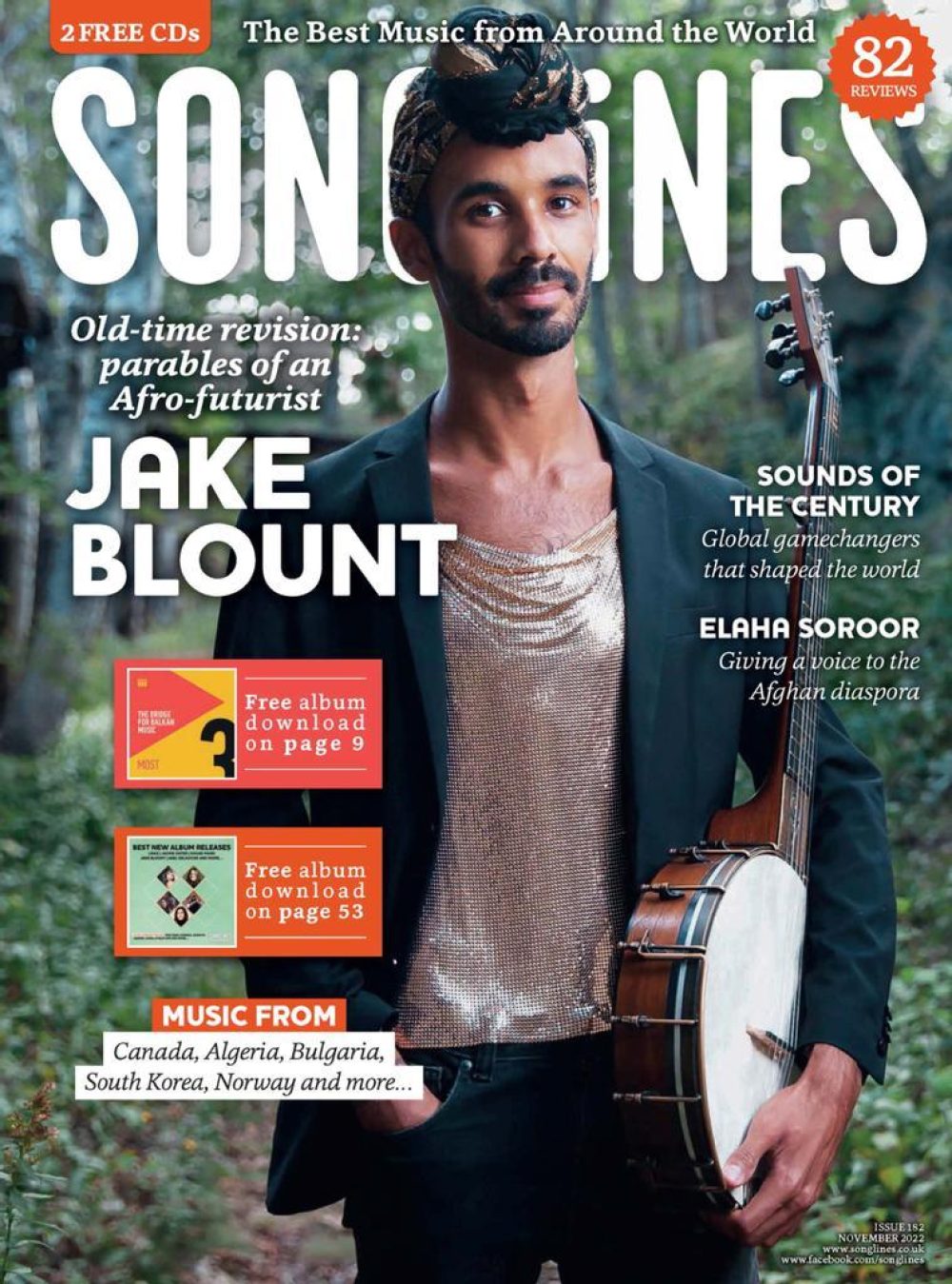

About a year ago, in December 2021, I spoke with Jake Blount about his unique exploration of African-American folk music. Blount’s 2020 album Spider Tales features inspired reworkings of mostly 19th century songs by overlooked African-American composers. This year, Blount reshuffled the deck with a still more ambitious album, The New Faith(Smithsonian Folkways), which has gained him significant attention and landed him on the cover of Songlines magazine. The New Faith is an Afrofuturistic concept album imagining the religious rituals of a band of African-American survivors following the coming environmental apocalypse. Amid a new collection of reimagined Americana songs, we get a narrative beginning with:

“After humanity’s debt to the planet came due, our ancestors crawled from the wreckage of their sunken cities and out of the deserts where once they had grown food enough for millions. Chance brought 30 survivors together, hundreds of miles to the south of here. Worn down by storms and starvation, they set their sights northward, and followed the coast to find a new home...”

From there, we get a musical journey featuring Blount’s fine fiddle, banjo and guitar playing, and crisp, soulful vocals, along with percussion, a humming and singing chorus of voices, and the rapper Demeanor occasionally adding to the story. The album is bold, risky, provocative and ultimately a landmark in American folk music. Clearly it was time for us to speak again, which we did over Zoom, from his bedroom studio in Providence, Rhode Island, where The New Faith was recorded during the pandemic.

Banning Eyre: The way I see this album is both as a literary and a musical work. I want to start with the literary side. You were inspired by Afrofuturistic fiction writers Octavia Butler and N.K. Jemison. This genre is kind of new to me. I only learned about it when I interviewed Toshi Reagon last year. But has this stuff been part of your DNA all along?

Jake Blount: I think reading speculative fiction is absolutely part of my DNA. That's been my favorite genre of literature since I learned to read. So that's a definite yes. Sometimes sci-fi. Sometimes fantasy. Usually one involves the other. That's always been an intrinsic part of both my taste in other media and what I'm trying to do with my own stuff. I think I specifically got into Afrofuturism after graduating from college. It was about 2019 when I read N.K. Jemison’s earth trilogy Broken Earth, and my entire world changed. I had never read anything like that before, and that was my gateway into digging deep into the rest. I had read one or two things here and there before, but she definitely was the one who showed me what I wanted to find in it.

So all that was in your head when you had the idea to put this album together. I'm curious about the moment of conception. How did you decide to make this both a musical journey and also tell a story with spoken words?

One of the important parts of my framework whenever I put a project together is to think holistically about the thing I'm trying to represent. In Spider Tales, that was me trying to represent this broader folk tradition, and that meant that I pulled from a lot of different sides of it. So I made the choice that we're going to do some country things, we're gonna do some blues things, we're gonna do some string band things. On this one, I really decided I wanted to do a deep dive into a specific type of old recording. So I decided that the thing to do would be to emulate Black religious services as they have been set down on recordings. And usually, if you listen to those full sets of recordings, rather than just the snippets that appear on compilation records, you will hear singing, and then you'll hear these passages where people are humming or singing, and somebody is praying over the congregation. I wanted to use that format because that's something that I have seen happen in church. I've been in the room where that happens. And I find it a really moving and unique signature practice that comes in that tradition. So I decided that I wanted to do that.

This just presented itself as the most obvious place to start, because in that context, people are reciting parables. They are preaching about the way that they view the world, and the way that their theology intersects with reality. Those moments, even though I love the music, are some of the more impactful for me. That's where I'm getting a really concrete and clear perception of how this person sees the world, and the significance that they feel their worldview has. That felt like the right way for me to put the background information in without obviously info-dumping on the listener.

I’m curious about something you write about in the sleeve notes, your ambivalence about Christianity. You talk about how the songs “broke me of my of atheism.” I'd like to unpack that a little. I relate to to your experience quite well because I also was raised in a quasi-religious family, and then at a pretty early age decided that I was not buying the dogma, for some of the same reasons as you. But I also love gospel music and I love a lot of Islamic religious music. So even though I have complicated feelings about the dogma and practice and history behind these global religions, the music has amazing power. And of course, it’s not just music. So much great art is inspired by what you and I might call far-fetched religious beliefs.

