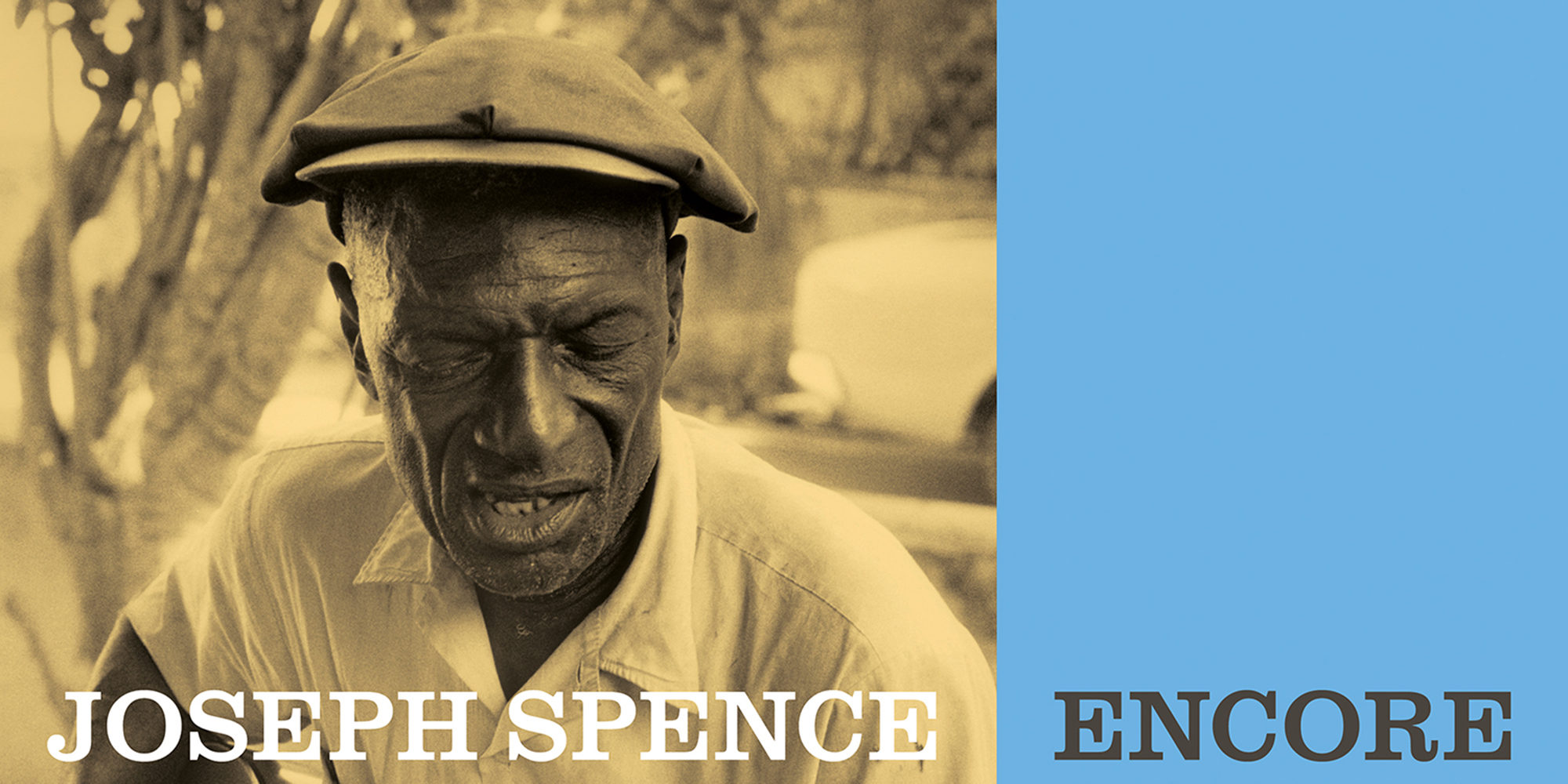

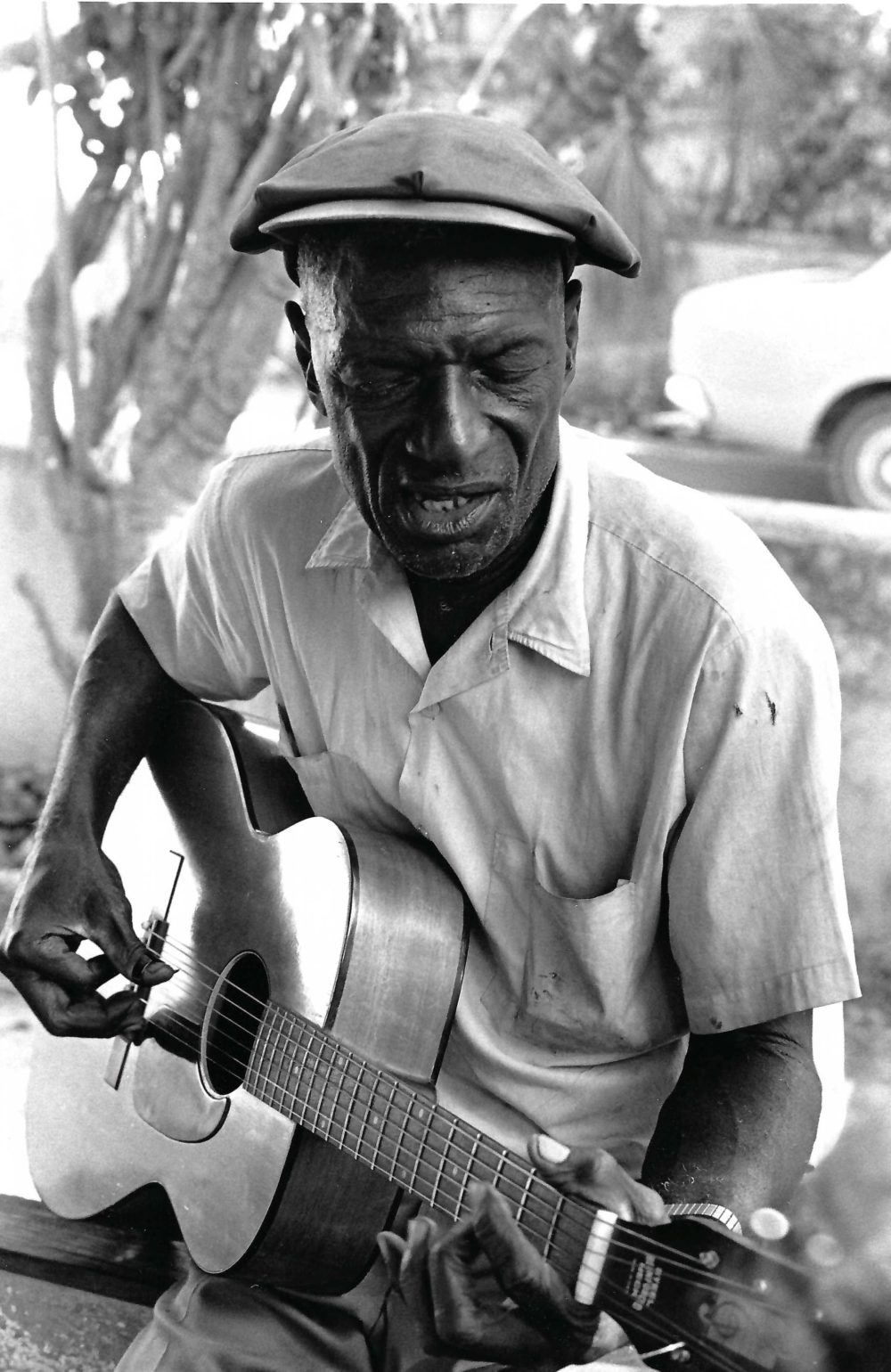

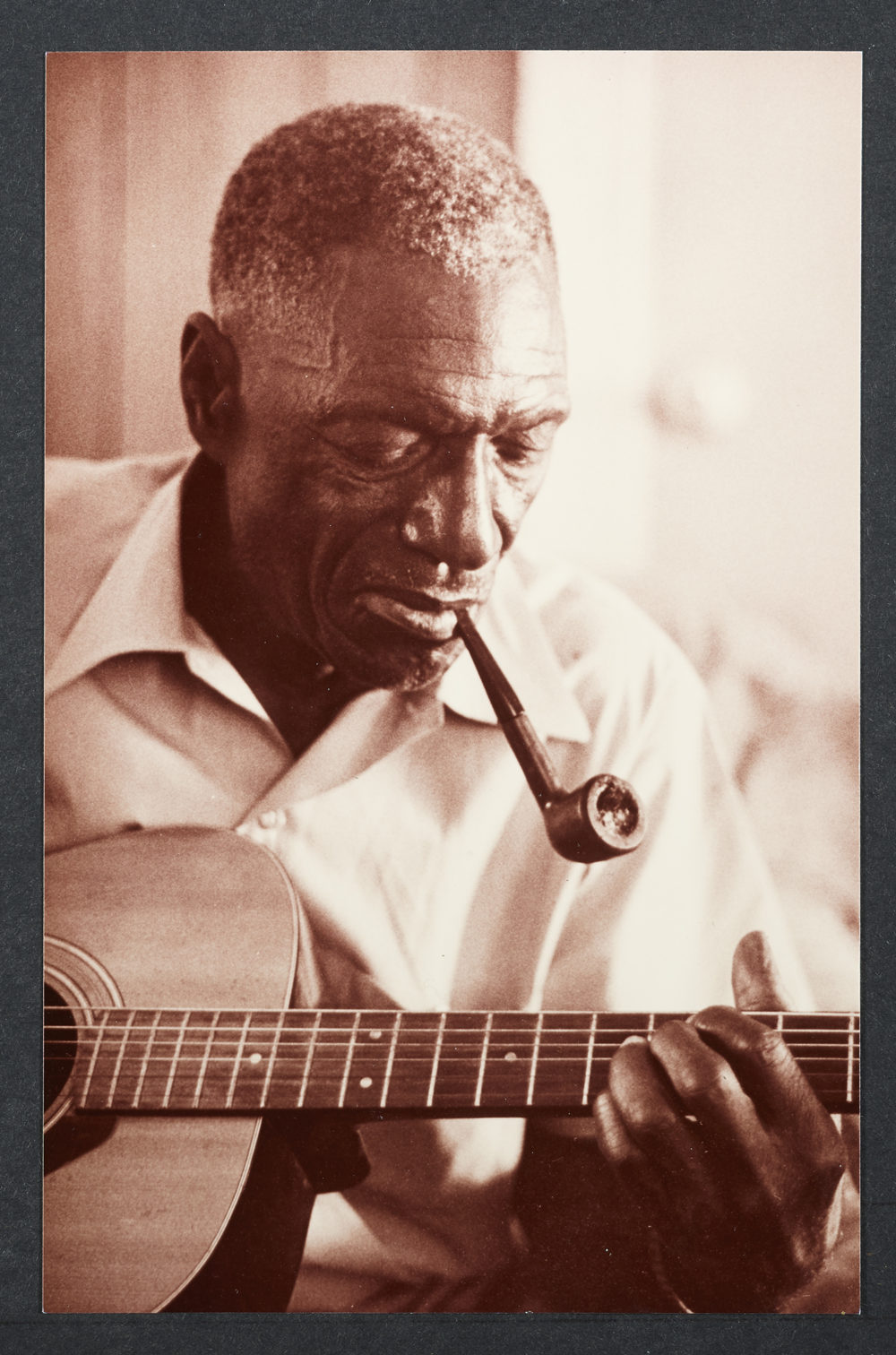

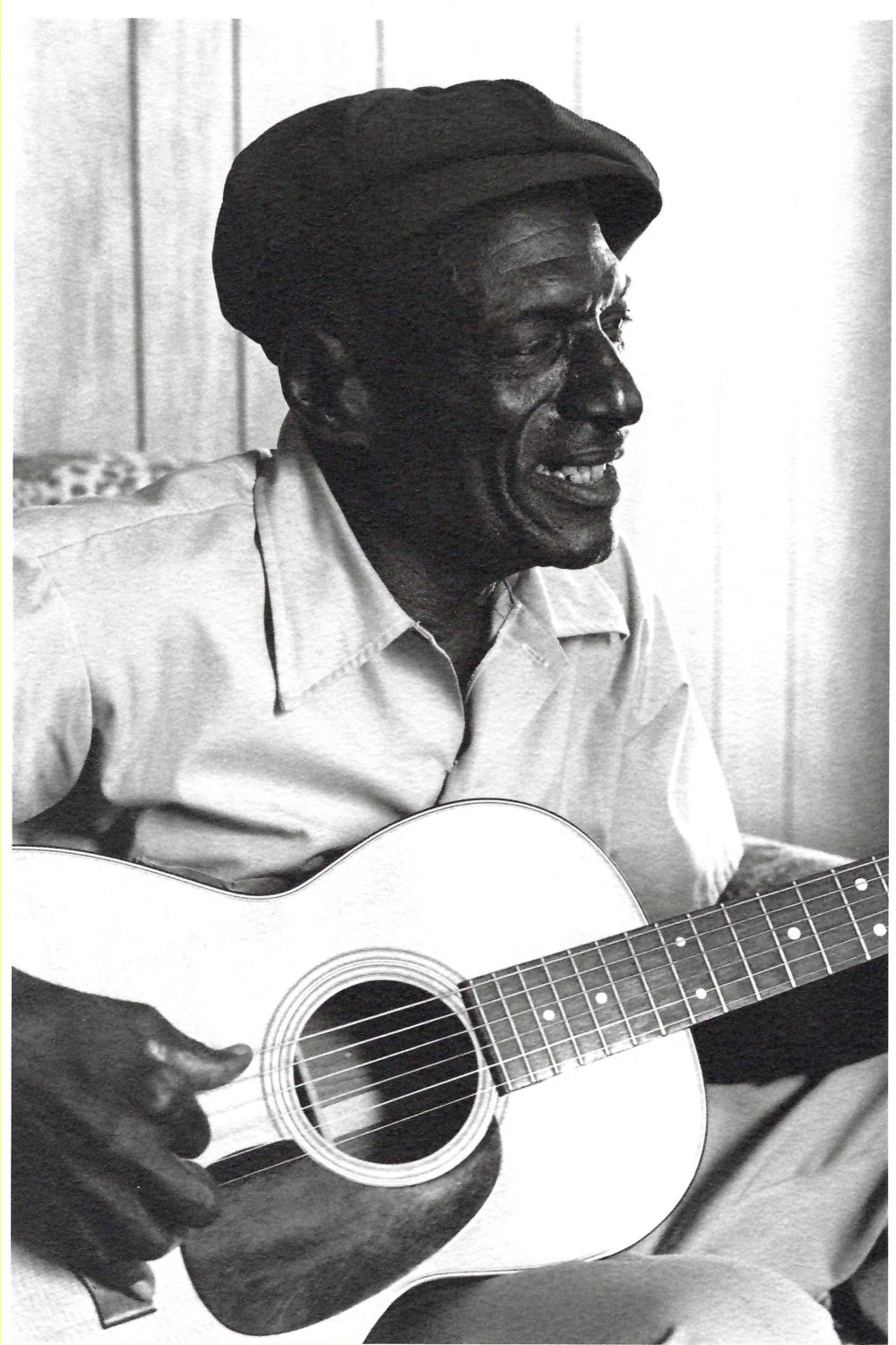

The music of Bahamian guitarist/vocalist Joseph Spence (1910-1984) is unforgettable to anyone who has heard it. His guttural voice—half gospel, half grunt—is buoyed by an utterly unique fingerstyle guitar playing that moves with the determination and funk of an old jalopy. Spence’s repertoire mixes songs you’ve known all your life with those you wish you had. In the deepest sense, his art traces back to the 17th century, when British colonialists moved African captives back and forth between the Bahamas and the Carolinas, blending cultures along the way. Starting in the late 1950s, when his music was recorded and heard in American folk music circles, Spence became a beloved global folk icon.

