Ezekiel Olumakin, a.k.a. Saint Ezekiel, is a Nigerian-American artist out of Philadelphia. Afropop had not heard of him before this year when he released his debut CD, Everything is Under Alarm, a fitting title for a 2020 release! So Banning Eyre reached out for an interview, and was pleased to discover a fascinating diaspora story from an artist with a remarkable perspective on events in Nigeria and beyond. Here’s their conversation. (Feature photo by Ritchie King)

Banning Eyre: To start, just introduce yourself.

Saint Ezekiel: I grew up in West Philly, and in the morning, we would get up and pray and everything was completely in Yoruba and Hausa. Then we would go out into the world and it was English or occasionally some Greek or you would hear some Chinese, or some surrounding language. But when you get back to that doorstep, you're in Africa again. You're in Nigeria. So it was really interesting growing up the way my parents raised us, which was very, extremely culturally intuitive, culturally aware, so we would not have any means to forget who we are and where we came from.

Musically, my father was a fanatic. At the time you had Ebenezer Obey, Sunny Ade’s juju music, and then you had Fela Anikulapo Kuti. He was someone that my father listened to all of the time. So those were like the three Yoruba artists we were focused on. And I would ask him, "Dad why are we listening to these songs that are 13 minutes long? Turn it off." But I came to love and appreciate those artists, and eventually came to learn and develop techniques after those artists.

So that explains the Yoruba, but you said your folks also spoke Hausa.

Yeah, my mother is Hausa. They are both from Nigeria, and they both speak each others’ language. They had an interesting story of how they met. My father was going to school in the northern area. He was just passing through for a little bit, and my mother… One thing led to another. One meeting there, one meeting there. And then my father goes to the States and one day my mother gets a call and it's this guy that she linked up with for a little bit. He's in the States, talking very sweet. He's in America now and he can bring her to America. Long story short. Here we are.

Did he come as a student?

I'm sure my dad finished his studies back home, but also wanted to further his education in the states, so he was actually going to a local university in the Philadelphia metropolitan area. I think he went to Cheyney. So we are real Philly cats. Philly first generation. He went to university here and furthered his education more after that, and we stayed in that Philadelphia region for at least 15 years of my life.

When were you born?

1992.

What's been your experience of actually going to Nigeria?

Yeah, when I was 12 years old, my father was like, “O.K., I've had enough. Everyone get on a plane." So we all got on this plane. My two brothers and I got on this plane, and my mom. And we’re in Nigeria suddenly. And it was one of the most visceral experiences of my life, because you get told about a place your entire life, and then you finally see it and all the stories, all the food, the language all makes sense. It's something within your DNA, just response to the land itself. So there I was in Lagos as a child who has just heard stories about what Nigeria is like, or just watched a bunch of African films, Nollywood films that we would watch with their terrible effects.

Yes, they don't exactly convey all the realities, do they?

No. So it's quite a different worldview, a different worldscape. And seeing it was just like: Wow! It was transformative. It left an indelible mark on my conscious and subconscious behavior as a black person moving through the world, and continued to inform me about how to be a better individual.

And you've been back.

Yes. I haven't been back for a few years. I've mostly been to Europe. But I need to get to Nigeria as soon as possible, so I'm waiting for this COVID to drop.

There's a lot going down there at the moment.