It’s true. It’s true

So talk about that, and the way the music “broke you of atheism.”

I guess I have articulated that I feel this kind of strange push and pull, because on one hand, there's a lot about the institution of the church that I don't support. There's a lot about the beliefs of the church that I don’t support. On the other hand, I also have to be respectful as a Black person in America of the fact that I have civil rights because of the church. That would not have happened without that organizing structure, and even though we know that in the moment where it was organizing it was boxing out women and queer people who were doing a lot of the work. So, you know, take the good with the bad and I think that's part of the thing.

We have secular music that comes from back in the day. A lot of it is the kind of thing I was working with on Spider Tales. But when it comes to a historical text that comes down from my ancestors, because they were not taught to read and write, because they were legally not allowed to be taught to read and write, these songs are what I have. This is the text that I have to tell me how they saw the world and what their religion meant to them and who they felt we were supposed to be. You don't get that many places and I do think that working with this repertoire, I became aware of multiple cases of songs that have been kind of subsumed under a Christian spiritual tradition that I don't think are Christian. Right? Like I think that the song “Death Have Mercy” on this record is not a Christian song. The only God that appears in that song is a personification of death. So that opened my mind to what these songs could be. But I think the broader spiritual experience of playing the music is something that I have a hard time articulating, like the feeling when I’m in a really good jam space, or when I hit that point of not necessarily finishing a song, but hitting the point working on an arrangement where it all suddenly gels, and the pieces that I've been trying to put together suddenly fit. I feel like there was more than me in that moment. I could not have made that happen. I did not do that.

When it comes to this album especially, this was a case of me trying to put together a lot of things that I was under the impression had never really gone together in that way. Obviously I knew that early banjos and drums and fiddles had all existed in the same space at the same time. But the way the scholarship has depicted the banjo up until pretty recently is that it was this secular thing that religious authorities were not into. I learned something after finishing this album where I was like: “Why does it have to be that way? Let me put the banjo and the drums and the fiddle in this culty religious context, and really work dance into the visuals of the album.” Because that's also a critical part. You don't have Black music without dance. It doesn't happen.

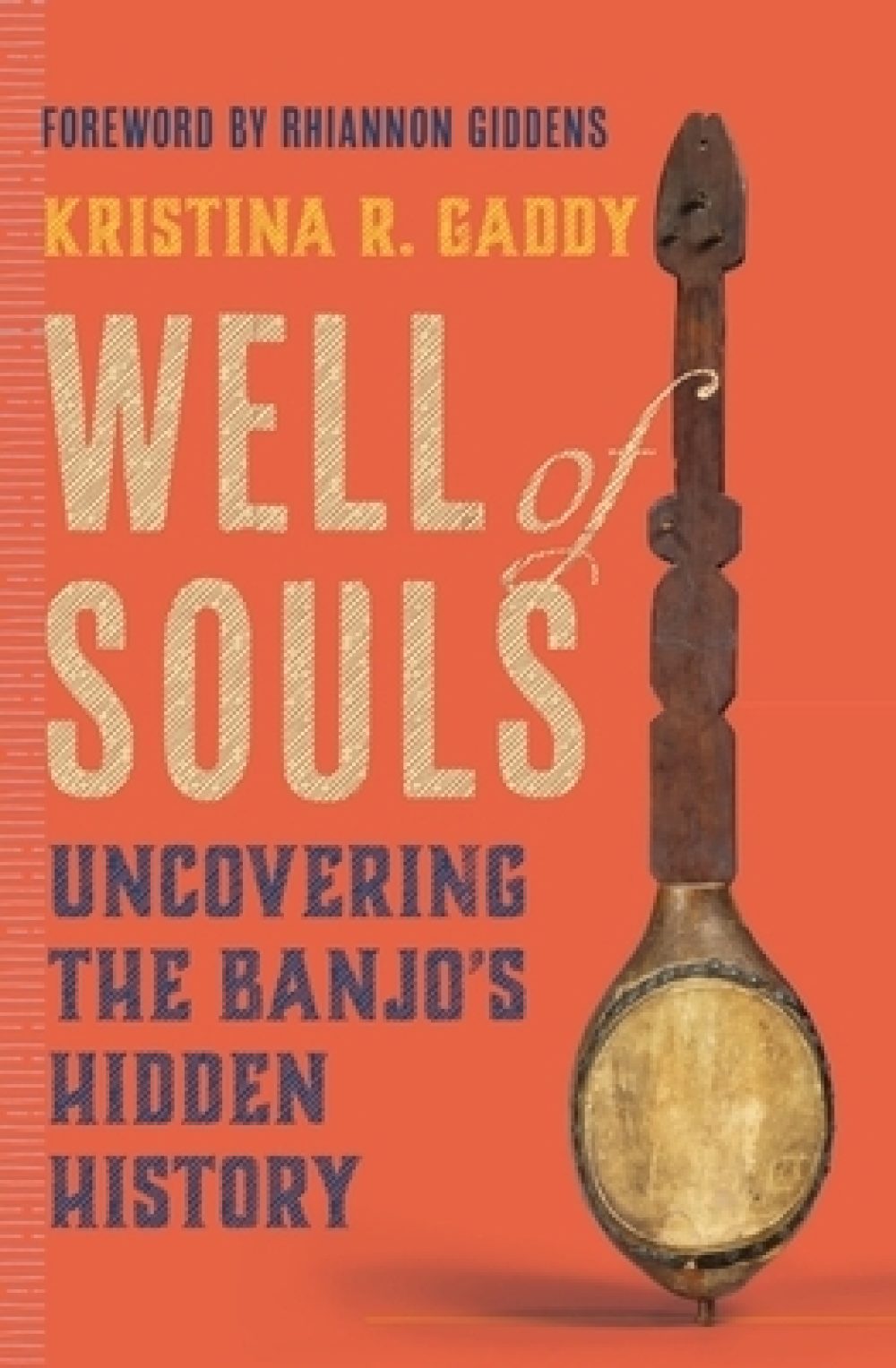

So I put all of that together feeling like I'd done something very new, and then my friend Kristina Gaddy put out this book called Well of Souls (Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History) that talks about how in the early days of the banjo’s existence, it was traditionally played in a setting with two drums and for religious dance services. That was the thing. You go play the banjo and dance the kalinda. Those were the earliest expressions of Black Americans spirituality and culture. These are things that were not directly inherited from an African culture. They were invented here, and part of the spiritual underpinning of the community, and I didn't know that.

That was really where I knew I'd hit on something. I had tried to have original ideas and wound up re-creating this thing from hundreds of years ago but I didn't know had ever existed before. I can't do that and feel like, “Oh, this is just kind of by chance that I just happened to put these pieces back together in this way.”

I think it speaks to to some kind of cultural memory, some sort of deep archetype.

Definitely.

Tell me about the rapper Demeanor who makes these interesting interventions throughout.

Actually, I only met Demeter before our recent Tiny Desk concert. We had not been in the same room until that happened, so that was pretty funny. We did this work on the album remotely because it was the pandemic. We had known of each other because I know his aunt. She had played me a little bit of stuff that they had done together and we had had the chance to chat online. I knew this was a guy who's grown up around banjo music, who plays the banjo, who raps and who's in touch with all of the deep history that I'm trying to work with here. It would've been really easy for me to call a rapper and be like, “Would you put a verse on this album?” And then I’d have no idea how to work with this because the groove is so different. And sonically, it was hard. I have to say he did a great job putting together verses that just clicked. There was only one track where we had to do multiple approaches. The hardest part of it actually was figuring things out during the mixing stage. We're all very used to a rap vocal having a certain tone and timbre to it, and it didn't match the rest of the recording because I tend to work with really warm, rich tones and rappers into work but really crisp and sharp condenser mics.

So we had this whole thing where it sounds like it's from another place, and it was really interesting to have to develop a mix that could accommodate both of those things. It felt like meeting in the middle, rather than just slapping rap in a place where it doesn't really fit.

I can see that. It is an unusual sound one doesn’t expect to hear. But then, this whole album is already opening you up, to a different a different conception. Let’s talk about the instruments you chose to use. In the Songlines article, you refer to debates you had with your co-producer, Brian Slattery, about what would make sense in this context. I’m curious about how you ultimately made these decisions.

I think there were a few factors there. One of them was that I really felt strongly that I did not want to make a banjo record. I wanted the banjo to feature prominently because it should give them what the text is and what I'm working with, but I felt—as I know that other Black banjo players who I am friends with have felt—that the folk community can sometimes get really excited about seeing Black people doing that again.

Do you find that a little condescending?

Well, it's nice to be appreciated. I am grateful to be seen, but at the same time I was feeling very conscious, especially after the winning of Steve Martin Banjo Prize, about not wanting to be boxed into that. I can do a lot more than that, even though I like to play the banjo. So part of my feeling going into it was that I want to showcase the other stuff that I can do more strongly than that. This led me to prioritize certain things or bring things back. I hadn't played electric guitar in probably five years, and then I picked it back up for this record.

You play it in a very interesting way on “Didn’t It Rain,” which we’ll get to.

It was a really nice thing. I think the rest of it kind of revealed itself to me as I went, where to use the steel-string banjo, where to use the gut-string banjo. I really wanted to use fiddle a lot partially because I just I haven't gotten to do it as much and I like playing the fiddle. But also because I think for me personally, when I'm thinking of this music in a spiritual context, the fiddle is the thing that takes me there. Not the banjo. So it felt more honest to the way that I experience the music to really foreground that as an element rather than emphasize the banjo, even though I kind of felt what was expected. It was an interesting combination of things.

My co-producer and I got into the weeds about what instruments do the people in this context have access to. If they're living on this island refugee camp in a future where our society has declined from where it is now, they’re not gonna have Ableton on the laptop to trigger these sounds. But they’re going to have inherited music that is deeply affected by people who were producing songs that way, so we were deciding, “Does it make sense to have a real drum here?” O.K., maybe not. At one point we were talking about putting piano on some tracks, but where in the hell would they get a piano?

You don't think pianos are going to survive the apocalypse?

Well, I don't think any of them are going to get shipped out to that island. But, you know, we wound up in other situations where you know he was like, “Oh I want to make this beat by banging on a trash can lid.” And I was like, “I'm not averse to that but also, there is no future in which Black people don't make drums anymore.” We’re going to figure that one out one way or another.

History proves that.

Exactly. So it was a back-and-forth about what I wanted to represent for myself and what was realistic to the concept of the record. There’s a little bit of electricity but nothing digital and there are drums but not the drums that we’re used to, and there's a banjo but not the banjo that we’re used to, and that kind of thing.

Yeah. That's cool. I like that. So basically what you're doing on the musical side of things is making new arrangements of songs that you’ve found and that fit this concept. I'm curious though about some of the arranging choices you made. So let’s talk about a few songs. First, “City Called Heaven.”

This was actually the last one that got made. I love this song. I have heard it done a few different ways. Friends of mine who have learned from other recordings. But I actually didn't know that Fannie Lou Hamer ever sang that song. I was just listening to that record for something else and stumbled across it and found I just really love the melody that she puts on it. I don't know anybody else who sings it with that… [sings], that very dissonant interval in there. I knew I had to do something with it and I think from that point on, it was just a question of what do I have that fits this vibe? I knew that I could hear electric guitar, but then I didn't want to do very much to it because I like the melody so much. I didn't want to distract from it, so I decided I would put the electric guitar in, that I would play the melody, that I would use the chords to flesh out when I'm singing words, what was happening, and that I would put really minimal drums on it.

For some of them the task was to build on the song because the song is too simple to stand in a modern listening context. That's not what they were designed for. In this case my task was to stay out of the way.

I see. I guess one that would fall in the other department, and the one that I actually am using in our year-end program is “Once There Was No Sun.” It’s the song you end the album with. I should tell you that I'm not familiar with the original versions of any of these songs. Your knowledge of this music far exceeds mine, so I am experiencing them freshly. I really love this song, but here you’ve added a lot. You've really built up an ensemble sound.

The original recording of that comes from Bessie Jones and the Georgia Sea Island Singers. They perform traditional Gullah Geechee music, which has more of a drum thing happening than most of their songs. They also were not allowed to have drums at the same time as the rest of us were not, but they had work-arounds, like banging on the floor with the broom stick. Also, on those old recordings, they have this wonderful polyphonic clapping thing going on where people are just kind of inventing different clapping parts and different people are catching different ones. Throughout this album, my whole thing was trying to find a through line. I love the clapping. The clapping felt like that through line, because it's the thing that we're always gonna be able to do to accompany ourselves.

I decided to keep that. I changed the clapping. The pattern is different, but I kept it in the in the picture. I learned the song and then I went down to my producer’s house and I sang the song and stomped out the rhythm on the floor that I heard the kick drum doing, just kind of what I felt complemented the rhythm of the words. Then I went home and used my little midi sequencer here to just do a kind of rough where I built out some of the other parts in a very basic way and looped it, and started building the song. My co-producer actually owns the drums and he went and recorded the actual drums and obviously embellished on and improved my parts ten-fold while he was doing it.

I put the rest of it together, and this was kind of the the task of working with these old songs is that they're meant to be done communally by people who are all participating. You're not really supposed to sit and listen to them. They're not built for that. So I have that song “Once There Was No Sun.” I love it, but also there's kind of only one part to the song. You could argue that there are two short parts that go directly together, but it's the same thing over and over and over and it's not a long thing. I had to find other things to do in the middle, and the way that I did that was to respond to the rhythm first. The first extra piece that I came up with was a fiddle cluster thing [sings]. Then I put the banjo part on it and that’s a snippet of an old banjo tune collected from enslaved Africans in Jamaica in 1687.

I want to come back to that, but keep going.

Then I was listening to it and thought it needs something long to ground it, because right now it's all a lot of short sounds and there's nothing unifying it, and then I developed a string part. My string part creating process is extremely chaotic. I just sit down and I hear one part and I record that part and then I come up with another part that won't get in the way and then I record that part and so on and so on until I decide that I'm done. So it's an improvised string part, but it worked.

The result is great. You mentioned the enslaved Africans in Jamaica. Four tracks on this album draw from the song “Angola,” documented by this guy Hans Sloane in 1688. Tell me more about that.

