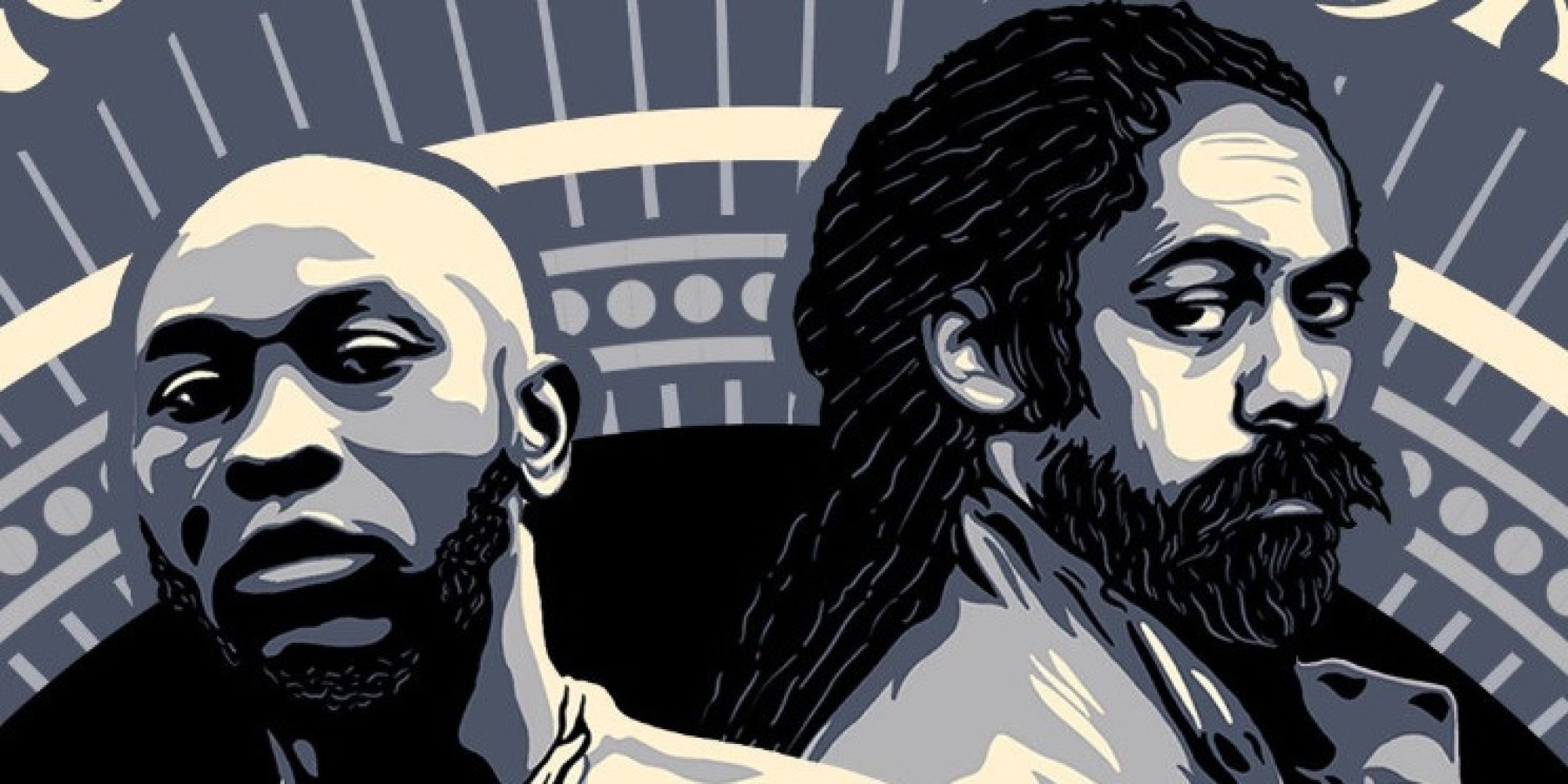

On June 26, Seun Kuti and Damian Marley released “Dey” –jazzy, funky, and indicative of the sound that defined Nigerian star Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat.

Seun, Fela’s youngest son, has been carrying the mantle of his father’s sound since his death in 1997. Seun first appeared alongside his father in 1991 at the Apollo Theater in Harlem in New York City. He officially “inherited” his father's band, “Fela & Egypt ’80,” at the young age of 14, though his earliest records would come only in the following decade. Despite the formidable legacy of his father, Seun has consciously made an indelible mark as an artist in his own right. He has collaborated with a variety of notable artists from Carlos Santana (“Black Times,” 2017) to Janelle Monae (“Float,” 2023), as well as half of hip-hop group “The Roots,” Black Thought and VIC MENSA (“Bad Man Lighter 2.0”).

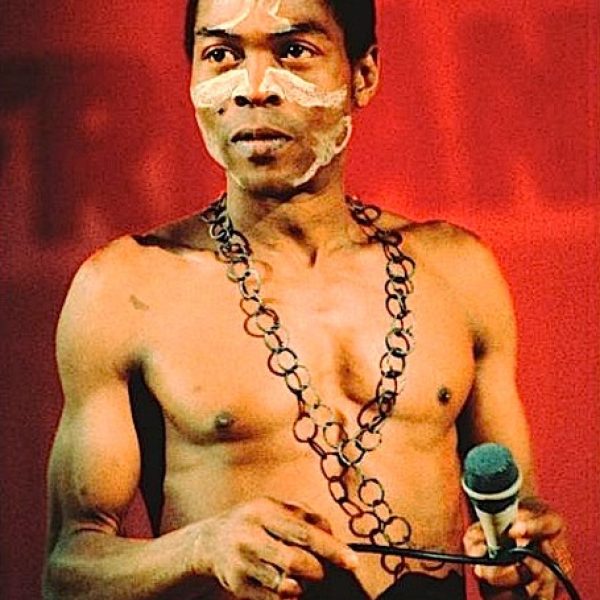

In a 2011 interview with The Guardian, Seun said he had declined the leading role in the hit Broadway show Fela! because, “It would just give ammunition to those who say I am copying my father.” However, he nevertheless honored his father’s legacy when he released his first album, Many Things, under the name “Seun Kuti and Fela’s Egypt 80.” And while Seun continues to create space for himself as an artist, his music and persona is undeniably influenced by his father.

This is a fate shared by Damian Marley, also the youngest son of his father, the legendary Jamaican reggae star Bob Marley. At the same time, while Seun got to spend time as a youth with his father at the Kalakuta Republic, Damian was just two years old when his father died. Nevertheless, Damian was immersed in the musical culture not only created by his father, but of the myriad other reggae, ragga, and dancehall artists based in Kingston, Jamaica. Yet, like Seun, he developed his own sound, which, while honoring the roots reggae sound of his father, has ventured out into the sounds of hip-hop, rap and reggaeton, as well as various forms of African music. This collaboration with Seun is part of Damian’s ongoing engagement with music on the African continent, from Ethio-jazz influence on his 2010 collaborative album with Queens rapper Nas, As We Enter, to recent collaborations with contemporary African artists like Burna Boy and Afropop Board of Directors member Angelique Kidjo (“Different,” 2019) as well as Wizkid (“Blessed,” 2020).

Fela Kuti and Bob Marley were both at the explosive beginnings of their careers in the 1970s, and while there was never a collaboration between the two artists, the common denominator is the political and social quality of their art, a characteristic passed on to both Seun and Damian. Fela and Bob carried their Pan-African doctrine from alternate sides of the Atlantic in their music, but a certain spirituality, unconventional but certainly attractive, was embedded in both of their music. In tune with the 1970s atmosphere, their lyrics were socially and politically charged, lambasting corrupt politics in their native nations and abroad. Fela’s Kalakuta Republic compound was reminiscent of the Rastafarian compounds that, ironically, characterize apolitical Rastafarian sects who opted for separation and steadfast patience for deliverance rather than direct engagement with corrupt politics. Then again, the Rastafarian compounds were also extensions of the self-ruling maroon communities of early modern Jamaica, which maintained freedom alongside, but hidden from, a British colonial society. Thus, between Fela and Bob there was a spectrum of social and political awareness and activism.

These influences are heard in Seun and Damian’s music, and certainly in “Dey.” Damian’s “chatting” or “rapping,” complements Seun’s saxophone. Damian lyrically opens the song with, “love, love, love, love!” and the listener might assume through the bright music that it will be a record that speaks of idyllic peace and unity or perhaps about sweet-nothings. Yet, midway through, Seun refrains,

“This world is full of romance, this world ain’t got no love”

The song’s lyrics offer a critique of superficial attraction in relationships on social media, and with the self. Yet the voices of both Seun and Damian are all but drowned out behind the cacophony of instrumentation suggesting that really, themusic is the message. While lyrics are central fixtures to the legacies of both reggae and Afrobeat, it is the broader sonic atmosphere that provides the supercharge. This is why genres like reggae and Afrobeat can imbibe diverse lyrical messages while the sound remains consistent and identifiable, signifying connection to a revolutionary era.

Sonically, Afrobeat and reggae are both informed by sounds and music technologies coming out of the United States. American Rhythm & Blues was the most popular genre in 1950s Jamaica, influencing the development of a national sound known as ska, which evolved into rocksteady and then into reggae. And while reggae remained a characteristically Jamaican genre, there was a distinction made between Bob’s sound, which resonated with European and American audiences, and the more rough-edged music that became more popular within Jamaica, suggesting that Bob’s sound was still in some ways shaped by the Western ear. At the same time, in Jamaica, musical equipment from the United States was being imported into studios, and the foundation for what became the reggae subgenre dub, and later dancehall. While reggae took the United Kingdom by storm, dub would become part of the foundation for American hip-hop in the 1980s as Jamaican immigrants settled across New York City.

While Bob was meeting success across Europe and the United States in the ‘70s, Fela had reworked his band as Nigeria ‘70 while traveling through the Black Power U.S. in 1969, developing a relationship with Black Panther Party member Sandra Smith Isadore. Fela’s own mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, also imbued his musical formation with political consciousness. Funmilayo was famously an activist in the 1950s during the first wave of African independence movements from Algeria to Ghana. Fela’s formative years in music were also profoundly shaped in the late ‘50s by his experience in London where he was exposed to jazz music, including John Coltrane, Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins.

Seun in many ways carries on the sonic atmosphere of his father’s work. The legacy of political activism is tethered to the legacy of the music. The specter of his father’s artistic and political legacy is also reflected in the fact that Nigeria was run for over 18 years after Fela’s death by the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), led by military official-turned-presidents, Olusegun Obasanjo and Muhammadu Buhari, who were antagonists towards Fela and his politics. It was Fela’s vocal defiance in his struggle against corrupt politics in Nigeria that garnered the ire of such powerful officials.

Seun’s artistic activism is thus a direct legacy of his father’s, and part of the ongoing evolution of Nigerian politics and art. Yet Bob and Fela had distinct approaches to politics; while Fela was in a sense honored to have Nigeria’s politicians as enemies, Bob’s diplomatic nature could arguably be ascribed more to his Rastafarian reverence for Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I. Selassie was noted for his diplomacy and dexterity in conflict resolution between African nations. He was a co-founder of the Organization of African Unity (1963). Bob at one point similarly became a mediator between the warring political factions, an experience that transformed the lay Jamaican into a kind of mercenary, a legacy that still haunts Jamaican politics today. Bob famously made opposing politicians Michael Manley and Edward Seaga hold hands at the 1978 “One Love Concert,” and he constantly called for peace in Jamaica, a position that almost cost him his life in 1976 in a shooting that officially sent him into a self-imposed exile in Europe.

Damian also carries the airs of his father’s sonic atmosphere, which, despite its simple yet defining “one-drop” sound, carried with it revolutionary messages of revolution, liberation and love. Indeed, many people now associate reggae with themes of relaxation, marijuana, and good vibes thanks to hits like “Positive Vibration,” (1976), “Three Little Birds” (1977) and “Jammin’” (1977). But these were few amid a sea of songs with far stronger messages like “War” (1976), “Exodus” (1977), “Burnin’ and Lootin’ (1973) and “Them Belly Full” (1974). Damian himself has expressed fondness for his father’s “grittier” sound, and this can be audibly observed in his sampling and remixing of some of Bob’s most politically charged songs, including “Crazy Baldhead”/“Me Name Jr. Gong” (1976/1996) and “Slave Driver”/“Catch a Fire” (1973/2001).

Whatever approach they chose in their music and politics, Bob and Fela both left lasting legacies that Seun and Damian have carried on in their unique ways. Head-on engagement with politics seems to be an art of the past for the entertainment world. Seun and Damian nevertheless implore their listeners to be wise to the corruption of society and the corruption of oneself in their collaboration “Dey.”

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles