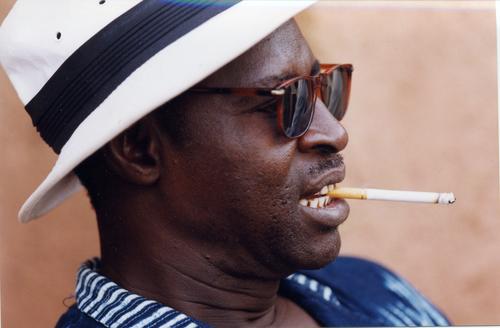

Hama Sankare was known throughout the world for his calabash percussion, accompanying the legendary multi-Grammy-winning, “King of the Desert Blues,” Ali Farka Toure.

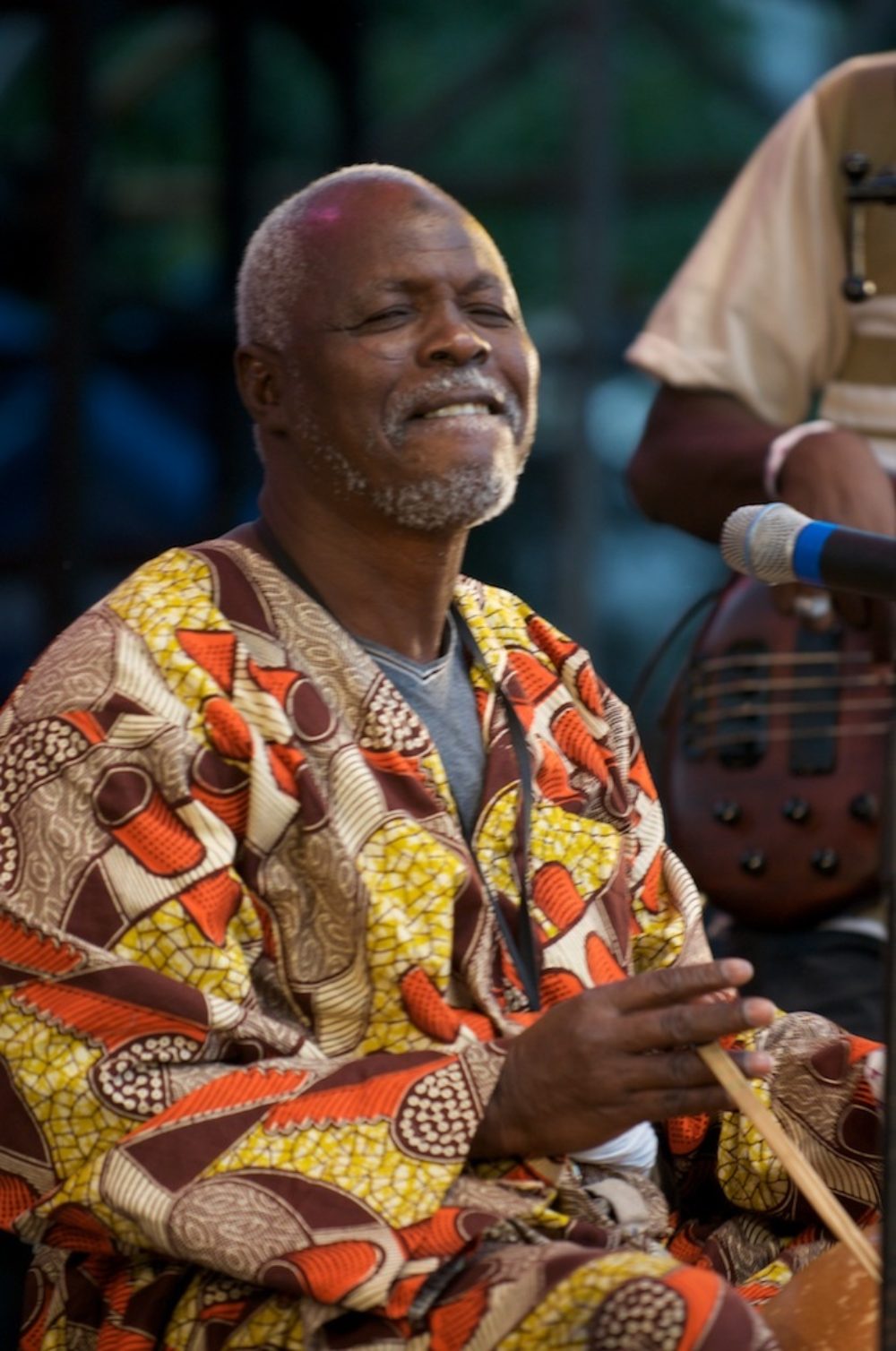

Traditionally the calabash was played by women in Northern Mali, who used the large, bowl-shaped gourds in the preparation and serving of food, then turned them upside down and played them like a drum, using the palm, the fist, and the fingers, sometimes with rings. Hama first heard and saw this being played by his aunt, and as his virtuosity evolved; he began using thin sticks to create the effect of two instruments playing at the same time. By the time Hama was performing with Ali Farka Toure on the grand stages of the world, with a microphone placed under the calabash to be amplified through thunderous sub-woofers, audiences marveled that so much sound was coming from one person, who was sitting inconspicuously on the floor and rocking the house with what looked like a large, upside-down wooden bowl.

Hama was born in Niafounke, Cercle du Tombouctou, in Northern Mali, in 1952, and went on to travel widely, performing with traditional as well as regionally popular artists. Along with adapting traditional music featuring songs about the agricultural life of the Sonrai, he also performed during the spirit ceremonies called Hole Hoira, an ancient tradition which pre-dated the arrival of Islam in Northern Africa. He was called back to Niafounke to provide the crucial rhythmic foundation for the music of Ali Farka Toure, to whom he was related by marriage on his mother’s side, and he went on to record and tour with Ali for 25-plus years.

During a time when the music of Mali was dominated by the diatonic, mellifluous sounds of the Mande kora, the minimalist, pentatonic, deep roots music of Northern Mali’s Sonrai (Songhai), Peul (Fulani), Bozo (river people), as well as other regional ethnic groups including the Tamashek (Tuareg), were marginalized - rarely played on national radio, and unknown to the outside world. Through the vision and efforts of British producer and label owner Nick Gold, Ali Farka Toure’s unique sound found rapturous audiences around the world, beyond the ghetto that confines most of what is considered “world music.” These early recordings were just acoustic guitar accompanied by calabash percussion, and many featured Hama singing en duo, often in unison with Ali. Eventually Ali’s style, combining his dazzling legato lines played finger-style on electric guitar, with the unique sound of the calabash found massive success in collaboration with American roots guitarist Ry Cooder on the Grammy-winning Talking Timbuktu album, released in 1994.

Hama was a stunning presence vocally, covering a wide range of notes and vocal tones, as can be heard in his recordings with his cousin, songwriter Afel Boucoum, and on his own recent albums produced by the American producer Chris Nolan, Ballébé and Niafunke. Hama also collaborated with international artists, including British superstar Damon Albarn (Blur, Gorillaz), and American blues-based singer/songwriter Markus James.

In Mali, musicians are awarded national prizes for being the best at their instrument, and Hama always received the prize for best calabash player, going back to 1968.

Hama was known far and wide for his upbeat, jovial, people-loving personality, and his powerful work ethic. In addition to his life in music, Hama worked consistently as a farmer and also repaired electronics.

He is survived by his wife Sumbu, and eight children.

From Markus James:

Hama was an unstoppable force. He exuded strength. If you were driving along in some vehicle, surrounded by endless miles of sand and chaparral, and something stopped the car, he was the one who would dig away the sand, climb under, figure it out and repair it, using next to no tools.

I had a song, about a horse thief, and when I told him the story his eyes grew wide and he said “This is our story called 'Jay Bere,' a true story of a horse thief here in Northern Mali.” We talked about making a video, so people could see what it looks like there in the region of Timbuktu. Hama took over completely, led us to the village of Toya along the banks of the Niger River, got the elders together in some shade and made a deal. The whole village would stop work for a day, and we would employ four horses and riders. It gets really hot there (125-plus degrees), and on the big day, mothers started trying to gather their kids to get into some shade, and all of us were seriously wilting. (The leather band on the inside of my hat literally melted.) But Hama was out in the center of the village, directing everyone, saying “Let’s do it again!”

I can think of a million stories about Hama. He was in touch with the jinn, the spirits; and this certainly permeated all aspects of his life.

When talking about our song “Gobissa Tamba / Things We’ll Never Understand,” which translates as “life is passing quickly.” Hama said something which now seems quite prescient: “You never know what is going to happen…a person goes out in the morning and they may never come back.”

Now that day has come. On March 29, Hama was on his way back to Bamako after casting his vote in Niafounke during parliamentary elections when the vehicle he was riding in hit an IED. Everyone aboard was killed. Hama’s insistence on voting was a strong gesture for the future of his beloved Mali; and though he will not be coming back, his voice, his calabash, and his life will resonate among his people and far beyond.

Related Audio Programs