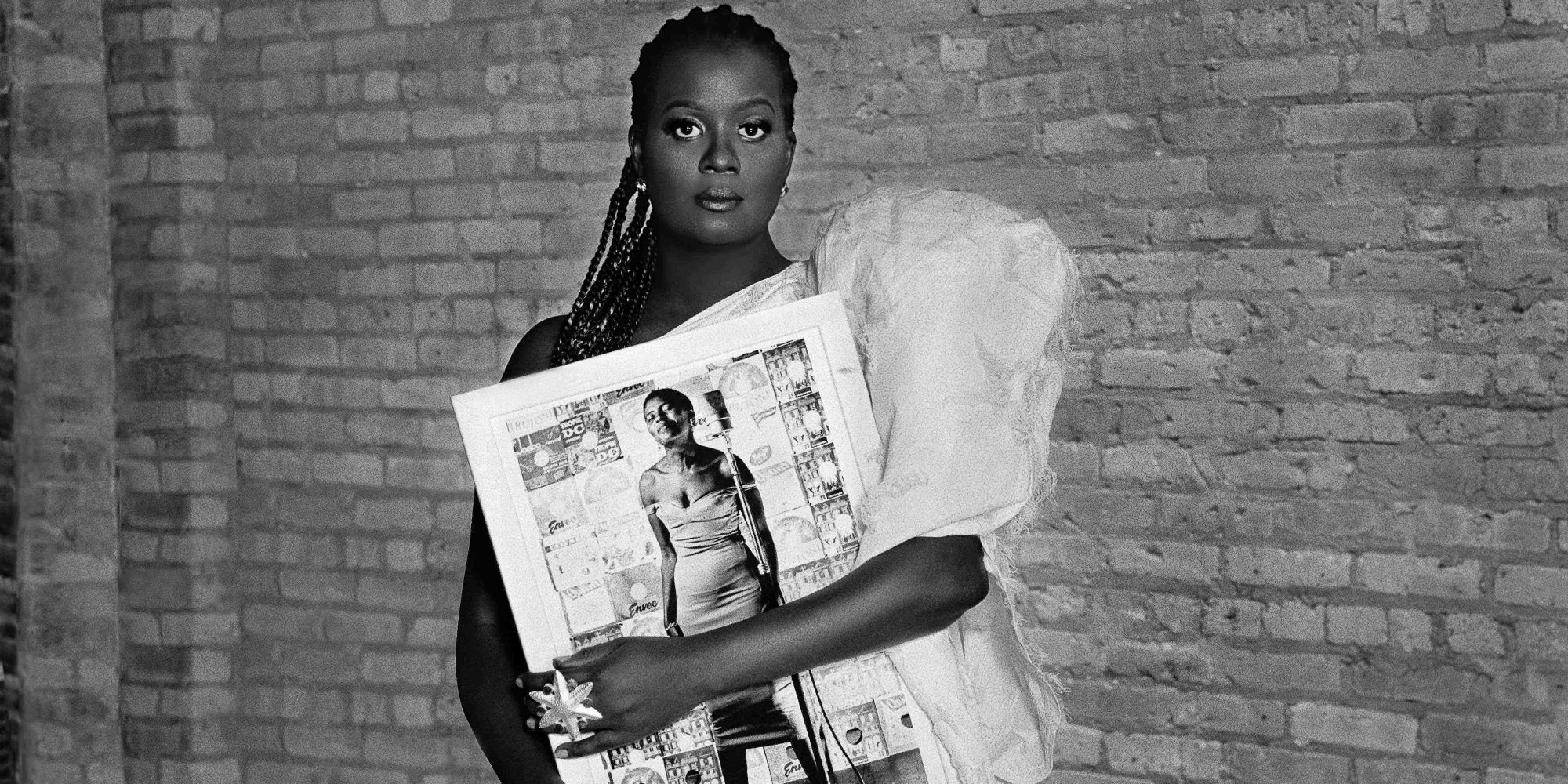

SOMI is a Grammy-nominated singer, a songwriter, composer, actor and a playwright who has shared the stage with some of our world’s biggest stars—Angelique Kidjo, Common and her longtime mentor, the legendary South African trumpeter Hugh Masekela. Of Rwandan and Ugandan descent, Somi was the first African woman nominated in any of the Grammy Jazz categories last year for her live album Holy Room- Live at Alte Oper.

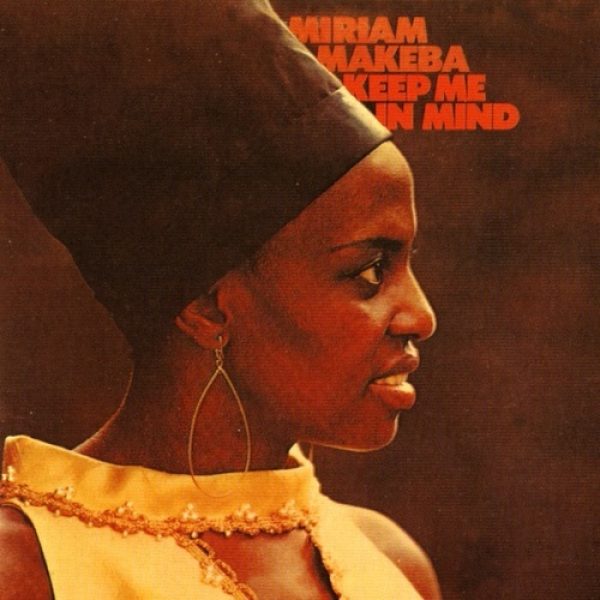

For the last seven years, Somi has been grappling with the legacy of Miriam Makeba. The South African singer/songwriter and anti-apartheid activist is an icon and legend across Africa and elsewhere. But despite spending time in America, being right in the center of the mid-20th century New York jazz and folk scene, Somi has been surprised at how many people in America either don’t know who Miriam Makeba is, or don’t know much about her. That may be changing.

On March 4, Somi is releasing her fifth studio album, Zenzile: The Reimagination of Miriam Makeba, on the heels of the Somi-penned play Dreaming Zenzile, an original musical theater production that is set on the night of Miriam Makeba’s final show, the last night of her storied life. Her presentation of the album will headline the Apollo Theater’s Africa Now! festival on March 19. The latest single from the album, “Khuluma” is out today.

While the play was being staged in Princeton, NJ, Somi took time from all of this to talk to Afropop’s Ben Richmond about the play and the album—whether she sings differently in the character of Miriam Makeba versus singing a Makeba song as herself, and why Makeba’s legacy is so tenuous in America.

Ben Richmond: First off, for our readers who might not be familiar with you yet, do you want to introduce yourself?

Somi: Sure. My name is Somi. Kakoma is my last name. I'm a vocalist, a writer, a composer and an actor.

And your play has already played in St. Louis?

Yeah, it started in St. Louis. We were originally supposed to open in March 2020. So five days before opening night the pandemic hit. Obviously we were shut down. Thankfully we returned to St. Louis for all the subsequent productions that have been planned. That started in August of last year. So we were there and opened in September. We are doing a rolling world premiere in regional theaters across the country and then we will land in New York for an off-Broadway run this summer.

That's very exciting. And the play is of course something that you wrote. Does that weigh on you or how does it feel?

I feel excited. To date, I'm mostly known as a vocalist and composer and songwriter. But theater is something I've always loved. So the opportunity to really stretch out artistically has been deeply challenging and deeply rewarding. It feels like my most holistic representation and or presentation of self, artistically and intellectually—and musically. It's been exciting for me as a writer, as a performer and as a vocalist. As a performer I never would have introduced myself as an actor but that is what is required of the piece, so that's been exciting to really lean into that. And as a writer it's been really thrilling to share that. I've always written things outside of songs but to share a larger work in this way artistically and publicly has been really thrilling. It also has an honor to get to stand in the story of Miriam Makeba and be able to try to hold her voice and legacy. I really try to honor her voice while honoring my own. It has been a deeply rigorous spiritual and artistic practice. And I'm grateful for it. In exploring her voice I discovered new things on my own. So I'm excited about that. I'm excited about this large-scale cultural memory project. Not only sharing her recorded music but also being able to share this multi-dimensional story through theater and ask people to journey with me for a while. I'm excited about all of that. But it's definitely a heavy lift.

Which came first, the idea for the album or the idea for the play?

I would say it was the album first. I would say I was interested in trying to figure out how to tell her story. So the first support I had around, seven years ago I applied for a grant through the Mid-Atlantic Arts Foundation. They have something called French American Jazz Exchange and I asked a longtime collaborator of mine, Hervé Samb, a guitarist/composer who is Senegalese but based in Paris whom I have worked with for many years, if he would like to collaborate with me on this. The grant application was to reimagine Miriam Makeba's music. I was really just interested in having time to understand her story, and take a deeper look at her story and life's journey, and hopefully get some insight into what her music was about. I think we all have broad stroke understandings of what she was about. That's something I realized, that as someone who thinks I know a lot about Miriam Makeba, I really only know the surface. I didn't know as much as I thought I knew. I think everyone can speak to her opposition to apartheid, her activism and what she represented culturally and so many of the first that she was able to do and be as an African artist and woman.

But I realized when I really started researching her story, reading her autobiography, translating the lyrics of her whole 50- 60-year catalog of music, talking to her colleagues and people who were close to her, I realized how much we didn't know. In many ways I was just committed to honoring her story and her life. I wasn't sure it was going to show up as a play. But the initial thing was to let me reimagine her music. And the more I learned the more I wanted to tell. That's when I realized that honestly the dimensionality of an album wasn't large enough for her life story. So these two projects are really meant to be in conversation with each other. The album as myself honoring her as a vocalist; and the play asks people to believe they're there on the night of her last performance, which was also the final night of her life. And stepping into memory with Miriam Makeba.

Do you sing differently on stage as Miriam Makeba, as opposed to on the album, where you sing a song either popularized or written by Miriam Makeba?

That's a wonderful question. I make different musical choices absolutely on stage in character. But I think some of those choices were just because of the blurring of the mind, and also at this point after a seven-year deep dive, with multiple years of research and study, I already had a closeness to the material from the workshopping of the theatrical side of things. But I tried to be intentional. For example the song, "Milele," which on the album also features Seun Kuti and Thandiswa Mazwai, that leans into a lot of African pop tendencies with the arrangements and the choices that were made there. That is not what it is in the play. In the play it leans more towards her time in Guinea. The other thing is that in the play there are spirits that are showing up and performing so it's not just my voice if you will. So the answer is yes and no. At times yes and at times definitely no. And even if the song shows up in both places--and not all of them do but there is some overlap, about half of the album-- that has to do with my love of those particular songs and also not being able to choose which one to let go of. But in many ways that has been the journey for the album. The journey is trying to figure out how to honor her voice but still honor my own. I'd like to believe that something new has emerged. In that meeting of voices a new voice has emerged. I'll leave it at that.

That makes sense, it seems like there would always be lots of gradations—she could have been an influence on you your whole career.

I don't think any African musician, any African creative, particularly an African performer or African female vocalist, could say they were not influenced by Miriam Makeba in some way. Because the reality is in some ways she was the original spacemaker. I'm here and I'm able to be articulating in transnational ways because Miriam Makeba was the first to do that. She was really the first African artist to show up on the global cultural stage. In recognizing that we are all indebted to her. So this is an homage to her own work and her voice and legacy. And that homage is in many ways a letter of gratitude. So influenced, absolutely. And indebted to more so than anything.

I'm curious: As you've gone around promoting these projects, have people in America heard of Miriam Makeba? Do they know "Pata Pata" or what would you say our general knowledge level is?

I realize that I cannot anticipate the person who is going to know who she is. I used to be like, “Oh of course this person will know who she is” or “of course that person will know.” And it's not about generation, it's not about race, it's not about culture, it's not about musical taste— it's wildly variable. And it used to surprise me a lot and sometimes disappoint me, and sometimes frustrate me. Now I think it just speaks to a certain type of erasure. To me she was as big as she was and more people don't know or remember her. People might know the song “Pata Pata” but they don't know who sings it or you may have to jog their memory and they'll say they remember the song. Or that's the only song they know. Or they've heard the name and don't really know why they've heard the name. It points to a very sudden and violent cultural erasure. That sustained cultural erasure from when she married Stokely Carmichael at the height of her career, and the blacklisting that she then experienced. Everyone abandoned her: her recording contract, her record label, her manager.

She moved to West Africa because she was exiled from the cultural association because of her marriage to Stokely Carmichael. It really sustained itself. It wasn't really until the 1980s when she was quote/unquote reintroduced to the American public through Paul Simon's Graceland tour. At that point it had been 20 some years and she had mostly been touring in Africa and Europe and some parts of Latin America. It's very interesting to me. To me it's a great failing that she wasn't honored in a bigger way. In the later part of her life of course people would honor her as Miriam Makeba but I just feel like she hasn't been remembered. This is someone who is moving in the upper echelons of society in this country. Her best friend was Nina Simone; she was married to Stokely and Hugh Masekela; she performed at JFK's infamous birthday party just before Marilyn Monroe. She was very close to Marlon Brando. You think about who was in the room when Harry Belafonte introduced her at the Village Vanguard--Amiri Baraka, Duke Ellington. And all of this constellation of folks. Not tangentially or peripherally but in that world and really a part of it. So to me this is my small effort to ask people to remember and honor her in the way that she really should be. So I'm always surprised when people don't know who she was, as someone who can't remember not knowing who she was. I think most Africans of my generation grow up hearing Miriam Makeba's music. You grow up knowing who she was.

I think I came across her just through record hunting but it wasn't until I came across a recent reissue that I learned that she was there in the Village. She does covers of songs like "Proud Mary" as an international pop artist.

Or when she covers "House of the Rising Sun,” those are the choices she was making, singing songs from here and also from how. How much of that was because she wanted to make those choices or because she had to or someone pressured her, or it's what she felt she had to do to be relevant, I don't know. But in addition to singing songs from America she would go and find songs from Indonesia, from Cuba, songs from Kenya. I think that's just who she was. There's a record of hers, The Guinea Years, that is so beautiful. It's mostly live. And she's mostly singing traditional songs from there or reframing and rephrasing some of her original South African music and placing it in a West African musical context. It's really an amazing pan-African statement.

Just as we can acknowledge the American music she decided to cover, you can also point to that influence. A song like "Pata Pata," I believe the Supremes covered it, I believe Cher covered it—at the height of their careers, which spoke to the influence of Miriam Makeba. And I'm not saying those are good covers, but I really just point to that to say there was this exchange and sharing. At that time, genres weren't as big; things were a bit more fluid so people were showing up in places. And language, maybe it put you in a folk space but it didn't immediately remove you from a pop space. That's been interesting to reflect on, that bidirectional exchange of popular and African styles, in her own repertoire and in those of her contemporaries.

We should talk about the single, "Khaluma," which features the artist Msaki. Can you introduce it to listeners?

"Khaluma" is a song I love love love from Miriam Makeba. It's from an earlier recording."Khaluma" means "speak." That song, like many of her songs, and that were recorded at the time, and it speaks about the condition of Black South African life. A woman goes to a bar and she's asking her husband to come home and about the kids that are sleeping and she doesn't want him to wake them. The literal translation doesn't really do justice to Black South African life that she's speaking about and asking people to consider. So I chose it for what it meant in that era of apartheid, but also because I loved it. I loved it before I knew what it meant. I invited Msaki, who's a wonderful young South African singer and songwriter based in Johannesburg whose work I love and voice I love and it was really important to me to invite guests, mostly South African guests but people from across the continent to honor Miriam and her legacy as being a proud pan-Africanist.

The play is opening in June in New York, but do you have plans to tour as a musician for the Miriam Makeba album?

Yeah! In March I'm going to be in Johannesburg, travel logistics permitting, but my plan is to be in South Africa for the release there, with my guests and the audience that has supported me for a long time. Obviously in her home country. And also I'll come back March 19, I'll be doing a show at the Apollo with various guests from the album as well. I'm so excited it's my first show on their main stage. That will be honoring her and celebrating her music with New York City, where I've called home for so many years. So I'm excited. And then touring in the summer after the play's run.