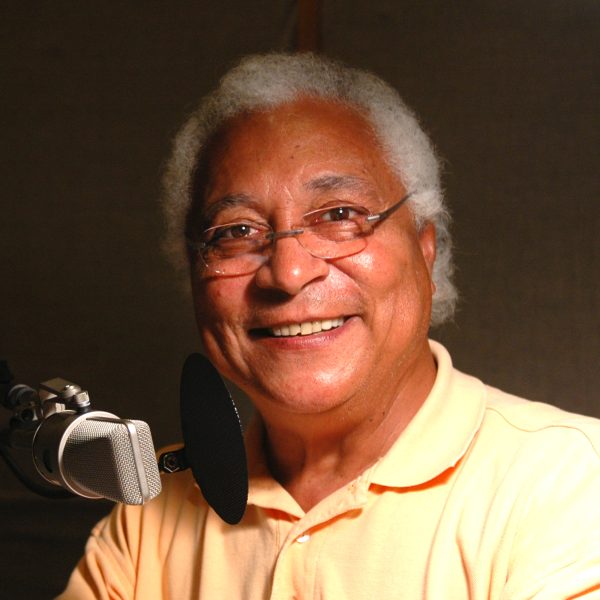

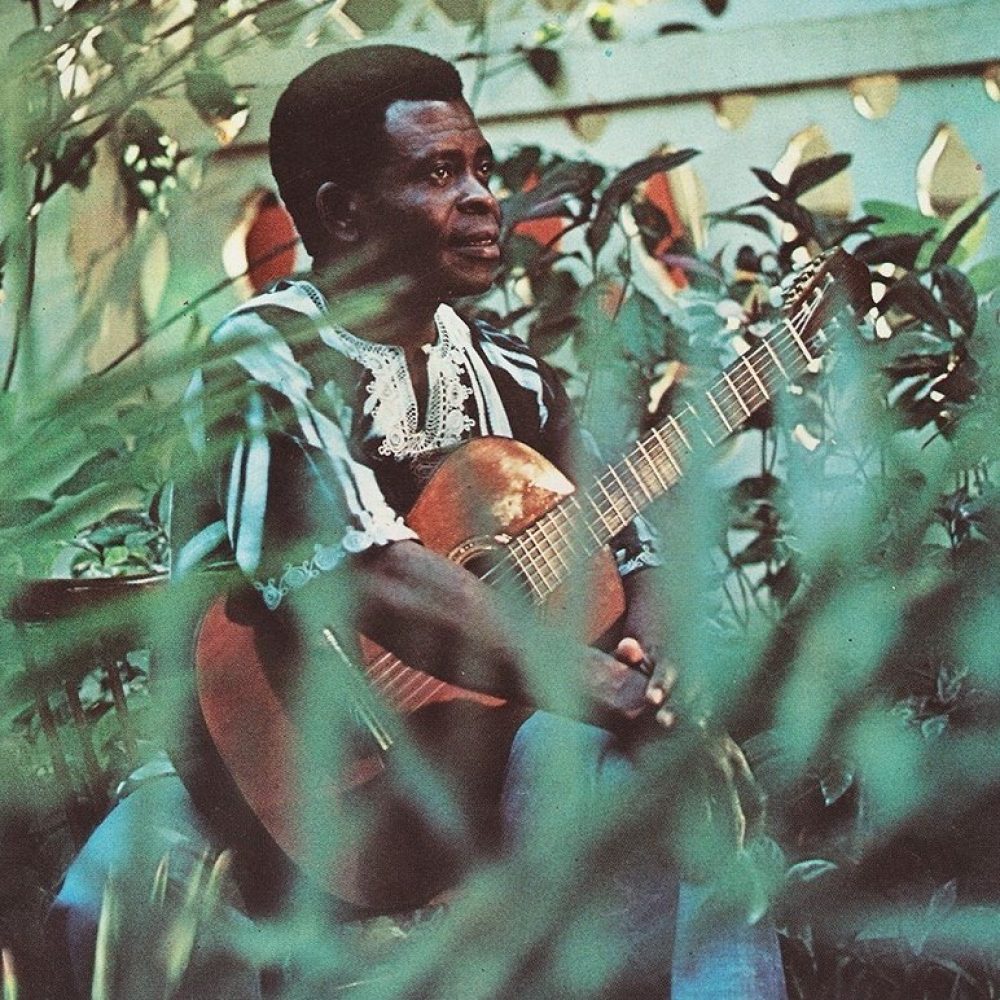

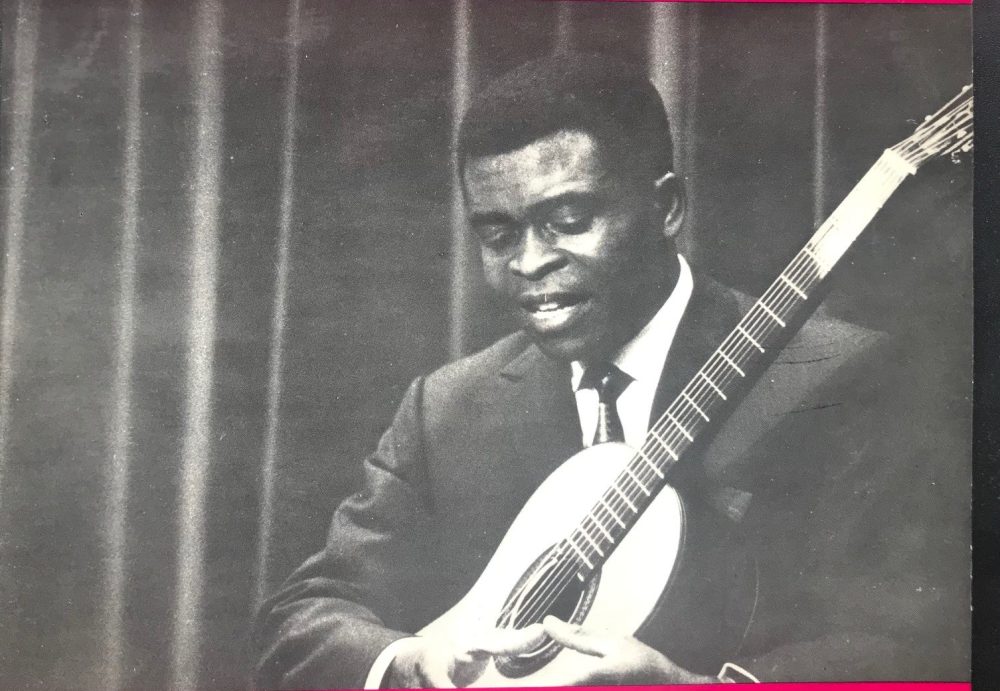

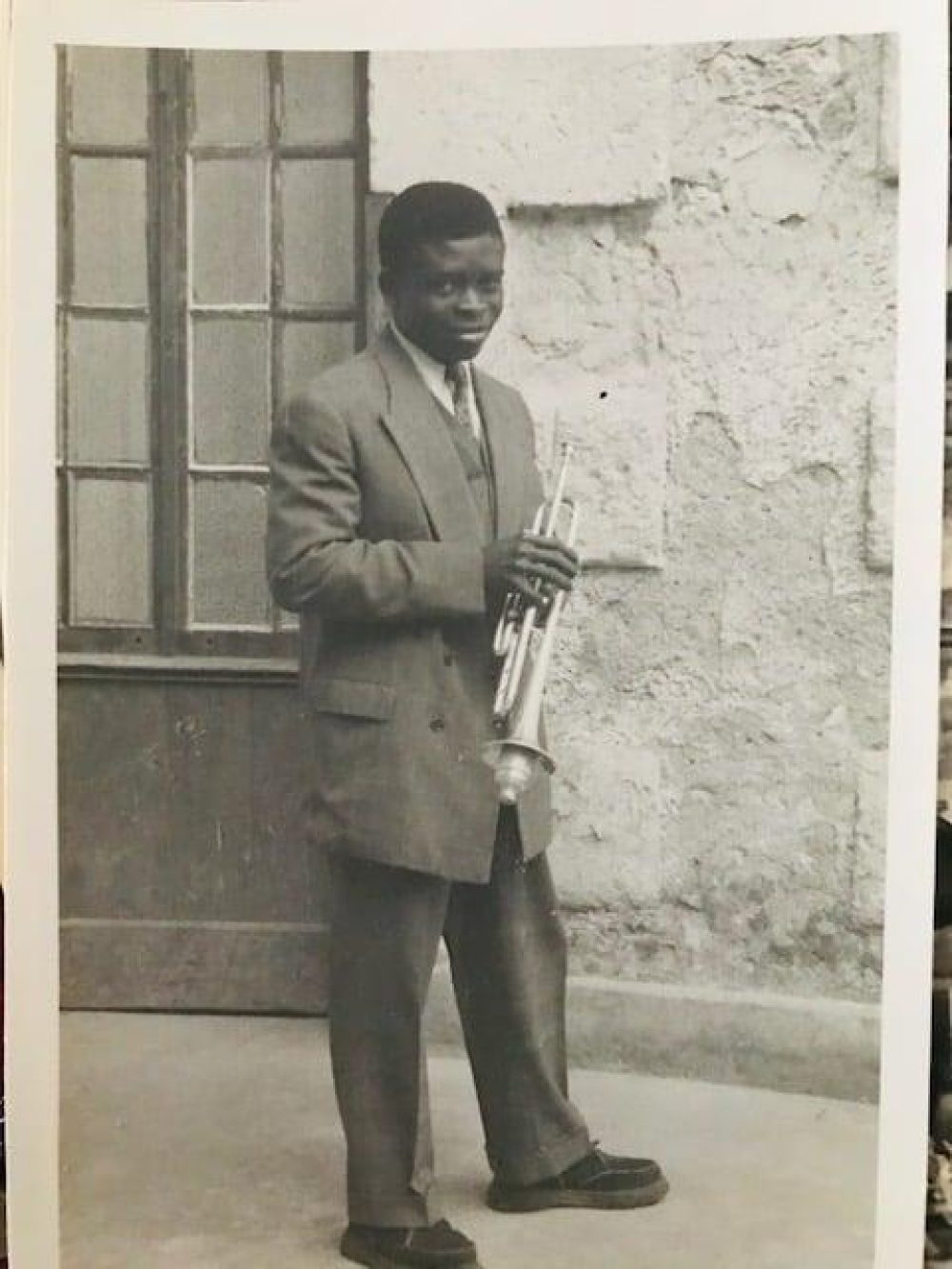

Patrick Bebey is the youngest son of one of Africa’s most prolific and innovative musicians in modern times, Francis Bebey (1929-2001). Born in Cameroon, Francis went on to work in Paris, New York, and Accra, Ghana, where he worked as a broadcaster invited by Kwame Nkrumah. Francis wrote poetry, plays, novels and non-fiction works, but he is best known for his unique musical creations. He began recording in 1969 and produced some 20 albums between 1975 and ’97, blending African traditions with classical, pop and electronic music. He was as comfortable programming an early synthesizer as playing the one-note bamboo flute called n'dehou, a trademark instrument of the Central African Pygmies.

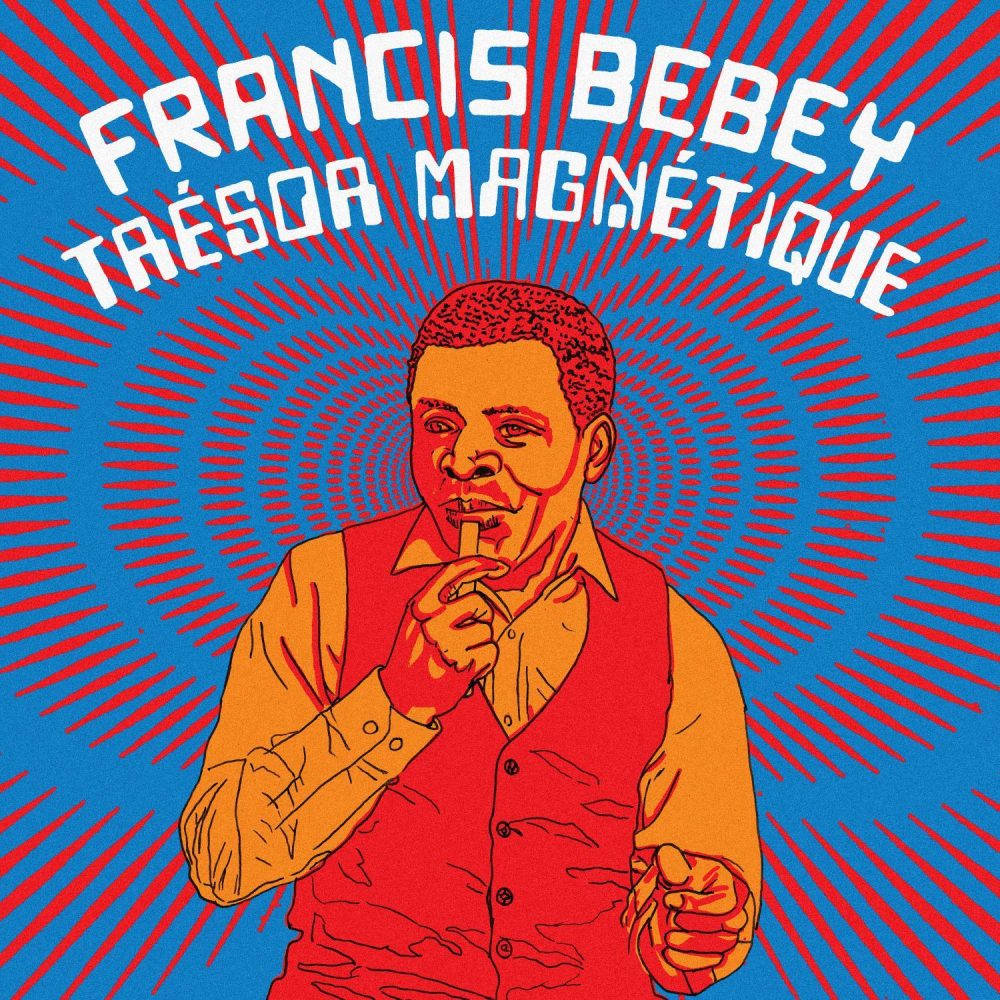

Upon his death, Francis Bebey’s enormous collection of analog-tape recordings, many unreleased, passed to his son Patrick. This year, Africa Seven is releasing Trésor Magnétique, a posthumous collection of 20 previously unreleased tracks. The set offers a kaleidoscopic tour through the mind and imagination of a true original. At times, we hear the maestro laughing and chatting amiably over a bed of delightfully incongruous sounds, both acoustic and electronic. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Patrick Bebey at his home in France to discuss this remarkable addition to his father’s rich catalogue. Here’s their conversation.

And check out Francis Bebey on Bandcamp.

Banning Eyre: Patrick, it's great to meet you. Where am I reaching you?

Patrick Bebey: I'm actually in France, close to Paris, in Fontainebleau, 50 kilometers from Paris.

Well, I've been going back and listening to a lot of your dad's music, and some of yours. We at Afropop Worldwidehave followed your father’s work for years. We've been on the U.S. airwaves since 1988, presenting African music in all its varieties.

Wow! Long time.

I'm really enjoying this new collection, which we will talk about. But first, tell me a little bit of your story. What was it like growing up in that fantastically musical household?

This was just incredible. I mean, my father was a very hard worker, waking up at seven in the morning, having a shower, a cup of coffee, and starting recording or writing a book or practicing the guitar or any other instrument, and it was going on like that till lunchtime. Then he had a break for lunch for 45 minutes or one hour, and then back to work again till dinner time. Then after one hour for dinner, back to work till one, two, three in the morning, then going to bed and waking up at seven.

Unbelievable. Do you live that way now?

No, no, no. I mean, it can happen, but not for a whole week. So from my from my side, I was going to high school and coming back in the afternoon, and usually, when he was recording, we were seeing a sticker on the front door of the house to tell people not to ring the bell, but to just knock carefully, you know? So when I was coming back and there was that sticker, I knew something good is happening. Let me wait and see what will be new this evening. It was totally crazy.

It sounds like he was recording and recording and recording.

Yeah, well, that's why there's so much. It's wonderful.

So at what point did you know you were going to become a musician too. Was there a moment when you decided that, or was it just your inevitable fate?

I think it was when I was 17 or 18. I thought I would like to do it. I started studying the piano when I was 5 years old. So by 17, I had already been playing for 12 years.

You were trained, so it was just a matter of committing.

When I turned 19, my father had an opportunity. He was invited for a tour in Tunisia, and he asked me whether I would like to come. And I said, yes. It was the very first tour of my life. He also asked my brother Toups, who plays percussion and saxophone. And so we went with a bass player called Ahmed Barry from Guinea.

Oh yes, I know of him.

So there were four of us and we had like 10 concerts. It was really incredible. I mean, I was discovering the stage, and some of them were very big stages. We played in Carthage in an open-air theater for something 10,000 people.

Wow!

We arrived in the afternoon. We had no idea whether people would come. There were some seats in front of us, and we thought, “Okay, well, if at least we have the 500 people who can sit there, we’ll be happy.” And in the evening, a crowd, a crowd, a crowd. This was totally crazy. My father had no idea that one of his hits was popular there.

This is the song “Agatha?”

Yes. He knew it was a hit in Africa, but not in North Africa. He had no idea about that. So when we went on stage to start the concert, people were already asking for “Agatha.” My father said, “No, no, no. We're gonna play it like we planned; it will be number 12. Okay?” So we play one song. Small applause. So we play the second one, and same reaction. So after four songs, he says, “Okay, let's play ‘Agatha,’ because I think we need to give them what they want.” We played it, and the people were so happy. They just wanted him to hear him say, “A child, whatever his color, he might be, black, white, green, yellow or red. A child is a child. That’s it.”

That's in the lyrics of the song?

Yes, yes.

Your father also has a novel about Agatha. Who is Agatha?

The story of Agatha started with that novel. Agatha is a black woman, and she's married to her husband. We don't even know the name of the husband, but he's black like her, and together they have a child, which is not a black child. That's the story.

Really?

