This summer, two releases from Mississippi Records have been highlights on my lengthy playlist. Mississippi Records is proudly a niche label, convinced, as stated in its recent newsletter, “Time will legitimize the good work and bury the crap,” even if the creators and distributors of said good work have long departed this mortal coil. This label is dedicated to resuscitating lost or overlooked musical treasures, including many from Africa.

Nigerian highlife bandleader Celestine Ukwu (1940-1977) and Tanzanian/Kenyan singer/guitarist John Ondolo (1917-2008) were both artist educators, inspired musicians and philosophical songwriters who thrived in the fertile early years of African independence, the ‘60s and ‘70s. For all the geography that separates them, they both represent expressions of popular African music as it was before the influences of Latin music, Congolese rumba, rock and funk transformed genres continent-wide. Whether or not these artists will be listened to a century hence, as the label newsletter predicts, is anyone’s guess. But they sure sound sweet in 2022.

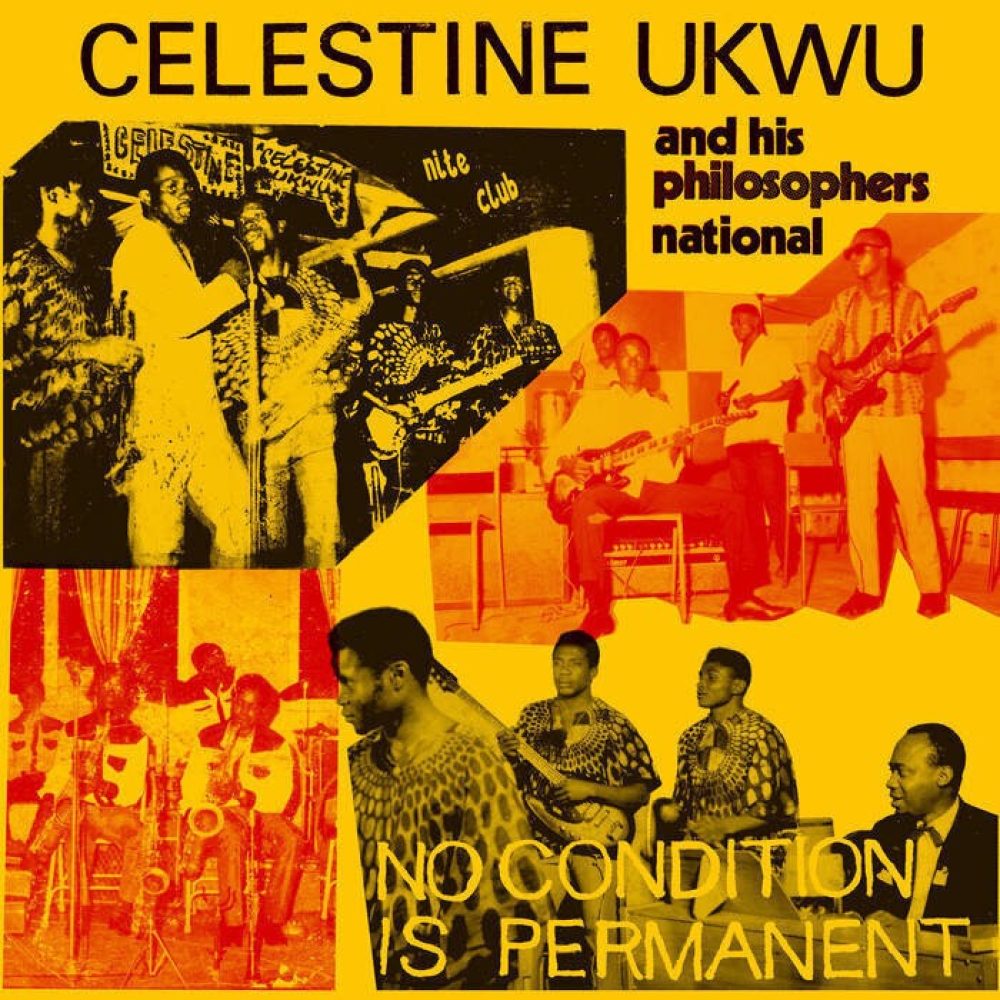

Celestine Stanley Onwurah Ukwu, with his band The Music Royals, breathed new life into Nigerian highlife in the mid-1960s, a time when the genre was beginning to decline in the face of stiff competition from emerging styles. A teacher by profession, Ukwu had an advantage in that he had toured the Republic of Congo and had learned enough about the rising Congo music wave to infuse his highlife with a little extra pep, notably in the pumping, muscular bass lines.

But by then, Nigerian highlife was about to be devastated by one of Africa’s most horrifying 20th century conflicts, the Biafra War (Nigerian Civil War), which claimed an estimated two-million lives. In 1967, when the Eastern Region declared independence as the Republic of Biafra, Ukwu was recruited to sing for the new nation. His composition “Hail Biafra,” also recorded by the then “king of highlife” Cardinal Rex Jim Lawson, amounted to fighting words in the eyes of the Nigerian government, which determined to crush this separatist rebellion by any means necessary. (For more on Lawson and the Biafra War, check out Hip Deep in the Niger Delta.) As the war surged, Ukwu’s record company was bombed in a Nigerian air raid. Ukwu stuck to his guns in defending Biafra, but his band scattered to the relative safety of Lagos, as did most highlife musicians from the Eastern Region.

Ukwu’s renamed The Music Royals as The Philosophers National, and the tracks on this release, No Condition Is Permanent, are selected from three of that band’s post-war, 1970s albums. The band became a school for highlife musicians in the '70s. Although the genre was then being overshadowed by Yoruba juju music, Afro-funk and Afrobeat, it had lost none of its polish and charm, and none of that has faded with time.

On “Onwunwa” we hear a profound melancholy in Ukwu’s vocal, even as the band percolates with rapid percussion, bubbly muted guitar, and mournful horn lines. This is essentially joyous dance music, but the specter of death looms throughout the lyrics, which focus on impermanence, faith and the need to rise above petty gossip, boasting and jealousy. The selection wraps up with a mesmerizing, nine-plus-minute instrumental that says it all: “Tomorrow Is So Uncertain.” The track is a lilting 12/8 groove showcasing tight arranging, bell percussion, that pumping bass, chiming guitars and breezy brass interludes. In all, this album is a fine addition to the growing catalog of vintage Nigerian reissues.

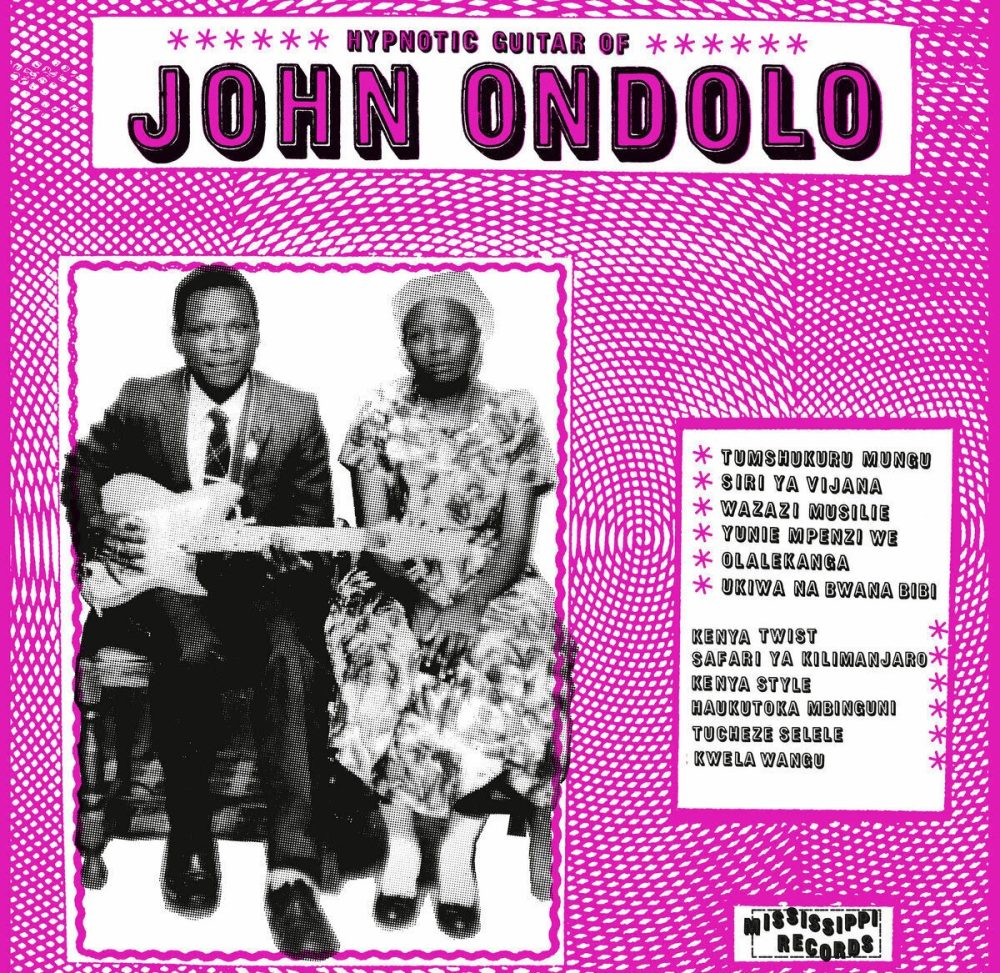

Moving to East Africa, we encounter The Hypnotic Guitar of John Ondolo, a set of 12 brisk tracks mostly from the 1960s. John Ondolo Chacha happens to have been born and died in the exact same years as my father, although my dad did not die during a church service leaving two wives and 11 children behind. But I digress. These recordings sample Ondolo’s unique open-tuning guitar style, featuring cycling two-chord finger-style vamps often with a drone in the bass—hence the aptly noted “hypnotic” effect. Most of the tracks are performed on acoustic guitar with minimal percussion—often a Fanta bottle—flute and a second singer adding close male harmonies. Ondolo went electric in the ‘70s and became a founding member of the legendary muziki wa dansi juggernaut: Vijana Jazz Band.

Although born in Tanzania, Ondolo spent most of his youth in Kenya, at a time when Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya were effectively one big British colony. He showed musical talent at Catholic school, but didn’t stay long as it was too expensive for his parents. After that, the guitarist was self-taught all the way, and he used guitar to evoke folkloric sounds, sukuti drums, zeze fiddle and the nyatiti lyre. Ondolo enrolled in the British Colonial Army from 1942-47, and began recording only in 1959 for the South African Gallotone label.

In 1962, he returned to Tanzania for the first time since childhood, but continued to spend time in Kenya where there was a recording industry of sorts. In Tanzania, music was recorded only at the state radio station. Ondolo worked a number of jobs and wound up working in the film industry, producing, composing and touring Tanzania with a mobile cinema truck screening educational and propaganda films in villages when he wasn’t performing with Vijana Jazz. In the 1980s, he lost his left hand in a car accident ending his music career.

But these recordings predate all of that. The sound scape is spare, Ondolo’s vocal clear and plaintive, his guitar picking seductively along in a narrow harmonic range. The rhythms are forthright, with scarcely a hint of the Cuban clave lilt that would soon define so much African popular music. “Kenya Twist” plays more as a drone-fueled walking song than an actual twist. “Safari Ya Kilimanjaro” showcases a flute and warmly harmonized vocals celebrating the wonders of the Tanzanian wilderness. As with Celestine Ukwu, the songs are often morality tales, guiding listeners to trust God and beware the devil who “prowls around you like a lion.” There is marital advice and in “Siri ya Vijana (Secrets of the Youth)” a harrowing story about a girl who dumps her baby in a ditch and turns to prostitution. “There’s the traitor/Beat her. There’s the traitor/Jail her,” goes the refrain.

If you visit Mississippi Records to sample these delights for yourself, don’t miss the Kiko Kids Jazz’s Tanganyika Na Uhuru, another gem from 1960s Tanzania, released by this label in 2021.

Related Audio Programs