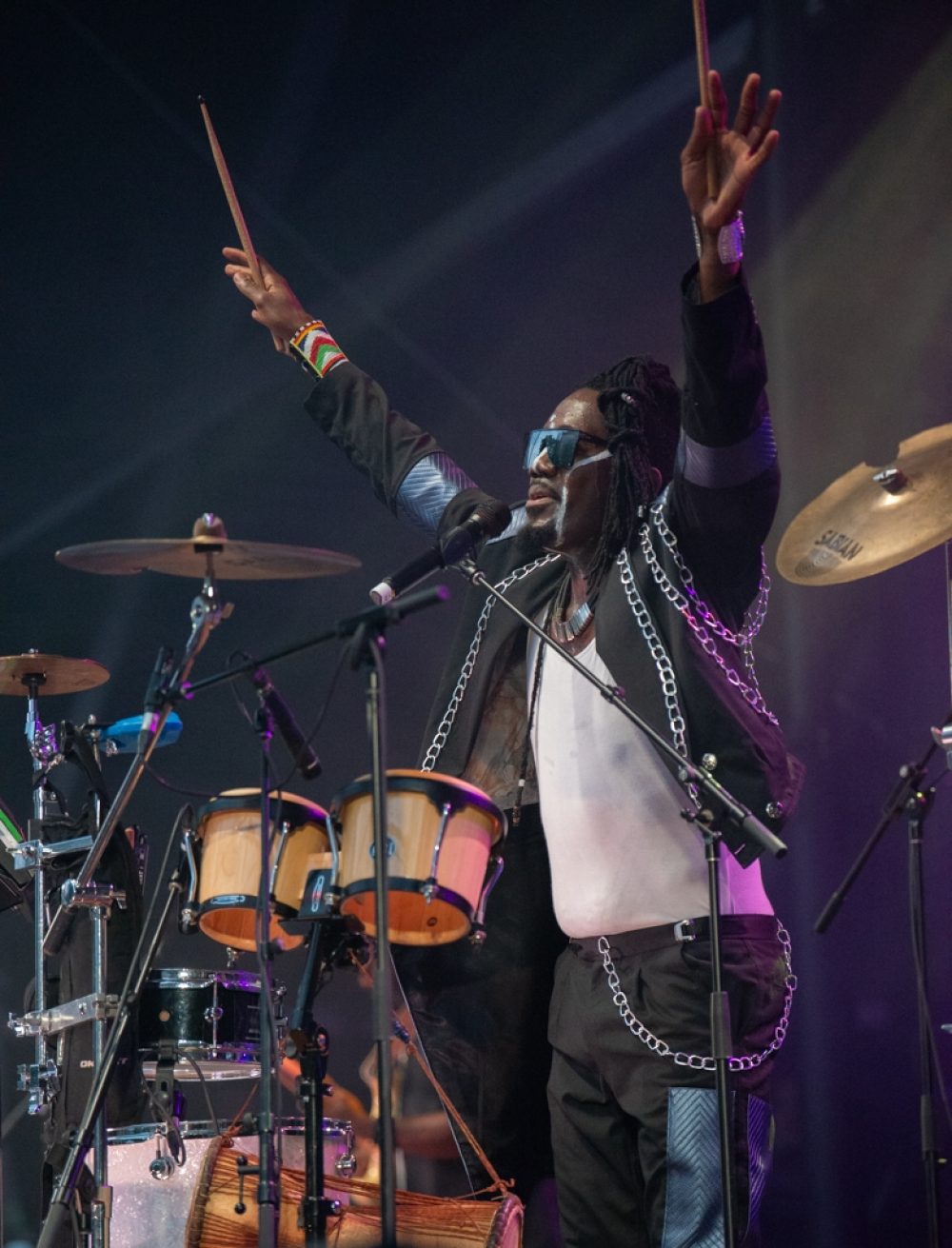

Lionel Kizaba belongs to a cadre of free-thinking African diaspora musicians animating the vibrant global music scene in Montreal. Born and raised in Kinshasa, Congo, he came to Canada in 2011 and has pursued a self-directed career ever since, blending a fascinating array of influences and experiences. On stage, Kizaba is a dynamo. A frontman with a towering ensemble of percussion instruments before him, he sings, dances and delivers a tidal wave of rhythms unlike anything we’ve heard before. Kizaba has just released his third album, Future Village. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached him in Montreal to hear his story and delve into this singular set of songs. Here’s their conversation.

Banner photo by Banning Eyre.

Banning Eyre: Greetings, Kizaba.

Lionel Kizaba: Hey, Banning. How's it going?

Very well. I’ve been listening to your album, which is quite amazing.

Thank you. I’m happy to hear that.

We will talk about is. But first, you and I have never done a proper interview. So tell me a bit of your story, how you became as musician and how you arrived in Montreal. What are the origins of Kizaba?

OK. Well, it started a long time ago. I come from a family with five children. Now we are four. I lived with my parents, but they both died when we were young. We left to live with my grandmother. That's where music was born in me. My parents died when I was six years old. I lost my father, then I lost my mother. I already some of talent in me. I used to play on the table. I hit the utensils on my plate. I played like a drummer. My mother said, “Stop doing that.”

This is in Kinshasa?

Yes, in Kinshasa. When my parents died, I went to my grandmother. She was a percussionist and a singer of traditional music. She also sang in a choir. That's where I started to see how to play percussion, and she invited me to play with her. I learned the love of music with my grandmother. I started to make percussion instruments myself, because I didn't have money to buy them. I made a drum with a casserole pan; I made a kick with pieces of wood. My uncle, the older brother of my mother, was a jazz musician in Chicago, and a professor at Howard University, François Mantuila Nyomo. When he arrived in Congo, he saw my talent. He taught jazz, blues and music history at the University of Kinshasa. He made me his drummer and trained me in jazz.

I started like that, playing jazz with my uncle. I played with him for several years. After awhile, I wanted to learn Congolese music and I played with artists like Ferre Gola. My uncle didn't like that. He didn't like that I wanted to learn Congolese music. He wanted me to play only jazz. But I did my own thing. I learned traditional music thanks to my grandmother. By the way, on my album Future Village, I do voice imitations of her. That's a tribute to my grandmother.

So I started playing rumba with Ferre Gola, Kabose Bulembi… I played for several groups in Congo, and then I created my own jazz group where I combined the traditional music that I learned from my grandmother and the jazz that I learned from my uncle. I had a band there called Jazzmobile.

How old were you then?

I created Jazzmobile when I was 15 years old. It was seven musicians. We had a struggle because life was so hard to live there. Without my parents, nobody could take care of me. So I made my living with music. I played gospel. I accompanied several people, and with the money I earned from music, I opened a small shop where people came to buy food, and that's how I lived. My aunt, Madeleine Ntoto Nyomo, my mother’s older sister, who lives in France, paid for my studies. All the school supplies, the little things, I paid for with my music. My two sisters and my two brothers helped me too. We were always together. If I make $100, I would take $40 and give $20 to my sisters, $20 to my brothers. We lived like that.

My older sister was a model. She was partying with everyone. If she earned $100, she shared too. She gave me $20 and my brothers $20. Before we were five, two girls and three boys. But then I lost my older sister. She had meningitis. That's what I talk about in my song, “Yembelaye.” At that time, I was really discouraged about life. I had lost my father, my mother and my sister. That was a lot to bear. I stopped believing in God. It was like God didn’t exist because we prayed when they were sick. We didn't want him to take them, but they died anyway. So I asked myself: does God exists for real? Because we prayed, but it didn't work.

What is the translation of the word Yembelaye?

Yembelaye means “sing for them.” It's a tribute. I sang for my father, my mother and my sister, who died in 2004.

Wow. That’s tough.

After that, I left the country. I was tired of staying in Congo. My friends, the ambassador, everyone told me, “With your talent, you have to leave here. You will never succeed here. You have to leave the country.” I almost moved to Germany. They told me Germany was good, but it was better to go to Canada. I had friends from Canada, so I moved to Canada on October 11, 2011, and continued my music. I was really motivated. Thanks to my uncle, I knew how to talk to people. I was already dynamic. I learned all that from my uncle. Then I made business. I went to see shows, I went to see a documentary about the Congo, and there I met a Quebec singer who was also a film actor. His name is Mario Saint-Amand. He sang and played blues. I had played blues with my uncle: 12-bar blues, jazz, swing, contemporary experimental jazz. By then I was 18. I showed him my videos on YouTube. He watched and called me the next morning.

He said, “Listen, I have a tour and I need musicians. Can you find me a pianist and a bassist?” I said, “Yes, I'll find you that.” I called friends I met here in Montreal. I had done a training for professional newcomers. This shows you how they subsidize music here in Quebec. I met my bass player there, and there was also an immigrant who came from Argentina, a pianist. I saw his profile. “Oh! He's a good pianist.” So I called and said, “I have a contract for you.” I called Mario Saint-Amand and said I had found musicians. We would be four on stage. We started rehearsing and he loved it. Then we did a tour through Quebec with 37 shows.

Then I accompanied other Quebec artists like Sébastien Lacombe. He is also on the new album with me; we made the title song together, “Future Village.” I also played with other rappers, like Quebec artist Manu Militari. I accompanied many people here. Then I focused on my own project. I created Kizaba. The first album, Nzela, came in 2017. Nzela means “path.” So I wanted to start a new path in Canada. Then I released Kizavibe in 2022, and now Future Village. I started working on this album in 2021.

Your sound is very unusual. It’s not like any Congolese music I’ve heard before. How would you describe it?

I would say it's Afro-Electro-Pop music. There are a lot of influences. There's the roots side, where I imitate traditional voices. I do it with my throat. (sings in a high, strained voice). Then there’s the pop. The first song is called “Fumu Na Betu.” That means “the ancestors of our country.” So here I'm talking about my grandmother. I'm talking about the ancestors, opening the door for me. The second song is “Sapologie,” which speaks about Congolese culture.

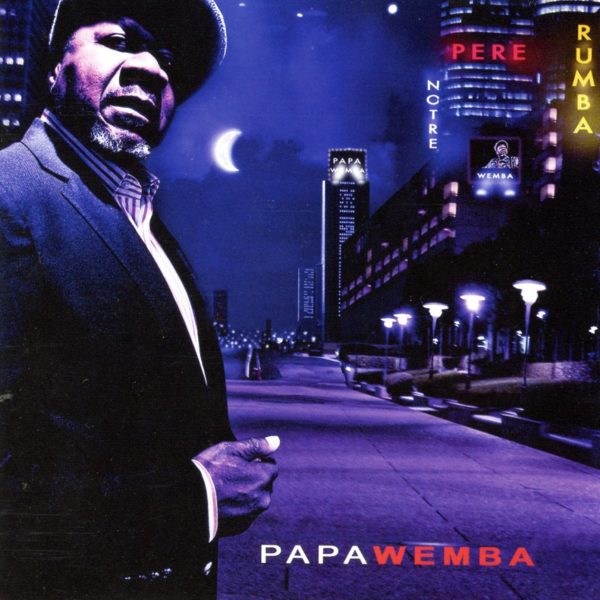

Ah ha, you mean the sapeur,(Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes or Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People), this culture of stylish presentation, championed by Papa Wemba.

La sape, voila. I grew up in Papa Wemba’s neighborhood, Matonge. I lived there for a long time. Papa Wemba inspires me a lot.

He’s one of my all-time favorites. The creator of Village Molokai.

Exactly! That’s my neighborhood. “Sapologie” is inspired by Papa Wemba because I grew up in Matonge. We love to dress up. I'm talking about this culture. There’s pop music in the sound there, and there is the roots, a little bit of Afrobeat, and Congolese guitar at the end to give the vibe. So that's it. I would say it's really Afro-Electro-Pop.

Let's talk about some of the other songs. First, tell me more about “Fumu Na Betu.”

That's the opening. I call my ancestors; I call on my grandmother. I say, “With this album, give me the chance. I want the light of my ancestors to open the door.”

I have ask about “Les Eglises de Kinshasa,” the churches of Kinshasa. We played this song on our podcast Planet Afropop.

Nice.

George Collinet, our host, has been to Kinshasa many times, though not recently. He said he didn’t recall many churches in Kinshasa. He said he was more focused on beer and music at the time.

(laughs) Well, “Les Eglises de Kinshasa” tells a story that I lived through in Congo. When I lived there, I played gospel in the churches, so I know there are good pastors and bad pastors. Some do that just to make money. The population is very poor, and in Congo, there is lot of corruption. It's a country with lot of money, a lot of mining. The government sells mining rights to the West. They take the money and keep it for themselves. They don't share it with the population. So the population is very poor. And it has created a lot of churches. Each district has at least five or ten churches. So all the pastors do this business.

Anyway, my brother works in a delivery company. He delivers food to houses. He is a bodyguard for a rich pastor in Congo. One day he stopped with his delivery car to put the gas in the tank. He went inside to pay and when he came back his bag was stolen. They broke the window, they took his bag with $2000 U.S. in it. So he called me. My brother is married and has three children, and sometimes I send money to the family to help. But he called me crying and said, “They stole my company's money and I don't know how I'm going to repay it. The company gave me 48 hours to pay back the money. Otherwise, they will fire me.”

I said, “I have to pay for my apartment, pay for my music studio, pay my credit card. I'm really in chaos.” I said maybe he could ask the pastor to help him get some money. He went to the pastor and the pastor said, “I will pray for you. God will help you.” He didn't even give one single dollar. When my brother called and told me this, I was really angry and sad. Here is this rich pastor, and you are his bodyguard and he couldn't help you. I said, OK. I went to the bank and borrowed money and sent it my brother. I have a lot of problems myself. I manage everything over here. But it's sad what happened to him. He paid the money back and I said, “No. I have to write a song denouncing the churches of Kinshasa.”

My sister agreed, “Yes. You have to write a song about the churches of Kinshasa because there are too many of these corrupt, false pastors. You have to denounce that.” So I wrote this song.

That’s heavy. I know this is a real problem, and it's not unique to Kinshasa. This is happening in Ghana, Zimbabwe, lots of places. Many pastors take advantage of the poor with false promises and get rich that way.

That's it. In all of Africa. It's serious.

You have a song called “Congolese Musique,” but to my ear, it’s kind of a rock song. What's going on with this one?

Exactly. Yeah, yeah, yeah. This song is about influences. I have lot of jazz influence from my uncle, and traditional from my grandmother. I use that in the introduction of “Congolese Musique.” I imitate those traditional voices, thinking of my grandmother.

You use a lot of different voices on this album.

But also, I had listened to pop rock and I understand that people love rock in the United States and Canada. I started playing this song in 2020 when I played at Mundial Montreal, and people really loved the song. In fact, “Congolese Musique” is also about the influences that we have brought to Africa. Congolese guitar is very special. In the time of Mobutu, he sent Congolese guitarists all over Africa, to Chad, Burkina Faso, many African countries to give lessons in Congolese way.

Sure. Tanzania and Kenya too.

Mobutu really valued Congolese music. You know, Afrobeats was born out of rumba music. Coupé decalé was born out of Congolese soukous. We call it the seben, in Africa we call it the soukous. So Afrobeats, coupé decalé, even salsa comes out of Congolese music. All these styles were born in Congo. That's what I say in the song. Congolese music has traveled so much. We have shared music everywhere, but we don't talk about it. We remain humble.

Your song “Bas-Koko” has an almost industrial sound. The guitar roars like an engine. Wow. Strong stuff!

Exactly. Koko means our ancestors, our grandparents. So this was about my grandmother and my grandfather, and the respect we have for our grandparents. In Africa, our grandparents live with us when they are old. When they go to the toilet, we take care of them; we wash them; we do everything. We have so much respect for our grandparents. I also about sing about Simon Kimbangu (Congolese Protestant cleric who founded a religion there in the mid 20th century).

Ah, yes. A fascinating man.

I respect his universe and what he did. I pay homage to him in this song. This is the other song I I played at the Mundial Mondeal in 2021. And the director of the New Orleans Jazz Festival was in the room. She saw my show, and it made her crazy. She said to me, “I want you to open Jazz Fest at New Orleans.” So I did that in 2022. I played the New Orleans Jazz Fest opening. There was Lionel Richie, CeeLo Green, Foo Fighters, Erykah Badu, and me! I was very happy.

I bet you were. Your song “Kitoko” is kind of funky one. It’s a dance song really.

Exactly. It's a love song. I talk about women. I call them “poussin.” Poussin refers to a baby. But you can call a beautiful woman poussin. In Africa, it’s like “my baby.” So I talk about love and the affection of a couple.

Let’s talk about the title song, “Future Village.” It’s an interesting mix. It starts out very slow, but then there’s this super-fast, kind of speed-metal part that comes in. And you sing in English. There’s a lot happening in this song.

There is. In “Future Village,” we find the traditional roots music, and we also find dubstep electro at the end. It's about the future, my future, but in the introduction, I'm talking again about my ancestors. I tell my ancestors I don't want to live in darkness. I want to follow the path of light. I say, “Help me to move forward in the direction of light and help light the future for all the African people, for all the people where there is war.” I talk about freedom for Africa and for Congo, where people are really suffering.

I see how people suffer in Congo. Today, when I talk to Congolese people, they say, “We have to give flowers to our country.” But if we just give flowers to our country, the country will never change. We have to stop talking like that. We have change the country, talk about what is wrong. We have talk about corruption, corruption in my country, and in all of Africa. There are minerals in Congo. But with the experience I’ve had in Canada, if I was a president, I would use that to create jobs. I would find trucks for recycling, collect the plastic people throw away to create other things. This would create jobs. We would not have gangsters on the road anymore. We would not have the shegue (street kids), children abandoned on the street.

The roads in the evening are violent. They will take your bag, your phone, because there are no jobs. Why are there no jobs? Because the government takes all the money for themselves. When people enter the government, they get crazy salaries. They get salaries more than a president of the United States. When you look at the salary of an African earning more than a president of the United States, and ministers that have salaries more than ministers in the West, that’s why I say, “Freedom for Africa.” The people are suffering. We have to vote. Our leaders do nothing for us. Give us food. Create jobs. Develop tourism. Tourism will create lot of jobs for everyone.

This is interesting, Lionel, because as you know, in Congo, especially during the Mobutu time, but even now, it's not been easy to sing a song like that. As I understand, you can't talk directly like that, calling out corruption and such. You need to be indirect, if you say anything at all.

It's not easy. That's why I'm talking about freedom for Africa.

You have the freedom to say such things because you're in the diaspora.

Yes.

But even the style of music you are creating on this album. In Kinshasa, it's perhaps more difficult to experiment like that, and to be accepted. The audience there have certain expectations, right?

That's it. When I made a song like “Sapologie,” they will love it. They will dance to it because the guitar that we play is soukous, and the bass. On my last album, there were more songs you can dance to, more coupé decalé and Afrobeat. That they will embrace. But experimental stuff? They will hear it and say, “Oh!” Even the musicians. They will say, “Oh maestro!” When I went to Congo to record in the studio…

You recorded this in Kinshasa?

Yes. My first album I did in Canada. The second, Kisavibe and Future Village, the new one, I did in Congo. I rented a studio and I brought musicians, traditional musicians, and everything. When they listened to the instrumental, they looked at me like I was crazy. They took me for a crazy person. The engineers said, “No, no, no, no, no, no?”

Even the engineers!

They said, “Here it’s not like that. This will not work.” I said, “Listen, this will work. Like this, like this…” This is the experience I got from my uncle. He always told me that jazz is going to change my brain. He told me that I had to play experimental jazz rhythms: 3, 5, 7, 6, 9... I played in all those rhythms. He told me, “When you leave Congo and go elsewhere, people will take you for a genius because you will mix that with the Congolese and they will not understand.” And when I was in Congo, people said, “He is crazy. He is sick.” (laughs) But my uncle would be happy. It’s thanks to him I did all this, so it’s a kind of homage. He died in 2010. He drank a lot of alcohol. He was a bluesman.

Fascinating. I suppose the song “Kimbala” is an example of that. It’s 12, as I count it. It’s also a very tuneful, funky number.

“Kimbala” is talking about a festival in a village. This is a rhythm from Congo we call kintueni. Kintueni is a traditional rhythm from my grandparents' villages, Bensi Bwesi and Bensi Kikaba, located in Bas-Congo. It’s a rhythm that traveled during slavery. In Haiti they call it rara. It also went to South America. That’s why I often play in South America because they like my music. They find it like music that traveled with slavery, but with the future side added.

So I start by talking about the party in the village. I talk about this kind of dance style in my lyrics. I played it for my friend Wesli, who is from Haiti, and he said he wanted to sing this song with me. He said it’s like rara. And then I understood. Yes, the rara is born from the music that plays in my village. So I sent him the trac and he recorded the voice.

Nice. Such a cool song. And that brings us to “AfroFuturisme,” another one that’s on the experimental side, right? And fittingly so.

Exactly. This is my own Afrofuturism, the way I define it. In fact, it's a movement that started a long time ago, back in the ‘80s. I want the future to be this kind of music that I make, this mix. One day, people will start to interpret the songs like that. I am showing a direction for the future of my music. I want it to be like a signature. “Ah, that sounds like Kizaba.” When I think of the future, the future village, I think one day Congo will be a country where there is no war and everyone will live together and have a good relationship with the West, a good union with the rest of Africa, a Congo where everyone has enough to eat well, and be in good health without cholera or malaria. Malaria is the disease that killed my parents. There will be lots of jobs. There will be tourism and employment for the Congolese people. It will be a future without racism where everyone can live together. This is my future village.

That’s great. You have to imagine the future before you can make it real.

You know, I spoke recently with Pierre Kwenders, another Montreal-based Congolese artist, whom I’m sure you know, and with and some other beat-makers from Lagos and Johannesburg, people who create the big hits for artists like Tyla. We talked about rhythms, and ideas about production. Maybe you know the producer/artist Kooldrink. He told me that his goal is to translate the African rhythms for the West. And he wants the big audience, 2,000,000 hits on YouTube and all that. But for Pierre, it’s all about the club, creating a mix that makes people dance.

It seems to me that you are in a way free frome these kinds of objectives. Your idea is more simply artistic, maybe more spiritual. And of course, Montreal has a certain openness, an ambiance that gives room for a music that is unique like yours, right?

Exactly. In Montreal, you need to have your own signature. When you are unique, they are more interested in you. When you are not born here, and you want to make music like the Quebecois, it doesn't work. They will say, “No, no. That's fake.” And then in my community too, where I come from, they also say, “No. We don’t want something new.” I actually want to make music that is not just for Africans. I want make music for the whole planet. I want everyone to come to my show and listen, and say “This is Kizaba!” I want my project to be without limits. In my music, you hear the electro, you hear the funky, you hear the Afrobeat, the traditional, you hear the pop rock. Everyone loves rock. I am a musician, drummer, singer, dancer… I give all my energy. I wanted to a concept that is really my own. This is Kizaba.

I’ve seen you perform, and it is all of that. Well, congratulations on the album. I hope we will see you at the Nuits D’Afrique festival this summer. Will you be playing in the festival?

Yes. Before Meiway on July 20.

Excellent. We’ll be there.

Thank you for the interview. This album talks about my life, about courage, about prosperity. I came here and I thought about where I should start. In Congo, I had contracts, I played in hotels, jazz every weekend, restaurants. But here, I had to start from scratch. It's the perseverance and courage I learned from my uncle. He told me that one day I will succeed. That's it. My dreams have come true.

Related Audio Programs