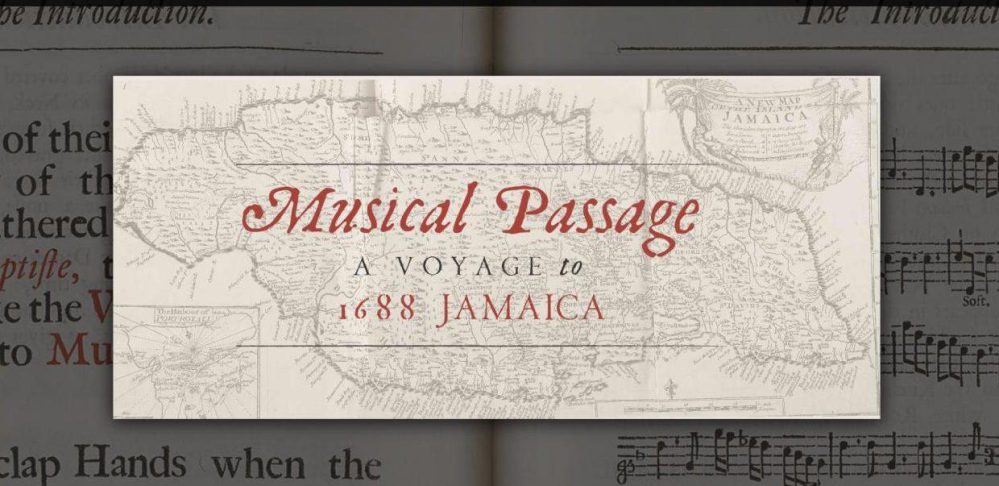

Right. So there was this man named Hans Sloane who was the personal physician to the governor of Jamaica, and he went over there with the intention of collecting different minerals and herbs that he felt had medicinal value that the British aristocracy of the time was not aware of, so that he could elevate his standing. He didn't do a great job as a physician. The governor died two years after he got there, but while he was there he did encounter some very cool music, and although he was not good enough with notation to write it down as he heard it, he was with an enslaved African man named Mr. Baptiste who could do that. Mr. Baptiste transcribed three pieces of music that they heard, one called “Angola,” one called “Papa” and one called “Koromanti.”

I've always liked “Angola” the most, so that was the one that I picked and decided to use. I forget what the original Hans Sloane text is called because it's just something like A Voyage to Jamaica and the year. Also, that story is told in much greater depth in Kristina Gaddy’s Well of Souls.

I will definitely check that out. But your source for “Angola” is a transcription done by this guy Baptiste. Have other people recorded the song based on his transcription?

Other people have used those pieces before. I don't know of anybody who's used “Angola.” There’s an instrumental phrase, and then a response by a vocalist. [sings] I wound up having to alternate the thirds because of what the chords were doing. So it kind of goes between major and minor and I made a very ambiguous harmony for the vocal response. I use that instrumental motif on the very first track of the album and then all the way at the end. At first you only get the instrumental motif, and then by the end I've added in the response in the voices. It’s meant to kind of grow into the piece as time goes by.

I don't know if you listen to much Rhiannon Giddens, but her song “Build A House,” uses a little of “Koromanti” at the beginning. There is a website called musicalpassage.org where they’ve made kind of like an interactive digitization of the transcript, so you can scroll through and it'll tell you more about what he was doing at the time, and then you can click a play button and somebody has recorded the part on gourd banjo or minstrel banjo. They’ve arranged with some percussion in some cases. It's very cool.

Indeed. Let’s talk about “Just As Well to Get Ready, You Gotta Die.”

I love that song. It's a blues guitar and vocal song originally. This is one where I made comparatively few deliberate choices as opposed to just following the music where it took me. I incorporated “Angola” again. In fact that's the most obvious interpretation of the song because it is the riff. It's everywhere in that song as opposed to kind of being hidden under things and creeping around in the other arrangements. Here, it's just, boom! we're doing it, and that's the only time when the strings play it.

I think in a lot of the cases here, I wound up learning the song and singing it, and then following where the singing took me. That was definitely the case in “Just As Well to Get Ready, You Gotta Die,”only it just took on a different flavor. I’m not sure why. That very poppy violin part, for example, is not a thing that I would've anticipated doing on this record, but it was just like, “Oh, that's what's happening. O.K., we're here.” And it fit. I don't have a problem with it, but sometimes the songs have their own ideas and you’re just along for the ride. That was one of those cases.

Let’s come back to “Didn’t It Rain,” the one where you really get into this dark electric guitar playing. What made you go that way with this one?

I learned that song from a Sister Rosetta Tharpe recording. I think the the word is out about her now. You know, I go to my shows and I say her name and people cheer and it's exciting that people know about her, but that's been a long time coming. She hasn't really gotten her due, and I think that as someone who is interpreting these old songs, and really with the goal of giving some of these bygone musical phenoms the credit that they didn't get it while they were alive—although she was of course very famous while she was alive, but not to the extent I would argue that she should've been—I knew I wanted to include something from her. I had a few different ideas about what it might actually sound like, and it didn't land where I expected it to. I kind of thought it was gonna be something a lot more similar to her arrangement of the song, and that I was gonna get some some guest vocalists and it was just gonna be us playing this Sister Rosetta Tharpe song.

Then Brian Slattery, my coproducer, got involved. He is the more free-flowing musician of the two of us. I have been bound up in the trad-folk world for so long that it’s sometimes hard for me to listen to a song and come up with a different idea for it, as opposed to just remaking it in my way. Brian is very good at changing them. So he was like, “Give me a minute.” This was one of the first two songs we started working on and he went and made this percussion part that's this very cool second line-like, thump and rattle locomotive vibe, and I love it. But then I was like, “O.K. this is really taking me to a different place.”

So then I made that drone that comes in and out, which is just me playing out of tune octave on a fiddle with a lot of reverb, and the rest kind of took shape on its own. That drone just took me to a very spooky weird place with the backup vocals, and that took me to a very spooky weird place with the guitar. I just decided to go for it and I think it wound up being a very sci-fi Sister Rosetta.

You did all this recording remotely? Even with Brian?

He lives in New Haven. I went down there a couple times because we were able to work outside on stuff, so there was a little bit of in-person there, but otherwise everybody who contributed was sending stuff in remotely, which was exhausting. I don't ever want to do it that way ever again.

Here’s something I thought of while digging into this album, the story part. Are you familiar with Narvaez expedition?

No.

It’s a Spanish expedition in the early 16th century aimed at establishing settlements in Florida. In the original group was a Moorish slave. They came with ships first to Haiti and then to Florida and just unbelievably horrible things happened to them: storms, shipwrecks, ambushes. It winds up being a smaller and smaller group of people until finally and they make their way across the southern United States and all these different clashes with various Native American groups, and finally only three of the original group survive, including this African, possibly the first African ever to set foot in North America. There's a great novel version this story called The Moor's Account, by Laila Lalami. But the circumstance that you describe reminded me of this story. They two are kind of bookends of the African experience in America. Back then, it was just completely terra incognita, and you are imagining a future in which it's all over. I think you’d dig that book.

Absolutely. I'll check it out.

O.K., here’s my wrap-up question. Were you surprised by the reception this album has received?

Yes. I kind of didn't think as many people would get behind it as they have. I mean, it’s a positive surprise; don’t get me wrong. But I think I expected a lot more people to be like, “What is he doing?” and instead I think their responses been more like, “Wow! What is he doing?!” People are excited about it and it's a cool position to be in. I was just talking to my friend Mali Obosawin yesterday. She’s doing incredible work with indigenous music, her own music from her perspective, which is indigenous, but it's not about her. Anyway, we were talking about how we both feel like we are doing the first iteration of what we're doing. She just put out this wild Wabanaki free jazz suite, which you should absolutely check out. It’s called Sweet Tooth. It’s on every year-end list right now. She’s killing it. But there hasn't really been folk Afrofuturism before, other than Toshi Reagon, and that's not a project that's being consumed in the same format, because it happens in theaters.

So it feels to me like I did break some new ground and I am excited that I was able to do that. But the reception has been really good and people have been very complimentary about it. I don't think everyone has gotten it completely yet, but I didn't expect them to. It’s something that's meant to take a little bit of thought and I think the way that we consume music these days isn't always conducive to putting in thought. It’s more about volume and it constantly being on in the background.

Right now I am thinking harder for future endeavors about how I might do a better job at making something that I can guide people in deeper, rather than having to be deep already to get there.

Well, it made the Transglobal World Music Chart. I voted for it. So clearly you’re appealing across boundaries. Congratulations on this project. It’s great to speak with you again.

Likewise. Thank you.

Related Articles