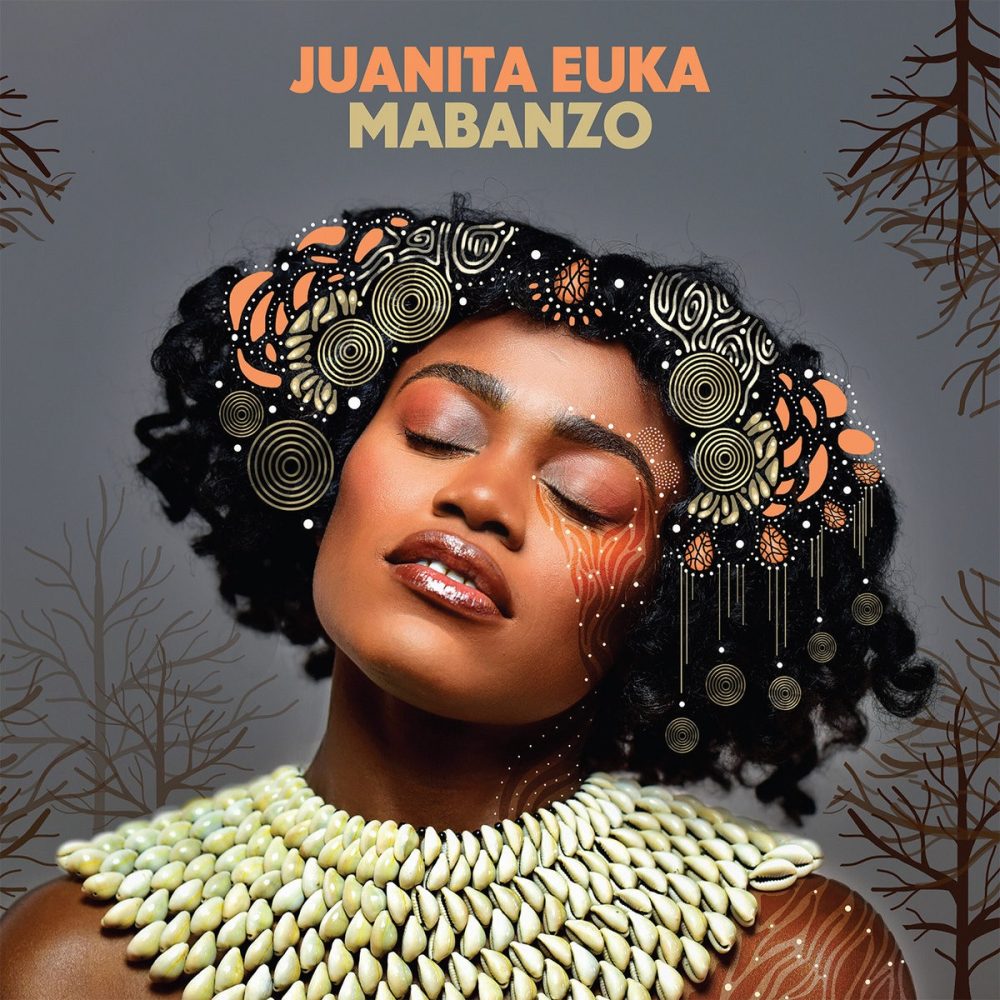

Juanita Euka is a Congolese-born, London-based singer/songwriter with a remarkably broad musical palette. The niece of Luambo Makiadi Franco—Congo music royalty—she lived in Argentina and made a deep dive into tango, later Afro-Peruvian music, and in London, Afrobeat and funk with the London Afrobeat Collective. In 2022, she released her debut album, Mabanzo, produced by guitarist Greg Sanders. The album spans funk, Afro-Cuban, Afrobeat and Franco-esque Congolese rumba with seamless ease, showcasing a voice and a talent we will likely be focused on for years to come.

Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Euka by Zoom to discuss the album and her unusual career story. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Juanita, this is a wonderful album. It's a grand tour of styles starting out funky, going deep into Latin music, and then venturing into the Congo sound. All of it's very well done. You have managed to make all these styles talk to each other.

Juanita Euka: I really wanted to celebrate my influences and the journey I've had with music, which I think is quite unique. I do love a lot of different types of African music, especially Congolese music, where I'm originally from. I love Latin music. That's been very close to me from early on in life. Moving from Argentina to London at the age of 14 was quite a shock. I was missing Argentina. I was feeling quite nostalgic. It's an age when you form your friends and have your little life. My emotions were all over the place, and I found refuge in music, especially when I had the opportunity to sing with Malambo.

Malambo was doing music from the coast of Peru, Lima, Afro-Peruvian music. We also did classic tunes, boleros and Argentinian tangos, which I felt very connected to. It wasn't just the music. I was living that nostalgia, that sentiment of missing another place. That fueled my musicality in ways that I was able to express myself in London. So that's how I ended up doing Latin music in London. That began a journey which led to my joining the band Wara, another Afro-Latin band in London, and developing myself more as an artist.

How did you get from Congo to Argentina?

My parents are Congolese. They traveled a lot because my dad worked as a diplomat, and as you know, being a diplomat, usually you are in a country for maximum of four years and then you move on to another country. We moved to Argentina when I was around two. We stayed there the longest because the situation in the Congo was very unstable, and my parents were not really sure what to do next. My dad and mom were already thinking about moving to London. My dad had family there. My grandmother was living in London. It was something that was easy for us to do because we had family to help us out in these really challenging times.

When are we talking about?

We moved to London at the end of 1997.

I see. Just as Mobutu was being driven out of power.

Exactly. Things were happening big time in the Congo. That was affecting our lives directly. We had to make decisions. We couldn’t go back. The kids needed stability. So coming to London was the best option for us at that time. This was a massive change for the Congo because Mobutu had been in power for many, many years. I was born in a dictatorship. My parents were kids of the colonies. So there had been so many different periods that Congolese people have lived through, and that definitely has impacted my life and my parents’ lives, and so many of the people around us. The situation and was really critical, and it's still a challenge today.

Of course.

So what can you do? You can find release or hope or a sense of starting life again. Music has been that thing that's let me find hope and be excited about life. It doesn't even really matter what kind of music. I really threw myself into that role of being an artist.

Tell me more about your life in Argentina.

My dad began his career working in Spain, in Madrid. He worked there many years before he married my mother. My mother and father had lived in Spain before I was born, so this assignment happened naturally for him because he could speak Spanish. So this was his next post. I've got an older brother, then I am the second eldest, then my younger sister and younger brother, and also another sister. We have different mothers. It's a big family.

It sounds like you left Congo before you could really form any memories there.

I don't remember anything. I was way too young. My mother would say that when we first moved to Argentina, I was somewhat fluent in Lingala. I don't remember much about that, but my dad was always encouraging us to speak French. He wasn't very keen on us speaking a lot of Lingala, at home.

And there was Spanish as well.

Yes. Exactly. So the way my life was as a child, I used to go to the Lycée Francaise where in the morning it would be French and in the afternoon it would be Spanish. And then I go home and my parents would speak Lingala, and I would answer in either French or Spanish. When we would travel, people would come to my mother and say, "Oh my God, your daughter. Her Spanish is very, very good." They didn't realize I had lived with that.

You're lucky. It's much easier to learn languages when you're young. But why did your father not want you to speak Lingala at home?

I don't know. I think he just wanted us to practice our French. French was the formal, official language of the Congo. He didn't want us to neglect that.

Maybe he thought it would open more doors for you.

I don't know. It was very odd, because as children we could understand Lingala very well. But then we moved to London and we were with cousins and uncles and they were speaking Lingala, they would ask, “Do you understand Lingala?” And I would say yes, but my dad didn't give us the habit of speaking it. It was very rare that I would speak Lingala with my dad. With my mom, it was easier. We could speak anything. It’s mad!