In 2021, Smithsonian Folkways has released a new collection, Encore: Unheard Recordings of Bahamian Guitar and Singing. The music was recorded and the album produced by Peter K. Siegel. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Siegel in New York to learn more about it.

Banning Eyre: Nice to meet you Peter. I have to tell you I have long been a fan of Joseph Spence. I don't know a heck of a lot about him, but he's one of those artists that you just have to love. The music is so unique, so disarming, so delightful. And this album is a nice addition to the catalogue. You are lucky to have known the man. So tell me, how did this all happen?

Peter Siegel: I am lucky. When I was a teenager, which is getting further and further away, I volunteered for a group in New York called the Friends of Old Time Music. This was a rather informally put-together group, but we did something that was very unusual at the time. The Friends of Old Time Music brought real, community-based folk musicians to New York City to perform for folk audiences who had previously heard some fine music from, say, Pete Seeger or Odetta, but not from the people from the actual places where the music arose.

This would be the 1960s.

Yes. Beginning in 1961, I began to volunteer for them, which would've made me 17. And then in 1965 I was still volunteering and part of the volunteering was being available to show the musicians around town when they came to New York. So I got the incredible assignment of taking care of Joseph Spence for a day when he got to New York, as well as his sister Edith Pinder, who is a great singer. And we had a fabulous time. He was just like his music. He was exuberant and happy and inquisitive. Wanted to know everything.

I took him to the top of the Empire State building, to the observatory up there, which I thought would be his kind of thing because it would give him the opportunity to see the world in a very new way. And he loved it. He was an incredible guy, just an incredible man, as well as an incredible musician. And of course he couldn't have played the musician he played if he wasn't an incredible guy. But that's how I met him.

I was also the person who was recording the concert for the Friends of Old Time Music, so I recorded his concert, and I recorded him at my home, which was my parents’ home at the time because I was still living at home at that age. Then later, Jody Stecher and I went to the Bahamas and we recorded a lot of great music. The new album includes previously unreleased tracks from the concert, from my apartment, and from Joseph Spence's home in the Bahamas. So I'm really happy with it.

Had Joseph Spence ever been to New York before?

No. He had been to the United States doing what was called “working on the contract” during the 1940s. And the contract was a federal program that allowed people who live in other countries—which turned out to be the Bahamas and other islands in the Caribbean—to come as guest workers and do agricultural work while American men were away fighting in the war. It was an opportunity for very poor people in the Bahamas to make some good money and come to the United States. So he came in the 1940s for a couple of years. But he never came to perform until 1965.

So that wasn't just his first time in New York but his first performing the United States at all.

Oh yeah. I'm not even sure he had ever ever performed in a formal setting like a concert. I don't think he had.

So how did the Friends of Old Time Music know about him?

The Friends of Old Time Music… I hesitate to call even them an organization because it was very informal. It was run by three people: Ralph Rinzler, John Cohen and Israel Young [FOTM’s official bio also cites Margot Mayo and Jean Ritchie as founders], all of whom were very plugged in one way or another to the idea of presenting real traditional music. And I think we all knew about Joseph Spence because in 1958 Sam Charters went to the Bahamas and met Joseph Spence and also recorded some other great singers like Frederick McQueen and John Roberts. Sam came back to the United States and put together a couple of albums of Bahamian music that were released by Folkways Records, Moe Asch’s label. And the first volume in that set was entirely devoted to Joseph Spence. It came out in 1959. I heard it. Everybody heard it. And it blew us away. I mean, what can I tell you?

Of course. So unique.

So the Friends of Old Time Music, Ralph Rinzler, John Cohen and Izzy Young, they had presented a lot of American music. That was the first group to bring Clarence Ashley to perform in a concert or Doc Watson or Mississippi John Hurt, lots of people…

It may not of been an organization, but it certainly has a legacy.

It does. O.K., but the history… This is maybe more than you want to know.

No, by all means. I'm curious.

By 1965, Ralph Rinzler had been hired by the Newport Folk Foundation, which was an outgrowth of the Newport Folk Festival, and Ralph had been hired to do field work for the festival. That was also a paying job. Friends of Old Time Music was just a bunch of guys in a coffee shop basically. Anyway, Ralph was called the director of Fieldwork Programs, a very fancy title from the Newport Folk Foundation. And he was able to use his influence to put together a trip by Joseph Spence and several other singers from the Bahamas.

They knew about Joseph Spence from the Folkways recording, but Sam Charters had met Spence for just a couple of hours. He didn't really know him. So Pete Seeger volunteered to go to the Bahamas to find Joseph Spence. And he did. He found him performing for some tourists on a dock in Nassau. Pete Seeger arranged for the Friends of Old Time Music and the Newport Folk Foundation jointly to bring Joseph Spence and a few other musicians from the Bahamas to the United States to perform.

Hence this tour. Where were the concerts?

It was a short tour. There were three cities involved. Philadelphia, Boston and New York. And the New York concerts which are recorded was at the New School, and what is now called the West Village.

I want to talk about Joseph Spence's art, but first a little bit more about you. How is it that you got so interested in this? I'll just preface this by saying I grew up in New Jersey a little later. I was born in 1956, and my mother was into folk music. She had Leadbelly records and the like. So that was in the air for me at an early age. But I'm curious. How did you come to it?

Very much in the same way. My parents had been part of an earlier folk music boom in New York in the 1940s. They lived in the Village. They had apartments… And this is all hearsay because I wasn't born yet. But they lived in apartments on Jane Street, and Horatio Street, and they were in with that crowd of people. They lived in the same building as a guy named Millard, or Mill, Lampell who was a member of the Almanac Singers. Mill Lampell was the writer who wrote the words, often with Pete Seeger, to songs like “Talking Union.” And he co-wrote “The Good Ship, Ruben James” with Woody Guthrie. So he knew all those people, and they got to meet everyone.

My father told me an amazing story. My father is no longer with us I’m sorry to say. But he told me that when he was in college at NYU sometime in the mid-‘30s, he took a course called Balladry, which is as close to a folk-singing course as you could get. The professor, a folklorist named Mary Elizabeth Barnacle, was also involved with Bahamian music, but she brought Leadbelly into play for the class. And this apparently was a huge experience for my dad, just sitting in a classroom—I can't even imagine—Leadbelly comes in and bang!

So they knew all those people. They had all those old 78 RPM records. So I got involved with it. And I connected it somehow to music that was popular among my own friends at that time. I connected it with Johnny Cash. In my mind I really understood that the Everly Brothers were doing something that was similar to what the old folk singers had done. So I was into it. I started playing guitar when I was, I think, 13. My dad took me to a store called the Folklore Center in New York. The proprietor was the same young Izzy Young who would later become part of the Friends of Old Time Music.

So I knew all these people; I knew Ralph Rinzler; I knew John Cohen; I knew Mike Seeger. All these people were doing this kind of work, and so by the time they were starting the Friends of Old Time Music I was old enough to help out. That's how I came to it. Very much like your story.

You had the gear to record the concert. I assume you were using the same gear to record in your apartment. What were you using?

By that time I had a really good tape recorder. I had started with tape recorders you may remember like Wollensak and then I improved with a Tandberg. But by 1965 I had a Nagara tape recorder, a Nagara 3B, and it had very good microphone called a Sony-C37A condenser mic. So actually I was able to make a good recording. The other thing about making good recordings is that if you put a mic in front of a real master musician, the recording pretty much takes care of itself. They already know how to produce sounds that work. So that was no problem.

I guess the main issue would be getting a balance between the instrument and the voice and that's just a matter of placement, right?

Yes. This is an aside, but when Sam Charters first recorded Joseph Spence, he was really interested in the guitar, and he saw the vocalizations as sort of incidental. So if you listen to the Folkways records, you will see that the microphone is right on the guitar, and you almost hear the singing as a background accompaniment. By the time I recorded Spence, I had been influenced by people at the record companies like Electra Records and Vanguard Records, and working with them, I had gotten used to a certain placement for a microphone—about halfway between the voice and the guitar. So by the time I recorded him, it was a different balance. But the mic was fine, so it was all good.

That's a fascinating detail. You know, there's one Joseph Spence song that immediately springs into my head. I have a big, curated playlist of music that I enjoy listening to over the Christmas holidays with the family. It’s a very specialized list as I find much holiday music insufferable. But in there is Joseph Spence's version of "Santa Claus is Coming to Town." I don't know when that was recorded his career, but it never ceases to amaze me the way he plays with pronunciation. I can make out the words to the songs on Encore more easily than I can on that song. He is just so out there with his distortions and slurs and vocables. Do you have any comment on how that approach came about?

It's just part of who he was. I think at times his guitar playing and his vocalizing, whether he's really singing or not, it all comes out of a Bahamian tradition called rhyming. It was a form of music that the sponge fishermen in the Bahamas used to keep themselves entertained by singing together when they were out on their sponging boats. They used to go out for weeks at a time. And if you want to know what rhyming sounds like, if you listen to the song on here called “Out on the Rolling Sea,” Joseph Spence is pretty much rhyming. Even his guitar parts are also in a sense mimicking the roles that the different singers in a rhyming group would play. He doesn't do an alternating bass like many finger pickers do. He basically reproduces the notes that a bass singer would've sung in rhymes with the treble and lead voices.

Rhyming. I've heard of this. But I don't know much about it. It sounds like there's improvising involved, almost like freestyling. But then there's also all this harmony too, and clearly set parts.

It's wonderful music. I have heard it live. It really isn't practiced anymore. It’s pretty much faded away. There was a lead singer, if you will, called the rhymer. And there were bass and what they call treble singers. People would call it tenor singers today. There were three parts and there might've been additional people singing too. It was a form of harmony singing with the lead and the bass and the treble. But the rhymer, the lead singer, would extemporize, and go off on these wild adventures of—almost like rapping—very highly syncopated improvisatory quick singing, and it had something in common with the way calypso was used in Trinidad, because it was like a sung newspaper also. They would sing stories about drownings and storms, and also Bible stories. So they got really very complex.

