabic and Islamic History at Princeton, and has resided in Egypt, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates as an academic fellow. During his residence at Dubai’s Jum’a ‘l-Majid Center for Culture and Heritage, a library and museum of Gulf culture, he studied the unique intersection of African and Asian cultural influences in the music and poetry of the Arabian Gulf. Braude is also a semi-professional oud player who enjoys sitting in with local bands during his frequent visits to the Middle East.

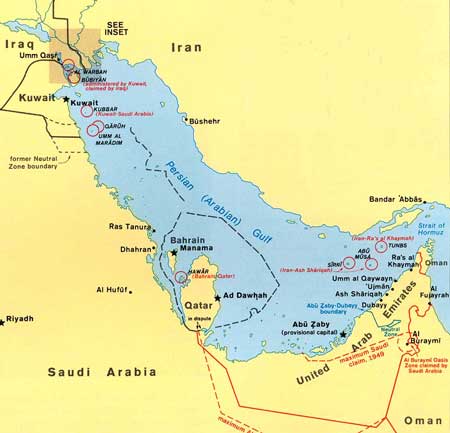

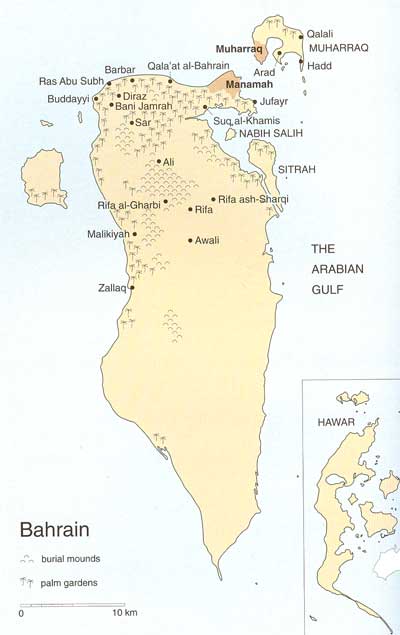

Banning Eyre interviewed Joseph Braude in May 2006 for the program African Slaves in Islamic Lands, and again in February, 2007 for the program Africans in the Arabian Gulf. In between those two interviews, Braude made an extensive research trip to the Gulf, interviewing authorities on Gulf (Khaliji) music, Dr. Bandar Ubayd in Kuwait and Ahmed al-Jumayri in Bahrain. Braude also explored the private world of Sudanese Sufis in Qatar. What follows is an amalgam of excerpts from all of these interviews. Some of the images here come from a remarkable book, “Music in Bahrain: Traditional Music of the Arabian Gulf” (Jutland Archaeological Society, 2002) by Poul Rovsing Olsen. Also a point of terminology. The speakers in this feature refer to the “Arabian Gulf.” This is the same body of water that is officially known as the “Persian Gulf.”

Banning Eyre: Joseph, to begin with, tell us a bit about yourself and how it is that you came to spend time in the Arabian Gulf.

Joseph Braude.: I've had a personal affinity for the Gulf in part because Gulf culture is profoundly influenced by Iraqi culture, and my mother is originally from Baghdad. I come from an Iraqi Jewish family, and so for many years, people like me weren't able to enter Iraq. Back when I was a student and grad student of Arabic and Islamic studies, I never turned down an opportunity to visit the Gulf states in Iraq’s periphery. I spent time in their manuscript archives where Iraqi expats and local scholars teamed up in intellectual and cultural pursuit. It was a great way, through learning and friendships, to come as close as I could to the dialect, the music, and the sensibilities of the culture my mom’s family hailed from. I lived in the United Arab Emirates in 1999, and that was the first time I spent a significant period of time in the Gulf region, but I've continued to visit numerous Gulf states since then.

B.E: Let’s start with the basics. What should Americans know about the countries of the Arabian Gulf?

J.B: As nation states, the Arabian Gulf countries are very young. Bahrain, for example, was born in 1973, out of independence from British colonialism. And the UAE, United Arab Emirates, also dates back just to the early 1970s as a sovereign state with a seat at the UN. There are six countries in the Arabian Gulf, and if you go back a hundred years, there were none. That doesn’t mean that there wasn’t leadership and political organization. In fact, there is some continuity between the leadership of the Arabian Gulf today and patriarchal arrangements dating back three centuries. Tribes that are now ruling families in Bahrain, Dubai, Sharjah, and Riyadh were in control of those areas long before the advent of nationalism.. Clans and tribal confederations became political leaders, and as they emerged into the light of nationalism and sovereignty, the tribal organization of politics and culture was grafted onto the state system. Many of those old tribal names are now royal names as these areas developed into Emirates, under the rule of an Emir.

B.E: What is the ethnic makeup of these countries? They are not entirely Arab, are they?

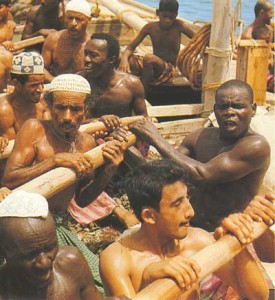

J.B: The Arabian Gulf states came on the map in the international stage with the discovery of oil. Long before that, they were on the map in the regional stage, beginning with the distinguished place of Mecca and Medina as two religious capitals of the Muslim world. As urban centers of profane culture, Gulf towns were largely backwaters. That said, they were also melting pots of culture. Indigenous Bedouin of the Arabian Gulf met surrounding influences from what were, way back when, political and cultural powerhouses, like Iran, India, Mesopotamia, and the countries of East Africa. People came, whether it be through slavery, through trade, through a variety of other contexts. They made their way into the Gulf, and they brought their languages, their cultures, and their music. African history is intertwined with the history of the Arabian Gulf going back centuries. It wasn’t always a happy mix. 300 years ago, most of the Africans who arrived on the Arabian Gulf Shores came as slaves. They weren’t all slaves. Some of them came as workers who staffed the boats that brought merchandise across the borders of the Arabian Gulf to and from Ethiopia and India and other parts of that region.

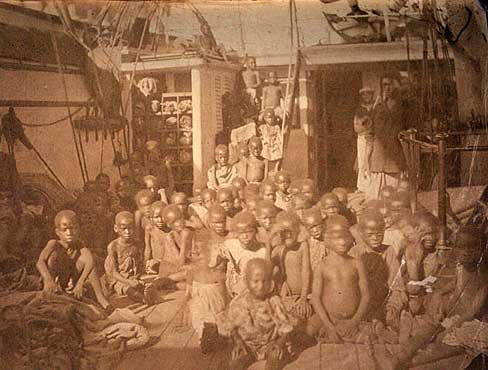

African Slaves on the Indian Ocean Passage, 1868

B.E: How did African slavery play out in the Gulf states?

J.B.: Well, first of all, slavery in the Middle East and North Africa predates Islam. It predates the Arab invasions of those regions after Islam's birth in Arabia. Islam has kind of an ambivalent attitude toward slavery. It does not ban it, but it attempts to regulate it in certain ways, and it also introduces gradations of slavery. For example, the Jewish and Christian slave has a status that is superior to that of the pagan slave, and Muslims, if indentured or enslaved through circumstances, have a status that is superior to the Jewish or Christian slave. So these are innovations that certainly helped some slaves live better lives, but also are a far cry from anything approaching an abolitionist movement. The 9th century Iraqi writer Al-Jahiz wrote a great deal about slaves. He has a book about singing girl slaves, who were indentured for purposes of sex and entertainment. He expresses views on what different colored slaves are good for and not good for, and he introduces what would be, in modern terms, stereotypes of different racial and ethnic groups.

The most obvious example is that there was widespread belief that Turkish slaves made good soldiers, and the Abbasid caliphate, which ruled from Baghdad and elsewhere for much of 500 years, made prolific use of Turks as slave troops for their army. On the other hand, slaves from East Africa, who were brought in along the Nile and up the coast of East Africa and into the Arabian Gulf and what is now southern Iraq, were the engines of infrastructure development in southern Iraq for a time, and they also were the human resources for what was the only plantation economy in the history of the Middle East. They revolted, not once or twice, but three times during the Abbasid period. The third and final so-called Zanj Revolt lasted for about 14 years, and it was a major, cataclysmic event in the history of the Abbasid Empire.

One of the changes that happens over time is a change to origins of the slaves brought to the Arabian Gulf. For starters, you have the phenomenon of resistance, like the Zanj Revolt, and then you have conversion to Islam by Africans along the Indian Ocean coast, and it becomes more difficult to enslave Muslims over time, as notions of equity and egalitarianism within the Islamic polity become stronger. So it becomes necessary for Muslim slave traders to reach deeper into Africa, beyond the Indian Ocean coast, into places like Malawi, Zambia, southern Sudan, the eastern part of what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. So there is this change in the origin of slaves across the centuries, for one thing.

African Slaves on the Indian Ocean Passage, 1868

B.E: Ronald Segal’s book Islam’s Black Slaves describes a bloom of slave capturing in the 19th century. He calls it "the terrible century." I'm wondering if this has something to do with what they call scramble for Africa, the intensely competitive struggle French, British, and other foreign interests to lay claim to African territory during that time.

J.B.: Yes. I think that that is correct. I would hesitate to apply that to the Gulf, though, which at that time was a political backwater, and was not really scrambling in any serious sense. They were not mobilizing. This is the pre-oil Gulf.

B.E: Okay. But if we think of that period, say the late 19th century, how many of those Africans that passed through Zanzibar or other East Africa ports wound up in the Gulf?

J.B.: I would suspect that one crucial distinction could be drawn between Iraq at that time, which was an Ottoman province, and portions of the Gulf, which had relations in the 19th century with Great Britain. What is now the United Arab Emirates, the ports of Dubai and Abu Dhabi for example, Bahrain, were becoming protectorates. So I would guess that there was a significant inflow of slaves to the Gulf at that time. There certainly were slaveholding states. So that would not surprise me.

B.E: And how is the legacy of Africa visible in the Gulf today?

J.B.: This is not a topic that is celebrated or widely discussed within the discourses of these countries. If you challenge someone and ask them, they will generally say, "Yeah, my ancestors came from Africa." Even princes. If you go to Saudi Arabia, Prince Bandar, who was for many years the Ambassador of Saudi Arabia to Washington, will tell you that he has African origins by way of his mother. This is probably is the result of extensive intermarriage between African slaves, former slaves, progeny of former slaves, and to the royal family of the Saud clan. Slavery in Saudi Arabia was not banned until 1962, but to this day you really feel Africa when you walk the streets of Jeddah or Riyadh, and see so many people who have African features.

Another thing that is common in Saudi Arabia is that African ethnic Saudi nationals often are recruited by the family of a Prince to become part of that prince’s retinue. They essentially are born and grow up with the family, and are the contemporaries of the young Prince. They know him from a young age. They play together. And then as they grow up together, it is made clear that this young boy is a Prince, and these young boys around him are his retinue, his so-called "brothers." Now, the term "brother" is a term of endearment, not a denotation of a blood tie. They are salaried, security and constant companions of many princes. And so it is somewhat common in Saudi Arabia, a country with thousands of princes, to find in a five-star hotel, a very wealthy person pulling up in a really fancy car, who has lighter features, lighter complexion, surrounded by eight or nine darker complexioned people, all turbaned, all similarly dressed, all speaking the same Saudi dialect of Arabic. One is a prince, and 8 or 9 are his retinue, and they tend to be of African stock.

B. E: Fascinating. When you do talk to people about this, I'm curious as to how specific they can be about African origins. Is it just a general idea that they carry with them, or can they fill it out with detail? For example, can you distinguish people who descend from freed slaves as opposed to those who have come as workers in more recent waves of African immigration?

J.B.: Well, one interesting indicator of that is names. You have people who are identifying themselves as affixed to tribes. They have Bedouin tribal names, and in some ways this parallels the way that, for example, a slave in the United States would have the name of the family that owned him. Washington. Jefferson. These are the names of African Americans today. They reflect the fact that their origins were those slave-holding families. You have similar relationships and nomenclature in the Gulf, names that I heard and asked people about, who were obviously of African stock. I'd say, "This is obviously a Nejdi Tribal name, and yet you would appear to be not have Bedouin origin, but of African origin, or some combination." So he would say, "No, my family goes back a long way as clients of that tribe.” “Clients” denotes a range of relationships to a patriarchy that has included slaves and indentured servants. So I'm certain that that could have happened in the 19th century, but it also could have happened much earlier as well.

In general—and this is a broad generalization—I think it is fair to say that in the Gulf, in Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Kuwait, a large number of African ethnics who are nationals in those countries are lower on the socioeconomic ladder. That said, there are notable exceptions, including senior people in politics and government in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere. When you have conversations with Gulf nationals of African origin, they are not necessarily acculturated to welcoming discussions of family genealogy and African roots, or asking the sorts of questions that might help situate their particular family history in the context of broader histories of cultures and peoples in Africa. So it is not necessarily common to find people who'll wax poetic on their family origin, and their odyssey from Africa, and in some circles it's kind of a taboo topic as well. People don't like to dwell on the slave history of the country.

B.E: We will come back to the whole question of African identity when we get into the music, but first an important bit of Gulf history. What was the impact of the discovery of oil in the Arabian Gulf?

J.B: Oil discoveries happened in the early 20th century throughout the Gulf states. These discoveries transformed the economies and the cultures of the Gulf. Before the discovery of oil, most of the new arrivals in the Gulf came from the neighborhood, from India, Iran, and East African countries. After the discovery of oil, people came from all over the world, from Europe, from North and South America, from elsewhere, as workers, as advisors for oil companies, as builders of secondary industries, construction, and the economy overall. They brought with them their culture, and you can even hear that in the music. When you hear the electric guitar, and a western melody on a Gulf album, you know that’s the sound of oil. If not for the discovery of oil, there would probably be no band in Kuwait called Miami.

B.E: What is khaliji?

J.B: Khaliji music means “Gulf music,” and that is a new expression used to describe all the musical sounds from all the Arabian Gulf countries. If you had talked to a guy 50 years ago, he didn’t have that idea of a Gulf identity, a Gulf consciousness. That comes with the political sovereignty that these countries developed. It comes with the marketing of a type of music that melded through regional collaborations into a coherent sound. If we break up khaliji music, Gulf music, into its component parts, we hear strains from Africa and India and Iran, and all kinds of indigenous Bedouin sounds that date way back before nation states and oil.

Khaliji CD

Khaliji is very different from what people listen to in the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa. Sometimes, the Gulf music uses a pentatonic scale, which I always associate with having African origins, ancient origins—the nexus of ancient Egypt and Nubia and the African continent. Another thing is the rhythms themselves, which differ from the baladi rhythm of Egypt, and other eastern Mediterranean rhythms. The 6- and 12-beat rhythms that you hear in Gulf music are not your standard Arabic rhythms. Go to a country like Lebanon and you hear a lot of 4-beat stuff in their classical music. There is interesting 7- and 13-beat stuff. But the 6/8 and the 12/8 has a special African sound that comes from that unique relationship between East Africa and the Arabian Gulf.

Also, Eastern Mediterranean, Arab styles in the 19th and 20th centuries were profoundly influenced by Western music. The Gulf during much of that period did not intermingle to the same extent with orchestrations along the western style, and western scales and western rhythms. It maintained a greater affinity with rural folkloric roots, and I'm talking about the music of the elites in the Gulf. There was a closer intimacy with the rural, folkloric, Bedouin roots.

Pearl Divers in Bahrain

Songs of the Pearl Divers

[Khaliji music encompasses traditional folkloric music—with its blend of Bedouin, Persian, Indian and African elements—as well as classical forms such as mawwal and sawt, and now electric pop music. Starting with the folkloric realm, one of the most fascinating genres is pearl diving songs. Pearl diving songs are found in Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and Abu Dhabi, but Bahrain is center of the diving and the songs. Once the island nation’s most important industry, diving was in decline even before oil was discovered in 1932. Bahrain had 1500 pearl diving boats in 1833, just 340 in 1934. But before that, tradition seems to go back some 4000 years. Pearl divers included Africans (originally slaves) as well as Indians and Sri Lankans. And that complex legacy is audible in the powerful, hypnotic music that survives today.]

J.B.: Diving for pearls probably sounds a little obscure, or exotic today. But if you think back to before the discovery of oil, it was the number one industry in the Arabian Gulf. That, aside from gold smuggling, was king. Pearl diving as an industry barely survives in the Gulf. They have been upstaged by cheaper labor in places like the Philippines and even Japan. What does survive from that industry is the musical organization of the workers into a chorus of 35 or 40 men who used a full boat, and every crew has its one or two nahhams, those semi professional singers who led the singing. So they may no longer board a ship, but those nahhams are now prized preservationist artists who sing into microphones in the Gulf Folklore Center in Qatar, and all over the region.

There is still a bit of pearl diving happening in Bahrain today, largely by subcontinent tenant Filipino and Bangladeshi workers. They are fitted with equipment that makes it a much more tolerable job. But in the past, this was very dangerous work. The bens would be common among pearl divers, because all they would be doing would be holding a heavy stone, and going straight down. This was really, really dangerous. So the songs have this sort of inspirational component to them. They embolden you, and you sing them for hours at a time. They’re also very beautiful and unusual.

B.E: It seems there are many varieties of Pearl diving songs.

J.B: It's an entire genre with songs for all occasions in the lifecycle of the pearl diver. There are songs for when there's a ferocious wind storm that rocks the boat back and forth. The song helps the pearl divers feel less afraid. There are songs for the wives of the pearl divers, singing about their longing for their husbands, waiting for them to come back from the city. There are even songs with drumroll and fanfare for when the Emir, the Prince, sends off the pearl divers to bring back their treasures, and slaughters a sheep or two for spittle grilling on the beach, a kind of a barbecue in their honor before they go out to sea.

B.E: And there is an African component to them, because many of these workers were Africans, right?

J.B: Yes. Many of the pearl divers were Africans, and they would sing these chants, and also the Arabic that they would sing is a little different. It is not easy for a modern Arabic speaker to understand, and I think that it represents an African component. It's a little bit of a pitch in to some degree, which again would strengthen the idea of a 19th-century presence. Because of their incorporating elements from different languages, the chances are that they are relatively recent arrivals.

Bahrainis of African origin all speak Arabic, and their dialect is not very different from Bahrainis of Bedouin origin. But if you go back even to the 40s you are going to hear songs that were sung by those African Bahrainis in Swahili. Some of those songs still survive and a few of the refrains are still familiar to Bahrainis who don't remember even a trace of the original African language. It's sort of the equivalent of the American song “Aiko Aiko,” which comes from an old African language and has been built into an American pop song by people who no longer remember what it used to mean.

B.E: Poul Rovsing Olsen, the Danish musicologist writes about a “black community" in Bahrain in the 1970s. Is that an operative concept today?

J.B: Western scholars who used to come to Bahrain in the 70s and study the musical culture of the place used to try to look at the people of Bahrain through the prism of a "black community" and a "white community." But when you look at the way Bahrain’s people talk about themselves, they don't really parse it that way. There are no journals of African Bahraini studies. There are no black community associations of Bahraini nationals. That said, there is an awareness of African roots in Bahrain's identity, and there is pride on the part of Bahrainis in pointing out that some of the ministers in Bahrain's cabinet today are of African origin.

Even though lots of Gulf nationals are of African stock, it is uncommon for them to celebrate their African heritage. It is a culture that still regards the history of slavery as taboo, off-limits, not something that should be broadly examined. The Gulf is a place where African and Arab culture have been intermingling for 700 years. The Eastern Mediterranean is a place where Hellenic and Byzantine and Arab culture have been intermingling for 1500 years, and that is kind of the way it breaks down. Sometimes Arabs in Eastern Mediterranean deride the African origins of people and culture in the Gulf. So the Gulf music is unfortunately looked down upon in countries like Lebanon and Egypt. It is not typically popular with Egyptian and Lebanese youth the way that Egyptian and Lebanese music are enjoyed by Gulf Arabs.

When Arab nationals to the west of the Gulf and north of the Gulf deride the Gulf states, they sometimes use racial epithets that are eerily similar to Western derision of African Americans, and other Africans. For example, I recall on the floor of the Arab League summit in the tense lead up to the Iraq war when Izzat Duri, who was the representative of the Iraqi government, was angry at the Kuwaiti Foreign Ministry, he called the Kuwaiti Foreign Minister “a monkey.” The use of terms like monkeys and apes as terms of derision for Arabs on the Gulf are a very common form of derision when derision is called for in Lebanon, Egypt, and elsewhere. And there is this understanding that there is some kind of a connection to the African, ethnic features, and those racist words that are sometimes used to describe them.

This resentment has to be contextualized in the phenomenon of the discovery of oil, and the sudden wealth and sudden power and sudden profligate spending, and at times, lascivious behavior of the Gulf Arabs empowered by oil wealth and coming to Egypt and Lebanon, the capitals of entertainment in the Middle East. There is sort of the sense that the tables have turned radically and inexplicably, so that what was once a cultural backwater is now the economic powerhouse, and what were once the cultural and intellectual capitals of the Middle East and the Muslim world are suddenly playing service industry to these petrodollar-rich individuals. So in that context, the resentment comes out, and sometimes, the resentment takes on a racist component.

Kuwait

B.E: That’s a great overview, Joseph. I want to hear about some of your adventures on your recent travels through the Arabian Gulf. Tell us about meeting Dr. Bandar Ubayd in Kuwait.

Bandar Ubayd in Kuwait (Braude-2006)

J.B: Well, if you want to know about Khaliji music, you have to go to the source. In the whole Gulf region, there is only one standing music conservatory, stuck between a chicken rotisa-mat and an Islamic charitable trust, in a coastal suburb of Kuwait City. It’s a quiet, unassuming building. You walk through a courtyard, and you see men in the white dishdashas and women veiled, clutching their instruments a little uneasily on a Sunday afternoon. It was exam day, the end of the semester and the dean, Dr. Bandar Ubayd was about to find out just how much they knew about Gulf music. I walked into the dean’s office, and Dr. Bandar was ready with his oud. He’s turbaned. He’s mustached, and he’s 6 feet tall, and he’s got all these friends hanging around with him, and they’re singing, they’re riffing on their own ouds. Some of them are students. Some of them are players in his band, and he has his oud, always ready to break it out and offer a musical example to illustrate a point that he’s making in conversation, or in a climactic moment in a story that he wants to tell. That’s the musical culture in this conservatory.

Bandar Ubayd: Khaliji music has roots going back more than 1000 years, to the Islamic period, Umayyad Abbasid. In the Abbasid period, arts in general flourished, and spread all over the region that was close to Mecca. We found that the Kuwaiti sawt (a semi-classical song form) has roots going back to the Abbasid period, and there are historical proofs supporting that from Kitab Al-Aghani of Isfahani.

There is also an Indian influence, going back to Abdullah al-Faraj, who died 1901. He had lived in India for 40-50 years, and his journey is known. He went with his father in the 1800s, as merchants. And India at that time had great arts. He spent the wealth that he inherited, several thousand dinars to study music and arts. He would meet with Arab émigrés in India who had come from Yemen, and took from them many arts, and he eventually decided to come home to his family home. His family was there, but the man, having now money, sat in his house and brought the first oud ever to Kuwait and perhaps to the Gulf. He was a poet and painter and composer and oud player. He had a group around him who were considered his students. They did it secretly, because art at that time was forbidden. He sat at his late father’s house, got a group around him that became his students, and taught his arts. And much voice, arts and melodies are attributed to him. In addition to some light songs. Those who learned from him included Yusuf al-Bakr, Mahmoud al-Kuwaiti, Abd al-Latif al-Kuwaiti, and others. The roots of this music extend all the way to the present. Many say that al-Faraj is the founder of Khaliji music, and from Kuwait the arts spread to throughout the Gulf.

B.E: Joseph, Dr. Bandar tells you that al-Faraj was the founder of khaliji music. What you make of that?

J.B: Maybe he’s right. It certainly shows how proud he is of the Kuwaiti role in developing and maturing the music of the Gulf. But I will say that in traveling throughout the Gulf that I met many people who said that a local from their neighborhood was the founder of Gulf music. That shows us something universal about human nature, that we learn from the cultures around us and we come to love what we learned so much that we begin to claim it as our own.

Bandar Ubayd, on the African roots of Khaliji music: There’s another type of arts in Kuwait called Bahriyya arts – arts of the sea – especially in the maritime season, and the arts of journeying, visiting from places, practicing trade, and in the course of these journeys that usually took a year’s time round trip, and arts were practiced during these journeys, arts of travel. Some of the arts were shared – light arts – which they called Uns. There are special Ghos [diving] arts, special to those who went on a boat, and there is palm clapping [as in many pearl divivng songs.] There is a nahham – songs of longing to see family, memorial, and very connected also with religion, asking God to return them home safely. When you hear it, it moves you with love and longing. These are some of the Bahri songs.

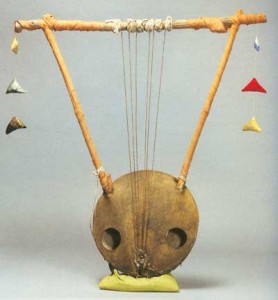

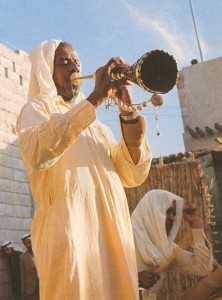

Leiwa ritual in Bahrain

We also have a form of songs called the Mustawtana arts – i.e., arts that settled in Kuwait and are not rooted in Kuwait. The tambura [lyre] came this way to Kuwait. Its source is Africa, like the Leiwa [a ceremonial dance], which uses the surnay [double reed oboe]. The Leiwa is considered among the arts that are hard in the sense of the complexity of its polyrhythms. Every instrument offers a rhythmic shape that’s different from the other. The Tanbura is used in Kuwaiti religious songs. You know the Tambura scale is pentatonic, not seven notes like the Arab scales. Ahmad Baqir, who used to teach us in this institute, wrote songs using the pentatonic scale And there is a special [6/8] clap with it. The tanbura is double sided, and has strings that are made of animal gut. Now unfortunately, it’s no longer hand made. There used to be people in Kuwait who made it, using cow skin, and it was played with a different kind of pick, not like the oud. All these are considered among the arts that arrived in Kuwait.

Tambura

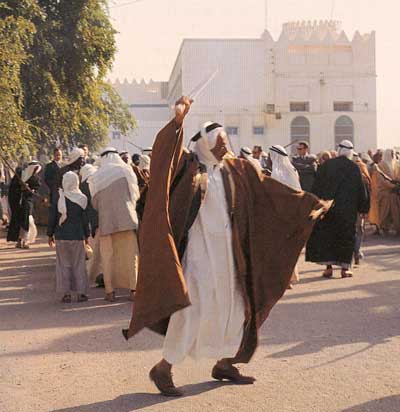

B.E: Dr. Bandar played for you a nationalistic song, an ardha, and apparently it too has an African connection.

J.B: Yes. It has a 6-beat rhythm, and that's a telltale sign of the influence of Africa. It's the same rhythm that you hear in many East African countries, and when you hear it in the Gulf, it's testimony to the influence of those African émigrés who came to the Gulf region generations ago. The ardha is a traditional, Bedouin war dance, sung by men before they go off into battle, with their swords, or more recently, their rifles, around and around in a circle.

When, in the 20th century, these young nation states of the Arabian Gulf wanted their own national anthems, they reached back into their Bedouin tradition and their African rhythmic styles, and they fused these things together with the ardha, and turned them into nationalistic songs. The song Dr. Bandar sing for me, “Wallahi ya Kuwaitna”, which means, "By God, O Kuwait of Ours,” is the Kuwaiti equivalent of “God bless America." And that says something profound about the culture of Kuwait, and the cultures of the Gulf, that also in their most formal, proud, patriotic music, there's that distinctive trace of the rhythm of Africa.

Ardha in Bahrain

Bandar Ubayd, on Jews in Kuwaiti music: Salih and Daoud al-Kuwaiti were, of course, Jews. They settled in Kuwait before the 30s. There was a Suq al-Yahud [Jewish quarter] then. This we used to hear from our fathers. They had a place. It was present in Kuwait. At that time, there was not this [hostility]. The religions are all from Allah. But Salih al-Kuwaiti, participated with Muhammad bin Faris from Bahrain, Mahmoud al-Kuwaiti. They migrated in the late ‘30s and worked in Iraq, in Baghdad, and they were famous. Most of his life, Salih lived in Kuwait, and was influenced in the Kuwaiti sawt. He loved this art. But in the 20s and 30s, there were not recording devices in Kuwait. He went to Baghdad and settled there, because they had studios. He participated with a lot of Kuwaiti artists. But Baghdad was a city of art, and the brothers found themselves there.

Bahrain

Joseph Braude and Ahmed al Jumayri

B.E: Joseph, tell me about the musicologist you met in Bahrain, Ahmad al-Jumayri.

J.B: Ahmad al-Jumayri is the most powerful musician in Bahrain. He has a seat at the table of the Ministry of Information and Culture, which means that he helps set the cultural agenda for the Bahraini educational system, for Bahraini festivals, and indeed cultural policy for the kingdom as a whole.

Bahrain Orchestra rehearsing (Braude 2006)

I met him in one of the main offices of the Bahraini Ministry of Information and Culture, which is also the place where the Bahraini National Orchestra rehearses, and while we were setting up the microphones, the adjoining room was filling up with players, some obviously of Arab Bedouin stock, and some of African origin, plainly resembling anybody you would find in East Africa. Ahmad al-Jumayri was every bit the straight shooter about Bahraini history that Dr. Bandar was in Kuwait. He plainly acknowledged the history of slavery in his country, which had such a profound impact on the history of culture in Bahrain.

Orchestra rehearsal in Bahrain

Ahmad Al-Jumayri, on Africans in the Gulf: You know, from about 200 years ago there was the slave trade throughout the world, and among them, there was the slave trade in the Arab countries, and most of them came this way, but many of them also were brought in as workers, because there was commerce among the Gulf states, boats going out from Kuwait and Bahrain, and heading out, outside the Gulf to the Indian [sub]continent, and turn behind the Arabian peninsula, sometimes in Oman or Yemen, and ending up on the African coasts, going out for provisions, wood and such things, and bringing with them workers, who work on the boat. They bring the workers with them back and forth, and when they come here, they settle here. But I believe that most of them [the Africans] are from the old slave trade, before 200 years or more, when the slave trade was predominant.

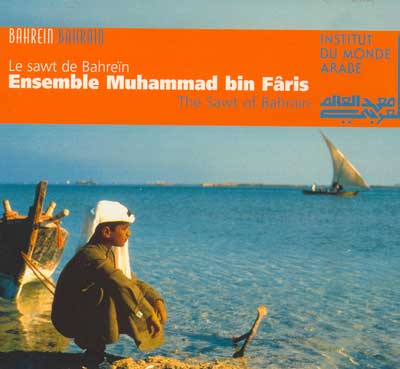

Sawt of Bahrain

They became Muslims and became a part of this Ummah, and got the nationality and the same roots and they married and worked, and now they are with us as brothers. Their grandchildren’s grandchildren are citizens, they have rights, and among them some became ministers and ambassadors and diplomats, and among them are singers. Who is very famous is Muhammad Ali Abdullah, he’s famous and he’s from African roots. And Sultan Hamad, one of the best singers of the Sawt arts in Bahrain, and he is African origin. Also Sabt Salih. Many of them, really. Also, and the women who sing the songs of special occasions, most of them are from the Africans. And those who sing the Fjiri songs, most of them also are from the Africans, because they are the ones who sang on the sea, and they’re the ones who preserved these songs and passed them on to the next generation, and they became a part of the Gulf people and became a part of them – their heritage, their culture, everything.

Leiwa ritual

We have in Bahrain the “Funun al-Wafida” [arts of those who come from elsewhere, an allusion to Africans]: The tambura, which is an instrument like a harp with a pentatonic scale, was definitely brought from Africa. We have the Leiwa, which is an African rhythm but its scale is Arabic music, and an instrument called the Surnay which is a woodwind instrument is used. The Lewa also is among the arts whose rhythm is African. It has more “tarab” and movement than the tambura, it’s something that has relation to religion, and the Zar [healing, trance ritual from East Africa, usually performed by women]. Do you know what is the Zar? It’s a dance for spiritual elation – like the jinn[spirits] – and this is with the tambura. It has a ritualistic, healing religious quality. But as for the Leiwa, it’s very danceable, singing songs of love, you play it at joyous events, the Leiwa. But it’s one piece, and the Lewa only men dance to it, not women. [This echoes Poul Rovsing Olsen’s recollection of an experience in Dubai where “a Leiwa transformed into a Zar when someone got possessed, but the music did not change.”]

Surnay used in leiwa ritual

B.E: Ahmad al-Jumayri spoke to you about a number of local khaliji genres, especially the “sawt,” which I understand means “voice.”

J.B: Traditional Arabic music has the key terms sawt and mawwal. The mawwal is a poem set to music without any rhythm. It typically crescendos into a passionate climax, and then resolves and is followed by sawt. The sawt is another poem set to music with rhythm. Sawt is dance music of the most traditional variety.

B.E: Ahmad al-Jumayri played especially beautifully when you prodded him to give an example of the taqsim, an introductory improvisation, in the old Gulf style. Describe that exchange.

J.B: Taqsim is a word Arabs use for a rhythmless improvisation on the oud, which climaxes and typically resolves, spilling into a song that you dance to. What is striking about the taqsim is how it's been streamlined with the advent of records and radio across the Arab world. A handful of really famous musicians in Egypt and Syria have perfected a style of taqsim playing that is now imitated all over the Arab world. It's got a flamenco component to it, and a sort of Mediterranean flavor that probably never would have been heard in the deserts of Arabia before. I wanted to know what a taqsim used to sound like, before the spread of records from faraway Mediterranean shores. And I asked Dr. Ahmad al-Jumayri if he could play one that he remembered from his childhood. And I was pleased that he said he could approximate what he used to hear growing up. It's a vanishing sound.

Joseph Braude and Egypt's Hakim

I am an oud player, and it was really exciting to hear this window into a world long gone, but it's barely been preserved, of an old-fashioned style of playing taqsim, nothing like the Egyptian flash that's imitated across the region today, that's got these lean meandering riffs, percussive, emphatic, maybe a little belabored. Desert riffs.

Sufis and Wahhabis: A Hidden World in Qatar

B.E: Let's talk about religious prohibitions permitted, and particularly about Wahhabism. Rovsing Olsen writes about Wahhabism in the 20th century suppressing musical expression. He writes about the oud having to go underground at a certain point.

J.B: Wahhabism, the state ideology of Saudi Arabia, is a puritanical, Islamist value system that tends to be quite repressive when it comes to secular music. It generally frowns upon music because music is associated with debauchery and corrupt pleasure. One of Wahhabism's ideological progenitors is Ahmed ibn Hanbal, whose Muslim legal rulings call for smashing musical instruments like the oud. The legacy of those teachings has not been friendly to the musicians of the Arabian Gulf, particularly in a country like Bahrain, which borders on Saudi Arabia, and which depends on oil-rich Saudi Arabia as an economic lifeline.

The nature of this impact also has to do with the economic symbiosis between Bahrain, a relatively oil-poor state compared to Saudi Arabia, an oil-rich state on its border. Bahrain has a liberal nightlife that has historically been a kind of mini-Europe, a weekend vacation spot for Saudis, a pressure valve for the repressive nature of the Saudi public sphere. It also is one big oil refinery for Saudi Arabia, which is how a lot of Bahrain's money is made. So the result of that is the exportation of Wahhabi culture into Bahrain, which has political effect, making the culture less liberal today than it was 20 or 30 years ago.

B.E: We know that Wahhabism has always opposed Sufism, the mystical orders of Islam. Isn’t that right?

J.B: Historically, the Arabian Gulf is an important capital of Sufism. Go back 500 years in Arabia and you find Sufism, the Islamic mystical tradition, thriving right alongside the rest of Muslim tradition. Today, the story is different. Saudi Wahhabism has undermined Sufism in a very, at times, brutal campaign, smashing Sufi shrines, and making certain Sufi practices illegal throughout Saudi Arabia. This is true to a lesser extent in the rest of the Gulf, where Sufism is only a faint memory for the local populations.

B.E.: Now, you had a fascinating encounter with a form of African Sufism in Doha, Qatar, and that encounter comprises the final segment of our program, “Africans in the Persian Gulf.” I want to hear more about that experience, but first, tell us a little about Qatar.

J.B: Qatar is a tiny state on the Arabian Gulf, but it has become a powerhouse throughout the world because it fuses oil and gas wealth with a robust, independent foreign policy. Qatar is the seat of Al Jazeera, the famous television network that has affected the way we talk about Arab public opinion. Everything we've said about Bahrain and Kuwait in terms of cultural makeup is also relevant to Qatar. But when I was there, I also experienced the 21st century face of African immigration.

The waves of people traffic from East Africa and the Horn of Africa into the Gulf never really stopped. Today, 80 years after the discovery of oil, you have Africans coming as guest workers in a country like Qatar. Some of them stay for decades. Abu Bakr Al Gadi is a person I met in Qatar who has lived there for 18 years. He is Sudanese, and he works in Qatar as a lawyer. What I discovered as I got to know Abu Bakr and his friends in Qatar is that there's a Sudanese community that maintains cultural ties with one other as well as the Sudanese interior, and they are right there in Qatar, and they have a measure of freedom to talk about politics, and talk about their culture, and even engage in those mystical Sufi evenings that were typical in their home country.

Abu Bakr Al Gadi, a Sudanese in Qatar (Braude)

Abu Bakr Al Gadi took me in for an evening of mystical chanting of a Sufi variety, but it wasn't Qatari. These were all fellow Sudanese nationals, who have their own pedigree of Sufism stretching back centuries in Sudan, and to have brought their Sufi traditions with them to the shores of the Arabian Gulf. Qatar allows its Sudanese and Egyptian Sufis to practice their mystical traditions within their living rooms. But there are some ground rules. They are not allowed to take it out into the public sphere, and they are not allowed to bring Qataris in with them. Everyone in this room was Sudanese, and it was an interesting melting pot of Sudan, that in today's atmosphere of civil war and ethnic strife, you won't find in Sudan. You have people from the South getting together with people from the north, and indeed, a handful of Darfuris would sometimes be singing along with them.

Sudanese Sufi gathering in Qatar (Braude)

Sudanese Sufi gathering in Qatar (Braude

B.E: That's amazing. These people are coming together in a foreign land under the context of this Sudanese Sufi practice.

J.B: This very gripping, soulful sound of African Sufism has its roots not only in the Muslim mystical tradition, but in the Zar, African mystical tradition of animists in Africa, that are doing similar things albeit with different texts. The Zar tradition involves possession and healing, and during this long evening, I watched a sort of an equivalent of possession happening right in front of me. A man started jerking bodily in an uncontrollable way in the middle of his chant, and I asked him after the break and we're having some food, "How did that happen? What's going on?" He said that the spirit of the Prophet Mohammed had overwhelmed him, and he was feeling him deep in his bones. His explanation might sound monotheistic enough, but that whole bodily possession experience is deeply intertwined with African animist mystical traditions, whether he uses those terms or not.

B.E: I'm very interested in the way of the politics of Darfur played out in the context of this Sudanese-Qatari community.

Sudanese Sufi gathering in Qatar (Braude)

J.B: Yes. On another evening, Abu Bakr Al Gadi gathered together some of the very same people for a political salon at his house. Abu Bakr’s many Sudanese friends in Qatar include no small number of Darfuris, and the presence of those people was particularly striking as I got to know them and got to see them becoming activists on behalf of the people of Darfur. There are thousands of Darfuris in Qatar, and tens of thousands of Darfuris in the whole Arabian Gulf. Many came there in the 70s when the Gulf rulers were building up their armed forces, and they were stocked by Darfuri soldiers, before they were eventually replaced by locals. Now, numerous Darfuris are well-heeled merchants in the Gulf, and they are a lifeline to their brethren in the Sudanese Interior, who are now suffering from the campaign of genocide or ethnic cleansing. My friend, Abu Bakr Al Gadi, here in Qatar, organized a group of Darfuris and got them together with Sudanese from all over the country, including the Khartoum capital, including the South. And they had political discussions and talked about a campaign of solidarity they can wage from Qatari soil in support of Darfur, and building solidarity in the Arab world for the people of Darfur.

Sudanese Sufi gathering in Qatar (Braude)

B.E: Remarkable. In an article you wrote about this, you mentioned that these Darfuri activists are sometimes dismissed as victims of Western propaganda. It seems a lot of Qataris are in denial about the Sudanese genocide.

J.B: What Abu Bakr Al Gadi was trying to do in Qatar for the people of Darfur has its parallels with the many activists in the US who are struggling to get the American administration to do something about the genocide in Sudan. In Qatar, there is the phenomenon of pan-Arab solidarity with the Sudanese government, and that is blocking this type of activism, but Abu Bakr Al Gadi, sitting there in Qatar, is a lone voice, struggling to raise awareness in the Arab world among Qataris about the plight of Darfuris. He's writing about it in Qatari newspapers. He's gathering Sudanese people together in his living room, and posting stuff to Sudanese websites, and really giving all of his energy and all of his spare time to this very just cause.

The Rising Profile of Khaliji Pop Music

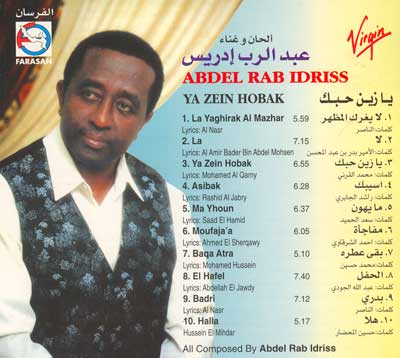

J.B: All this cultural mixing that you find in the traditional music of the Gulf you can also hear in the latest pop hits coming out of Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia. The same pentatonic, five-tone scales, the 6/8 African rhythms, can be heard and seen in music videos in Arabian music television. Khaliji, or Gulf music, is becoming popular even beyond the borders of the Gulf. You have Gulf tourists going all over the Arab world, and they bring that music with them. Now there are satellite television stations exclusively dedicated to music videos featuring the singers from these Gulf states. Some of the most popular khaliji singers in the Arab world today are people like Nabeel al-Sh’eyl (sometimes spelled Shuiel), Abdallah Al-Ruwaished and Husain Al Jassmi from Kuwait, Jawad Al Ali and Mohammed Abdu from Saudi Arabia, and the singer and composer Abdel Rab Idriss, who has written some of the most popular songs sung in the Gulf today, is of Yemeni and Saudi nationality, but of African extraction.

Remember that khaliji as a musical denomination is very modern. It comes in the last few decades. If you go back to the last century, to the 19th-century, you wouldn't hear that as the grouping at all. Because after all, the authentic, rural music of these different portions of the Gulf, and Iraq, differ from one another in remarkable ways, so to lump them all together as one thing is a more modern phenomenon, and it reflects marketing—coming up with names like "World Music" or "Latin" or “House.” Something gets a name when a record company determines that it has a market. So I suspect that the name khaliji as a type of music is inextricably linked with the rise of the Gulf as an audience for music. So for example, you have Rotana, which is kind of the MTV of the Middle East. And they now have five Rotana stations. One is classical Arabic music. One is 24 hours of Arab pop, Egyptian and Lebanese style, and they have something called Rotana Khaliji, which is 24-7 Gulf style, khaliji music. So there is this notion that, as in all parts of the globalizing culture, the disparate elements that have made up the complex tapestry of the Gulf get whittled down to a few recognizable things which are rhythmic, which are about scales, which are about the affectation of the singer, and it becomes known as khaliji.

Another consequence of it, again in terms of the post-oil-boom role reversal phenomenon we talked about before, is that you even have some Egyptian and Lebanese singers recognizing the large market that is khaliji music, singing a couple of khaliji songs on their albums as well, and venturing into this large market. And it gets very exciting. This is something that would have been unheard-of, I would say even 20 years ago, that a Lebanese singer would attempt to sing that kind of song.

B.E: What about lyrics? Is khaliji music distinguished by what the singers sing about?

J.B.: Well, first of all, Gulf music embodies an older, a slightly older tradition of entertainment in the Middle East, which features poetry in the music. Of course, Umm Kulthum embodies that tradition too. So many singers across the Arab world do. But, as we enter the popular verse and the marketing of music today, the two and three-minute singles that are recorded and broadcast, you find the Egyptian and Lebanese pop resembling American music in terms the content of what they're singing about. Very slang, not enormously meritorious in terms of the poetic value of the lyrics. By contrast, in khaliji music, it is still very common for the most popular singers to have extended love poems going on for maybe 8 verses, 12 versus. A song on that album of Mohamed Abdu that I was just playing is easily 15 or 20 minutes long, so there is a kind of the deference to the poetry, and it is not always poetry in classical Arabic, but often enough poetry in Gulf dialect, Saudi dialect. And that is obviously distinctively Gulf in style and its affectation, etc.

B.E: Tell us about Mohamed Abdu.

J.B.: Mohamed Abdu is probably the best known singer, and best-loved singer in Saudi Arabia, and it is widely known, and understood, that he is of African origin. He certainly has the features that would suggest that, and when Mohamed Abdu sings in a Gulf country, or occasionally in Lebanon and elsewhere, he has audiences enthralled. He is backed up by an orchestra, typically an orchestra of 32 musicians, and he sings songs that have a folkloric component to them. There is a high standard of poetry, not what you typically find in Egyptian or Lebanese pop today when you watch music television in the Arab world. He manages to fuse modern instrumentation, including everything from string instruments to synthesizers, with a certain authenticity that is understood to be authentically Gulf, authentically Saudi. He mostly sings in Saudi dialect, although sometimes also in Fus’ha, which is the modern standard Arabic, the modern adaptation of classical Arabic.

Mohammed Abdu is a distinguished and respected singer across the Arab world. Even for those Arabs in Egypt and Lebanon who are not particularly fond of Gulf music, if there is one Gulf singer who they will listen to, it would be probably either the Saudi, Mohamed Abdu, or the Kuwaiti Nabeel al-Sh’eyl, both of whom, incidentally, are known to have African roots.

B.E: What should we know about Nabeel al-Sh’eyl?

J.B.: What people know in the Arab world about Nabeel al-Sh’eyl is that he is Kuwait's leading vocalist. He is a whale of a man. He looks to me to be easily over 300 pounds, and he is one of the most cheerful people you'll ever see. He has the roundest smile in the Middle East, and he is a fixture of music video television. I think that the Gulf community of vocalists might have been a little slow to enter the world of Arab MTV, whereas Lebanese and scantily clad Egyptian pop stars like Ruby were among the first, but Nabeel al-Sh’eyl is a man really made for television, because he just embodies so much love and warmth, and when you see him walking through a fancy house and singing a song with adoring women around, you just feel like, "Wow, I don't know how many people like this were around 200 years ago, but we're pretty lucky that there's music television today, because it captures a very interesting form of entertainment." I mean how many 350-pound pop stars do we have in America today? I guess we have a handful. The other thing about him is that he has the stunning, tenor voice. He's like a Roy Orbison, if you ask me.

B.E: I see that there are a number of female khaliji singers too, like Huda Abdulla, the woman you met in Bahrain, while interviewing Ahmed Al-Jumayri. I love that she listed her influences as “Fairuz, Barbara Streisand, and Guns and Roses.” Is there a khaliji diva you think we should know about?

J.B.: I would say that the most popular female vocalist in United Arab Emirates is a woman named Ahlam, who according to popular newspaper tabloid discussion, at the very least, underwent significant plastic surgery in order to make herself look less African. A kind of a Michael Jackson phenomenon. The legend is she wanted to look less African so as to be more marketable across a broader slot of the Arab Middle East, but she is of African ethnic heritage, and extremely popular.

Final Thoughts from Joseph Braude

Traveling through the Gulf, and listening to the sounds of Gulf music as it's evolved over the past hundred years, it is amazing to see how much has changed, through the discovery of oil in the 30s, and the independence movements of the 70s, the formation of a self identifying Gulf style of music in the 90s and in the early 21st century, I think that going forward, what I'm going to be listening for is a more sophisticated, more nuanced Gulf identity, that is more proudly proclaiming its component parts, including its African roots. A Gulf identity that is reaching into Africa, as well as into its Arab neighbors in cultural kinship, so that the Gulf becomes more than just an Arab region, it becomes a world region…. so that the Gulf is more than just a component part of the Arab world. It's a region with its own unique trajectory that stands on its own terms, and has a special role to play not only in the future history of the Middle East, but also, in the future of Africa.

It is especially exciting and important, I think, to talk about the roots of Gulf music today at a time when you have this drawing of lines between national borders and ethnic conflicts throughout the Middle East and Africa. When people stop and look at the history of the music that's closest to their hearts, they realize how that music is inevitably a hybrid of culture, the African tradition in the Kuwaiti nationalist song, the Jewish artists who played in Kuwait City and wrote some of the songs that are sung by Muslims today. As an Iraqi, Jewish American, it is especially interesting to hear about the Jewish role in Kuwaiti music, which is small but quite distinctive. And I think that it's worth something to bear these roots in mind as we trace the musical history of the Gulf because acknowledging the blurred boundaries between ethnicities and nations is a part of healing ethnic rifts in these troubled parts of the world.