Just to get it right out of the way: there aren’t any brothers in Meridian Brothers: the band is Eblis Alvarez’s sandbox to play in, and expands beyond the Colombian artist only to play live—until now that is.

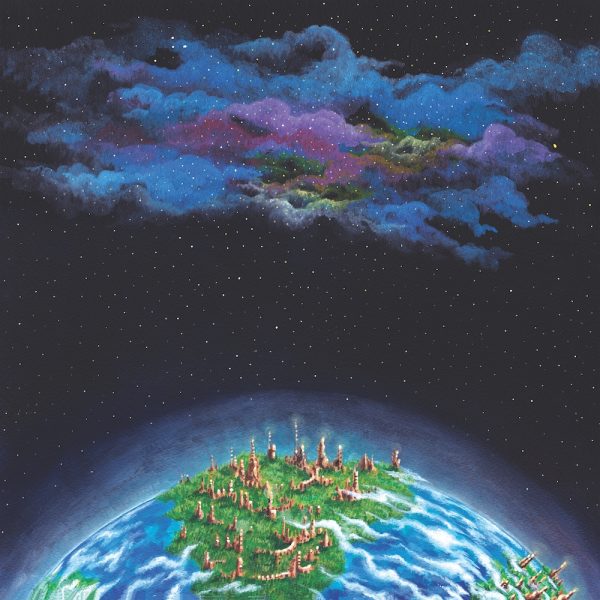

Alvarez’s first collaboration under the Meridian Brothers name brought in fellow Colombian Ivan Meddelín to play accordion. Based around Meddelín’s instrument, Alvarez translated his warped sensibilities from last year’s genre exercise in cumbia, Cumbia Siglo XXI, to an exercise in vallenato, music from Colombia’s Caribbean coast. Titled Paz En La Tierra, the new Meridian Brothers album has songs about would-be religious sects devoted to vallenato singer Diomedes Diaz, interplanetary colonialism, and how amorous infatuation with a brunette measures up to a world of government spies, fake news and global pandemic. So, there’s a lot of continuity there.

Afropop’s Ben Richmond Skyped with Alvarez from his home in Bogota. They talked about the new album: How Alvarez’s postmodern music is received in Latin America, and the idea of making something new in a world of instant communication, endless memory and constant noise.

Edited for length and clarity, allow him to introduce himself.

Eblis Alvarez: My name is Eblis Alvarez. I'm a musician playing in mostly two projects—Los Pirañas and Meridian Brothers. I'm also a composer, like sheet music and other styles like film and other kinds of dispositions of music. That's what I do. I live in Bogotá; I live and work here.

Ben Richmond: For listeners who aren't familiar can you describe the Meridian Brothers as a band, such as it is a band?

The Meridian Brothers is a personal project first. It's kind of a playground for different ideas as I use it as a composer for different media and forms of art, even the language and literature that comes from art. It's basically a center of production of different art forms, of course centered in music. And with the project, the first thing is the records--I'm very interested in recording and developing sound on recordings. The band or the project started as a band 12 or 13 years ago, and there's a branch of live music there.

How long have you been a musician?

I think all of my life, all of my memories. I entered the conservatory at eight years old. I studied classical music, then I started with guitar. I've just been in music all my life, in all its approaches.

You've got these different projects and places to put things you compose—how do you decide what song or ideas go with which project? Do you have that in mind before you start?

I think each project has a kind of profile. For example when I talk about Meridian Brothers, I would use the word "literature." It's kind of a story to tell in each record, in each sound. Each record has a particular way of developing a language of itself. Like classical composers who compose for instruments that they don't really play, or a writer who creates characters in a fiction story, I describe the Meridian Brothers like this, and this is how I decide how to put a song with the Meridian Brothers. Los Pirañas is playing improvisation with the three of us, working with whatever they do as a personal entity. And so, when I get a commission for writing for instruments like ensembles and so on, I do that and I choose the proper material for this project.

There's something really postmodern about describing music through literature, or thinking about through characters and such. It's a cool approach.

It's a cool approach but it's also, like, mandatory. This is how art has become in the 20th century mostly. Before, art was mostly a sensation. It was sensation and it was very communal and local due to the slow speed of communication. But since the 20th century art has become like speech around it and a lot of classification and taxonomy. Art has developed a lot of stuff around the sensation, which for art is mostly an emotional sensation. So for me it's mandatory to develop that around art.

I think that brings us to the new album, Paz En La Tierra, which to my ear felt like a real change from the previous albums. Can you talk about what changed in your approach for this one?

Actually, the last album and this one had the same approaches, though it sounds very different. Because the approaches that I've been working with the Meridian Brothers, over the last four years, has been exactly as I was saying. A lot of literature and concept around the sound. So the last album, Cumbia Siglo XXI, was around a particular style of Colombian music, a particular format. And I developed a concept around this music. It has a kind of historical and anthropological center. The same happened with Paz En La Tierra. I just changed the center, changed the format, to another spotlight, which is what I call "accordion format." Popularly it's called vallenato but for me it's accordion format. Because there's a lot of styles and stories around the accordion and the way the accordion is put into those musics. Also, different places among the Caribbean. So it's the same approach but it's a concept that develops with literature, with speech, with the concept. Departing from those abstract concepts, it then goes to sound.

The accordion is the first thing that strikes you, one second into the album; Ivan Medellín playing the accordion. But you wouldn't limit it by calling it a vallenato sound? It's bigger than just the Colombian coast?

It's Colombian coast, because the accordion format comes from all these states that touch the Caribbean, except for one or two states. And you can see also it's mirrored in the Dominican Republic, in Puerto Rico, in their accordion playing. But it's centered on the Caribbean with all its classifications. You got deeper and deeper and you find more and more classifications and partitions of the style.

How did you connect with Ivan Medellín?

Ivan has been around. He's one of the new generation of important musicians in Bogota and Colombia. As usual I'm following what new generations are doing--their projects and their approaches, because, you know, we're getting old! I'm an older generation than him. I knew him first as a keyboardist, but then when I saw him playing the accordion, I thought “wow, he's so talented!" He plays accordion, he's also an engineer, he plays percussion. He's a total genius. So, for long years, I've been dreaming about this project. I had to that. It was in mind for several years to do this accordion album. When I saw him, I thought "this is the moment." By chance we were also working on a documentary. I was hired to do a documentary and I hired him to work with me, and this was the opportunity. And it was very fast. We did the record just three months ago. It's very very very new.

It sounds like on other Meridian Brothers releases, the songs are very modular. There's a base of rhythm and bass and things are added and taken away. The accordion sounds like single takes, from left to right. How did using the accordion change your approach?

It does sound more compact in a way, because it's a standard style. I didn't change anything, so maybe this is the reason, when it's something common in the subconscious of the collectivity, it sounds tight. But on previous albums with the Meridian Brothers, I have to make up the style. This is why it sounds unnatural, because when I'm developing other formats, far from the collective unconscious, it sounds unnatural. This is why, because it's not part of the mind collective, or collective mind.

It seems like the vocals are more forward—and maybe sung in a lower register—than on other albums. Is this album more lyric-forward than others? Or is that part of the vallenato sound?

This is another characteristic of the Meridian Brothers. Since some records ago, I've begun to experiment with different characters in my voice. Sometimes I choose one register, sometimes I choose another. Fortunately I happen to have a wide range—I can sing very high and very low. So I could choose. The other option I have is to transform the vocals with the computer, so I have a whole palette of vocals to choose from myself. This particular time, it was a path I was following for some time, the Enrique Diaz path. I always choose some voices that I could imitate. And since I wanted to do it very in the canon, into the standard and classical format, so I had to find someone I could imitate. I couldn't do it quite right, but Enrique Diaz was the right way to find the accent and the modulations. Of course you hear my voice clearer because in vallenato and in accordion music, the voice is always on top, it's the most important thing. So I put it in that way. Sometimes, some other styles of music have the voice in the back.

I could make a comment here. We are not developing new culture anymore. Communication has gone too far, so now it's impossible to find something new. So now, we as musicians are working as persons in society who are curating what is around in culture, available to consume and recreate. It's not like in the '50s or the '20s of the last century, when societies were more enclosed, so people could use their subconscious and imagination to create new things. The humans of this era are not able to create new things. And it’s not because we're less intelligent or whatever. It's because we're full of the noise of information. So as an artist I have to have a different approach, which is to curate what I have in culture. I have records, I have files and websites. So this is the reason I'm not creating something—I'm taking Enrique Diaz's voice with the accordion format, and I choose a context. It's like a video game actually. I'm choosing the role I'm putting in the record. That's the comment.

This is why the voice is in front. It's not a development or an improvement. Sometimes I choose to put it back because I chose those particular styles.

Something I've always liked about Meridian Brothers is that there's always been something like clear references, and a feeling of how it was put together there but, even though you say there's nothing new, there's no mistaking it for something old. It's not cumbia from the '60s or '70s. On this record, maybe it's what the songs are about that tips the listener off that there's something else going on.

Yeah...if it's something else going on, it's the format and approach, but if there's something else I'm not aware of it. [Laughs]. I made the record like I always do, same microphone, same studio, same situation. Of course the accordion is different, and it’s my first collaboration with another musician. That's new.

Do you do a lot of touring in South America?

Yeah, we've done South America. It's much more difficult—just as far as infrastructure—compared to Europe though. Traveling from one country to another in Europe is like traveling from one state to another state in Colombia. Everything is very different. Both the infrastructure and the audience are very different. Because in Latin America, there is much less of a consumer layer of people. And things are much more segregated in taste and in possibilities of consuming art. Because of those facts, it's more limited, but we've done lots of concerts in Latin America too.

When you're playing in Latin America, do people recognize the forms you're playing for? They must occasionally really know how to dance to what you play.

There is a natural understanding of the music. But what happens too in Latin America is that people are much more picky. It's not just, "oh it has a beat, let's dance to it." If you go to Brazil, they want to listen to their Tropicalia numbers. If you go to Caribbean...I don't even think that Paz would go over that well. It's a whole tradition of what people want to listen to. You have to have a name. It's not "Oh I'm an artist and I'm working with this." People won't take it. It's very difficult to get in your own place. I think it's pretty normal. People are much more picky with their own people. I don't know why it's like that. But it's like that.

Do you have any touring coming up this year or is everything still on hold?

I took the COVID thing as a sabbatical year. I just devoted myself to those two records. But now we are rehearsing again and we're going to tour again next year.

Are you coming to North America?

We'll see! We have some suppositions but we'll see how it works out.

Related Articles