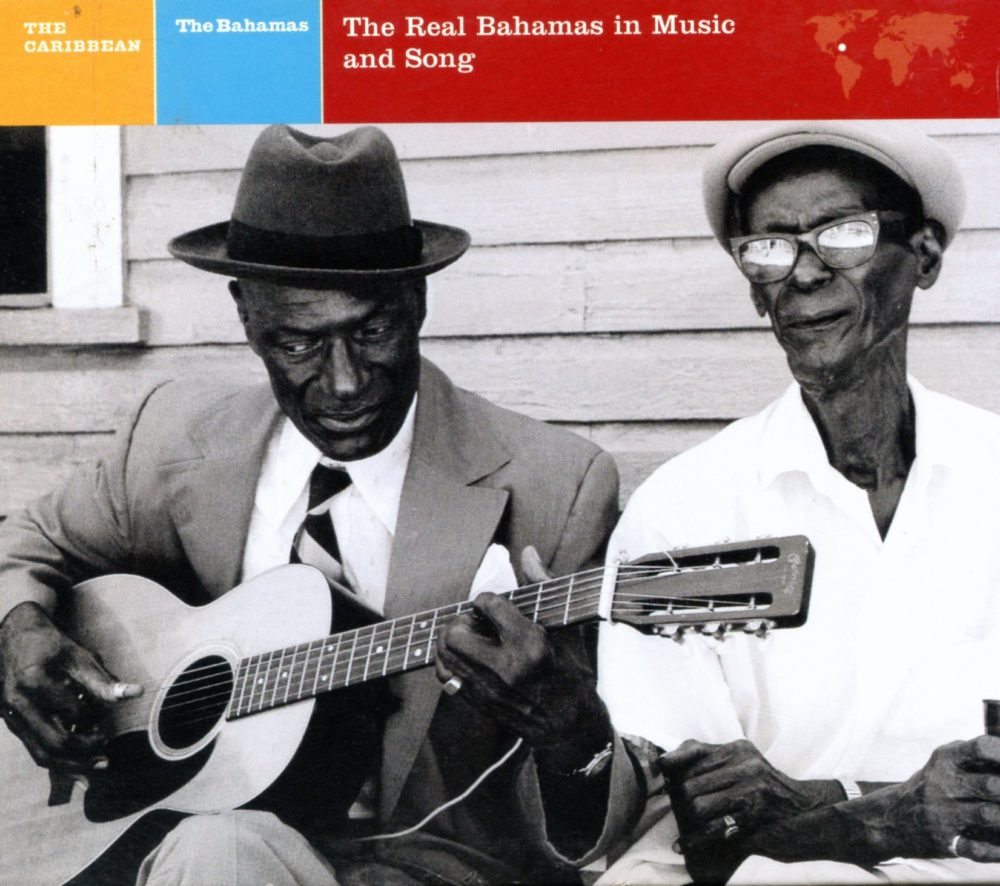

If you want to hear some great examples of rhyming, there are a few albums. There is one that Sam Charters produced that is volume two of the Folkways International Series, Music of the Bahamas. And Jody Stecher and I put out two records called The Real Bahamas, Volumes 1 and 2, on Nonesuch Records.

I believe all that stuff was reissued on CDs a few years back. I will have to go back and listen with fresh ears.

Where are you, by the way?

In Middletown, Connecticut, not far from Wesleyan University, where our radio program was born.

Ah, Wesleyan. Did you know Robert Brown?

Yes. Not personally. But he was a founder of Wesleyan’s ethnomusicology program. Something of a legend.

He was an old friend. When I finally went to work at the record company, at Electra Records, I started a label called the Nonesuch Explorer Series.

Of course.

And Bob Brown introduced me to a number of South Indian, Carnatic, musicians who I recorded for that label, so I got to know him very well.

Yes. The South Indian music thing was huge at Wesleyan. And I no doubt listened to those albums you recorded. We were lucky enough to study with some of the great musicians Bob brought in, Viswanathan and his brother Ranganathan. Amazing artists. Wonderful teachers who put on fantastic concerts. Also just great people.

Sure. I recorded all those guys. Those Carnatic albums were actually the first to come out on the new Nonesuch Explorer series.

What year did that label start?

Well, Nonesuch Records was a label that Jac Holzman started as a subsidiary of Electra. It started as a classical music label, licensing very high quality records from companies in Europe and put them out for a reasonable price. You could adorn them with fancy drawings. At that time, he also started something called Nonesuch International series. At that time, there was a genre of records called "international.” It was not as culturally specific as the records we did later. For example, there was a record called Bouzouki, The Music of Greece. That kind of thing. Steel Drums, The Music of Trinidad. They were licensed from the same European companies. But when I got to Elektra I, together with Teresa Sterne, who was the director of Nonesuch, decided to turn this into a real label. We began recording musicians, making a serious effort to record serious musicians with serious sleeve notes—high-quality recordings. That was the Nonesuch Explorer series, and I believe we made the change in 1967.

So by the time I got to Wesleyan in 1975, you had a number of releases out there. I used to take them out of the Wesleyan music library and to dub them onto cassettes. That's how I first heard mbira music from Zimbabwe, from the recordings that Paul Berliner made for Nonesuch Explorer. For me, that was huge, since a lot of my work since then has involved that music.

The catalog numbers ran sequentially. From one to 10 I think was Nonesuch International. So the South Indian albums we did for the Explorer series were a continuation of the same catalog number series. But the Explorer releases looked and sounded very different. I left my job at Elektra in 1970 and became an independent producer. Then Tracy Sterne continued and did great work. I had met a guy named David Lewiston.

Sure. He did all that great recording in Bali.

Yes. We released his first records of Indonesian music. Gamelan records. And he continued on. The label continued to do a lot of work in Africa too.

Fantastic history. We all stand on your shoulders. And thanks so much for reintroducing us to Joseph Spence. This is a terrific release.

Thank you so much. It's been a pleasure.

Related Audio Programs