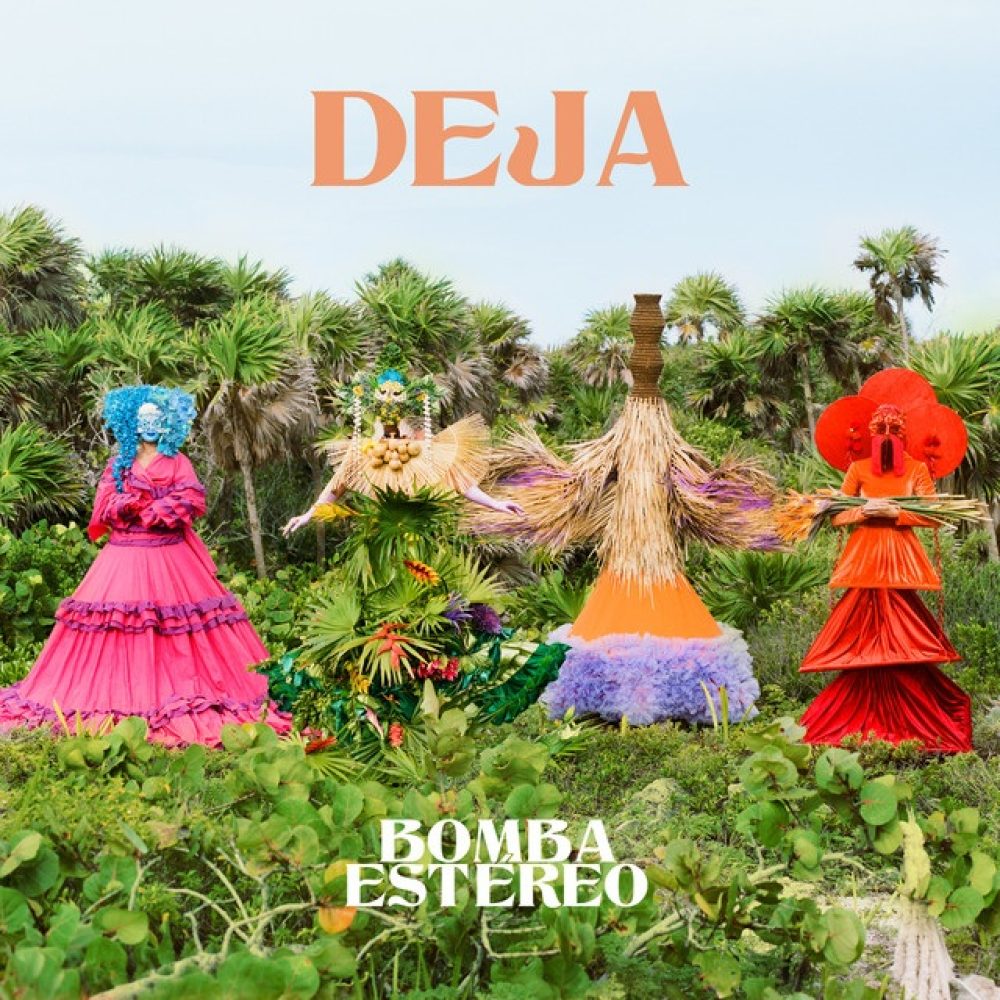

Simón Mejía is the founder of Colombia’s groundbreaking electro-tropical band Bomba Estéreo, famous around the world for its ingenious fusions of roots sounds and contemporary dance beats. Their sixth studio album, Deja, was released in 2021, and in the summer of 2022, they are beginning a pandemic-delayed tour to promote the album. Tour dates here.

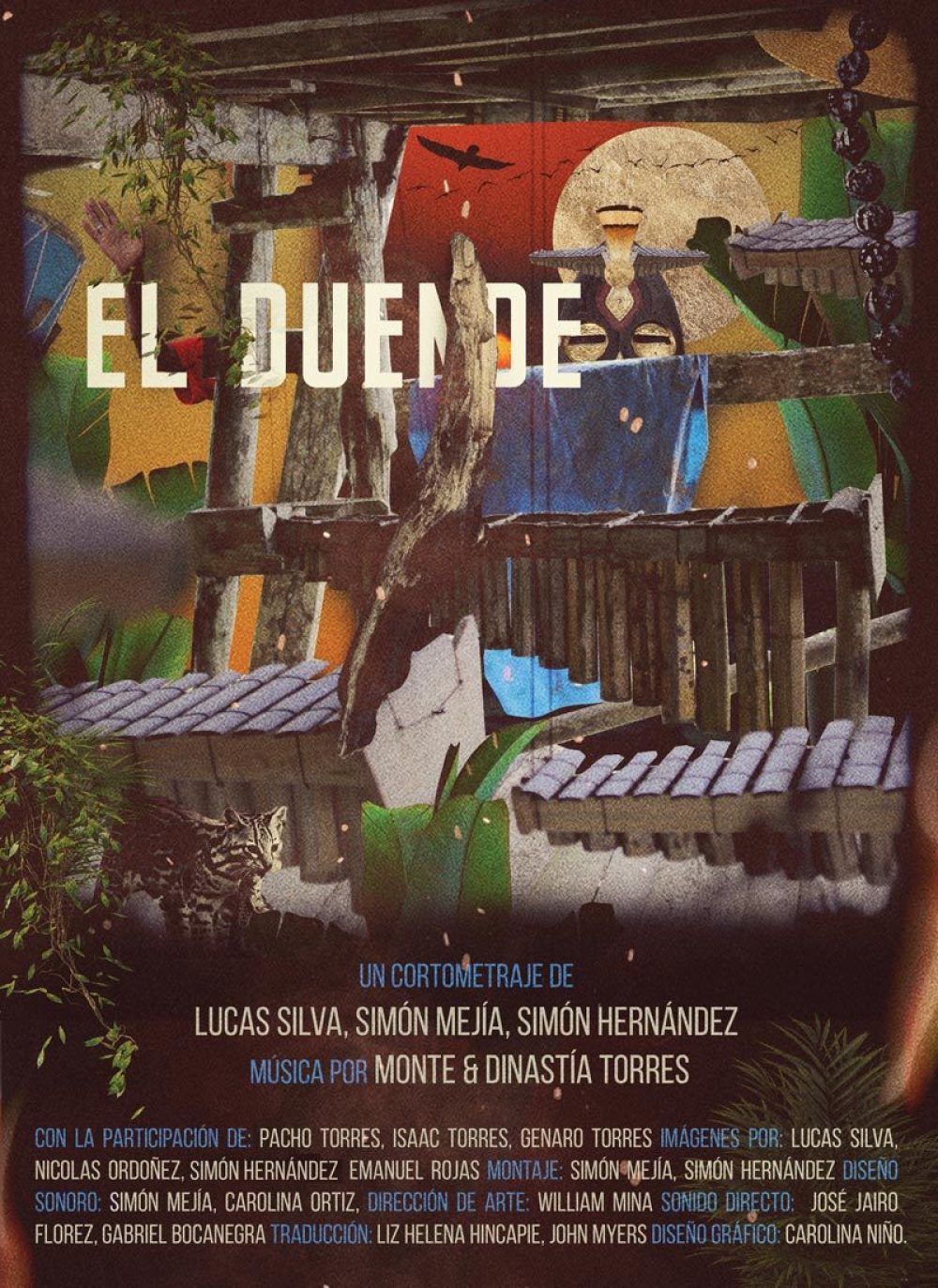

Aside from his work with Bomba, Mejía is also a remixer, a filmmaker and a champion of all sorts of Colombian music, particularly the indigenous and African-rooted traditions. His most recent creation is a short documentary called El Duende. The title refers to a magical being, an “elf,” that long ago taught African descendants in the Pacific Coast region of Colombia how to make and play a particular kind of marimba. It’s an enchanting and mysterious film, a kind of visual remix of songs from the album Los Duendes de la Marimba by the Torres family, Dinastia Torres, carriers of this unique Afro-Colombian tradition. You can hear the first single from Mejía’s remix album “Mamita,” here. Mejía will screen El Duende at NuBlu in New York City on July 22, the day of its official release.

Banning Eyre reached Mejía over Zoom to discuss the project. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Simón, am I reaching you in Bogotá?

Simón Mejía: Yes. I am in Bogotá. Last week we were in Spain. So I may be a little confused about time.

That may be appropriate for a discussion of this film. But first, I've been reading that you guys are facing big changes on the political scene in Colombia. How's that going so far? [Gustavo Petro and Francia Márquez were elected president and vice president in June, 2022.]

Yes. Big changes, but good changes. It's crazy because the economic community is scared. This is the first left-wing government we've had in the history of Colombia. Why? Because especially in the ‘70s and before, whenever we had left-wing candidates for the presidency, they killed them—at least three of them. So this is the first left-wing president in the history of Colombia, and also the first Afro-woman vice president. So for me, that alone is fantastic. But you know, people with money are scared.

I imagine that candidates on the left might be a little scared too, given that history.

Yes. But I think it's good times for Colombia. Hopefully good changes are coming, especially for people who've been having a really bad time here. There's hope in the air. Banks and people with money are scared, but roots people are having hope, and for me, that is good.

Well, good luck. I hope this new government exceeds expectations. It won't be easy.

It won't be easy, but hopefully he will do it. You never know with politics. Politics is so crazy, all over the world.

Yes. We used to think we had relatively sane politics in the United States, but that's kind of over now.

Yes. I know. I know.

Well, this is a very interesting project. I was just looking back at our last interview with you, which was during Covid. You were very much working in the studio. Now this project takes you to the Pacific Coast. Is that familiar territory for you?

More or less. The Pacific here is a very big jungle. It's not so easy to go there. It's very expensive and there are no roads. You get there by a small airplane or by boat, and then inside the Pacific, you can only move by rivers. There are no roads. It's really complicated, but that makes it beautiful. After the Amazon jungle, this is the second most important jungle in Latin America. It is a huge lung, and a huge music lung as well. I've always been fascinated by that music in the Pacific, which is really different from the music in the Caribbean coast.

The meters are different, the harmonies and the instrumentation… It's a very different universe even though it comes from the same root. The music in the Pacific is more Afro. In the Caribbean, it's more of a mixture between African and indigenous and white. In the Pacific, the Africans were very isolated, so it's more of a pure Afro region, and that makes it musically very interesting. You find things that you would otherwise only find deep in Africa, the marimbas and all that.

I have had in my mind for a long time to do something with the music there. But the Caribbean coast, and Colombia and Bomba Estéreo has been taking up all my time. I've never had time to explore there.

You live in a very rich country when it comes to culture and music.

It is. It is. We have the indigenous culture that was already here, and then the African diaspora. That influence is really big. And I love that we have an Afro woman in power now. I hope that will bring the Afro music more forward.

We've paid some attention to the music from that region, particularly the group ChoQuibTown.

Yes, but then there are the marimbas and other instruments. There is not so much indigenous culture as on the Caribbean side. But it's more psychedelic, and more roots. They didn't have so many influences over there.

I don't know if you have met our colleague Ned Sublette. He is leading a trip to the Pacific Coast of Colombia in August, 2022. He has a very interesting organization called Postmambo Studies.

That's interesting.

So let's talk about this marimba. I'm familiar with some related traditions in Africa. The way those traditions came to the Americas is rather mysterious as best I can tell. What do you know about the origins of the tradition you draw on here with the Torres family.

I'm not quite sure, because when you ask them they have a kind of blurry story to tell. What I can conclude about that is that when slavery came to Colombia, some tribes stayed in the Caribbean, and others went to the Pacific. And those in the Pacific must have had that kind of tradition in Africa. As you know, when you explore African music, you find marimbas, but you don't find them the way they play them here. There's something happening here that nobody quite knows.

A lot of years have gone by. How would you describe the difference?

I don't know. It's kind of strange. When they sing, they sing in Spanish, but it's Colombian. It's difficult to say in words. I think it has something to do with the territory, with the jungle, with the rivers flowing there, with the rhythms that come from that terrain. I'm not sure I have a better answer than that.