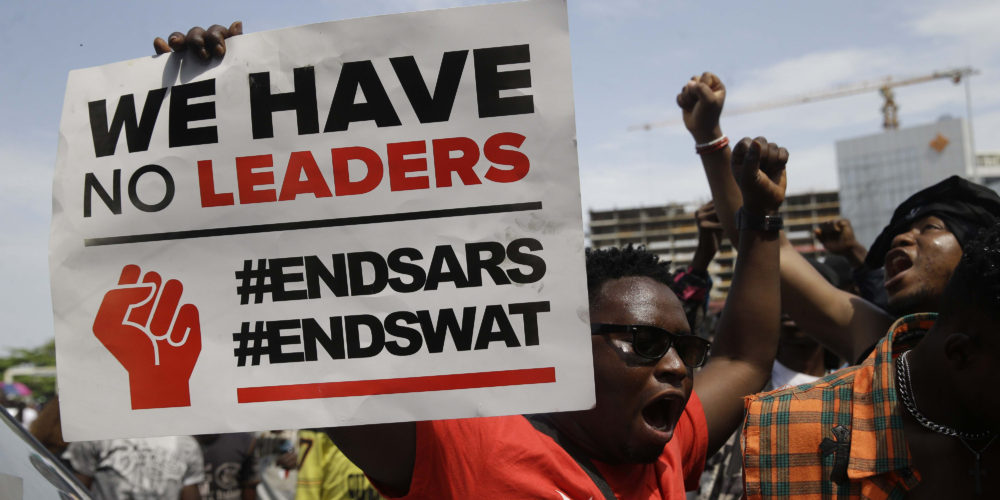

Oh man. Yes. The End SARS [Special Anti-Robbery Squad] movement. Remnants of neocolonial sentiments that have extended from the ’70s and the inception of Nigeria as a state are now bubbling up to the surface, and we’re seeing the ramifications of the world not doing its due diligence in terms of checking African nations in their growth and their development. It is quite a sin to see. It's a tragedy.

And it's been fascinating to see how artists are responding.

Yes. And I salute many of the contemporary artists who are Afrobeats with an “s” musicians. They are taking to the streets. Burna Boy has been extremely vocal. Oxlade has been extremely vocal. Bankulli. The guys at the top are very vocal, which is good. However, we are still putting out music, which is kind of interesting to me because it's like music seems to be the number one cultural export out of Nigeria right now, and it is setting the pace for many of the African communities. I dare say that it's giving rise to the spaces that now are occupied by other genres like amapiano coming out of South Africa.

If we have that much of a footprint on the global perception of Africa, then why haven't we come together in a corrective movement to make a unified statement or a unified front to stop the music in order to stop the violence. Stop the music to use that silence to drown out the noise that's being perpetuated by these—again I use the word—neo-colonialist gaffs or specters. These are now ramifications that we’re suffering from decades ago. The same people that Fela was fighting in fact are still in power. We need to use our platforms in a much more efficient and unified way, I believe.

That's a bold idea. Silence. Is anyone actually advocating that?

I'm not sure. I'm not directly plugged in with all the cats back home. I know that some of the top guys know me in passing. “Oh that guy worked with these guys and now he's doing this.” But they don't really know who I am, so I can't really inform them or spearhead any kind of movement just yet.

I want to talk about more about the Nigerian scene. But let's stick with your musical journey. From what I hear on your album, your music doesn't fall easily into any genre classification, which is something I like.

Yes. Music for me has always been an escape, a therapy, a means of coping, a means of expression. As it is for most people. I started playing piano because my older brother was playing piano and I wanted to be like him. So we would go to do lessons with this very old lady in our neighborhood. And she teaches piano and I start taking lessons, hour-long lessons, after my brother. I hated it, to be honest. I didn't like reading the sheet music. I could read it, but I just didn't like looking up and down and up and down and up and down. So what would happen is I would just memorize the melody by ear that I was supposed to play, just listen to it and I would play it out. And that worked on till the instructor was like, "You're not reading, are you?" And I was, “Nope. It takes a little bit too long for me to do that. This is better for me. I find it easier to assimilate knowledge like this.” Then I resigned from piano at like, five years old. “I don’t want to do this anymore!”

It was so funny. She was like, "You are a disgrace to the piano." This is what this woman said to me. And I was like, “Oh, all right. Cool.”

My brother, being a musical savant, had started saxophone lessons. And I was like, “All right, I'm not going to make the mistake of doing the same thing he's doing again. I'm going to play trumpet." So I picked trumpet and I'm playing horn for like nine years. My brother and I are playing in churches, these West African churches. So we are playing together and we get pretty good.

