By Ron Deutsch

Banner image: (c) Frédérique Ménard-Aubin

Having covered both the Montreal International Jazz Festival and Montreal's Nuits d'Afrique Festival for over a decade, we can say it's very rare for an artist to play at both festivals in the same year. Especially when it comes to filling a slot for a local world music artist, there are so many to choose from in the city. So when we saw that Naxx Bitota, an artist new to us, was booked this year at both, we guessed there was something special about her. And we guessed correctly.

Bitota was born in the Kasai region of the Democratic Republic of Congo, spent her teenage years living in Belgium with relatives, then reunited with her parents in Quebec in 2008. From the age of nine, she knew she wanted to be a singer. So she studied gospel, classical and folklore music, singing with various choirs. But it wasn't until 2018, when she began to take the stage with an original project she calls “Afropop Mutuashi.” But then, as for many musicians at that time, the pandemic put a stop to performing live. So Bitota, accompanied by her husband, Lionel Katshingu, recorded and released their first album, Kuetu (which means "Home" in Tshiluba, the local language from the Kasai region). And one of the songs from that album, “Maamu,” found its way onto a Putamayo compilation in 2023.

What Bitota calls “Afropop Mutuashi” is a blend of Congolese rumba, reggae, mutuashi, Afropop, and lively soukous seben rhythms. On stage, Bitota sings and dances, supported by four other dancers. When specifically dancing the mutuashi, she ties on a scarf around the waist to visually accentuate the movement, which is a typical accessory of the genre. Lionel conducts the band, while playing the bass guitar.

Mutuashi is both a musical genre and a dance style. It originated in Kasai, and some say the word was shouted to encourage dancers, but then became synonymous with the particular dance they were doing. The artist most associated with mutuashi is Tshala Muana, known as “the Queen of Mutuashi,” who passed away in 2022. The dance is said to have begun as part of a fertility dance, but out of that context it was considered by some to be scandalous, to the point were Muana's concerts were banned in places because her performance was considered to be “overly suggestive.” Recently, mutuashi has become a viral phenomenon on social media. Here's a typical video you can find searching “mutuashi.”

One more note. Seben is a musical term describing the fast, guitar- and animation-driven final section of a typical soukous song. That’s when the dancing goes into overdrive. According to Wikipedia, the “origin is a subject of contentious debate.” The leading theory is that it refers to the 7th chord that adds tension to the music, but the real mark of seben is pounding rhythm, a beat that has birthed many specific dances over the years, some of which have naturally found their way as TikTok dance challenges.

We found some time to sit down with both Naxx and Lionel between the festivals. They are a delightful couple and we thoroughly enjoyed our conversation, which has been edited here for clarity and length.

Ron Deutsch: So I guess my first question is, do you think the frites are better here in Montreal or in Belgium?

Naxx Bitota: [LAUGING] I think for the frites, Belgium and for the waffles also... and maybe for the chocolate also.

I read how when you were very young you had already set your sights on becoming a professional singer.

Naxx: Yes. Because I come from a family that likes to sing. They like to sing a lot. So it's like an obligation to sing.

Were you singing professionally then or just for fun all the time?

Naxx: No, no, no, no. Just for fun. I developed this love for singing and I was thinking to make that a professional career. All my brothers and my sisters, we all sing, but I'm the only one who made it a profession. My parents were not surprised about this because I was talking about it since I was a kid. I knew I would travel around the world and would sing around the world. But they gave me one condition: You have to finish university and then you can make your music the way you want.

So when I was a kid I spent my time in the choir doing classical music, opera. I also did theater, but not my own thing. When I was wondering what kind of rhythm I'm going to use for my career, for me, it was mutuashi. The rhythm, it just speaks to me.

What was it about mutuashi that attracted you? And please talk about Tshala Muana. the “Queen of Mutuashi.” You did a tribute show to her at one point.

Naxx: So yes, I was interested in her since I was a kid because she's like a local hero. And yes, I did a tribute to Tshala Muana when she died in 2022. She was the one who made mutuashi popular and brought it to the world. Now first of all, mutuashi is a kind of dance and of singing. And being originally from Kasai, as Tshala Muana was, I'm only trying to do my part. It's a very special, traditional music that comes only from Kasai.

Did you ever get to see her?

Naxx: Of course. When we were kids, my mother was listening to Tshala Muana. And I was liking her music and dreaming to be like her. But I only saw her one time, and it was so fast, because I was so young. And my family told me that I could not stay to see the whole show, but they let me see, like, three minutes of seeing her dancing on stage.

She got into a lot of trouble dancing mutuashi at the time, yes? It was considered a little bit maybe too sexual for the public at the time.

Naxx: The dance especially; you move with the waist. When you see the dance it's a little bit sexual – and some artists can transform that – but it's still a traditional dance, because it means we are hoping for fertility. So some people could see it as a sexual dance, but it's not. We have to continue to multiply people for our culture not to die. So it's not sexual, though some people can use it in that way. But for me it's still very traditional.

You tie some kind of scarf around your waist...

Naxx: Yes, it's a kind of fabric with African prints on it that we put around the waist.

But you're not wearing it all the time. It's there on the stage and then you pick it up when you're going to do the dance.

Naxx: Yes, only for that. Because on stage, sometimes I also do like a Congolese rumba dance, so I don't need it for that kind of music. But for mutuashi, I need to have it. Because it's the way. I have to respect the traditional way... And also, I like it!

I put some reggae in the mix also, because, I call my music “a new mutuashi.” It's a modern mutuashi, so I can make a crossover with reggae. If you listen to the new album, you have the song “'64.” It's very classic mutuashi. And near the end of the album, you also have “Mukalenga Mukaji,” and that's a fusion of reggae and Mutuashi.

One thing that's very interesting to me – and you've spoken about this – is that when one sees you live on stage, you feel the music is the background to the dancing. But when listening to your album, there is no visual, so the focus is on the music. So, as you've said like, the album is about ears, and on stage it's about eyes.

Naxx: You know there's this thing – bi-polar – and I am that person. [LAUGHS] With all my songs, I can play in a theater where people are sitting and just listening. And I can also play like you saw at the Jazz Festival, to make people dance. For the same song, I have a version where I can be so quiet, so smooth, you can close your eyes and just listen to the music. But also the same song, you can have at festivals where you can't close your eyes. You have to move. I think just like my personality, the same song can be groovy or peaceful. It's all depending on how I feel and also the audience. So when I am in a quiet theater, I'm a quiet girl. And when I am in a festival and people are getting crazy, I'm going to be crazy also.

Lionel, you're also involved in this, you play bass and are also the musical arranger. Do you also compose some of the songs?

Lionel Katshingu: I arrange and compose all the music, but all the lyrics are Naxx's.

How do you navigate Naxx's quiet versus crazy sides when creating the music then?

Lionel: She said it very, very well. But for me it's not really that on stage I want to move the people, I want the people to be moved by something. It can be like for the dancing, but it can also be moved through the feelings. So it depends on the venue, as she said. It depends on how we feel, but also what we want people in front of us to feel. So that's why we have so many styles of playing the same songs, because those same songs have a thematic that can get you angry or get you sad or even give you ideas to be a better person, you know? So that's how we juggle around it.

And when you guys create together, do you write the music first and then Naxx writes lyrics, or does Naxx comes with lyrics then gives it to you? How do you guys work together?

Naxx: I think I come and tell Lionel I want this kind of music, all my crazy moods for this and that. And then he's going make music. So yeah, it's a nice partnership.

Lionel: Exactly. Like '64, it's her album. '64 is herself. So she explains that she wants a song with a rhythm of this region of Congo, and that she wants to express this kind of emotion. And just with that, I can create something. And when she's ready to have the lyrics, she puts them on the music, and if there's something that she wants to say or needs the music to move a certain way, we work together to have the music really be in place with the singing.

And the lyrics are all in Lingala?

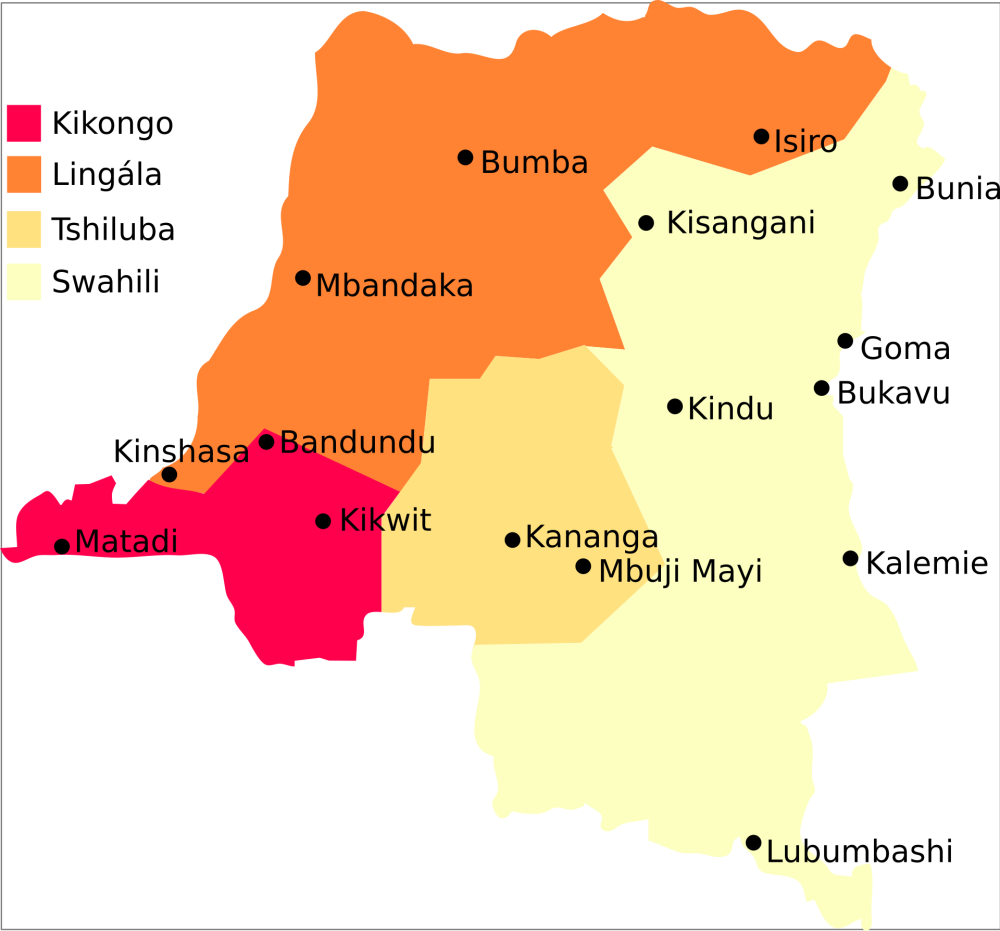

I sing Lingala, in Tshiluba – which is the language from Kasai. Also, Swahili, a little bit of Kikongo, and some French and English also.

Talk to me about the seben. Can you explain to me what that is?

Lionel: The origin of the name is unsure. But what we understand is that some Congolese people were playing with some people that were speaking English and they were saying “go to the 7th,” but the Congolese understood “seben.” This is since the ‘60s.

It's not at all linked with the seventh chord actually, it's really just a name that has been coined and stayed throughout the years. But what we call seben is actually a kind of galloping rhythm within a rumba for dancing. But it has become a style of its own. So it was just kind of like rumba first, but then it began to take up a lot more space and there's been songs only doing the seben.

And what is the significance of this number 64. It's the name of the album and a song on the album.

Naxx: [LAUGHS] Okay, so it's my name. So, yes, my name is Bituta Mulumba. And when we were young, my brother gave me the nickname “Naxx.” It just comes from because I was given another name that I don't like which was Alexandra. I call it my slave name. I don't like it because it doesn't represent myself. But then my friends from school gave me the nickname “64” because I was the first one who had a Nintendo 64. So then they all called me “Naxx 64.”

Do you still have a Nintendo 64?

Naxx: Yes! I have it. I love GoldenEye and Mario Kart. They both take the first place and then Mortal Kombat is second.

But the song "'64" is not about Nintendo.

Naxx: [LAUGHS] No, it's not about Nintendo... but it's about the real me. Yes, me and all my emotions. When I am strong and when I am weak, it's talking about that. But no, the Nintendo people didn't pay me for that.

Can you also pick a song that you feel really represents some sort of message you want to communicate to audiences?

Naxx: I think it is the second song on '64 – “Poto Pota.” I want the youth of Africa to hear that song, to understand that to go in America, Europe, is not paradise. They still think that when you come here you will be happy right away – they're gonna give you a house, a car, you're gonna have a job – but no, no, no. You have first to fight to have a document. And after that, you have a lot of other problems also coming. So maybe you're better to stay where you are and see your potential there, to see what you can do there and be better at that. And then you can travel around the world. Because then you will have something. You will realize something. So “Pota Pota,” for me, is the song that I want the youth of Africa and everywhere to be heard.

That's a running theme with several artists that I've spoken to, that they really want to promote people staying in Africa and build it up, but it seems to be a struggle because things are difficult there, as well. People always think the grass is always greener somewhere else.

Naxx: You see? The media continues to sell that it's a paradise here. “You have to come here, you will be better here. There is nothing to do in Africa. It's always poor.” But no, I want for the youth to understand that there are opportunities there and they can do something.

But why do you think the media does that? Is it the African media or the western media that says that?

For me, I think all the media is selling that here is better than in Africa. We know that it's better at some point, but I think also we can encourage them to be there, to take responsibility to do something there. A lot of people come here after college, and they are like taxi drivers. and they are not happy. So you can be what you study for in your country, and you can be someone.

But when I came here. It was not my choice. It was my family. And now I don't have any family in my country, but I want to go back there because I feel I can do something.

I guess my last question is that you have this group of dancers that comes on stage with you during the show. Now Lionel, you are in the back just standing there with the bass. Do you get jealous of these men surrounding her on stage?

Lionel: I don't worry about that. I'm good because there's two male dancers and two female dancers. So if I'm worrying, she's worrying also. So everything is balanced. I've gotten used to thousands of people looking at my wife... so no problems. [LAUGHS]

Naxx: [LAUGHS] That's my husband.

At the Nuits D’Afrique, Afropop’s Banning Eyre also spoke with Naxx and Lionel. Banning had not been in town either of her festival shows, but he did listen to the album, ’64, which was produced by Lionel. Here’s a little of Banning’s conversation with Naxx and Lionel about the album.

Banning Eyre: Tell me about the song “Kamulangu.”

“Kamulangu” is a song of unity. It was created by the Baluba while they were building the railroad. It’s historical and folkliric. They sang this to come together, to show unity and build the rails that would connect the country. Of course, today the rails don't exist anymore. But this is a song that calls for all Congolese to be together. Because with everything that the Congo is going through, there are many divisions and there are even ethnic groups that are dividing themselves. And so I said to myself, “I'm going to make this song with the four official languages of Congo: Tshiluba, Lingala, Swahili, Kikongo.” It’s to say to all Congolese, “We must come together; we must not divide ourselves.” This is very important because at the moment, we see everything the Congo is going through with the mines and minerals, with the war in the East. This is what “Kamulangu” is about.

You wrote this song?

I wrote this song with my mother.

Lionel: I would add that since it's a unity song about getting the people together, in “Kamulangu,” you hear the environment. There are birds in it. And I chose birds from different continents to be in it so it could express unity through also sounds. And I could ask a question to every listener. Can you identify the birds?

You know, there’s an app for that.

Naxx: There’s one special bird in there. We’ll leave it a secret.

Okay. Let me ask you about the song “Mukalenga Mukaji.” I can really feel the mutuashi in that one.

“Mukalenga Mukaji” means “queen.” In Tshiluba, it's longer: Queen Mukalenga Mukaji. In my lineage, we have royal blood. I have duties to fulfill in my royal lineage, but I cannot do those things because I am not a Mbuji Mayi. I've never seen a Mbuji Mayi. You have to go through a whole initiation for that. So in the family we arranged for my cousin to take that role, because my sister and I cannot. I am here; my sister is in France and she has the same situation as me, more or less. So in “Mukalenga Mukaji,” I'm saying that I'm still holding my place in the lineage, but from a distance, as an artist. If I can't be on the royal chair, I'm still going to be in front of a microphone to talk about my culture. It's time for me now to take my culture and my work in hand and heal people, especially women.

Lionel: This is a very special song. Naxx heals people with her music. When you see the show, you can see how she heals people. My great grandfather was also a traditional chief and we chose to put this album together to continue the traditions of our ancestors. In that song, there's a real traditional way of playing the guitar, but there's also a reggae feel in it. We've been traveling and meeting a lot of different cultures, but we keep our roots. We add colors from every other culture that we respect and appreciate, and that has brought a lot to us musically and spiritually.

Naxx: The opening song, “’64,” is slow. I am talking about my feelings there, talking about my joys, and especially of my pains, my perception of the world. I decide to let go [of my home] and just leave, but with many pains. I accept the decisions of my family, my friends and this world. I accept that.

Lionel: Also, for that song “’64,” since she has a a strong classical music background and I also learned music by playing trombone in an orchestra, I wanted the song to touch that particular part of our musical adventure. That's why I put cello in that song, and contrabass. It's not what people expect. It's just by surprise.

I was talking with the Haitian musician Wesley yesterday, and maybe this is a bit similar for you. He is settled here. He has this great band and a great career going, but things back in Haiti are really, really tough. Maybe it’s similar for you with Congo. There’s a funny paradox. Sometimes countries that have the hardest histories create the happiest music.

Naxx: I've often been told that. “Your country is in trouble, but you're one who brings joy to the world.” That's it; that's life.

Lionel: There is one special song at the album, “Furah Yetu, which speaks about that. Maybe you can explain a little bit the lyrics.

Naxx: In that song, I say it's not time to rejoice now, because the world is going very, very wrong. There are people who continue to die; there are more and more atrocities in the world; there are people who lack even a glass of drinking water. There are people who are starving; it has become a daily occurrence. So we don't have to rejoice.

Hmm. Well, as you know, the music audiences in Kinshasa and Brazzaville know what they want. They are quite particular, and the mainstream public wants rumba, soukous, ndombolo—that whole family of styles. But recently, one of our producers went to Congo and did a report on the alternative music scene in Kinshasa, groups like Jupiter and Okwess. They're doing very modern electric music, but not soukous, not even mutuashi. I was also speaking with to Les Maman du Congo here at the festival. What they're doing is completely off the map, not following any established path. I think that some artists, both there and particularly abroad, like here, have the freedom not to worry about audience demand. Although I should note that you do have two hot seben jams on this album.

Yes. [laughs]

But talk about that. What's your relationship to the mainstream rumba/ndombolo sound?

Yes, it's true, there are a lot of people who say, “Ah, but you're Congolese, you have to do rumba, rumba, rumba.” And I love rumba. We have “Ya Nini.” That’s a rumba song. But at the same time, I want to do what represents me. I want to be original, to really be who I am and not just please people. I will always do rumba, that's for sure. But I'm not going to be responding to the population's demand to do it.

I think being in this environment helps. Montreal is very supportive of innovation, and experimentation, isn’t it?

Yes. They are very open, very ready to listen.

So let's talk about your live band. Describe it.

Well, the band is composed of people who come from different places around the world, but they are professional musicians who are willing to understand our culture, learn it and play it the way it's supposed to be played. They are open and curious.

Lionel: We have an American musician who is fluent in Congolese language, but he also brings a new language, because he's not from Congo. He can try forever, but he will never play exactly like a Congolese.

Is this a guitarist?

This is a guitarist, and this is what I want. I don't want him to play like any other person. I want him to have his own signature sound that leads our group into something unique, you know? We also have a few drummers we play with. There's [Lionel] Kizaba who played on the album. He's Congolese also, and he is a driving force in the rhythm section and we appreciate him very much. But we also play with the Cuban and Guadalupian drummers, and Cameroonian drummers who really understand the importance of Baluba tribe and culture. And there's me on the bass. This is a usually how we tour, but we can also add percussion, and two other guitarists. Usually, Congolese music is played with three guitars. So we can add those, and we can add backup singers and also dancers and choreographers that are with us when we do theatre stuff.

You have a big Congolese community here in Montreal, don’t you?

Ah well, yes. The Congolese community is very present, and very joyful I think. Very curious too. In fact, the Congolese community comes together a lot through spirituality. There are religious communities, and, I could say, political ones. There are now a lot of Congolese who are getting involved in politics and it's growing at that level. So there are people like Pierre Kwenders and Kizaba who are also opening up with their art. The community is really establishing itself in terms of organization.

How many Congolese are there in Montreal now?

I can’t say. I’d have to look it up. But we are the second largest community after Haiti.

Well, congratulations on the album. It’s really unique.

Lionel: I would like to say that I've seen how Naxx worked on this album. I was there for every session, and her whole heart, her whole soul, is inside it. So if you're into spiritual feelings, listen to how she sings. Even if you don't understand the words, you will understand the message.

Beautiful. Thank you.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles