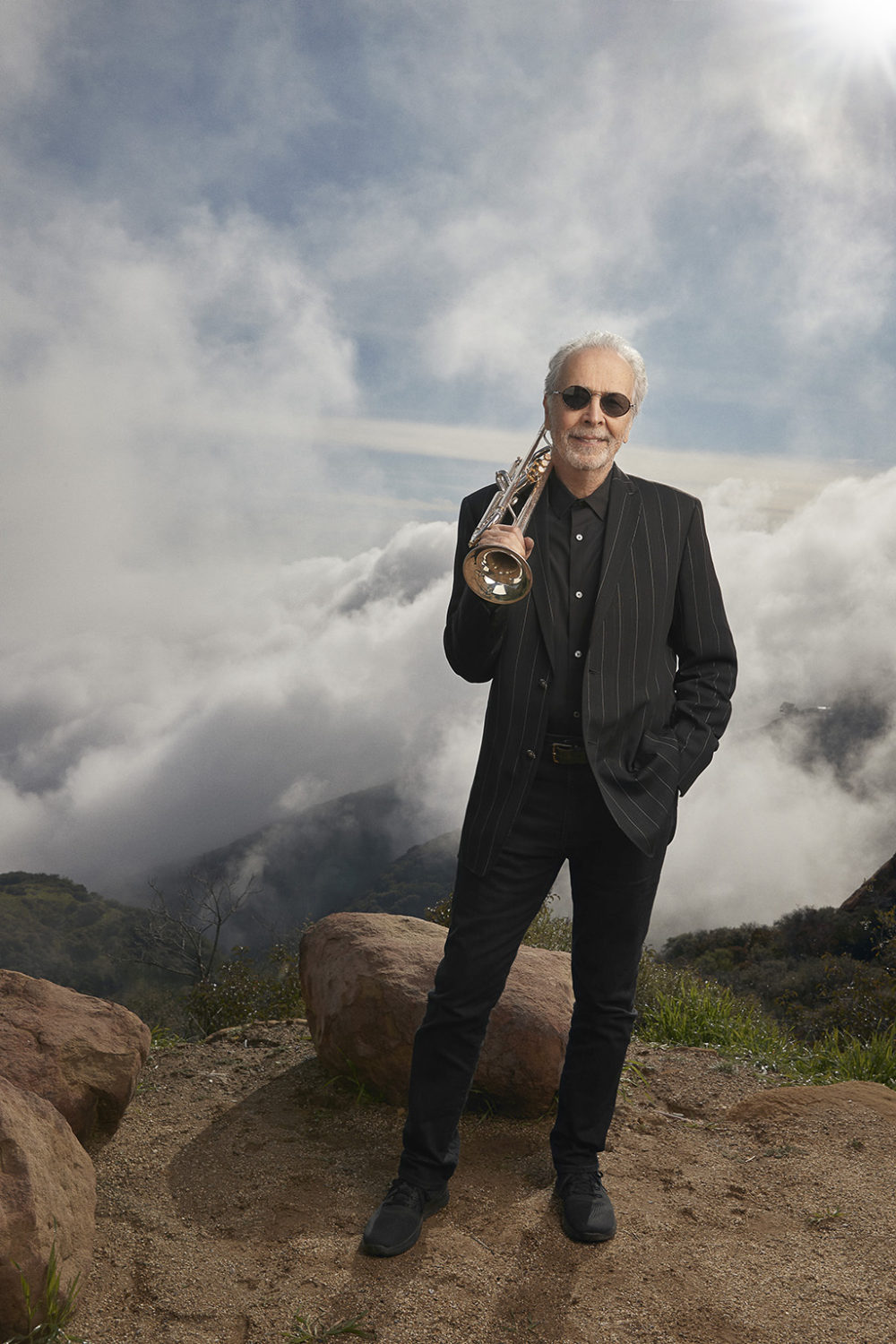

With nine Grammy awards and over 72 million albums sold in his nearly six-decade career, Herb Alpert has nothing to prove, but it turns out, a lot to give. Alpert is still likely best known for his work as trumpetist, composer and bandleader of the Tijuana Brass in the 1960s, and for creating A&M Records with his then-compadre Jerry Moss. But he is also a sculptor who creates beautiful large-scale abstracts, leader of a free-wheeling jazz quartet with his wife of 40 years, Lani Hall, and he is one of America’s greatest philanthropists for the arts. Among his generous endeavors, he famously rescued the Harlem School of the Arts in 2010. The school is now thriving and on solid ground—money well spent.

For the past 25 years, Alpert has also funded the Herb Alpert Award in the Arts, “an unrestricted prize of $75,000 given annually to five risk-taking, mid-career artists working in the fields of dance, film/video, music, theater and the visual arts.” For more on the history of these awards, check out this short video. The 2019 winners will be unveiled at a gala event on May 13 in New York City, and Afropop will be there.

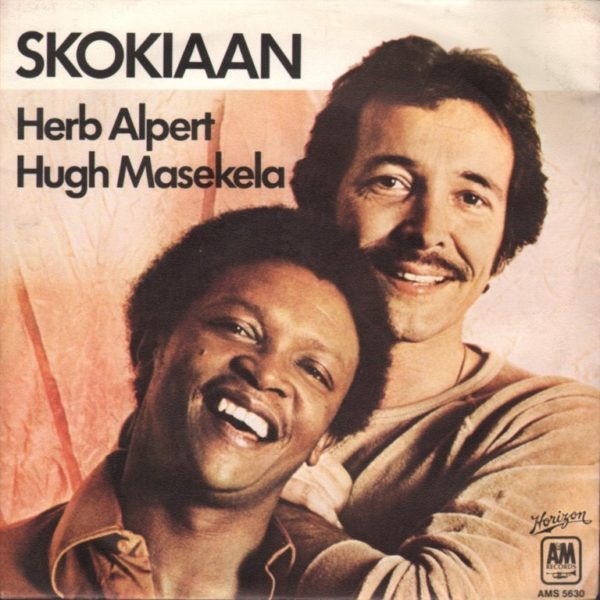

Afropop’s Banning Eyre spoke with Alpert from his home in Los Angeles about the awards and more. This is the third time the two have spoken for afropop.org—most recently about Alpert’s work and friendship with the late Hugh Masekela. The conversation always begins the same way. The phone rings and…

Alpert: Herb Alpert here. How you doing?

Eyre: All right. Right on time. Thank you very much.

You’re welcome.

So you've been giving these arts awards for 25 years now. Tell me how it started.

Well, it was just the idea that our politicians don’t seem to get it about the value of the arts. The arts are a core part of my foundation’s interest. And I love it. I love jazz. These are living art forms. They’re ways of showing what’s happening in the world. Can you imagine a movie without music? I always gravitated towards those artists that were willing to do whatever came out of them naturally without concerning themselves with whether you liked it or not. They were just following that road less traveled. I always loved those artists, and those are the artists that we’ve tried to find through the Alpert awards.

I love that you are looking for risk takers, people who are pushing boundaries. But you also specify mid-career artists, people who made it over those first hurdles, right?

Yeah, the first hurdles except for the money. No, these artists are struggling. They’re trying to do something that is uniquely special, uniquely their own. I think it deserves to be encouraged.

Going back to the beginning, you’ve been involved in philanthropy a long time. This is just one piece of the things you do, but I want to get a sense of what that moment was like when you clicked and thought this is something you needed to do. Five artists, five disciplines, once a year, and this amount. Was there a moment when the whole vision crystallised?

No. It kind of morphed. We tossed around ideas and then came to this idea that just seem to make sense. There wasn’t a master plan. We didn’t have anything on paper. You know, I’m a knee-jerk artist. I just had a feeling that it would be nice to support artists who are trying to do good things and just need a little shove. These artists that are in mid-career. Give them a little boost to know that somebody is appreciating what they’re up to, and let them take it to the next level. You know I honestly think the heart and soul of our country is shaped by our artists, and our politicians don’t get it. They just do not get it, for some reason.

We feel that here. Our program has relied a lot on government support, and at times it’s been generous, and at times not, particularly of late.

It’s a sad situation. Art is all about freedom, especially jazz. I love jazz because it is about freedom. That’s what we’re all looking for, and around the world, it’s the same song. People want to be themselves. They want to be free.

This whole idea of risk taking and pushing limits by finding people who are going places that maybe the market is not driving them. Their hearts are driving them. Obviously that is fantastic for those artists to get this kind of support. It’s a beautiful thing. But I wonder if you are also thinking about having an effect over the years on the very nature of art in America by pushing at the edges like that.

Well, I can’t quantify what the effect is. It’s just something I have to do personally. I have been extremely fortunate. I guess you’ve seen my story. I started playing when I was 8 years old where I got this opportunity in my grammar school. It changed my life. I’m an introvert. I’m a card-carrying introvert. My trumpet was speaking for me. I see how it transformed my life, and I feel like it’s something that kids need to experience at an early age. Whether they’re playing an instrument or acting or writing poetry, sculpting, painting. It doesn’t really matter. They can express their own creativity through that, and if they stick with it, they get to appreciate their own uniqueness, and if they can do that, maybe they can appreciate the uniqueness of others.

It's surprising that you say you are an introvert. Having seen you perform with your quartet at the Café Carlyle the last few years, I must say, you don’t come across as an introvert on stage.

Well, that’s the interesting part of it. I can play for 10,000 people and feel completely fine and free, but put me in a room full of people that I don’t know, and I’m a basket case. [Laughs]

Unless you’re holding a microphone. You may not know anyone in the audience, but you are very easy with them in that setting.

Well, it’s different. I can be myself.

I guess you know they’re there for you. But they seem to love it when you ask for audience questions and interact so directly with people .

It’s fun. It keeps it fresh. There’s a lot of spontaneity in the show that we do, so every night is different. You know, in the '60s when I had the Tijuana Brass, on tour we pretty much played the same thing every night and it was O.K. for then. But that’s not what I like to do now. I’m basically a jazz musician. I like that spontaneity, that of-the-moment kind of feeling. It keeps me going.

As I mentioned the first time we spoke, I pretty much grew up with the Tijuana Brass. When I was very young, my mother had the early records. I was 9 or 10 years old and I really wanted to play trumpet. I ended up playing guitar and that’s another story. But I think what I loved about your records was the way they evoked Mexico. That kind of affected me because it showed the way music could be a way of traveling, and in a sense, that led directly to my work with Afropop.

[Laughs] So I was the travelogue of your life?

In a way. You were someone who communicated the idea that through music you could go places. Going Places. There it was.

Yeah. Well it’s true that through the arts you can go places.

More recently, I have learned about your sculpting. I want you to talk about multidisciplinary arts. You’re a musician and a sculptor, and in these awards you are spanning all these different disciplines, these five categories of arts. This is something I’ve been thinking about lately, the need for the arts to talk to each other, especially in educational contexts. Kids can get that pigeonholed thing: “O.K., I’m a poet.” And that’s it. But the idea of bringing different arts together and having them talk to each other seems necessary and powerful. And I think your awards recognize that.

Yes. It’s the community of artists. It’s strange, now that I’m semi-famous with people who know my music, I run into an artist that I happen to like and I find that they know me. Years ago, I was in Portofino, Italy, and I was walking on the wharf there, and walking towards me was Rex Harrison. I didn’t know Rex Harrison, but I stopped and said, “Man, I really appreciate what you’ve been doing with your life.” Blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. And I introduced myself. “Hi, I’m Herb Alpert.”

And he said, “You’re Herb Alpert? Man, you got to come up to my house because I have a whole section in my music collection.” Anyway, he invited me up to his house. I saw his collection of CDs that he had, and I was in there as one of the artists. I don’t know. There’s a whole family of artists who really relate to each other. There’s one common thread that I find runs through all great artists. They are all honest, honest with their art. Whether Republicans, Democrats. It doesn’t matter. Artists have this honesty about them that touches me.

I can’t remember if it was in the video or something I read, but you said that this award gives an artist room to make a mistake. I found that interesting.

That’s beautiful. I think of the great musicians that I love. Miles Davis certainly comes to mind. He didn’t think about making perfect music. There are two types of artist as I see it. There are the artists that are playing the right stuff, painting the right thing, dancing the perfect thing, you know. And then there are those artists that are looking for the right thing. Those are the Miles Davises, the Coletranes, the Charlie Parkers of the world, the Picassos. Those are the people who don’t really care what you think about it. They’re just doing their thing. Amen. That’s what I’m hoping to promote with these awards. These are artists that are on their own path, so let’s give them a chance to show us what they’re doing.

Are you familiar with the singer from Mali, Salif Keita?

I’ve seen that name. But I don’t know him.

He is kind of a legend in our world, and he’s just made what he says is his last studio album. He started back in the '60s really. But looking back over the whole career, boy, is that ever an artist who followed his own muse. Every record is different. He got a Grammy nomination for his album with Joe Zawinul, but he’s also made a rock album with Vernon Reed, a French pop album. Through all that, the basis of his music has always been deep Malian traditional stuff. But he is definitely the kind of artist you are talking about, a person who doesn’t follow the market, but just does what he wants. And it doesn’t always work. I would say some of those things were mistakes. But I love the guy. He’s one of my favorite musicians of all time.

Well, that’s it. You know Wayne Shorter was part of the Monk Institute – now it’s the Herbie Hancock Institute here at UCLA… but Wayne, people would ask him, “What is jazz? What does it mean to play jazz.” He’d say, “There’s no such thing as jazz. There are people who create spontaneously. That’s jazz. Whether you're a pop artist or whatever kind of artist you are, it doesn’t really matter.” He doesn’t flip into that category that the jazz has to be a certain thing, certain sound.

I remember him playing that great stuff with Joni Mitchell, and I think he’s actually on that Salif Keita album with Joe Zawinul. Wayne has certainly never limited himself.

Exactly.

What is the role of CalArts in this award process? I see them prominently mentioned in the P.R.

Well, they administrate. They do the nuts and bolts.

And I read that the artists who win get to do a residency there.

Well, it’s not mandatory. They usually do a two-week residency, but they don’t have to. It’s an unrestricted award.

Nice. You know, I think about the world we deal with, where so many really talented artists are scrambling to make careers in difficult situations in Africa and the Caribbean and such. I wish there were people in their worlds who would think the way you do. Because if you think our government is tone deaf to the role of the arts, some of these African governments are even worse. And it’s terrible, because they really have the gold there. They could be using their musicians as an asset. In some cases they do. South Africa’s better. Senegal has Youssou N’Dour. But in general, the leaders just think about money and industry, and they don’t really have the kind of vision or tradition of philanthropy of the sort you have exemplified. I wonder if you’re aware of anyone anywhere in the world who is showing this kind of visionary generosity towards the arts, whether or not they were inspired by you.

I haven’t really thought about that, but I did think about: "If I can do it, you can do it. Tag, you’re it." By example, I hope it does rub off on some people.

Thanks so much for taking the time to speak with us. We will look for you in May. Hopefully we will have some decent spring weather by then.

East Coast weather always scares me. I remember one time watching buses sliding around on the streets in New York.

Luckily, we haven’t had much of that this year, but you never know.

Well, good luck, and thanks for all the stuff you’re doing, not just writing about me, but all that stuff you just told me about. That’s beautiful. Keep it going, man. We need more of you.

Thanks much, Herb.

Related Articles