So the father is probably a white man, and the child is the evidence. The child is two years old, and still hasn't got the local color. But, in fact, it's really an anthem against racism.

Very interesting, but it's kind of a playful, funny story at the same time. I can see why that’s so appealing.

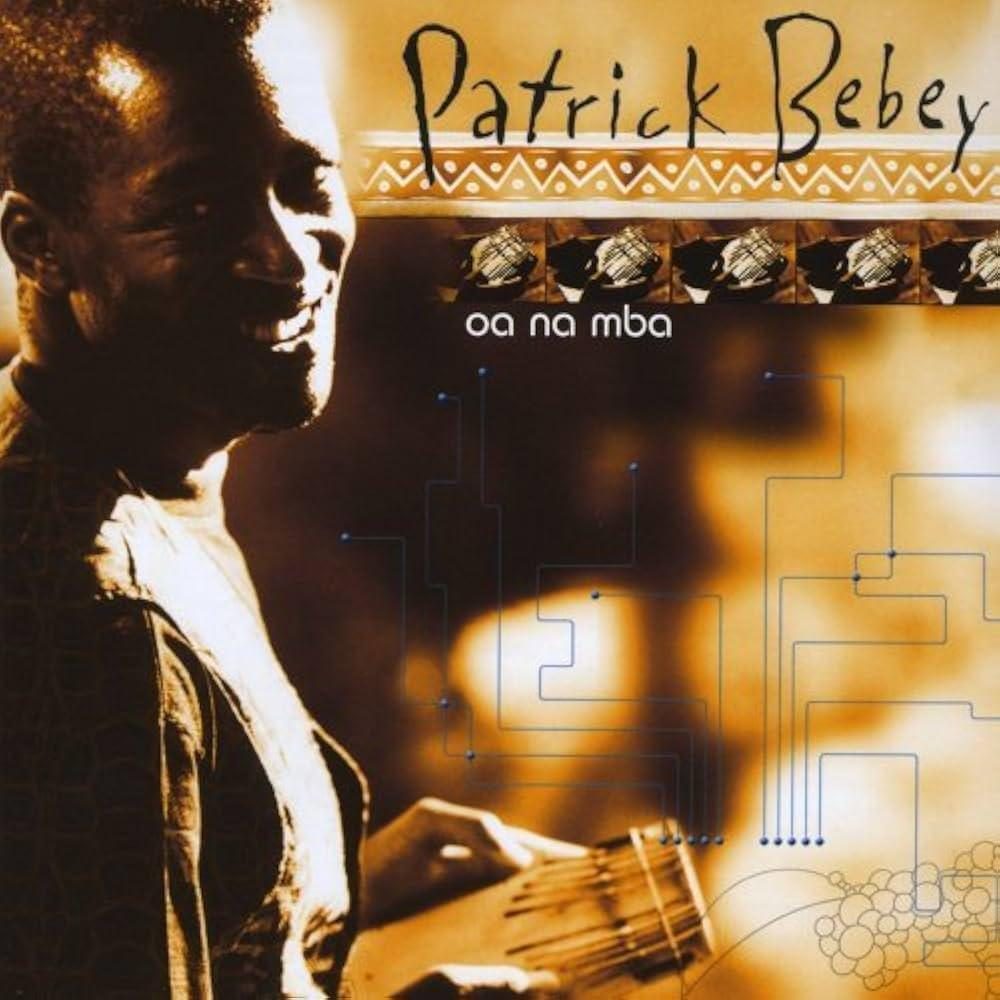

I think I read that the experience of that tour was what led you to eventually make an album together with your father, Dibiye.

Yes, but really it took me 13 more years to make my father agree that we were gonna do it. You know, I was always asking him. We toured in ‘83, and Dibiye we recorded in ‘96. The thing is my father… He really enjoyed asking me, “What do you think of this? What do you think of that? Do you think it's okay like this? Do you think it's okay like that?” So sometimes in the beginning, I was pretty shy. I had no experience. But after a few years, okay, I could dare telling him what I thought.

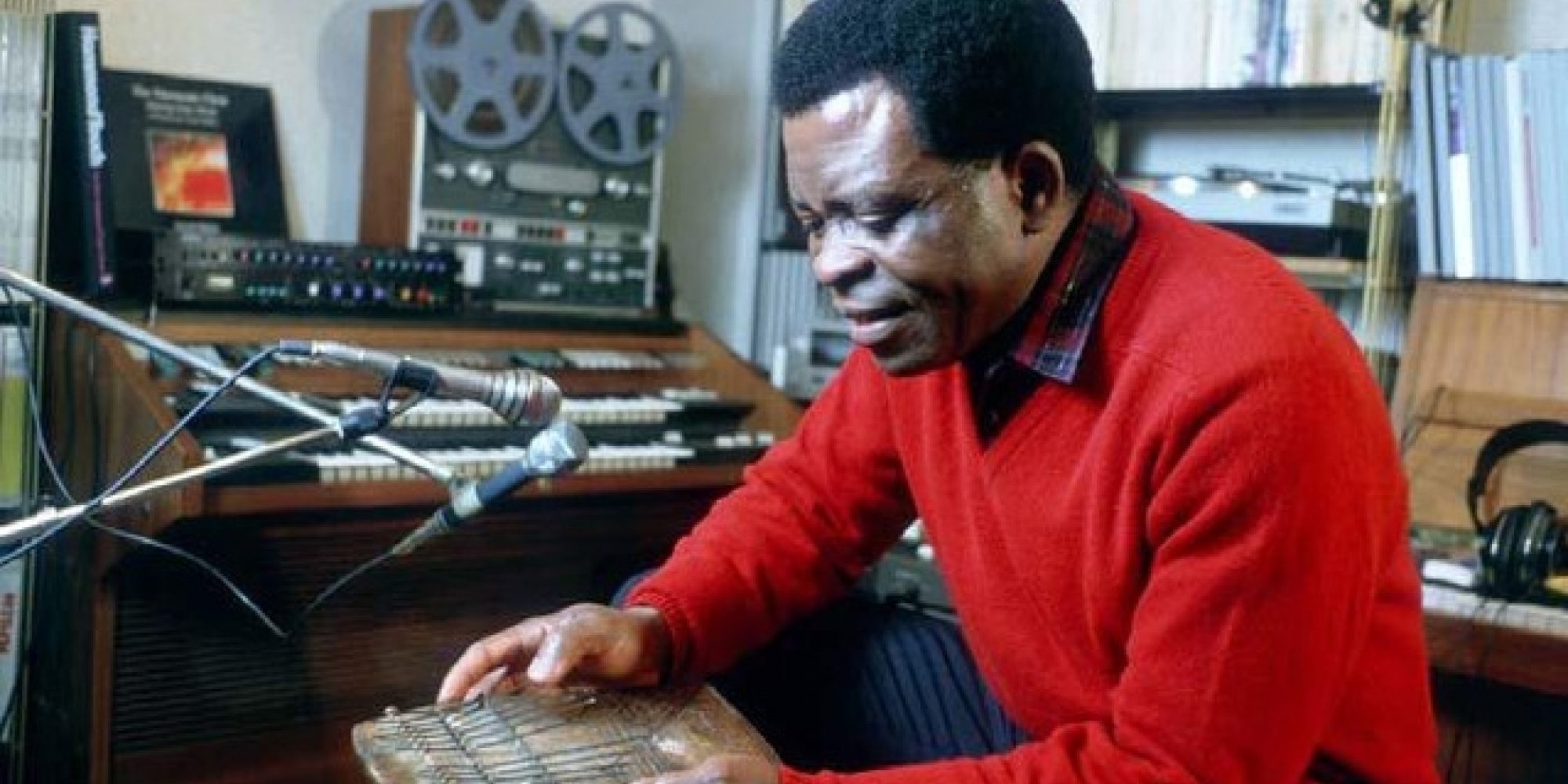

He was recording at home, you know. He had a four-track recorder, so he was recording four tracks, then mixing them in stereo, and then adding two tracks and mixing the four tracks in stereo again, and then adding two more tracks. So it was a long, long process. And also, I wanted him sometimes to ask some other musicians’ advice, or just to hear the way they would play on this song. I was thinking it could be interesting to mix with other musicians.

And he didn’t want to do that?

The problem is, he had had some bad experiences with record companies. In France, he had recorded for Philips. His very first record on the market was for Philips. And the problem is, they sold many, many albums. They made a lot of money, but he didn't get one cent.

Really? Nothing?

Yes, nothing, but really nothing. That's why he decided that he was gonna create his own record company. But he didn't have the financial possibilities of a big record company. So he bought a four-track recorder. He was good at using microphones, and this is what led him to kind of do it all himself.

So he didn't play that much with other musicians ever?

No.

Just that one tour in Tunisia?

We had that tour. Then we had few other concerts with one or two other musicians, but most of the concerts, he was playing alone, and most of the records he was recording alone by himself.

And this all goes back to that distrustful experience he had with Phillips

Yeah, yeah. He was explaining to me that, “You know, at least, I do it my way. Okay, I don't earn a lot of money. I don't sell many, many records, but at least each record I sell, I get 100% on it.”

I guess one advantage is that this let him just completely be himself and pursue his own path. I was listening back to his album of African Electronic Music from 1975 to 82. And I was thinking how he was a Afrofuturist before there was any such word. He really was a pioneer of this thing that everyone talks about now, Afrofuturism.

Totally. Yeah, yeah, that's true. When I was telling him we could go to a studio and do it together, he would just say, “I don't have time for that.” Because he was recording from the ‘70s until his death. He recorded some 40 records. I mean, one a year, sometimes two records in the same year.

And there's probably lots of stuff that never got released, right?

Yeah. He so much enjoyed being totally independent, no artistic director who will tell you, “No, you should like this. Do it like that, do like this, and change this. And no, I don't like these lyrics…” No, no. He could just edit whatever it was that came into his mind. He told me, “I do it my way. Anyone who feels like doing it his own way can take the music and do it his way..

Well, it's not like he needed any guidance. He had plenty of ideas, right?

Yeah, sure.

So this album that's just coming out now, Tresor Maganetique; how did this collection come about?

Well, the thing is, I have the tapes at home. I have all the tapes of my father. But for me, it is very difficult to listen to these tapes. You're probably going to think I'm crazy, or too sensitive. But when I listen to my father singing, 90% of the time, I start crying.

It's too emotional.

Yeah, because I hear his voice. And sometimes I feel that in the evening, when I get back home, I want to give him a call to discuss about something. And then I realized that, no, I can't give him a call anymore. You know, we were really close. He was my father, but he was also such a good friend.

We were five children. I am the youngest, and I can't explain why. But there are many things he decided to share with me and he has never shared with my brothers or sisters. It was like that. And he would tell me, “Don't ask me why I'm telling you this or that. I don't know. I just feel that you're the one I have to tell.” So we were very, very close, and especially in the last three or four years of his life.

He had a heart attack, and they did a big operation on his heart, and after that, he had a problem with his throat. They put him on a breathing machine. But it damaged his vocal chords, his strength, and he could not sing. So in the last years, he was calling me and saying, “I'm having a tour in Germany and I can't sing. I don't want to do the whole show without bringing some of my songs. I would like you to be my singer.” So we started touring as a duet and I would sing.

You would sing his parts.

Yeah, yeah. I was lucky because I had been singing since I was five years old, 20 years almost. But the thing is, I was scared of singing, because when you sing… I feel when I sing that I am naked in front of people.

You didn’t see yourself as a singer,

It was very difficult, but he told me, “No, really, you have to do it. I know you can do it and make people feel an emotion.” It was a big, big work on my side. But because of him, I think I really became also a singer.

Okay, so you felt more comfortable singing after this experience.

Yes.

Well, that’s fascinating. So Patrick, I don't have the full notes for this album, but I see that it's divided into groups of songs, sections A, B, C and D. I guess those come from different eras in his career. Is that right?

No. I think they just decided to do it that way, to make something nice. You were asking me how much I was involved. So I was involved because I had the tapes, I guess. But I said, “I'm sorry. I'm not giving any advice. For the songs, you have to choose.” It's impossible for me, because I have hundreds of reasons why I want this one and this one and this one. But we are five children. Then my brother would say, “Hey, why didn't you pick this one?”

Ah. I see.

I just said, “You make the decisions. No one in the family will complain about your decision.” So they chose, and when they sent it to me, I said, “Perfect.”

Well, it's a wonderful record. It goes all kinds of places. I have to ask you about one of your own songs, “Ponda.” I hear in this song—and I heard your cameo on the Arcade Fire song “Everything Now”—the sound of the Pygmy flute. This was a sound your father loved, and celebrated on “The Coffee Cola Song,” a classic, which appears in a new version on this album. I'm remembering that when I was a teenager, and I didn't know much about African music, I once walked into a record store and said, “Give me something brand new that will surprise me,” and they gave me Herbie Hancock's Headhunters, and there was that Pygmy flute hook on the song “Watermelon Man.”

You know, the thing is my father was working for Unesco for years. He was the director of the music department of Unesco. So he was traveling a lot, especially in Africa, collecting some traditional music and bringing it to be released by a record company called Okora.

Yes, of course. Wonderful collection. Yeah, we have a lot of Okora releases in our archive.

He was really open-minded. We were listening to many kinds of music, except hard rock. I have to say there was no hard rock. But we were listening to the Beatles. We were listening to Milton Nascimento, Johann Sebastian Bach. And all this traditional music that he was finding in his work.

That’s quite an education.

Yes, and he started very early to play that Pygmy flute. And it was fascinating. This flute plays one note. All the other notes you have to add with your voice. And he started recording it. Then one day, I was playing with some musicians, and they asked me, “But did you do this because of Herbie Hancock!” Because of the flute.

