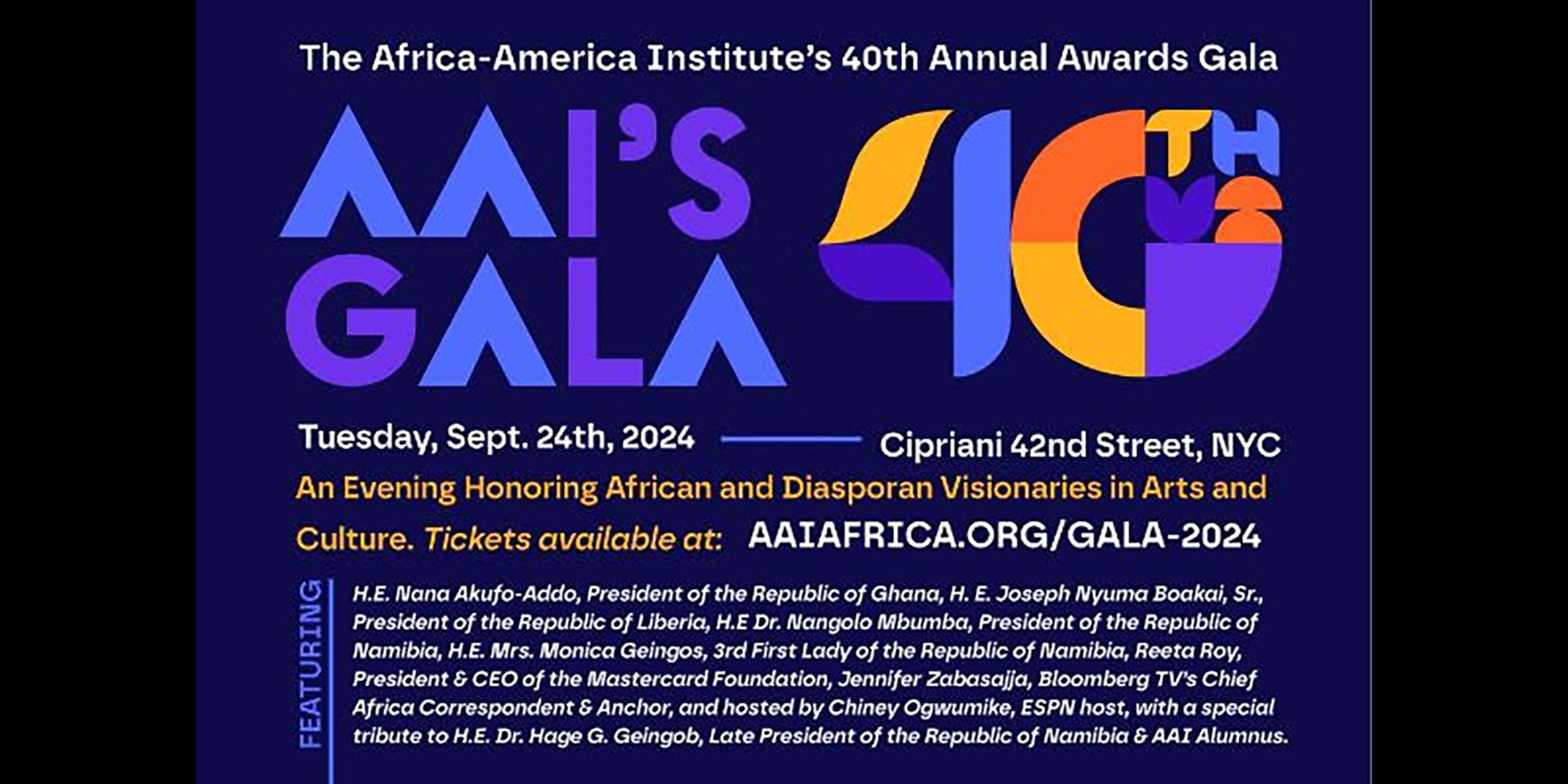

Kofi Appenteng is the President of the Africa-America Institute (AAI). Founded in 1953, AAI is a premier U.S.-based organization dedicated to bridging Africa and America by educating people and connecting worlds. AAI’s programs with leading universities have provided scholarships and fellowships to tens of thousands of students, and AAI alumni are at the forefront of Africa’s public, non-profit, and private sectors. Every fall, during the UN General Assembly, AAI holds a Gala in New York City to showcase outstanding success stories, and to rais funds and set the course for another year of fulfilling the organization’s mission. This year’s event takes place on September 24 at Cipriani’s on 42nd Street. Afropop Worldwide has worked with AAI in various ways in the past, notably providing music playlists for the annual Gala. Afropop’s Banning Eyre recently spoke with Appenteng about the organization and the coming Gala.

Banning Eyre: AAI started in 1953, and I'm thinking, man, that's before any of these African countries were even independent. What can you say about what the mission was back then? I'm interested in what it was like for people to start this organization at a time when all those countries were still under colonial rule.

Kofi Appenteng: It’s a fascinating question. And we've been exploring a lot of our history in greater depth because we we’re celebrating 70 years. I think that it was kind of a giddy time in terms of anticipation of what was to come. Just before our founding is when India became independent. African countries, especially the sub-Saharan ones, were starting to see that colonialism was on the wane and that if it was going to happen for a place like India, it could happen in Africa also. I think people thought that liberation from colonialism was inevitable, and this was the time to start building relationships between the U.S., the Caribbean, and Africa. A lot of African Americans felt that their liberation in the U.S.—which was still a project—was going to take some big strides in the ‘50s with desegregating schools and then in the ‘60s with civil rights and being able to actually vote, and getting rid of not just the rules, but the traditions that had kept them as non-citizens essentially.

Right. 1953 was before the Brown desegregation decision as well.

So our principal co-founders saw this and they got together with some kind of more institutional folks. William Leo Hansberry was probably the most visionary of the co-founders, and devoted his life to showing how if you really wanted to study Africa, there was a lot to study and it required more than just history. You needed to look at archaeology, anthropology and sociology, et cetera. There was a lot of rich history that preceded European domination during the colonial era, and preceded slavery. I think some foundations like Ford and Carnegie and Rockefeller saw that bond in Hansberry principally, but others also were onto something. And so that's how the African-America Institute started to get philanthropic funding. It was because of Hansberry’s and [Horrace Mann] Bond's relationships in higher education. That connected them to philanthropy, and then eventually business interests got interested also.

And then we were in the midst of the Cold War. So the U.S. government started to see this through that lens, and saw scholarships for Africans as something that could help them in their fight with the Soviet Union and to a lesser extent China.

I remember meeting people in Mali who'd gone to school in Moscow and we have other examples of that Soviet connection. Mukwae Wabei Siyolwe, who works with us now, grew up partly in Moscow because her father was an ambassador in the early years of the African National Congress. So I can well imagine that the U.S. would see things through that lens. But AAI’s goal was always education, right? That was the central mission.

I think the way to think about it is, not just education, but liberatory education. So not just knowledge for the sake of knowledge, but knowledge that would help one understand where one fit in the world, and maybe change one’s perceptions of the world. There have been lots of different ways that AAI has partnered with other organizations on this liberatory education journey. One of them was in the ‘60s and early ‘70s. AAI was one of the organizations that first introduced information about Africa into curriculum in K through 12 in the U.S.. Our records show a program called the School Services Program that got started in the mid-1960s and went through the late 1970s in its first iteration.

In 2020, we restarted that program in southeast Michigan. And it's now touching about 40,000 K through 12 students in southeast Michigan. The idea being that when you learn about the history of the world, you don't wait until the transatlantic slave trade to introduce the idea that Africa is there, and there are civilizations there. Probably you and I both got an education like that.

Right. We certainly didn't learn about Sunjata and Nubia. Obviously there's more African awareness now, but not enough. It must have been a huge change for the organization between 1953 and 1963 to have all those nations become independent. That must have been a very exciting time for the organization.

Yes, a very exciting time. People started imagining what it would be like if you had a world in which each African country was actually free and independent, and what that would do for the world. And I think that because of the Cold War lens and the desire for the U.S. to compete with the Soviet Union principally, but also with China, AAI started getting very significant government-funded scholarship programs. We were based in headquartered in Washington DC in those days, and what we started to find out was that because it was government money, some parts of the government felt that these were good recruiting grounds, basically for espionage, right? And so my understanding of the history is that the philanthropic organizations decided that it would be wise for the organization to leave Washington DC and come to New York and be further away from the government headquarters of government. They gave AAI some good institutional funding to enable us to do that. And then we were able to run the programs on our own terms.

Was it that being in Washington created a certain amount of pressure to be focusing on these Cold War-related espionage activities rather than the mission of developing education, trade, knowledge and the sort of higher principles of AAI? Have I got that right?

Well, I think that there was pressure on staff to kind of report in. Mora McLean, who's our institutional historian, has been doing a lot of research on this and could give a more detailed answer. But my sense was that the Africans understood that the Soviet Union was giving them scholarships because they wanted to influence them, and that the Americans were giving them scholarships because they too wanted to influence them. And they were very clear-eyed about that. But they also knew, once they had the education, they didn't have any obligation to pay money back. These were real scholarships. And it opened up the world to them. So they understood that bargain and also understood that nobody was their boss. I think that time in the late ‘50s and the ‘60s was when the pressure grew and the budgets were growing and we kind of made this move to emphasize our independence. I think this is one of the reasons why we're so trusted by Africans today. It was always very clear AAI was really trying to help the students, and it was working. It was not simply a branch of the U.S. government.

So we ended up doing scholarship programs for lots of different funders. The U.S. government ones were the biggest ones, but there must have been 20 or 30 different funders who did scholarships with us over that period of time.

When did you start with AAI?

In 2016 as president, although I joined the board about 16 years earlier. So I've had a long relationship with AAI. It's been a big part of my life.

Do you know how many scholarships have been sponsored by AAI over the years? It must be a huge number.

It's over 23,000 if you say scholarships and fellowships. And some of those people got more than one scholarship. So somebody might have gotten a scholarship to do a bachelor's and then also got one to do a master's program. So the number of people we think is around 20,000. And that doesn't include the work we're doing, for example, in the school services program, where, as I said, the schools we work with service about 40,000 students.

I know those fellowship and scholarship recipients have done amazing things, as I've seen in the various AAI Galas I've attended. Looking at where we are now with African governance and development, compared with what was happening in the early 60s, how would you say the mission or the challenge of AAI has changed?

We had a retreat where we really tried to look at that. And what we saw was that every decade, the organization has adjusted to kind of meet those needs. So when we look back, there are really four main pillars of the work we've been doing.

One, which I've talked about the most and which we're best known for, is liberatory education. Another is what we're calling economic sovereignty, which is helping African governments who want to chart their own course figure out where the best opportunities are to do that. Economic sovereignty is something that everybody has to some degree. The U.S. has the most because the U.S. has the dollar, right? And whatever the U.S. decides interest rates should be tends to affect the rest of the world and affect markets.

The dollar is the most used currency by far. Even enemies of the U.S. stock up on dollars because there are certain things they need dollars for. But if you think of it as a spectrum, there are some countries that need permission to do almost anything because they're very aid/loan dependent. Their economic strategy is dictated to them by the people who they owe money to. But there are always some opportunities for a government to do things independently. And we've been interested in working with governments that want to do things around education, job training, skills development, and just helping the young people understand the world better and how they fit in it.

Another area is what we're calling healing and repair. We got into this work during the pandemic when it was important for us to bring people together. Most of this work involves bringing African descendants and the diaspora together with Africans to work on issues they have amongst themselves, given their really difficult histories. There's still healing that needs to happen. And the repair part has to do with everything from acknowledging the truth of what’s happened, apologizing, and also repairing the harm, which could include reparations.

Hard things to do.

That’s right. And then the fourth area is what we call community building. And probably our biggest community building event is the Gala, which is on September 24 this year. And the Gala was started about 40 years ago as a way to contribute to a new narrative that includes real successes and real progress happening on the continent of Africa and in the African diaspora. So we tend to feature people who have accomplished things. Sometimes it's our alumni who are often coming from very humble beginnings. And sometimes it's people who have just shown leadership that's been broadly impactful on both sides of the Atlantic.

Has the event always been timed to coincide with the UN General Assembly in September? That’s when you would have access to important people, including African presidents.

Yes, that's exactly right. So we found that the messaging around the UN General Assembly, when it came to Africa, was always negative. It was famine here, war there, diseases spreading here, corruption, all these things. Many of those things are happening, not exclusively in Africa, but they're definitely happening. And yet that kind of ignores all the work that people are doing, work that's actually really brave, really good, really impactful. There are always genuine stories of progress and triumph. So we try to bring those out and to look at the potential and the progress as a theme in the Gala.

Absolutely.

Because there are going to be enough meetings about what's happening in Sudan or what's happening in DRC, that kind of thing.

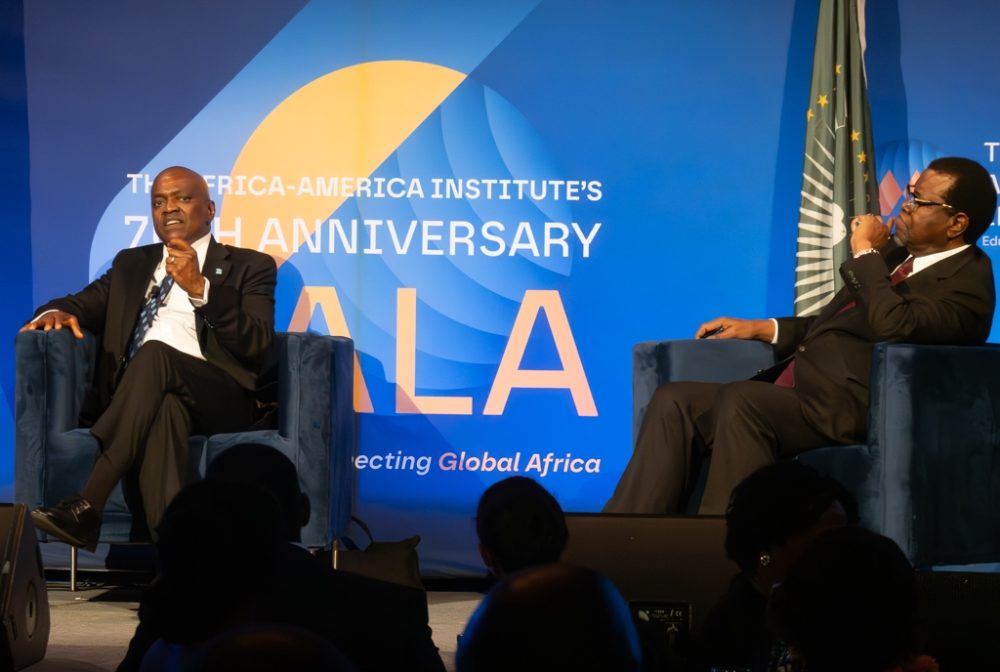

Since last year’s Gala, we lost President Geingob of Namibia, who was a speaker last year, in dialogue with President Masisi of Botswana.

That's right.

That was a big loss, and I gather he is going to be a focus, in lieu of the traditional In Memoriam presentation. Instead, there will be a tribute to President Geingob.

That's right. We’re especially proud of our association with him because he received support from AAI for two degrees and always maintained his relationship with us as he rose up, became a freedom fighter and then became the Prime Minister and then the President. And all the time he built real relationships across the continent. We have been working with his widow and the current president who is also an AAI alum and others to create an opportunity for people who knew him to come and remember him.

That's wonderful. You know, an interesting side note. I've had the honor of making music for the In Memoriam section in previous AAI Galas. Last year, I adapted a piece by the great kora player Toumani Diabaté. So just to make sure that there would be no issues with that, I called him up and told him about AAI and what I was doing. He said, that's fine. Little did I know that this would be the last time I ever spoke with him, because he died this earlier year.

Wow. When did that happen?

It happened in July. It was quite sudden as I understand. I believe the cause was kidney failure.

Okay. No, I hadn't heard that. I remember seeing him, I think, at an Afropop event in New York City. I think you invited Stephanie and I and we came to join you and he was just amazing. You couldn't believe the music that was coming from the kora.

Exactly. He was a genius, and a good friend of ours. We knew him from his early days of international recognition. So it’s a painful loss. Sean and I were in Montreal at the Nuits D’Afrique Festival when we heard the news. There were a number of kora players in the festival, and a lot of West Africans. Everyone was sort of in shock and there were spontaneous tributes. It’s still hard to believe.

Yes.

Let's talk a little bit about the future. What are the big challenges now? What are the current goals that the organization is anticipating in this ever uncertain future?

At our retreat with our board, after we reviewed our work over each decade, we started thinking about what made the most sense in order to harmonize what we do with kind of the vision that our founders had. And what we decided was we were going to update our mission statement. Now, what we say is that the African-America Institute bridges Africa and its diaspora to catalyze a more equitable and sustainable world. So in the choice of words, you can hear what we think the next phase is about. We think sustainability is something that we need to address. And fairness or equity is another thing we need to address. We think we're well positioned to play a helpful role along with many other actors in that work. So that's what we see as the next chapter.

We at Afropop have been speaking about the current situation in Africa with a lot of the musicians we've known the longest, those who are still around from the old days. We often hear statements along the lines that they feel that their generation of African leaders, by and large, have missed the mark in important ways. They’ve been too susceptible to corruption, greed and mismanagement. These veteran artists often talk about how they're putting their faith in the youth of Africa. It's up to the next generation's to right the wrongs and bring about the kind of sustainability and equity you just mentioned. What's your feeling about that when you look at the younger generations of Africans? I imagine you are dealing with students and people who have long futures ahead of them. Do you have any sense along those lines that there's some sort of generational learning going on?

I think there is generational learning. There have definitely been some bad actors. There have definitely been institutional challenges, but I think the challenges have evolved. So many of the people who, 30 years ago, were seen as the young leaders had real trouble giving up power. When they would come in, and they were the younger generation, they were saying things not much different than young people are saying today. And then they get into this system, which is very hard to make work. So I think that there are new challenges and opportunities. Thirty years ago, people talked about building industry, right? And adding value in their own economies in very traditional ways. They wanted to mine coal and do lots of dams and road projects. They wanted to build infrastructure.

If you went to Accra in 1980 and then you go to Accra today, it's been transformed in many, many ways. For a visitor, it's fun. There are so many places to go and eat, so many interesting art galleries, so many crafts. There are roads that can get you all around the country now, and very fast. There are probably 20 or 30 times the number of hotels and all these things you can do if you have money. Acra is now on the New York Times list of one of the best 50 places in the world to go.

I believe it. I’ve seen some of that change.

So the middle income group in Ghana has grown. Ghana was probably five or six million people when I was born in 1957. And it's now about 30 million people. So I don't agree that there's been no progress. I do agree that we could have done more. But I think that the world is a different place now and there are countries, many of them, that have not been in conflict for a few decades, which is one of the conditions you need. If there's a war going on, nothing good is going to happen. A place like Ghana has been very lucky. It hasn't really had conflict since the late 1970s. And while I do see the problems that remain, as I said, if you go back to the ‘60s and ‘70s, the continent has been transformed.

Without a doubt.

So I think the challenges and opportunities are linked to sustainability. Many of the things that we failed to do in terms of infrastructure, maybe now that's an opportunity. So we failed, for example, to have a lot of land telephone lines. I remember for a long time, it was all about getting phones to people, cable and all this stuff. And then cell phone technology emerged and then, and all of a sudden, boom!

Yes. It’s been a revolution.

It's one of the fastest-growing things in Africa, right? I think on sustainability, it’s a combination of having the important minerals. Africa doesn't have them exclusively, but they have more than their fair share. And also, people aren't invested in a lot of the old tech things because they couldn't afford it. So there's an opportunity to leapfrog. That's a new challenge for the younger generation. But I think ageism is always a mistake. You can't, you shouldn't, think that just age is going to be the difference because like I said, all these old people who everybody wants to get rid of now used to be young and used to be saying a lot of good things.

Okay.

I think it's all going to be around these two themes of fairness—what we call equity—and sustainability, which I think is a huge economic opportunity on the African continent. In a place like Botswana, small population, well-run, leaders who external folks judge to be really impressive. Their own populations are going to be critical, which is the nature of the beast, right? But they've managed within their limits, and I think they are poised to have a tremendous run over the next 30 years.

Those enormous diamonds they keep finding don't hurt.

That's right. Yeah. Was that the second-biggest one ever found?

That’s what I read.

And, you know, they now own more of their diamond industry than they used to. That was one of the things that President Masisi negotiated was an improved economic relationship with De Beers and a pathway to become full owners.

That's great. You know, we've done a lot of work in Tanzania in the last couple of years. And one of our guys there showed me a picture of the four living presidents, all together, you know, shaking hands and being friendly with one another. He was just so proud of that as compared with so many other countries. I've spent so much time in Zimbabwe, which is quite a different story.

Yeah, yeah. And it used to be a good story, right? And then it just changed. It just changed.

Let me ask you before we end about the arts and music. There's a big conversation going on right now about the new music of Africa, which is achieving success that we really couldn't have imagined. A lot of people who have dealt with African music back in the ‘80s and ‘90s were dreaming of huge successes, and were mostly disappointed. But now something big is happening. We did an interview the other day with a young woman from Zimbabwe. She was responding to the criticism that the new music of Africa is overly focused on cars and sex and material things. Artists are not really engaging on serious issues. And she said, yeah, but look at the fact that this is now music that African diaspora people all over the world feel connected by. And they come together. Isn't that phenomenon in itself political? It’s a big deal, and a real social advancement that these people feel so connected. It used to be that the music of each country pretty much stayed in its country. There were a few exceptions, but nothing like what we’re seeing today. I wonder if you have any reflections on the roles of musicians and artists in trying to bring about the changes that we all want to see.

Yes. I think if I had mentioned three things instead of two, this would have been the third. I think that art in all its forms, including music, is so important. It's an economic driver. I mean, that's why a lot of the music is about cars and sex, et cetera, because that's the global market. It's business, right? But as you know better than me, there's amazing work going on in music that's not popular on the radio, but is very popular live and in person and in communities. And I think for music to really have the full impact, we need to have more of the musicians owning their work.

I think right now there are large companies that have the finances to basically identify a talent, and lock that talent up by offering them more money than they ever thought they would get, right? And they do it early. And then over time, they make a tremendous fortune off that. The artists themselves also make money, but the rights are not actually owned by them, controlled by them, et cetera. Most of these things, I think, are owned by others. And as the market in Africa itself grows, I think we'll see that change happening. But I would argue this music’s impact is much broader than Africa and its diaspora. It's the whole world. I've heard people say, you know, they'll go to Germany, they'll go to Poland, they'll even go to Russia, they'll go to China. And people are singing these songs, dancing to these songs; they're going to parties; they're socializing.

Yes.

And they're learning about Africa and its diaspora in different ways. These are the culture centers. So with art, if you go to the Venice Biennale, for example, they didn't used to feature much from Africa. Now, often the buzz is around the latest thing that came from Africa or its diaspora. And I think that it promotes greater understanding. When you go and connect with an artist, a visual artist or a performing artist, I think it expands your horizons, expands how you see the world. You see the genius that can come in all forms. And you suddenly realize, boy, we all have something to offer.

It's really a remarkable time we're living in as far as that goes. You referred to the business model and how it’s changed. A lot of these younger artists build their careers with the backing of cell phone companies and clothing lines, just along the lines you described. This is a very different model compared with what was happening when we started in 1988. So it is an exciting time. And I hear what you're saying about the world. I hear this all the time too. African music is becoming the party music of the whole planet, and that's something we've all been waiting for.

Just before we go, let's just circle back to the Gala for a second. Who comes to the galas in New York? It's always an amazing crowd. I always meet interesting people there, and they seem to come from so many different directions. Who comes to an AAI Gala?

Right. That's right. It's our biggest community event. And so what you see are people from different parts of the AAI community. You see leaders of countries. You see ministers and ambassadors. These are people who we deal with in our work, and who we've built relationships of trust with. You see corporations for whom African countries are important and African-descended communities in the U.S. are important too. You see African American people from DC and people from communities around the country. All of these are part of the AAI community. You see people who are really interested in the whole world, people who have had formative experiences listening to African music, meeting Africans, eating African food, learning in Africa, learning from Africans, teaching Africans. So it's a lot of teachers, and a lot of students.

We also make sure that some of the teachers and students who wouldn't be able to afford are also represented there. The Gala is a fundraiser, after all. But it's just a really interesting mix of people from all walks of life who are coming together to celebrate.

Well, it's always an inspiring evening. We certainly are looking forward to it again this year.

I really appreciate the relationship we've had with Afropop over the years. And although both of us are getting on in time, I think we still have some more gas in the tank for a few more years. And looking forward to staying in touch and working and kind of involving the next generation in all of our mutual work.

Absolutely. We’re not done yet! Well, thanks for taking the time to speak with me. I’ll see you on September 24.

Okay, great to see you. And please say hi to Sean.