The way musicians are chosen at churches is just like one day somebody's absent, and it's like, “Jo, can you do that? Or can you do this?” So one day somebody wasn't there next to the guitar, and I just picked it up and I started playing. And I liked it. I liked the way that guitar can be both a lead and a background instrument. I just taught myself how to do that, and that's what I've been ever since.

Do you still play trumpet?

Once in a while I pick up the trumpet. You'll hear a few lines here and there. But I really kind of traded my chops. I think I'll get them back in a little bit once I focus on it. But no Hugh Masekela lines just yet.

I relate to that. I tried a few instruments before I got to guitar, but once I was there, there was no turning back.

Yeah, guitar is just something where it's like you have this gigantic dream in your hands. You're rocking out and you're playing smooth or blues. There's just so much power you can command with that. And the imagery of just standing on the stage in front of a crowd of people, just playing. It's just beautiful. It's something that every kid can have at some point in some way. That's where my childlike wonder begins there, in terms of the lure of the instrument.

That’s good to hear, because guitar is actually less popular now than it was when I was your age. Music has become so electronic and computer-driven. But guitar will never die.

Of course. Guys like Isaiah Sharkee and Jairus Mozee are bringing back guitar-based music and just being virtuosos of every single style. Isaiah Sharkee is John Mayer's guitarist now, as well as he plays for D'Angelo. Jairus Mozee is a guitarist, producer, bass player. Those two in my opinion are just shattering what it means to be a guitarist. Jairus Mozee as an album out now called The Secret Garden. If you get a chance, you should definitely listen.

Coming back to you, did you start right away writing music?

When I was starting to play guitar, I was listening to a lot of math rock. I was listing to another West African guy who was born in DC, I believe. Tosin Abasi of Animals as Leaders. That project is just prog rock, math rock, hard-core music. And in high school that's mostly what I was listening to. Dance Gavin Dance, The Fall of Troy and things like this. To me though, it seemed like those musicians were just playing jazz and blues sped up with a bunch of distortion. So I would listen to that music, but I would try to learn Wes Montgomery's music. I would try to learn George Benson's music. That was and still is my bread and butter. Wes Montgomery every day.

You can't go wrong there.

No, no. So I wasn't necessarily writing parts. I was just playing whatever it was that people needed at church, mostly I IV V progressions. Kind of like chopped and screwed. Congolese or soukous-type rhythms when needed. And a little foray into syncretic rhythms really. Just kind of playing something African through an American lens, for an African audience.

At the same time, we were being introduced to all of this fuji music and juju music, contemporary gospel music like Yinka Ayefele, Megga 99 and all these cats. And these guys are coming over to the states and performing. So you go and see the concert. At the time, Mike Fasheke was a promoter and a big brother to us, a mentor musically, and he brought all of these guys. So me, being like a kid and a younger player, would go and watch them play at church the next Sunday, or at fundraisers on Saturday.

This is for African audiences, right?

Predominantly West African, I would say predominantly Yoruba audiences. All of the shows were in Yoruba, so you’re hearing the latest talking drum solos. That went on for maybe 10 years. Just watching this subculture unfold in D.C., New York, Philly, Virginia, and maybe even sometimes Florida and Georgia area.

Fascinating. A world I have no idea about. That sounds like an education in itself.

Yeah, man. I really cut my teeth with a lot of amazing musicians that I've come to know and love and respect.

So how do you get from that to this EP?

Yeah, so I went to school, because education is paramount in a collectivist culture family. I went to do the whole degree thing, I studied at Rowan University, and then I studied at the New School of Public Engagement in New York.

What were you studying?

The first time liberal arts, mostly French and psychology. But I didn't want to declare anything, so just liberal arts. The second degree is in international affairs and human rights, with a concentration in global governance. So if you have any connects at the U.N., plug me in.

So how do I get from there to here? Shortly after I graduated with my Masters degree, I went to Cuba with Gabriel Vignoli, who is a professor at the New School. This was a transformative experience in which I learned a lot about the diaspora, its connection to music, and the importance of spirituality as conveyed through the medium of music. This propelled me forward immensely. I had always been playing music, but I took a hiatus while I was in school. And for a while, I was just unconcerned with music. I gave up. “I'm not going to be a musician. I'm going to work in an office. Blah blah blah.” There were no gigs. There were no calls. I stopped playing at churches. There wasn't really anything.

But later in that year, my older brother comes up to me and says, "Yo, man. There's an open mic thing happening at this place called the Green Soul Café, in Philly. James Poyser [producer and keyboard player for The Roots] it is going to be there.” And I was like, “Who is James Poyser, and what does he have to do with us?”

And he's like, "No, man, it'll be great. You got to go." I was like, “No I'm not going to go. I haven't practiced. Haven't played guitar seriously in a few months and I'm not going to go embarrass myself.” He was like, "Nope. You're coming. We’re making this happen." And so I go to this performance. I take my guitar. I don't know if you know Philly musicians, but they're absolutely incredible. Is just one of the most intimidating rooms I've ever been in, but the same time everybody's welcoming cool. I'm just playing a little bit of guitar, strumming along the side, and this guy comes and he's like, "Yeah, man. I want to play guitar." So I get up. I'm like, “O.K., bye.”

The format of the performance was that the DJ would play a song. It was DJ Active that night, also a Philly native. He would play a song, and then James and his band would start playing the song the DJ was playing, and they would groove over that while people would come up and sing. And so late into the evening, I point to my brother and start packing up my stuff. He said no, man. Just stay a little bit longer. Then the next song the DJ puts on is “Shakara” by Fela.

And my brother is like, "Yo, you got to sing this song. You got to kill it real quick. If you don’t do anything, you might as well just do this and then you can leave." And I'm like, "You are correct, sir." So I walk up to James, who does not know me, and I'm like, "Yo, man, can I sing the song?" And he's like, "What are you talking about, brother? This is an African song. Just chill out.” And I was like, "No, man. I'm West African. I'm Nigerian. I can do this." And he's like, “Oh, all right. Cool.”

So I get up on the stage and like, I butchered the song in broken Yoruba, but these people are just loving it. They’re screaming. “This is great!” I was scared. I was shaking. And it was like, “No, man, you’re killing it right now.” And the whole room just erupts with dancing. And this little ethereal dance party is happening for like five minutes. So I get off the stage, and I go home, and I go to sleep. I wake up the next day, and I have a message from the drummer that was there. “Man, you really killed it last night. James wants to see you."

I'm like, “James was to see me? What are you talking about.” “James Poyser wants to meet with you. Let me send him your number and exchange numbers." So James gets my number. We play phone tag for a bit, and then we have a conversation. And he says, “I would love to link up. Let's meet." We end up meeting the next week at Jazzy Jeff's house. Which is pretty intense for me. Because I'd only seen this man on TV before.

In that house are a stellar bunch of musicians. You have Mumu Fresh, 14 KT, DJ Kaloo who was a producer for the likes of Kanye West, Dr. Dre, Eminem. Real musical powerhouses. And the rest is history. That's how I got here.

Amazing. Did you decide then and there that you had to do music?

At that point, it was just like, “O.K., you want this. You can either do this or do the other thing you were thinking about." It was a crossroads moment really where fate, God, the universe… If you want this, here it is. You have put in the work, if you want it now, here it is. You can't turn back.

How long ago was that?

That will be three years ago in December.

Wow. Recent.

Yeah. And then little by little, wonderfully beautiful accidents would occur. Like playing a tune and having an artist watch that tune and send it to somebody else. So, for instance, I met one of my very great friends and musical mentors, Oddisee, just by playing a song online on Instagram. And he followed me. Oddisee has a Sudanese background, and is such an interesting, musically talented guy. We just met by accident and now I've been playing in his band Good Company for, I guess, about a year. I wrote some songs on the last album, and a few more in the works.

So this album, Everything is Under Alarm is the first thing you have put out under your own name?

Yes. The St. Ezekiel moniker for the most part has been just guitar parts that I've laid on their songs. But this is the first with instrumental, vocal, complete project that I've put out under this moniker.

What was the process like?

That's an interesting story on its own. I was at Jeff's house, and I meet this guy named DJ Mel Starr from the New York area. Mel is like, “I think we could work on something kind of cool, something crazy.”. I kind of brushed it off, but then I get another call, “Yo. It’s Mel. Let's work.”

O.K., this guy's serious. So we start developing these rhythms. He sends me different cadences. Then I sent some stuff to them back. Let's do it like this. Let's change this. Or let's put accents here. Or let's leave this part out. Let's increase more presence of this instrument. And then he created these drum loop tracks and sent them over to me, and I played guitar over them, used different effects to play horns, guitar, and really kind of developed the sound. Then I sent those tracks over to the music director for Good Company whose name is Dennis Turner. He's a very talented bassist and he sent them back. Then we sent those tracks to Eric Lau. Eric is an absolute legend of a producer and a mixing artist, mastering sometimes as well. So he did a bit of sound design of most tracks afterwards. And that is how the EP came to be.

One thing I noticed right away is that there are a number of different languages woven in. Talk to me a little bit about the messages in the music.

We definitely have a few languages. Spanish starts out at first. There is some English. And then we have Yoruba towards the end and in the middle of the album. The Spanish portion that we’re listening to in the first song, "La Raza,” that was taken from a lecture by Gabriel Vignoli and Rudolfo Rensoli. Why this is important is because it's talking specifically about race-making in the nation of Cuba. Cubans are typically are darker and look more like me, which is why I wanted to be there, which is why I felt at home.

The Cuban connection is interesting for you, because it's not just African, it's very specifically Yoruba to a significant degree. Other than Cuba and Brazil, you don't really find that culture represented so strongly anywhere in the New World. I expect you were fascinated by that.

Utterly. I felt more at home in Cuba than I did in Nigeria. I felt the energy of the people, the understanding of the people, the appreciation of just our culture so much so frozen in a time capsule due to the nature of the Cuban politics and so forth. Rodolfo Rensoli is the foremost recognized father of hip-hop in Cuba, pop culture as a form of resistance and discourse. So it was a beautiful lecture that I have the opportunity to happen upon, and I have the file, so…

Cool. What about the song “The Black Prayer”?

In “The Black Prayer,” you can hear the voice of my father praying. I spoke to him and I said, "Dad, what would you say to God about the pandemic? About black bodies being laid in the street being shot by police officers both here in the states and at home? What can we do?" And he said, "All we can do for now is pray. And when we pray, the answers will be revealed to us and you can take action." That is a beautiful heartfelt prayer that he rendered, not for me, but for all of us. That's why it’s entitled "The Black Prayer."

How about "Flee to the Amazon"?

“Flee to the Amazon” is a fun song. During the discourse of the destruction of the Amazon by Bolsonaro and the autocrats that were clearing indigenous tribes and land away so they can harvest meat or create grazing farms for beef, because that was a good export, a lot of people were literally fleeing from the terror zone. And there are these fires that are eating up the lungs of the earth, literally. Quite literally. And so I thought it would be interesting if we all returned to the Amazon and stood our ground and rested our roots in the lungs of the earth, and really sunk down. And I looked at it as the Amazon being present within all places, all cultures, all people. But people don't want to recognize what is supporting the whole system, which for me, is black women. So there are a lot of similes and metaphors to a black woman in the song. But it is an anthem dedicated to just that, the lungs of the earth.

I see references to Lagos in “Ikeja Dreaming” and “Ring Road.”

Yeah. This whole entire EP for me was like… I see so many films that are beautiful and built off coming-of-age experiences, and wanderlust. The theme of wanderlust, and just being able to ride a bicycle down Venice Beach and how the palm tree motif there and that whole new view of freedom, and in my heart and mind while writing this, I wanted to see what it would be like if there was an African motif of freedom, peace, of reckless abandon, of learning, of joy, of falling in love. And if there was a film to go along with that. And there weren't any for me, really. We're just starting to get these kind of coming-of-age films in the Black diaspora. Like the film Dope, or something like Banana Island with Donald Glover. We are just starting to get this imagery, like Beyonce’s beautiful depictions of Africa and fantasy. But we can't necessarily materialize these things or manifest these things if we don't see them. If there is no model, how can we aspire to be that?

Let’s talk about Nigeria. You mentioned the activism of Burna Boy and others. One of the discourses that we explored when we were there in 2017 was the paradox of an emerging generation of artists who take the name Afrobeats, echoing Fela, but who really don't embrace the spirit of activism that was in his music. They tend to sing about aspirational visions of wealth, power, romance. These are natural subjects for pop music anywhere, but it seems remote from the instincts of Fela’s Afrobeat. What you think about that? And do you think it's changing in this current moment with activism coming from major Afrobeats artists?

That's a really interesting question. Fela was an unusual individual, his family being involved heavily within the political scene, the work that his mom did, the proximity to Nkrumah, his own revelations of blackness, and his understanding of seeing it through a Western lens first in London during school, and then again in the States. Now these contemporary cats are not functioning under the same context that Fela was enduring. He didn't believe in any other kind of music aside from protest music. He believed his entire existence was being politicized. Whether or not he wanted to be involved in politics was not the question. The only other artist around this time to do this in the same vein as successfully was Bob Marley. In some ways they weren't really musicians. They were revolutionaries who just happened to be involved in music.

Flash forward to today, you have people who are living in a brand-new Nigeria, a brand-new world. There have been several advancements in the last decade in terms of policy and relations amongst different sorts of people. How they move through the world has been deeply influenced by these advances. I can't fault anyone in Nigeria for shifting the focus of the music to aspirations and models of the West, or of popular culture. Since the 2010s, things have been coming out quite aggressively and quite successfully from this West African region. But the priorities of these artists are much different. They're trying to use music as a vehicle to make their lives better, their immediate circumstances better. I think they all understand that there is poverty, various government corruption, or there is this or that. But the unfortunate reality is it might be so ingrained in their everyday that there is no litmus for identifying corruption. “All right, this is here. What am I supposed to do about it? It’s too massive. Let me just make my music and go.”

I hear that.

Burna Boy is an interesting case in terms of this. A lot of his music is directly informed by Fela. I think his grandfather used to manage Fela, and he spent a lot of time around Angelique Kidjo. So you can hear a lot of the rhythms and statements. He's paying tribute to them by literally sampling them, either using melody, a phrase, and building a new song off of that, which is very cool. I like that. And most people are like, “Wow. This guy really respects the tradition.” It would be interesting to see him move more aggressively into making these statements the way Fela did. But at the same time, you can't ask this of anybody. You can't go and say, "Go, sacrifice your life."

Every artist back home is fighting, I give them all credit, because it is an incomprehensible reality that we’re facing right now. It must come to an end, and every bit of help is much appreciated, from sampling of Fela’s music, to Beyoncé highlighting Africa and telling us to find our way back. All those things are needed.

Do you think this moment, particularly with the End SARS activism is just a continuation, or is it a turning point? These artists are stepping into the fray, and taking some hits for it. That hasn't happened much during the Afrobeats era.

It might be. We might be seeing a turning point in the way people relate to Africa from the outside, and the way Africans relate to themselves on the inside, particularly government, older generation, collectivist culture, and the influx of younger individuals who are being exposed to different things. You're talking about individuals who have spent half of their lives either in the West or were at Western schools in Nigeria, who are relating with expatriates of different nations in learning that, “Oh, wow, this is not the only way I can live my life.” And so culture is transforming.

In my opinion, we’re watching a failed state, a remnant of the British Empire, continuing to wear the trappings an African nation operating with extreme corruption. But because the End SARS campaign has been blasted out to the entire world via social media, now Nigerians function similarly to English people, where they like to have face. Most collectivist cultures have this concept of face. You don't want to have your face besmirched. And the End SARS movement is doing that, right? It's bringing light to government and bringing a lot of shame to the country.

A lot of the local discourse happening sees politicians attacking protesting youngsters as “thugs” that are doing this to our country. And then the inverse is these old corrupt bigots and demagogues ruling over us. I think there is a transformation coming, but it won't fully come until Nigeria takes responsibility for its neocolonial sentiments and really does away with them. The people currently holding offices need to let go and relinquish power in order for new governance to give hope to this country.

I think Americans looking at the End SARS movement inevitably see it through the lens of Black Lives Matter—the point of connection being police violence. In America, it's all about black and white, about race. But there's an overriding reality of authority taking advantage of poor people, free-thinking people, rebellious people who want to upset the status quo.

Of course. I think the problem with saying it's just about police brutality is that police brutality is simply a symptom. The police brutality in Nigeria is occurring for entirely different reasons. The police are underpaid. The police live in shanty homes. The police don't have health care. They don't have access to education. They don't have upward mobility. They don't have pensions. Of course they're going to extort people for their money on the side of the street, but that's just one portion of a greater systemic destruction of African people. This occurs all over the African continent but it's being highlighted directly in Nigeria because of, one, the participation of the artists in this campaign, and two, how massive Nigeria is, how integral it is to industry in the surrounding area. And so it's just a mess, man.

Well, I'm curious to see if this turns out to be an inflection point, because Nigeria now has such a big megaphone now.

Of course, and music is the weapon, as Fela said. If more people utilize music as a soft power, for instance, if a Beyoncé would come out and speak about this, or hold a conference and have a discussion about this, that would be something.

I read that Tiwa Savage was putting some pressure on Beyoncé to do that, and I guess she did make a statement.

Yes. But see, and I don't mean to be overtly critical of anyone in regards to activism, because everyone understands their own identity and space with things differently, their proximity to things differently. But if you come to our Africa and you use our backdrop of our milieus of rivers and our people, and use them as props for your videos, it is your responsibility to give back. You could pay those people; that's fine. But there will be no Nigeria and another generation if we are not protected. And it no longer matters what the color of your skin is. If you have the economic power to do so, you can buy yourself out of your race, and begin to act as though… It's like, “Well, as long as the French aren't doing it to me, if it's Beyoncé doing it, I'm cool.” No. It's the same.

Well, that poses a challenge to what you were saying earlier about the context of today's artists, and how their motivations are different in a different time. I take your point about how things have changed. But like you say, it's the same people Fela was fighting are still in charge. So the context is different, and it's not different.

People today are like, "Well it didn't happen to me. That's not my problem.” But I say, "Bro, if it happened to her, it can happen to you, can happen to your mother, it can happen to your brother, your sister.” I mean, the Lekki toll booth massacre. I mean, what? If this was to happen in any other nation outside of this pandemic, there would be some kind of allied forces intervention, or the U.N. would have said we need to intervene. But this happens in Nigeria when the entire world was sick with COVID. This is a deeply rooted spiritual sickness by the political leaders Nigeria that let this happen. And more so, the zombies who went and pulled the triggers.

I'm very hurt by the whole situation. I wanted to return to Nigeria immediately because now I’m older, wiser and I have a little bit more mobility. I definitely want to go and hook up with a lot people back home and start working with them. Now I feel like I don't have a home here in the States and I don't have a home back there either.

Well, on that cheerful note…

Got to keep pushing. And ultimately, music is creating this upward mobility of opportunities for me and allowing me to create my home wherever and include whoever I want, all people into my family. So I am blessed for that.

Thank you so much. This is been a wonderful conversation.

Thank you. It was an honor to be here, and I definitely can't wait to talk to you more about the next things that we’re working on.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles