Born into the Cissokho family of griots (some relatives spell it Sissoko or Cissoko), it would have been a challenge for Momi Maiga to imagine himself becoming a dentist or, really, anything other than a musician growing up. Maiga received his first kora, made for him by his uncle, at the age of six. Though as a kid, he gravitated towards playing percussion, but at 18 years old, Maiga found himself in Sweden collaborating with musician Ale Möller on one his projects integrating world music with Swedish trad folk. In 2018, Maiga made his first trip to Barcelona to collaborate with a local musician through the Barcelona Music Museum. It was there he first heard the music of the legendary flamenco musician Paco de Lucia and it became his goal to fuse traditional kora with flamenco.

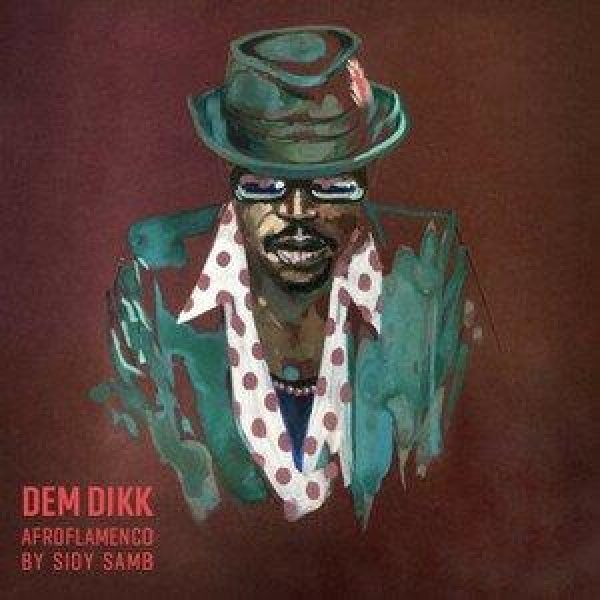

Of course, Maiga isn't the first kora musician to look for ways the kora can work with other musical genres, including Flamenco. In fact, Maiga's cousin, Seckou Keita, has had great success with Cuban pianist Omar Sosa. The African link to flamenco was also explored in our program The Hidden Blackness of Flamenco, back in 2018. And we can’t forget Toumani Diabate’s groundbreaking Songhai albums with the band Ketama back the 1990s, or Sidi Samb’s powerhouse Seville-based band Afroflamenco. The kora’s global travels was also the subject of our Journeys with the Kora program in 2023. Clearly, this is fertile ground.

Maiga released his debut album, Nio, in 2022, wherein he started to explore this fusion. And to make his sound even more original, he performs accompanied by a cellist, a violinist and a percussionist. One album track featured Goya awarded Catalan singer Sílvia Pérez Cruz, while another featured the voice of his cousin Seckou.

Having since settled and started raising a family in Catalonia, Maiga's sophmore release, Kairo, came out last year and took a Catalan critic's award for “best non-Catalan language album.” Maiga sings in both Mandinka and Wolof. And success and notoriety continues to come his way as Maiga was invited by fellow Catalan resident and album co-produer/musician Michael League (Snarky Puppy, Bokanté) to record on Youssou N'Dour's newly album, Éclairer le Monde – Light The World. While performing with N'Dour last month in Paris, N'Dour hailed Maiga as an “ambassador of a new generation of kora.”

We were thrilled to see Maiga perform at this year's Jazzahead conference in Bremen, Germany last month. He delivered an exciting and transcendent set, and we were equally thrilled to have a chance to sit and talk with him the next day. The following interview was edited for clarity and length.

Ron Deutsch: Were you listening to Spanish music before? Was it something that you aware of, or was it something you discovered when you first came to visit Spain?

Momi Maiga: I discovered when I came. Yeah, I didn't know flamenco. Yeah, in Senegal, I have never listened to the flamenco. I came to Spain and I was with good friends and musicians and they showed me what is flamenco. They showed me Paco de Lucia and I was like “Wow what is this? I want to do something like this.”

Listening to you last night, I was completely blown away because you made the kora sound like a flamenco guitar,. And then there were other times I felt like it sounded like an oud.

I already knew the sound of the oud and the sound of North Africa. And in Spain, you know, they also have these Mediterranean sounds that sometimes can look like North Africa because they are very close and have some kind of cultural influence.

When you went back home after discovering this sound, and the Cissokho family is all there and you're like hey, “There's this flamenco thing I'm digging.” Were they like “What are you doing?”

I didn't get this kind of feedback. I think they kind of liked it. “He's doing a fusion with our culture.” But I'm sure that some traditional people in Senegal or West Africa, maybe they are a little bit like, “I don't know what are you doing. You are throwing out our traditions.” But yeah, my family, they were all good, because I saw this before, this fusion, with Indian people, with Swedish, and English musicians. But you have to learn the tradition first.

So how did you go about figuring out to play flamenco? The tuning, melodies, how the music all comes together?

Listening. A lot of listening. Because, you know, I cannot read music. Our tradition is oral. So, listening a lot and playing with a friend who played good flamenco.

So, from the time that you heard Paco de Lucia to the time you felt like you could start writing music in this fusion style, how long did that take?

I have been living in Spain now five years. So I don't know, maybe in two years it started to make sense. I released my first album two years ago. So yeah, I made a mix of the bulería and a traditional song called “Mansani Cissé.” “Mansani Cissé” is an important song in the kora repertoire. I tried this fusion with bulería, and it was very, very, very good.

Two years? That's pretty incredible. And it seems in Spain, they've also been very welcoming of this fusion.

Yeah, yeah. I didn't get any bad commentary. Because of this song, “Mansani,” I won an award, you know, the Alícia Award. It's an award in Catalonia. So this was a good signal, you know? They are happy about that and I'm very glad and very thankful. It's not easy, flamenco people are really very, you know....

Particular? More or less so than the kora people?

I think maybe they are also maybe 50-50. The most traditional people in my country, maybe they will not accept this. And the more traditional flamenco people, maybe they are not happy a lot. But I didn't feel any bad vibes or commentary.

You live in Girona, I live in Barcelona, and every day I see Senegalese immigrants struggling to get by. And I'd note Spain, at least, is one of the few countries that is still welcoming immigrants. Are you in contact with the Senegalese community in Catalonia?

I don't have contact with people who are living in the streets, but yeah, I have some Senegalese friends who are living in Barcelona working with good jobs. But I have seen these people in this tough situation and it's not that they don't want to work. They want to work. They came here to make their life better and help their family. The problem is the papers thing, getting the permits to work. My situation was complicated also to have the papers. I'm lucky that I have a Spanish girlfriend who helped me. But still, it's horrible, you know? It's not easy, and it's getting worse and worse. They are in this kind of situation. Going in circles.

I speak to these things in my concerts. I didn't have the chance to play “Ocean” last night. “Ocean” is a song that I dedicate to these people who are coming here for a good life, a better life, and the people who died in the sea, searching for this struggle. I always talk about these people. I always tell people to think about the fact that they are people too. I say that I'm here playing and you are enjoying my music, you know, but there are people who look like me and are suffering. They are persons, just as you and me. So I always try to remember them. Because, you know, sometimes it looks like we are just numbers. They say 100 people died or 200 people died today in the boats. I don't know why, but I have this feeling that we are numbers. And they don't know why we make this trip, because to have a visa is complicated.

Before I moved to Spain, I was invited by the Museum of Barcelona to perform, and even two days before I didn't know if I had gotten the visa or not. And the director of the Museum called the Ambassador of Spain in Dakar to ask what was happening. So you see the complexity of having a visa. It's like we don't want you here. But they [the Spaniards] can come to Senegal whenever they want. We don't have this. Why? Why is it so complicated? So this is the thing I try to explain. Because we are poor people. But they get all the minerals, you know? The minerals are welcome, but the people, no. We need to have a good deal, a win-win, because they exploit the exploitation.

Your first album, Nio, can be translated to mean “soul” in Mandinka I read, but it actually means more than that, yes?

Yeah, yeah, it's not like soul in just that way, but it's all about things that have souls this planet. It's also about the humanity, also about education. I also talk about love, you know, because it's all around the soul. The responsibility of the soul. You don't just have a soul, you have it for a reason.

And the second album Kairo, means “peace.”

In Mandinka, yes. I choose this name because as a griot we have the responsibility to bring people together. And whatever we sing, whatever we play, it has to serve the population. This is our role in society. Going back to the ancient empire. I was born as a djeli (Mandinka for griot), so it's important to me. Everything, every music that we do, is to serve the population. And the Kairo album, I was doing this album in a time – and still – we are in the time of war. So as I was saying, I have to try to say to the people to be together, because this is my role. This is what I can give here in this war, you know, as a djeli. So that's why I chose this name.

I'd like to ask you to pick a song from either album you think best represents this notion of trying to make people understand the responsibility of the soul and trying to bring people together?

I think “Mbolo” on Kairo does that. First, it means “union,” to be together. So I think it's the best song to represent this “let's be together” idea. In the sound you can hear it. There aren't many lyrics, but you can deeply feel this thing, to be together in respect and peace. I think about these things when I compose and keep that in my feeling.

Tell me about connecting with Michael League and Youssou n'Dour.

Our first contact with Michael League was to produce one song. I had a big band, like eight people, and we wanted him to produce one song because I had heard about him and he was also living here in Spain in Catalonia. And I love that Snarky Puppy. So my girlfriend contacted him to produce one song, but he said that he'd prefer to produce an album. But this band was before Nio, and we weren't doing an album, just one song. Michael has a studio and so we used it to record this one song.

But then later, we were playing with [Catalan pianist] Marco Mezquida and he invited Michael, and we met there. And we got to know each other. So then he is going to do production for the Youssou N'Dour album and Michael called me “Momi? Are you interested to play some kora on Youssou's new album?” And I'm like, “What....?! Are you talking about the Youssou n'Dour I know from Senegal?” Then I say, “Wow, bro! Yeah, of course. I would drop everything I'm doing and go. I'm coming.” So I went and it was amazing. And then he asked that I do some backing vocals. And so I go to Michael and say, “No, I can't do it. I can play kora, but I can't sing here, because he is having the best singers in Senegal doing some backing vocals. This is too much for me.” And Michael is, “Momi, come on.” So okay, I said, “I'll do it.” And I did, and it's great, great, amazing.

I see you have to go. Thank you and continued good fortune.

Thank you.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles