Ryan Skinner is an ethnomusicologist best known to Afropop listeners for his work on our programs about the Mande diaspora in New York City. He is currently working on a book about, of all things, African music in Sweden. Ryan reached out to us last year encouraging us to create a program on the subject. To be honest, there was some skepticism and good deal of surprise from the Afropop team, but boy, were we rewarded by our faith in Ryan. He came through with a fantastic story, and introduced us to a wonderful talent pool of artists in Sweden, with fascinating, moving and provocative stories. The resulting program "A Visit to Afro-Sweden," is sure to be an Afropop classic. In preparing for the show, Banning Eyre spoke with Ryan. Here is their conversation.

Banning Eyre: First, Ryan, reintroduce yourself to our audience, and tell us how you ended up focusing on Sweden.

Ryan Skinner: My name is Ryan Skinner. I'm an ethnomusicologist, an anthropologist, and associate professor at Ohio State University. Put simply, I married into Swedish culture. It’s been part of my life for the past 20 years. My kids are Swedish-American. My family and I spend time in Sweden every year. Fifteen years ago, I lived and worked in Sweden. I had a job as a middle school teacher, teaching English and French. The school where I taught was introduced to me as “an immigrant school.” So, I became very quickly aware of dynamics around race and ethnicity in Sweden. At the same time, I had recently returned from Mali, following a period of field work in that West African country, and I quickly became involved in the local West African associations and communities in Stockholm. I got to know the Malians, the Gambians, and the Senegalese very quickly, and I also got to know some of the musicians, and collaborated with some of them. So, early on I was roped into an African music scene in Stockholm, as a kora player, but also as someone working to bring that music to local scenes and stages.

Working as closely as I did with African communities in Stockholm, I noticed very clearly the ways in which Africans and African music were being modeled as exotic and foreign to Swedish society. That is, African musicians living in Sweden were living and performing as “Africans”—as exponents of a foreign music culture—not as local Swedish artists. From a certain point of view, that was understandable. There was great interest in world music at the time in Sweden, and in African music in particular. But it was also quite strange, because these artists were residents of Sweden, not foreigners! So one of the things I did was to collaborate on an event, called the Jalibengo Kora Festival, which was held at Stallet, Stockholm’s preeminent venue for folk music and dance, in 2003.

It was a festival of kora players, the majority of whom were living and working in Sweden. The idea was to present these folks as local Swedish folk musicians, and make the case that they also have a right to occupy and perform on those stages, alongside Swedish musicians. There’s an apt phrase in Swedish that describes what we were trying to do, ta plats, to take or claim a place. Artists were beginning to occupy those spaces and perform in ways that suggested that they belong here, and were going to stay there.

Speaking of the kora, you introduced us to an act with a very contemporary story. Sousou and Maher Cissoko are a husband-wife duo that traces back to when a young Swedish girl, Sousou, became fascinated by the kora and began going to Gambia and Senegal to study. Long story short, she ended up falling in love, and now Sousou and Maher have a remarkable international career.

I’ve had many opportunities to interact and collaborate with Sousou and Maher over the years. In fact, my first encounter with Sousou was in 2003 during the Jalibengo Kora Festival! It’s a long story, but after our main act fell through, I had to run a kora workshop at the last minute, and some of the instruments were not holding their tune. I knew she had been to the Gambia and studied kora, so I asked her to fill in for me while I tuned up the instruments. Already, she had all the makings of a fine player and was very kind to me help out in a tight spot!

In 2014, Sousou and Maher actually came to visit us at Ohio State, giving a live performance on campus, running a workshop with our own kora ensemble in the School of Music, and joining a public discussion on music, culture, and race in contemporary Sweden. It was fantastic! My students and colleagues still remember their time with us fondly.

Eight months later, I joined Sousou and Maher in their other home, Senegal. I spent a week documenting their busy performance and promotional work in the country—from their fatigued arrival at the Sobo Badè cultural center just before a scheduled concert (the group was delayed by a failed coup attempt in neighboring Gambia) to their prime time performance on the Night Show (a flashy variety show program on Youssou Ndour’s influential TFM network). Staying in a guest room in their Dakar apartment, I also got a glimpse of Sousou and Maher’s everyday life, in which, beyond their identities as professional performing artists, they are also mother and father, daughter and son, friend and relative, and much more. At home, we discussed their dreams, anxieties and desires; of laying the groundwork for a more permanent residency in Senegal; of their anger and frustration with an everyday and deeply entrenched racism in Sweden; of their love for travel, seeing new places, learning from cultural difference, and, always, expanding what it means to make music together—the guiding sentiment of their new album. Our week together felt more like a month, or even a year. I relish the time shared with Sousou and Maher, their friends and family, in Senegal, and look forward to the next moment our paths cross.

You mentioned to me that as you spent time in Sweden, you began to notice changes in the African music community there. What did you notice?

I began noticing that there was a need to rethink the presence, culture, and art of these African musicians in Sweden. Ten to 15 years later, the conversation was no longer about “African” communities and Swedish society. Rather, we were confronted by a new generation—the children of some of those artists I worked with, and the middle school kids I taught, now adults themselves—they were beginning to say: “This dichotomy of us and them, Africans and Swedes, it doesn’t make sense to us. My mother is Swedish and my father's African, or vice versa. I belong to both places. I am Afro-Swedish.” By 2010, there was the makings of new language being spoken by a new generation about what it means to be black, African and Swedish.

As we know, there are African communities in many European countries. Obviously, we have focused a lot on those in France, England and Portugal. But we know there are also African musicians living in places like Denmark and Norway. But you argue that Sweden is different. So my question is, why Sweden?

Why Sweden? To speak of Afro-Swedish history, we really have to talk about two moments. The first takes us back to the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, when Sweden was an active participant in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. They built Cape Coast Castle in Ghana. They occupied St. Bartholomew in the Caribbean. So there has been a small African presence in Sweden going back 200 or 300 years. That is one Afro-Swedish history, and it leaves a trace. There is an exhibit at the Ethnographic Museum in Stockholm that traces this deeper history right now!

To talk about a more recent Afro-diaspora community, however, we need to talk about another moment of history, and that begins in the mid-20th century when we have waves of groups coming from the African world, different parts of it, the Caribbean, the Americas, for different reasons. Some seeking refuge and asylum, others simply seeking a better life. And for a long time, Sweden is accommodating these groups with rather generous immigration policies.

This community goes back about 60 years. If you look at Scandinavia as a whole, the population of Afro-Swedes—that is, Swedes with some kind of African or diasporic background—it is far greater than what you find in neighboring countries. Yes, there are African communities in Norway and Denmark and Finland, but they are not nearly the same in terms of scale and size. And that has a lot to do with the more generous politics of immigration, refuge and asylum in Sweden, historically. Denmark has long pushed for strong border restrictions for non-EU migrants. Norway has also seen more foreclosed immigration in recent years, as has Finland. So yes, there are African and diasporic populations in all those places, but they are much larger and now several generations old in Sweden, so that definitely sets the country apart. In fact, given the Afro-Swedish community’s size, scale, and population distribution (urban segregation is a real issue in Sweden), it makes more sense to compare Sweden to countries like England and France, than to its other Scandinavian neighbors.

Let's talk about some of the other artists you've introduced us to, starting with the oldest one.

Richard Sseruagi is a musician and actor who fled the brutality of Idi Amin's Uganda in the late 1970s. There were a number of groups that came from different parts of Africa in the wake of the colonial period. During the postcolonial years, some of these people, like Richard, were fleeing strife and struggle in their home countries. In Richard’s case, he finds a safe haven in Sweden, where he has been able practice his art as an actor and musician.

Richard seemed quite happy to be living in Sweden, but he noted that it hasn't been easy. He was quite upfront and saying that racism prevents African professionals who from reaching their potential. He spoke about doctors and lawyers working as taxi drivers and janitors.

So, here is a really important point. The people who came to Sweden and sought refuge and asylum, did find those things. However, the stories people heard about Sweden as a place without race, or that racism didn't exist in Sweden at all: These folks arrived and discovered that this story wasn't true. It was a myth.

Richard's music is buoyant and lovely, rather like old-school Afropop. I particularly enjoy his song “Say Say Say.” And I think there's a story behind that song, isn't there?

The song “Say, Say, Say” appears in the film Medan Vi Lever (While We Live), which is filmmaker Dani Kouyate’s first feature film in Sweden. (He’s got five major films to his name.) Dani is a native of Burkina Faso, but now lives in Uppsala. He cast the role of Sekou, a taxi driver and endearing uncle, specifically for Richard Sseruwagi. At a crucial moment in the film, Sekou is riding with his nephew in his cab with a white middle-aged man in the back, and this man is clearly perturbed, even disgruntled, to be in a cab with two black people. Uncle Sekou diffuses the situation by playing this track on a cassette deck in his cab, “Say Say Say.” [The song encourages people to enjoy day-to-day life, despite the problems they face.] When they get out of that cab, and everyone's feeling happy about themselves.

Very nice. All the artists in this program have distinctly different narratives. But maybe the most significant ones are those who were born in Sweden, but with African ancestry. Tell us about these second-generation Afro-Swedes.

What is important about this current moment is that the discourse, the music, the culture, is being driven by a new generation of Swedes, as you say, of African descent, who identify themselves as both Swedish and African—both Swedish and black. They are embracing terms like “Afro-Swedish” (afrosvensk) and “African-Swedish” (afrikansvensk) to talk about and socially position themselves. So this current moment is being driven by their voices and their art. The singer Seinabo Sey is a prominent exponent of this moment and these people.

Right. Her father comes from Senegal and Gambia, and her mother is Swedish. So she's born in Sweden but with an African identity. Tell us more about her.

Seinabo Sey breaks out onto the Swedish scene in 2014, winning awards for best new artist. The following year, she wins an award for the best soul and r&b artist. She is flooded with accolades on the Swedish scene. By 2015 and 2016, that begins to spill over into the United States, with write-ups in the New York Times. You can go into a Starbucks today and hear Seinabo Sey on the radio.

Seinabo Sey’s music is strongly rooted in soul. And soul has a very deep root in Sweden. It's been one of the most popular genres of popular music since the 1980s. This period was also formative for the current generation of Afro-Swedes, and Seinabo is part of that. In this generation, there are more people of mixed heritage, with strong ties to both Africa and Sweden. It's a growing community, currently empowered in various ways to speak out—against injustice, discrimination, and racism. But really, what Seinabo would rather be doing is making beautiful music, conveying the emotional depth of the spirit—the soul—that she brings to her sound.

Yes. She mentions that in her interview. She very much does not want to present herself as a political voice, and though she has strong feelings about the situation for Africans in Sweden, she doesn't want that to define her art. As you say, she's a singer of emotion. But I understand that she did orchestrate a rather powerful public statement recently. Tell us about that.

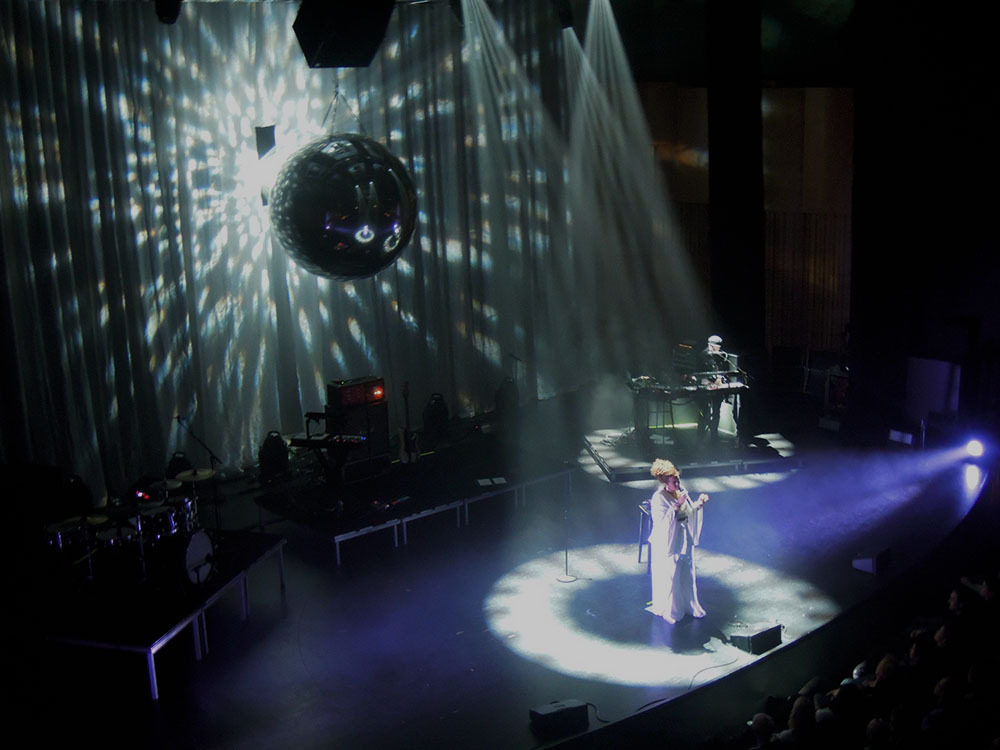

That's right. So, her sound is solidly pop music: love songs, break-up song, dance songs, tracks you hear at the club. But Seinabo is also very conscious of her identity as a black woman in Sweden. That comes out implicitly in her lyrics and music, but explicitly in the way she represents herself visually, in her music videos and on stage. For example, at the 2016 Grammy awards in Sweden, Seinabo takes home the award for best pop artist. She then takes the stage for a live performance on national television. The track "Hard Time" starts. Gradually, women from offstage begin to populate the stage, enter into the audience, fill up the auditorium. They are all black. They are all women roughly in Seinabo’s generation, and they are standing stoic, looking straight ahead, as if to say: We are black women. We are here. We are part of Sweden. We are proud. We are beautiful. And we’re going to make a statement

It’s interesting, because Seinabo’s statement comes in the wake of Beyonce’s “Formation” performance at the Super Bowl that same year. Now, Seinabo has been very explicit in saying that her performance had nothing to do with Beyoncé’s, but it is suggestive of a moment, a transnational moment, a global black feminist consciousness.

What about the song Seinabo sang in that performance? "Hard Time.”

“Hard Time” is interesting, because it is one of the songs that she wrote about emotions, the kind of stuff that just about anyone can relate to. The song is about the struggle of just living, getting through and getting by. But then, on stage, she couples that with a statement that she really doesn't want to have to make but feels is currently necessary to make. And so when she brings out 130 black women onstage on national television, she is combining politics with music that is not supposed to be about politics but, given the way thing are, is going to be political nonetheless. She is saying that these black women are part of this Swedish society, and she is providing a platform and a stage for them by virtue of the success that her music has provided.

“Hard Time” is one of these really great pop songs that appeals to everyone, and the kind of politics that Seinabo, like so many others, must now grapple with.

Yes. I sense that ambivalence in her interview.

Ambivalent is the word.

Let's talk about Stevie Nii Adu Mensah, who goes by the stage name Mensahighlife. Both of his parents are Ghanaian, but he too was born in Sweden. Tell us about him.

Stevie's a great musician, but it's important to say that he’s also a producer. And in that sense, it is important to make the connection to Sweden as a place that has produced, over a long period of time now, great producers of popular music. (including songwriters like ABBA’s Björn and Benny, to more recent hitmakers like Max Martin and Ludwig Göransson, of Black Panther fame.) And so I think he belongs to that community of Swedish producers, cultivating the sound and making tracks for musicians. He's worked with Seinabo Sey, among other artists. Working as a producer, he also became aware of a need to instruct, train, and teach other musicians about production, songwriting, and performance. So he's connected his career as a musician and producer to a parallel career as a music teacher, in Sweden and Ghana.

I have the impression that his coming-of-age was somewhat rougher than Richard’s or Seinabo’s.

Stevie grew up in Sweden in the 1980s and '90s when a particularly violent form of racism appears. You have neo-Nazis patrolling the streets and targeting people who are not white. His family was a victim of far-right aggression. He is formed by that history of violence in Sweden. It's not something he can separate his Swedish experience from.

And this certainly comes out in his own music.

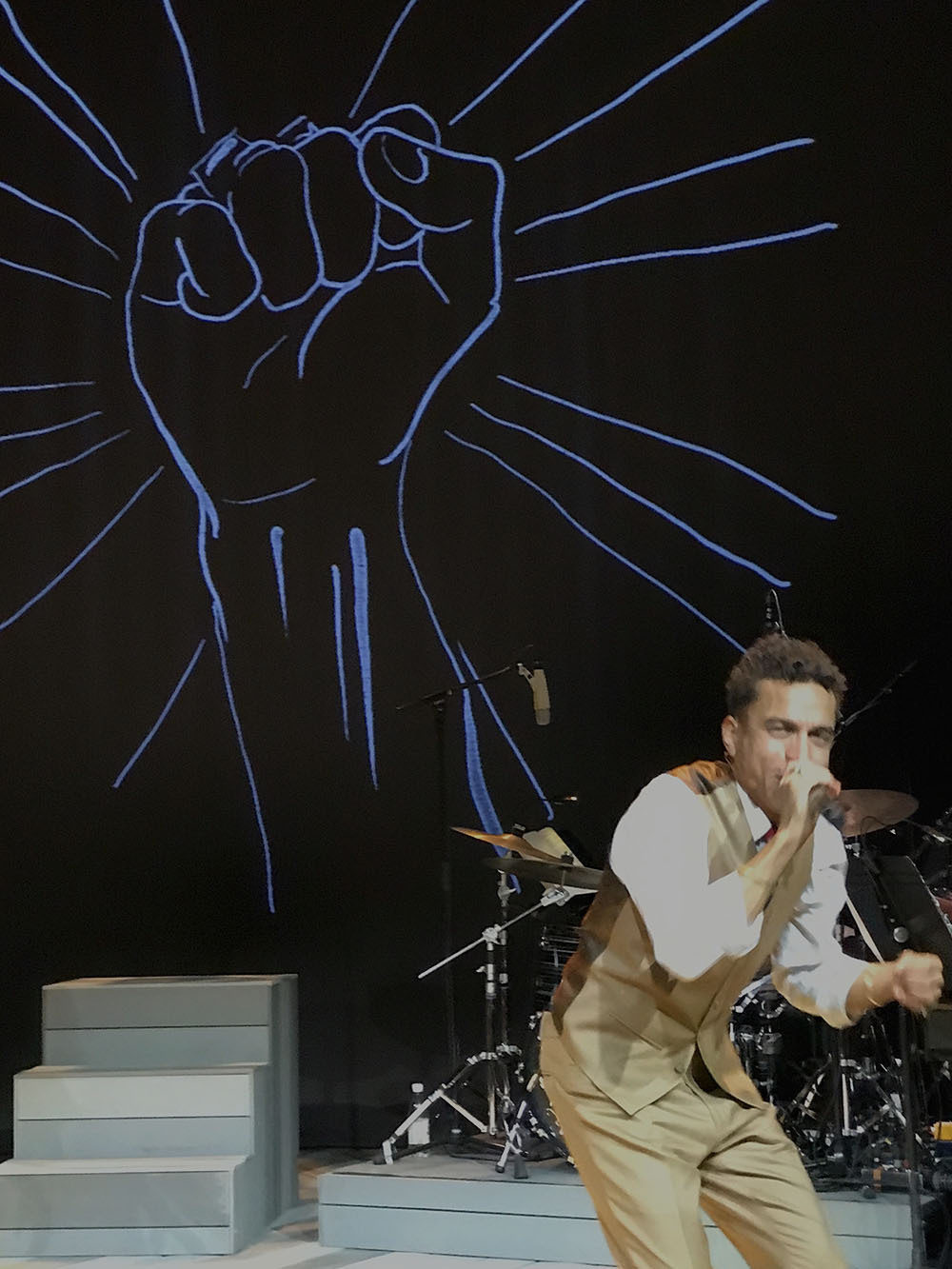

Stevie is deeply invested in a number of different musical genres. One of those is hip-hop. He grew up with hip-hop as a kid. He learned to breakdance. He learned to rap in the 1980s and '90s in the schoolyard, and watching MTV and films like “Beat Street.” “Du Blöder,” meaning “You Are Bleeding,” is a hip-hop track through and through.

Yes. He explains that the song was inspired when he visited his brother in a hospital after his brother had been attacked by skinheads. He saw that his brother was bleeding, and that gave him the idea for this song. So he's coming out of a tough experience of being black in Sweden. But I'm interested in how he responded to your idea that there's a kind of Afro-Swedish renaissance going on.

Yes, I proposed the idea that perhaps things may be in the process of changing. Over the past five to 10 years, we have seen a florescence of Afro-Swedish public culture in music, theater, film, and dance. And that we might be experiencing something we could call an “Afro-Swedish renaissance.” This is how he responded:

I agree with you that in around 2013, 2014, something happened when it came to embracing those African roots in Sweden. Because growing up in the '80s, none of that was around. I remember myself, because my situation was quite different because my father came in the '50s, but most people came from countries like Ghana, Uganda, Eritrea, they came in like the '70s, the '80s. And their goal was to learn the language quite quickly and become a part of Sweden. My parents’ situation was different, because my father, he was a respected drummer in Ghana. And his drumming and dancing and theater groups, they were serious. Wherever he went, he went with that state of mind. And my mom came here in the '70s, she was the same. She was dancing all kinds of Ghanaian dances, showing the rich culture that Ghana has. That was something she was very proud to showcase in Sweden, in the ‘70s traveling around and inspiring people, and getting people to try dancing these dances. And, you know, other African households that I went to, they didn’t really have that.

This background is very interesting. It seems like Stevie has a much stronger connection to African culture that a lot of Afro-Swedes who were born in Sweden.

That’s true, but when Stevie was growing up, hip-hop was also coming of age in Sweden. Not just hip-hop, but r&b too, and, as I mentioned, soul was already there. A lot of these reference points are coming from an American, and more specifically African-American context. These are the sources and resources people like Stevie are drawing on to express their sense of being black in Sweden, as part of a diaspora that includes hip-hop. By the mid-'90s, we begin to see rap that is in Swedish. A bit later, we begin to see new kinds of fusions, including popular music that's been infused by music from the African continent. And this changes the mix. Now the reference points are homegrown, and that has a powerful effect on the nature of music making and identity formation in the present.

Right. He says that African beats are now very common in urban Swedish music and that terms like Afro-trap, Afro-soul, Afro-dance, Afro hip-hop, are commonly used. So that represents real change. You mentioned though that Stevie is also an educator, and I'd like you to talk about one particular project that grows out of the song “It’s Cold Oo.”

“It’s Cold Oo” is a constellation of productions. It begins as a song. And the song is a narrative about two kids. It tells the story of bullying. It tells the story of climate change, and it is the soundtrack to another project, which is a book that deepens the story of these two children in Ghana. It's also a program that he brings to schools in Ghana, and now to Sweden, and so he's coming with his music and his narrative to talk about bullying, and to talk about cultural and racial difference in these two contexts.

Very interesting. Fascinating artist in person. Let's move on to Jason Diakite, who performs under the stage name Timbuktu. Here is how he introduced himself:

I am 43 years old. I am born in Sweden. My mom is a white American woman, and my dad is an African-American. My dad came and ‘68, my mom in ‘69. So I was raised in a home that was more or less an American home, and African-American home, a white American home, but of course the town and the country I grew up in was Sweden. My dad has strong ties to Nigeria. He spent six years there as a boy. There were a lot of Nigerians, then also people from Tunisia, Algeria, from the Congo, South Africa, Senegal, the Caribbean, Trinidad, India, and of course, African-Americans. And so I grew up, when I was at my father’s, hearing those conversations, and those perspectives on politics and world events, but also on being black in Sweden. They would often turn to me at points in the conversation and say, “Well, Jason, you’re Swedish. What do you think about this? ” And I always felt kind of singled out and not belonging at that point, because I was the one Swedish representative. One kind of significant thing about my dad’s home is that there were rarely Swedish people there.

There is a lot more to say about Jason, a fascinating person and artist, and I encourage people to check out his very diverse videos on YouTube.

You have to know that Jason is beloved in Sweden, by almost everybody. As Jason says, this moment is turbulent and fraught with peril, but that people like him genuinely give one a sense of hope. So I think that Jason is definitely a person who, like Seinabo, like all of these guys, are beacons.

Beacons in a time where things are becoming more difficult. Jason makes the comment that Sweden had so little role in the Afro-Atlantic slave trade that there are less wounds that need to be healed as opposed to other countries. At the same time, he and others are quick to puncture the myth that there's no such thing as racism in Sweden. Talk a little bit about how Sweden's politics have been changing in recent years, and not for the good as far as the Afro-Swedish community is concerned.

The reality is that while Sweden did not play as significant a role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade or colonialism on the African continent, it was not entirely absent from these practices and processes. And in those moments, Sweden was also receptive to the rhetoric about whiteness and blackness, about racial difference and hierarchy. Linneas, the famed Swedish botanist, help invent such ideas! And for several decades in the 20th century, Sweden was a pioneer of race biology, with a state-sponsored institute in Uppsala! So, over the past two decades, a number of skeletons have started come out of the Swedish closet, among them, more open and politically active far-right groups, with roots in fascism and racist ideologies. This has really flourished with the rise of a political party called the Sweden Democrats, with policies that are predicated on ethnic nationalism and the idea that there is such a thing as “Swedishness.” Necessarily, that assumes that there are some people who are “Swedish,” and others who are not. So who’s who? And who decides? This is where the specter of race haunts the lives of non-white people in Sweden. Twenty-five percent of the Swedish population has roots outside of Sweden, and many of those roots are non-European. And so when you have a politics that says there is only one way of being Swedish, a fourth of the population is going to be necessarily excluded from that position. The rise of a politics of cultural and racial difference has caused an enormous amount of turmoil in recent times.

In that connection, there's one more song you recommended in the show that has a very interesting history. I think the title translates "Time to Go Home."

Right. The song “Dax Att Åka Hem,” meaning “Time to Go Home,” was released this year on the 8th of September, a day before the most recent national parliamentary elections in Sweden. The song refers to a flyer that was sent out over the summer in July from a minor far-right political party, “Alternative For Sweden,” that read, "It's time to go home" on the front page. It was sent to a variety of people, but the message was quite clear to everyone, that if you are not white, not “ethnically Swedish,” as they say, then after this election, you're going to have to go home. So, this group of young Afro-Swedish musicians got together, created a poppy Afropop tune with lyrics that speak directly to that message, that say, "If the Swedish public chooses this path, the path of the Sweden Democrats, then people like us don't belong here, and it's time to go home."

The result of that election was a hung parliament. So it didn't really resolve things one way or the other. But as far as the song goes, it's interesting that the singers use those words ironically. Surely they don't really think it's time to go home.

I think “It's time to go home” is quite ambivalent. On the one hand, it is saying, “Yes, if you feel this way, it is time for us to go home.” But I think the fact that it was released before the election shows that it was also a call to get out the vote, a call to a broad, diverse Swedish community to say, "No, we don't want to go this route. We all belong here. This is our country and we have to stand up to this." So I think it is both defiant and also a kind of mourning.

So, yes, absolutely people feel threatened. They feel threatened in a very different way than they did in the 1990s. In the 1990s, you have people like the Laser Man (Lasermannen). This was a guy with a rifle with a laser beam sight mounted on it. He shot nonwhite people, or people he thought were “immigrants,” on the streets of Stockholm and Uppsala. To be a person of color at the time was to live in fear. People felt that if they stepped outside, their lives would be in danger. This is part of what Stevie is talking about, the trauma of that moment, that feeling that you are being targeted, literally.

Now, you don't see as much of that kind of deadly racial violence today, though strong anti-immigrant sentiment has resulted in burned-down refugee camps and mosques in recent years. The most potent and public forms of hate crime in Sweden today are anti-black racism and Islamophobia. While the racism may not be as violent as it once was, people still feel threatened by a politics that is shifting fast in ways that directly threaten their personal and collective welfare. And people who have grown up in Sweden all their lives, who were adopted into Sweden, who have known only one home, they no longer feel that the political consensus perceives them as one of their own. And that is definitely threatening.

It’s interesting to note the way some of these minority voices are beginning to make more and louder arguments and claims in the public sphere, although they still don't occupy a significant (or, in my view, sufficient) space in the mainstream media. This means that, too often, debates about current social issues that affect minority Swedes don’t include them. So, for example, debates with the nationalists, the xenophobes, are taken up with more mainstream political actors, who themselves represent, in theory, a broader Swedish public. But even they tend to exclude these minority voices. There are very few people of color in the Swedish parliament, for example. So what I'm seeing is, yes, a lingering tension—or gap—in Swedish society, but also this third space produced and occupied by what we might call the "New Swedes," who are staking classism on these debates and saying, "We will speak for ourselves, thank you! This impacts our lives and livelihoods directly, and we aren't going to take it anymore."

So people are standing up. No question. There is resistance, and Sweden is, like many places right now, at a crossroads. I am following the story of those who say that another Sweden is possible, and I'm encouraged by the fact that their voices are so loud and strong and artistically compelling.

Thanks so much, Ryan. You're doing great work. And we thank you for inspiring and helping so much with this program.

Thank you.

Related Audio Programs