So when you moved to London, your childhood memories were in South America, not Africa. And you mentioned Peru.

That was another avenue I explored, but in London. I knew songs by Carlos Gardel and a lot of old boleros. I remembered those. They felt comfortable, and it was something I needed at the time. The Afro-Peruvian music was new, but it felt connected.

It's interesting about tango. We did a program about tango some years ago with Robert Farris Thompson, and that program connected the music with its African roots, tracing back to the milonga. When I actually went to Argentina, I found that that idea was somewhat controversial among some tango aficionados. Did you ever encounter that?

Yes. In Argentina, I was pretty much like any other kid, learning tangos. Then later I went through that same experience in London, singing milongas and tangos. People would be dancing tango and I would be singing. And then the more I was listening to that music, I started to realize that there was a strong African connection. Even the word tango. In Lingala, “tango” means “a moment in time.” It's kind of nostalgic.

Then a few years ago, I saw an amazing documentary about tango music by Dom Pedro called Tango Negro: The African Roots of Tango. In Argentina, like you said, some people do find it hard to understand the connection to Africa. But that film is really well made, the way that it connects the roots of the tango with the rhythms. The rhythms of the tango are very hard on the keys. The way the keys are being played. And I went even deeper with this history of Argentina during lockdown. I watched Canal Encuentro, a Spanish TV channel. It's only in Spanish but it's amazing because it talks about a lot of Afro-Argentine people that contributed to the music, and the culture of Argentina. Many people don't even know. It was an eye-opener. As a Black kid that grew up in Argentina, it blew my mind.

When did you decide to be a musician?

It happened in Argentina. I grew up in a family where there was always music in the house, a lot of music. I felt connected to music without wanting to be a singer or an artist. But then it was partly my friends encouraging me to sing. One time we made a trip when I was in secondary school. I was around 13, just before we went to London. So we went on this trip. I went to a Catholic school and we went with school friends. All of us had to show something that we were good at. It was sort of an exercise. Some of my close friends were like, "If that girl can sing, you can sing.”

I decided to do something. I don't think my class had ever heard me sing, but I got up and they were my audience. I sang this tune in Spanish, and when I was done they all clapped. I felt really nice about that, so from then on, knowing that I loved music and felt connected to it, I decided firmly to become a singer. That's when I made the decision and never changed my mind.

At home in Argentina, did you hear Congolese music?

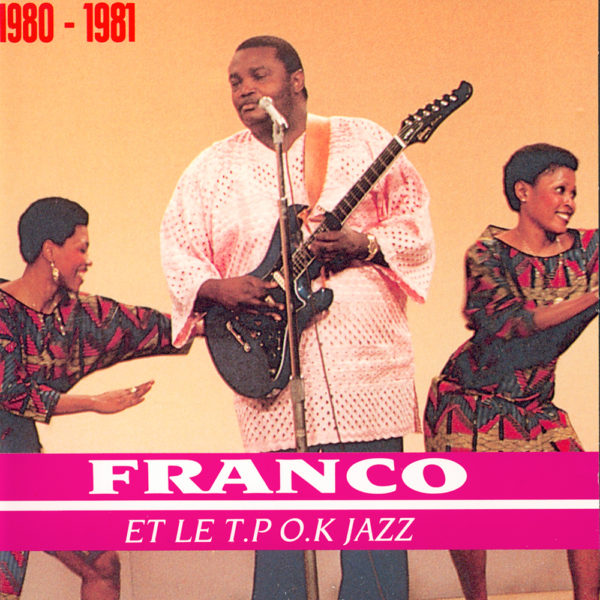

Yes. A lot. We had tapes of Franco when he used to perform back in the day in Zaire. Songs like “Massu” and “Mario.” He was very theatrical when he was on stage, talking to the audience. I automatically felt a lovely connection with my uncle's music. To me it was the soundtrack of my childhood, and also something that my parents loved, especially my dad, because he grew up with Franco. They were like brothers.

How does that family connection work?

Franco and my dad were cousins. They were teenagers together. All throughout my dad's early life, they had always been together. Recently we had this conversation, before lockdown, and he was telling me stories about how it was when Franco began doing music, and how the uncles, the Luambos, were very strict. They did not like music in the house. But Franco was determined to do it. He never gave up. He would just ignore everybody and do it. My dad wasn't as musical as Franco. He was more into things like politics and the world of diplomacy. He had different dreams.

But Franco's music has always been a massive part of my life. When he died, I was only five-years old. My mom always said, "Congo has always been in your life, even though you don't remember much." When Franco died we were in Argentina. I remember the early days when he passed away, my dad was really sensitive about it—the loss of his cousin, the loss of a great figure like him. My mother told me that the last house we had in Kinshasa was Franco's house. At the time, my dad didn't have a house and we had nowhere to stay. We had been traveling, and my dad was still building his career as a diplomat. Franco was kind enough to let us stay in his house for a year, before we moved to Argentina.

The house in Limité. I know that house. I actually met your uncle there in 1987. He was on his way to play a show out of the country, so I never got to see him perform. It was a very brief meeting, but I'll never forget it. My colleague, Sean Barlow, had interviewed him in 1985, and we recently made a podcast of that interview with Franco. Franco was the best.

Yes. What a figure to be related to. I'm still discovering more music all the time. To me he's always been a fountain of inspiration and strength in a tough industry. Every time I would feel like I was facing big challenges, thinking about my uncle would keep me going. There's that as well.

So you arrive in London at 14, Congolese music, boleros and tangos and all these things going on in your background, what happens? How does your music career unfold from there?

Well, my first challenge was to learn English. I had to get used to my surroundings. And that was a journey in itself. I knew already what I wanted to do, but it was quite a challenge for a young girl with African parents coming to London and wanting to do music. Looking back, I think I was pretty brave. You know, African parents can be very traditional, thinking that things have to be done a certain way. I had little rebel side in me. Not crazy rebel, but just wanting to do what I wanted to do.

Your folks probably weren't happy that you wanted to be a musician.

My father was always protective about it. I think he wasn't really sure. He couldn't understand. With my mom, always wanting to learn, and wanting me to be happy, she was more involved than my dad was. When I arrived in London, I started going to dance classes. I wanted to develop that, and my dad did find that weird. He couldn't understand. It was funny, but then my dad was traveling a lot, trying to get back into diplomacy, he wasn't really around that much. I was mainly with my mom, and it stayed like that for many years.

I would say that this is been something I've been teaching them as I've become more involved and active in my art. So it's been a mixture. In the beginning, trying to get the dance lessons, get singing lessons, doing the things you want to do, you have to study and try to perfect your art. But at the time, obviously, I had all this background. I did find it hard to find my space in London. I started to discover jazz and other styles of music, r&b and hip-hop. In Argentina, you could find little places where you could get hip-hop records. My brother would go and get CDs. But I expanded that a lot more in London, and I started to think I could do more. “I can do that. I can do that. I can do the other thing too.” It's always been like that with me.

That comes through on this album. Is this your first album under your own name?

This is my first as a solo artist. But I've been involved in recording with Wara. That's the band where I met Greg, who produced this album. Greg played guitar in Wara. Eliana Correa wrote the songs. I met Eliana when I joined the London Lukumi Choir. so there was a whole chain of events in my musical journey that led me to Wara. This is a band that fused Afro-Cuban roots with other Latin sounds. There was a little hip-hop and jazz in it too. Josh Solnick rapped in English, and then we sang in English and Spanish, so the music connected Afro-Cuban with hip-hop and jazz.

Well, it helps explain how you got into so many different styles. So let's come to this album, your solo debut. What was the idea? What was your goal?

I don't how to answer this. I wanted to show myself as an artist. I wanted to show my influences, as much as possible, all sides of me. I felt like if I'm showing for example just the Latin side, then you don't really know who I am. If I should show my ability to sing in English, then you don't know I'm Congolese. Showing my Congolese roots was really important. That's where I’m from, although I've never lived it properly. Circumstances didn't allow it. I guess I just wanted to present myself to the world. This is me.

And I have the greatest support for my music with Greg Sanders. He was able to push things even further musically. We also got to highlight the community of musicians in London. Throughout this 10 years and I've known Greg and worked with Wara and other groups, with Malambo, there's been a chain of musicians that I've met in London who could play any type of music. So it’s a mixture of things, and also a chance to tell little bit of my story. If it wasn't for Argentina and everything that I absorbed when I was a child, I would not be the artist I am today.

Tell me a bit more about Malambo.

That was a project of David Mortara and Tim Sharp. They became very good friends and musical mentors for me. I had done a lot of courses, dancing and so on, and now I just wanted to become a professional singer. With this project, we explored the Afro influences of the coast of Peru, Lima, with styles like festejos and lando…

Beautiful stuff, which we first heard from Susana Baca.

Yes. So this project took me on a different route, I had never been to Peru before, but I felt I could sing that music. And I felt I was connecting with the African element of Peruvian music. I loved learning about the history of Peru also. For me, it was an example of what happened to Latin America, and all of the Americas, the result of the transatlantic slave trade and how traditions, music, rhythms, were able to survive. You have the same thing in Brazil, in Cuba.

It was becoming a crazy trip. “What's going on? Everything that I pick has to do with Africa, and I'm African myself, a Black woman.” It was very rich, and very human. When people listen to this music, they come alive. They’re happy. I think Afro-Latin sounds have been able to survive because of that. If you can survive all that, you can survive anything in this world. I could go on forever about this.

I relate. Because this is the territory we explore in our program. In the Caribbean and the Americas, it's always a mix of European, African and indigenous cultures, but the mix and the particulars are different in every case. It's endless.

Absolutely. And I was going through a journey myself, but I'm able to see that other people were having different journeys, parallel to mine. That’s how a song like “Suenos de Libertade” came about. For very long time, I could understand the Latin American experience as much as I could understand my Congolese experience. For me it was parallel, the fights for freedom. Unfortunately, people go through harsh experiences, but still able to fight for their rights. I find that really powerful, how Argentinian people have always been that way. Going to primary school, I remember that a lot of the artwork in school was local. The teachers would say, "We don't want anything from America. We want Argentinian." It was very patriotic. We don't want to lose ourselves. We have to know who we are.

That inspired me to be who I am as a Congolese. Because we came from a dictatorship, we were not allowed to speak certain things. People now are more open about what they think and what they say. And people learn from history. "You know what? We are can have this." Social issues and politics mirror each other. We want to find that spirit and that will to fight against any kind of oppression, people trying to beat other people down. That sentiment is very strong with me, that's why I wrote that song.

Tell me about some other songs.

In “Camarades,” I wanted to speak to all the Congolese people like me, people who had their own experience of leaving Congo and living abroad. I’m talking to the diaspora, but at the same time saying that even if you're not from the African diaspora you can relate to the struggle, being abroad and trying to sort out your own life and build things. I'm just saying my story, but also trying to find that brotherhood and sisterhood with my Congolese people.

That song really feels like Franco, that easy 12/8 rhythm and feathery chorus guitar.

Yes. Yes. That was very exciting because I was able to build references. Obviously there's the story in the song, but then in the music there's a strong reference to my uncle, and the way that Greg played the guitar line—I listen to it, I just want to cry. It sounds just like Franco. My cousins were crying, crying with happiness and also feeling that connection that Greg was able to capture. That beat is from one of my uncle’s tunes, “Kimpa Kisangameni.” He’s singing in Kikongo, singing to his mom. It's a completely different subject.

I love that song.

It's such a great tune. He’s so emotional singing to his mom. “I don't want you to lose another son." He's talking about his brother Bavon Marie Marie, who died in a car accident. I felt like that beat needed to be in the record. It's important not just to have seben all the time. With Congolese music, it's a lot of seben, which I love. Kofi Olamide. Fally Ipupa. All of you are amazing. It's great. But there's more too. And with Greg it was so easy. “O.K., let's do this.” I was glad we were both really up for it to create a song like that.

It certainly perked my ears up.

Then “Alma Seca,” the lead track. That was a highlight of my connection with Cuba. Also “Bano de Oro.” In Cuba there are so many different sounds. I wanted to celebrate that. I like songs that are quite dramatic. So I wanted to create songs where I could say I personally have been through it. “Alma Seca” is kind of a bittersweet tune.

What does it say?

Well it means “dry soul.” It's a heartbreak tune. You know Trio Matamoros from Santiago de Cuba?

Sure.

They sang a lot of boleros, a lot of trova. I love the Cuban trova. I used to sing those songs at gigs, so I wanted to create something of my own like that. That’s what “Alma Seca” is. With “Bano de Oro” I tried to connect Congo and Cuba, going back to when Cuba connected with Congolese people in the ‘40s in ‘50s. Congolese people at that time were inspired to create modern Congolese music. To connect all of that in one song was a challenge. In a way the whole album has that element.

Greg and I were able to just focus on the songs, but underneath the songs, that reference is intact. I'm a Congolese who loves Afro-Cuban music, but basically that conversation in the music has been happening back and forth for a long time. “Hey, we’re still here, and we still love you, Cuba.” It's that type of vibe. “Bano de Oro” is like my ritual song. When I was writing the song with Greg, it was like a jam. We were free with it. In rumba, in Cuba, I find that element of improvisation very inspiring. That's the thing that makes the music of Cuba so beautiful and so powerful. They can go anywhere with the music.

But it's always within a structure. It's one of those situations where the structure actually makes you free.

We can bring down the music. Boom. And then you have the singer saying something, connecting with the people, like N.G. La Banda, one of the first timba bands in the ‘90s. The famous Buena Vista Social Club documentary connected a lot of people to that. But there's much more to Cuba than Buena Vista Social Club.

That’s for sure.

I saw so many bands when I went to Cuba. I've been there twice. It's unbelievably rich, all the way from trova to fast timba.

Let's talk about the song that you made the video for, “Nalingi Mobalite.”

“Nalingi Mobalite” was for me an opportunity to create a narrative with a female style of expression when it comes to relationships. I wanted to have fun with it. When we began doing this tune I wanted something danceable for the dance floor. I was just being myself with it. I didn't want to be like other Congolese singers. I love Mpongo Love, who was a soukous artist. In her music, she was very much a feminist. She had strong commentary about what was happening with Congolese woman, how a man would have more than one woman, and she just shared her frustration. That was inspirational to do that as a soukous artist. And also she used to produce her own music. So she's an artist I really admire. I felt like she gave permission. Why not sing a song about, “I don't want a man?” Why not?

In the video, you get that right from the start where you get a phone call and basically tell the guy to get lost. “Don't call back.”

The powerful thing about the visuals is that you can add more layers to what you're trying to say, so people don’t just read a book by its cover. “I don't want a man.” Boom. There's more to it. She is restrictive. This man is not good for her. And also, I'm having fun with it. It's important to have fun and not hold on too strongly to those difficult moments when you go through a heartbreak. When that happens, your whole world is falling apart, but you just have to shake it off and say, “You know what? Tomorrow can be a better day.” The song and video have got that hope, and wearing that sapeur outfit felt really good.

Yes. That outfit makes quite an impression.

I just took that social movement from the Congo and worked it into my narrative. When my stylist dressed me with that suit, I literally cried. I've never felt so elegant in my life. So there's that idea of taking power back is a woman, and as a human being. So you can have fun with it, but it's also a powerful message of resistance and female power.

Here's a philosophical music question. I've been working on a documentary idea about funk music in the ‘70s in Africa. It sweeps across from the funky bands in Nigeria to the golden age of Ethiopian pop with all those jazzy James Brown references. And it ties the evolution of music to the politics of that time.

I love that.

But we've had this interesting discussion when it comes to the Congo. There seems to be a tension, to put it simply, between rumba and funk. Rumba reflects the Cuban influence that underlines Congolese music, and funk reflects the American influence that was so strongly felt in Nigeria. There's this idea that the rebellious funk music of Fela in Nigeria was suppressed in the Congo for political reasons. But a Congolese man I speak with who knows the music history well says it had more to do with the colonial experience. Congolese, not speaking English, did not relate as much to the American sound as to the Cuban sound, which had strong echoes of their Bantu culture in the percussion.

I was thinking about this as I listened to your album, and I was really struck by the opening track “Alma Seca,” which to my ear is super funky, but it's also clave-based Cuban music. Somehow you've managed to marry the two very effectively.

I'm glad you were able to see that. Because with London Afrobeat Collective, the band I've also been working with for a few years, we've explored that funk side, African funk, which I find to be very important as well when it comes to African music. Parliament Funkadelic with George Clinton. To me all that type of music leads to people like Prince and James Brown I know that for Congolese people at that time, for example my mom, she knew about Fela, and how big he was in her era. People she knew used to go and see Fela in in Nigeria. But others were afraid. We were living in a dictatorship. Mobutu was such a scary guy. People were afraid.

In those days, Mobutu controlled everything. In Argentina, in our living room, we had a picture of Mobutu. Every Congolese government employee had this. My dad worked for him, so we grew up thinking, "Who is this guy? Oh, that's our president, apparently.” But it’s such an interesting point when it comes to funk, that liberation part of it. You know there’s a band in Cuba now called Cimafunk, combining timba and funk.

I've seen that band. Absolutely amazing.

So in Cuba they’re exploring funk. So there you go.

I find it so interesting that the idea when Nigerians heard James Brown and funk, they heard African music coming home. Same thing for Congolese when they heard Cuban music. But when Congolese people heard funk music, they heard it as American music, not African music coming home. I'm sure that's oversimplified. But to the extent that it's accurate, it's really fascinating. To some degree, aside from all the politics, it's simply a matter of the language and culture of the two different colonizers.

I remember my dad, when we moved to London, and he knew that I could speak English, and he asked me to translate for him what James Brown was saying. That was kind of awkward. “Dad, I don't think you really want to know.” James Brown had such a strong persona, and a very powerful band. Every Black person in Africa connected to it, just the power of it. But I think the Congolese had more of a sweet spot for the Cuban music, the romance. That was something they felt connected to.

Let's come back to your album. Tell me about the musicians.

Greg and I had worked together in Wara. It's been over 10 years since we first met. And through the years, we’ve connected with a lot of musicians. Greg has his own band too. So the way we did this, we were working remotely because of lockdown, and we were able to select people that could record the music and deliver it. With songs like “Alma Seca” and “Mboka Moko,” we had done productions before. This is music we had been working on for a long time. “Nalingi Mobalite” was the first song I produced with Greg, going back to about 2015. I knew I had a good thing. It was just a matter of finding the right people and the time to make the record. We were all doing so many different things. The opportunity hadn't really been there. But we knew we would do it when the opportunity came. In a mad way, lockdown gave us that opportunity.

You sure wouldn't know this was recorded remotely. It feels very present and tightly integrated. So now if Covid were suddenly gone, could you take this music on the road? Could you put together a band to play this live?

Yes. The great thing we are doing now is smaller sessions. It's been great to get people to play the music using musicians who recorded on the record. We come from a community of friends and musicians who love what we do. It makes it easier because it’s kind of a collective thing where we love music and we love playing with each other. The musicians would be there if there were gigs.

Well, I hope that happens. I'd love to see this on the stage. Thanks so much for talking.

Very lovely to meet you.

We will stay in touch.

Related Audio Programs