This happened to me also because of the thumb piano, the sanza. I was playing a concert in Germany, and a young lady came to me and said, “Your concert was fascinating, especially the songs you played with that thumb piano. Do you use it because you heard it on the last album from Gloria Estefan?”

Oh, really? I don’t know that record.

Well, the record was 20 years ago. But, you know, I played this instrument since I was 16 years old.

Well, this is what happens when things get popularized. People get all kinds of funny ideas about the timeline, and where things started.

But in a way, it hurt me, because, you know. I was thinking that people don't understand that this is totally a traditional African instrument. I mean, I have lots of respect for Herbie Hancock for Peter Gabriel, but they didn’t discover these things. I met a festival organizer in the South of France, and the guy was so nice to me. We were talking, talking, talking. It was nice, nice, nice, until the point when he said, “You know, for me, it's a pity that many African musicians electronize the music.”

I said, “What do you mean by electronize?”

“You know. They add microphones on top of the of the kora, or on top of the sanza and all the traditional instruments.”

And I said, “Man, I'm sorry, but I have to tell you something. I put the microphone on all my sanzas, because I play with a drummer and I want to be heard. I also live in this century and I know that there are effects pedals that I can use with my sansa. I put the flanger on top of it, and distortion, and I like it. I do it because I live in this century.”

Of course. You don't have to be frozen in the past. Your father’s album Psychedelic Sanza says it all.

African music can’t be frozen in the past. It's good that we have these roots, but we have the right to develop.

I play guitar, and I've traveled a lot in Africa learning guitar styles, and I worked for a while with an American woman who goes to Zimbabwe a lot to study music. She plays the mbira dza vadzimu, the Shona style, very well. But there are people here in this country who have also gone there and studied that music, and just like the festival promoter you just talked about, they don't think you should put any effects on it. You have to play it just the traditional way. And this woman is a rock ‘n’ roller. She wanted to play through a distortion pedal, and what have you. And so we kind of experienced a little bit of that purism. And it's even worse when it's coming from an American who isn't even from the culture. They just learned it, and they somehow think that they're the guardians. You are right. Musicians have to move with the times, and certainly your father was an incredible example of that.

I'm from Africa, but sometimes I dress like a European with a suit, and sometimes I dress with an African shirt. But I don't have to. It's not because I'm African that I have to jump on stage with an African shirt. No, sorry.

I remember in the ‘80s when a lot of African musicians started using drum machines and there was a lot of complaining about that. I myself would say, “You have such rich traditional rhythms. When you put the beat in a drum machine, it becomes sort of rigid and soulless.” Sometimes the response would be, “Oh, you Westerners! You want to keep us in the past.” Well, it wasn’t exactly that. I just thought those machines compromised the aesthetics of the rhythm. But look at what's happening now. The kinds of artists who started out with drum machines are now the biggest pop stars in the world, especially these young artists out of Nigeria. Drum machines and synthesizers were the beginning of their process of learning how to produce at an international level. And now you have these amazing success stories. What do you make of these big artists out of Nigeria and South Africa who are filling stadiums and dominating YouTube with Afrobeats and amapiano?

I'm very happy for them. I think we deserve it. Like we said, they live in this century, and they want they want their music to be heard, and people are listening to their music.

Yes. It’s working.

It’s working, and I'm very happy about it. Very, very happy.

Good for you. I feel that way too. Personally, I still like the older stuff better, but it’s great to see that all that experimentation has led to a place of real success. It's a very interesting time for African music now.

It is.

So what are you up to these days?

Right now I'm recording with a friend from Argentina. We are in a studio recording together. I’m giving him a hand. But really what I'm looking forward to is trying to promote the album. In September, I start touring a bit with it, and I hope I can bring it to as many countries as possible.

We’ll be on the lookout for it.

It was a long process. I’ve never rehearsed like that for a record. We did almost one month of rehearsal.

What's the name of the Argentine musician?

His name is Jorge Borsi.

And it’s just the two of you.

With a friend from Uruguay called Pájaro Canzani. Pájaro has a very nice studio in the countryside here in Fontainebleau. So we stay there when we record. When we are tired, we go to bed, and then next morning we start again. It's really nice, very quiet. And Pájaro is a very good producer also.

Well, I look forward to hearing that. Uruguay has an interesting connection to African music.

I had the opportunity to go to Uruguay two or three times, and it was amazing.

Candombe.

Exactly. The guys were playing those big drums in the street. It's just incredible. Suddenly, you're not in South America. You're in Africa.

Well, it's really wonderful to talk with you and to meet you. And I really appreciate all these stories about your father.

Thank you, Banning. Thanks for inviting me.

My pleasure. Good luck with everything, and stay in touch.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles