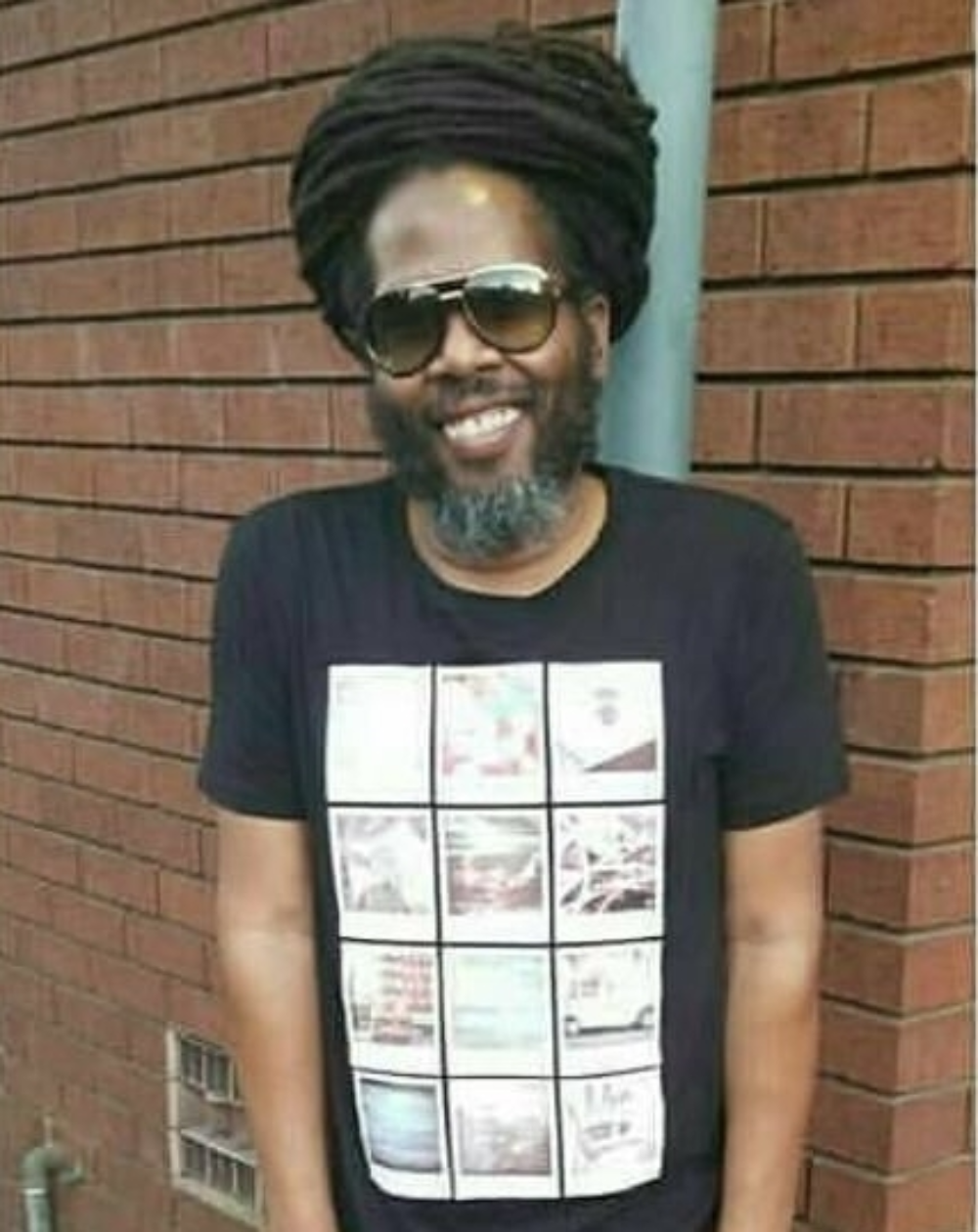

Reggae sound clashes, with their mix of entertainment, competition and trash talk, can seem like the professional wrestling of music—minus the fakery. And the Vince McMahon of the clash world is surely Garfield “Chin” Bourne of Irish and Chin.

Over its 20 years, Irish and Chin has promoted a slew of clash events in North America, the Caribbean, Europe and Asia, most famously the Superbowl of Sound World Clash. Besides traditional clashes, Chin stages an annual outdoor sound festival in New York and a clash on the Welcome to Jamrock reggae cruise. Chin also manages the fierce Mighty Crown sound system of Japan. He even hosts “Sound Talk,” a call-in radio show about nothing but sound clashes and culture.

It’s not hard to get Chin talking about the past, present and future of clash culture, which is exactly what he did in his Queens office a few weeks after this year’s U.S. Rumble, in which the juggling sound system Platinum Kids was victorious.

Last month, after this interview had taken place, the Platinum Kids went on to the World Clash in Toronto where they put up a good showing but ultimately lost out to the defending champion, Canada’s King Turbo. In a post-event press release, Chin hailed the emergence of multiple new players on the sound scene at this year’s World Clash.

Chin: I’m Garfield “Chin” Bourne I run a company called Irish and Chin Inc. which has been dedicated to the growth of sound system culture for 20 years now.

Noah Schaffer: So we just had the U.S. Rumble, which is part of the run-up to the World Clash. Can you explained why the format for the World Clash has changed?

The Rumble is basically a national championship. We’ve set them up in selected territories and all the winners get to compete for the World Clash title. Once upon a time the World Clash had all the best sound systems of the time: Bass Odyssey, Ricky Trooper, David Rodigan. But that was a time where sound sound system culture was more active, where a sound system could leave Jamaica and go to England and be a headliner for a nice dancehall show--a time where Mighty Crown was touring the world and come go to Germany and the U.S. and be headliners. As time went on we started to enter into a phase where the sound system brands became less and less of an attraction. The big names have slowed down. Some have even been diminished. So they play less. We entered a time where if you go to a stage show it’s not about the sound or the selector, it’s more about the artists. In the diaspora—England, Canada, Atlanta and New York—what started is that the promoters became the brand instead of the sound systems being the brand. So all these things allowed me to understand that we had to stop and start again. We have to use the knowledge we gained from the past and take another look at the structure and figure out a way to reintroduce the clash to today’s generation.

Why has there been a change in the clash market?

There is a generation gap in sound system culture. Many people don’t want to acknowledge it, but there is a generation gap. When I was 15, 16, I used to rush down to the Biltmore in New York because I wanted to see Bass Odyssey versus Addies or Bodyguard. We were trying to get into those venues because we aspired to be the next Ricky Trooper, the next Panther, the next Babyface.

Fast forward to this generation—there’s no 15 year old rushing to venues because they want to be the next Tony Matterhorn or the next Fire Links. That whole torch passing has just stopped, and I believe a lot of it is because today’s youth are more inspired by what’s going on in the diaspora as opposed to what’s going on where they come from.

When I was growing up my parents were Jamaican, I was born in the U.S., and I’d consider myself 75 percent West Indian and 25 percent American. Now it’s the opposite, kids think they’re 75 percent American or English or Canadian and only 25 percent West Indian and the day to day culture is reflected in what they do. And it shows in the dancehall. When I was a youth you wanted to be a sound man because that was part of the culture, but today’s youth, they don’t aspire to be selectors and sound boys and sound girls.

In addition you have to look at what we’re offering them. They are 75 percent influenced by American culture but our dancehall is 75 percent or even 90 percent West Indian culture, so you’re not get going to get the youth to come into the dancehall to listen to rub-a-dub or dub plates because it’s not part of their lifestyle. So to get them we have to figure out ways to get the people making the music younger and more relatable.

Because we’d done the World Clash and before that, Death Before Dishonor, in Jamaica for many years, we realized that the quickest way to get this change to happen was to change the World Clash format. So with this rumble series we come to different territories: Japan, Canada, the U.S., Europe, the Caribbean and Japan. The winners of all those rumbles become the national champion for that region. So now we’re producing more press and visibility by emphasizing not just the World Clash winner but also those regional winners. We’ve also created a league and arena with less emphasis on having to go to the dub plate shop to buy all these dubs, and more emphasis on talent, speech, presentation and knowledge of music. I’ve seen sounds spend $25,000 to $40,000 just to compete. But the next champion sound selector may be somebody just coming out of college who can barely buy books or pay tuition but they’re good at what they do which is playing music. So we don’t want to deny the youth the opportunity to come in because they don’t have the cash.

Were you surprised that this year’s U.S. Rumble was won by a juggling sound, which generally plays music for dances, instead of a pure clash sound that only does competitions?

No, because in 2012 I introduced the concept of getting juggling sounds to start to compete again. Once upon a time there was no such thing as this divide. Over the years sound system culture began to be split into two, this wall was created by industry officials. You had juggling sounds being told they were too soft to be in the arena, they didn’t have the hardcore dub plates. In 2012, with the decay of the vibe in the clash arena, I came up with something called RESET: Restoring Exciting Sound System Entertainment Together. Part of that was having juggling and clash sounds on one stage. In 2013 we had two juggling sounds: Metromedia with Skyjuice and Jazzy T with Renaissance. We got a lot of push back for it. But juggling sounds have a talent that clashing sounds don’t have and vice versa. When I stood at the door in 2013, people said to me as they were leaving, “Chin, Skyjuice entertained me,” and it was the same thing this year with Platinum Kids. They were able to use 45s, good forwards and the strength of their dubs. It’s no secret Platinum Kids don’t have the dub box other sounds have, but they were able to use their talent, and stretch out the 45s, so they were able to be stronger in later rounds instead of wasting the 45s in the earlier rounds. It probably would have cost another sound $35,000 to do what Platinum Kids did with $7,000 or $8,000.

Are we going to see more juggling sounds come into the clash circuit?

After Platinum Kids won the U.S. Rumble I was flooded with requests from juggling sound systems to [compete in future events] which is a great thing. These are sounds that play out all the time, so they have nothing to lose. So you see all the press that Platinum Kids have gotten and think, why not get that for myself?

But why wasn’t there a similar surge after Metromedia won the World Clash four years ago?

The only way this thing will backfire is if these juggling sounds come into the sound clash arena and win the title and then don’t keep clashing—then the whole operation becomes defeated. I think a lot of us were let down when Metromedia won based on the fact that we didn’t get the chance to see them kill a couple more sounds. That’s a major concern to me now: Will Platinum Kids continue to clash?

Let’s talk about the trash talking that each sound directs at its opponent. Is it really as personal as it sounds or is it more for entertainment?

The dialogue that is expressed in sound competitions is a mix—some of it is personal, some of it is entertainment, some of it goes too far. The sound clash culture has gone through phases—there was a time when no one would dream about disrespecting anyone’s mother on the microphone. That was a better time. They’d find other ways to get jabs and insults across, but then another generation came along and their weapon was verbal abuse as much as dub plates. And their fans cheered them on and it became this trend to try to insult your opponent. And if you have to talk about the mother or the wife or that’s O.K. and we bought into that—I myself was a fan of that—but everything has its time. There’s a Jamaican expression: “Too much of one thing is good for nothing.” At first is was about your sister, and that got forwards, now it is about aunties, the envelope is always being pushed. And it’s not about music, it’s about cursing. But the clash arena says don’t stop cursing. My friend the Jamaican broadcaster Colin Hinds says sound clash is pure expression, it’s not supposed to be in suit and tie. I understand him but see the need maybe not to be in a suit and tie but at least a pair of dress pants and a nice shirt.

On a related note, I thought the era of anti-gay lyrics in reggae had ended, but at the U.S. Rumble Platinum Kids played Buju Banton’s “Boom Bye Bye” [which advocates killing gays] and a huge amount of the insults slung by the sounds involved homophobic slurs.

It is clear that a lot of the artists realized the pressure [over anti-gay lyrics] was restricting their growth so they eased off it it. Now when you go to the sound clash culture, the dancehall space—and we’re not talking about dancehall as a genre, but rather the space where we entertain—that is supposed to be the purest form of dancehall so taking that away, well some people think that means dancehall is being bleached or isn’t pure anymore.

Dancehall has always been that space in which people were able to express their dislikes. Their dislikes with Babylon, the police, their dislikes with life, their dislikes with homosexuality, with anything, so it does become a challenge for myself as a promoter. Because it also means I’m always getting restricted from sponsors, because sponsors look at sound clash like a loose cannon. I can tell them this won’t happen, but can I really guarantee that it’s not going to happen? [Potential sponsors] would rather just not take that chance.

This is the challenge we have, and it’s a challenge to the growth of the industry. There are some things we need to get mature about, because they are hurting us in the long run, however the dancehall is run on a cultural outlook of West Indian culture, so when you go into the dancehall you are experiencing what West Indian people hold as their culture, whether you agree or disagree with it, it is what it is.

There are two different laws: everyday Jamaican society and the laws of the dancehall. In society people live their normal lives and do whatever they please. In the dancehall space if someone is doing something that is not in line with the law of the dancehall space they can’t admit that’s what they do when they’re not in the dancehall space. It’s that serious in the culture.

If you are someone that is not bothered by homosexuality, you can’t get into that dancehall space and say that, because the dancehall space will turn against you. That is how the culture is and it won’t change because the dancehall space is global. Anywhere where the dancehall happens is governed by the rules of the dancehall space. They have a law they have to abide by, even though the law might be outdated, or insulting to some, or harmful to some, the law is the law in the dancehall space, and I don’t know how to change the law of the dancehall space. I don’t know if it is changeable, the only thing that I can see happen is that the people who occupy the dancehall space age-out of the dancehall, and the people who come in after them come in with a different mindset and a different set of rules.

But as long as the rules are being upheld in the dancehall space you’re not gonna get rid of the cursing, the [verbal] homosexual burning, the things that sponsors and people are bothered by, it’s the law of the space. You have an artist saying “badman nah wear pink” and no one wants to wear pink in the dancehall. Then someone says the number of homosexuality is two, so everyone starts counting “one, three, four, five” because it’s the law of the dancehall space—I know some of these people who say "don’t do this and don’t do that" come out and do exactly what they’re saying “don’t do” when they’re in the dancehall space.

So in actuality the dancehall space is like watching a movie. The actors who talk these tough roles aren’t tough like that in real life, it’s not their lifestyle, but they’re following a script like an actor does to sell a movie.

You manage Mighty Crown, a Japanese sound, and one of the biggest dances I’ve ever been to was when they clashed with the white British DJ, David Rodigan, in Hartford. Why do you think outsiders are so adept at Jamaican sound culture?

There were so many people at that! I’ve been managing Mighty Crown for 16 years now, and I also book Rodigan. It’s not an easy road. People say it’s a bias towards Mighty Crown. They are probably boasting seven or eight world titles, they’re one of the most decorated sound systems in the arena, and I would argue that the Japanese [novelty] wore off a long time ago.

But there’s [this mentality] that when a Jamaican sound defeats Rodigan or Crown they are the best. When they get defeated it’s robbery because Mighty Crown or Rodigan are “white” and they’re black.

Music is colorless, but I see people of white or Japanese origin appreciate the music more than us from the West Indies. If I was around Mighty Crown and I thought they were trying to do harm to the business or it was a Vanilla Ice-type situation I would have departed from their company a long time ago. Same with Rodigan. These guys really have a passion for their culture and their mission is to let the world know about reggae and dancehall, so it’s not just about feeding their families and making money, it’s about this feeling that they were lucky enough to stumble across this great Jamaican music and they’re going to share it with the world.

People said to them, "dude, it’s not your culture," but Crown stuck with it for 25 years and now they’ve gone from having 500 people at their anniversary to filling a stadium with 40,000 people.

With Crown they are treated like kings in Japan for what they’ve accomplished. When they leave Japan and come back to the West Indies people tend to treat them like shit, and if they didn’t love the culture they would just stay home in Japan, where they have a clothing line, sneaker deals, a record label.”

Same with Rodigan. He was awarded a merit of honor by the Queen, he’s got a book out, and the fact that he will still go to a garrison in Jamaica and play a likkle tune and get a forward shows he loves the culture.

I recently saw a flyer for a clash that said "No Facebook Live allowed." Does social media help or hurt the clash scene?

I’m not a fan of social media. I see the positives of it, but I also see many, many negatives in social media. It can allow someone who has played no contribution to the growth of the culture to feel like they are the man of the moment. It can allow a soundman to believe he’s a champion when he’s not. Same with a promoter. When you put up a flyer and get all these likes it makes you lazy, you feel "my dance sell off already, everybody like my dance." You’re not intelligent enough to realize 95 percent of people liking your dance are not in your geographical region so they won’t be coming to your dance. A lot of the events we’re seeing that are flopping, it’s a social media hype.

So you get these dances where the promoter loses all his money because everyone watched it on Facebook Live. And you’re rewarding a sound with a trophy when there were only 100 people in the dance, so he’s happy because he has a trophy. And all the people who were entertained for free watching it online are happy. But it’s spiraling the downfall of dancehall culture. Someone takes out their phone and gives away what it cost the promoter $50,000 to stage. If the promoter tries to stop it then "promoter bad man who want heap of money for himself" but the person streaming it didn’t put out the money to entertain the community.

All the Facebook Live situation has done is take the place of the cassette man who used to come into a dance and and tape the dance for free and go to Halfway Tree or Jamaica Ave. and sell the tape, and when you try to stop them then you’re bad mind and the worst person ever. The lack of concern for people’s investment clouds the industry, and it will never change because people will never see that the lawlessness damages the industry. People care about partying now, and not about the culture tomorrow.

I want to be like Charles Barkley and [after my career] I’ll go sit down in the [TV] box and talk about the game as it is being played now, instead of wanting the industry to stop. I want to see another promoter take it to another level with better ideas than mine.

People don’t care that there will be no sound clash culture tomorrow. When white and green and blue and Chinese people start to take this form of competition that we have as Jamaican culture, and bring it to their country and make the necessary tweaks, we will sit here and say “they a tief, they rob Jamaica,” when we could have made the changes and refused to.

I’m sure when they take the culture to Europe and the white man is clashing there ain’t gonna be no homosexual burning, no your mother this, your mother that, that but white man will get 5,000 people. Take it to Japan, same thing. But we don’t want the 5,000 people. We want the 1,000 people because we want the right to say whatever we want to say in the clash, and that kind of artistry is now outdated.

And in closing I want to say this: any person or thing that does not evolve will dissolve. If we don’t evolve sound system culture, it will dissolve.

Related Audio Programs