I understand. But tell me how you met the Torres family.

I met them through Lucas Silva from Palenque Records. He introduced me to them, and then a few years ago in 2008, I was doing a big research on Afro-Colombian and indigenous music with a friend of mine and we were working in Palenque on the Caribbean coast. We went there and set up a mobile studio and filmed a documentary as well. The next step was traveling to the Pacific, and Lucas had told us, “You should go to these people's house, the Torres family house in Guapi. It's emblematic of the marimba music of that region."

We went there. It was just beside the river. We spent some time with them. It was a great experience, because the house they lived in is not there anymore. It fell down.

Is that the old house we see in the film? Right on the water?

Yes. It fell down. It’s right on the water, and you can kind of see that it's tilting towards the river. We went there, and everything was tilting. We had to put the camera at an angle, because it was like falling into the river. There were marimbas hanging from the ceiling, and everything was shifted. We spoke with the guys, and they seemed like crazy people. Everything was twisted.

But the more time you spend with them drinking this traditional alcohol called biche the more you get into the music, and the better they play. Biche is a kind of sugar cane alcohol. So we met them there and we did some interviews, and they played a lot of music. We did some recording. But we didn't use that for this project. That was many years ago.

For this particular work, Lucas reached out to me again. He told me that he had recorded this album with the Torres brothers. Obviously we remembered these guys. So he asked me to do some remixes. He sent me the stems of the recordings he had, and I started making the remixes and in the middle of it I told him, "We have to do something visual with this.” We have to tell the story of these guys, the story of the Duende and everything. So the remixes turned into a short film. That was the process.

At the same time I was very impressed with an album by this band Soulwax, an electronic band from Belgium. I was listening to them and I got to an album that was kind of a documentary. It was about a place where hippies went in the ‘60s and it was very free. You hear people talking about this history, and then this electronic music on top I was very inspired by that album to make this one about El Duende. I wanted to hear people speaking and telling stories behind the music. But then I felt we had to see it. So that's how it became a short film. It was all a process of experimentation.

So where did the footage in the film come from?

That’s Lucas’ footage. So it's kind of a remix, a film mix, and everything mixed up. It's a collage of things.

So now I think you have to tell us the story of El Duende, the origin story of this particular marimba. Tell it the way the Torres brothers tell it.

It's really crazy. I find this Duende myth-- and it is a myth-- very similar to the story of the crossroads in blues music. This guy goes to a crossroads and he walks with his guitar and meets the devil, and the devil teaches him to play the guitar, to be a genius of the guitar. It's kind of the same with these guys. They go to the jungle for a week without food or water, and they just sit there and wait. After a while, they start to hallucinate, and in the middle of that, this strange being, this devil, appears, and this is El Duende. It's kind of an elf, a magical being. Then el Duende teaches them how to build the marimba and how to play it.

These guys build their own marimbas, by ear. They don't have any formal musical knowledge, no academy training or nothing. They don't have internet. They just do it by ear, by tradition. They cut the wood and tune it by ear, And they play it just the way El Duende taught them in the middle of the jungle.

And this knowledge is passed down generation to generation.

Yes, generation to generation. But there are two types of marimba players in the Pacific. The guys that go to the main city, Cali, they take their marimbas and tune them to the piano and to the saxophone. They tune to A-440. But the ones who stay in the jungle tune by ear. When I listen to both, I deeply prefer the ones who do it in the jungle. It's really unique music. It has that special trance, but the ones that are tuned to a piano don't reach that level.

That is interesting. I have worked with mbira and marimba players in Zimbabwe and Mozambique. It's the same thing. The guys in the cities tune their instruments so they can play with guitars and keyboards, but when you go in the countryside, you find different tunings. And in some cases, each family will have its own special tuning. So when you are with the Torres family, do you feel like they have their own tuning in their heads, and tune all their instruments that one way?

For sure. For sure. And probably if you go to different families, each family would have its own kind of tuning. So the Torres are three brothers, and they play the marimbas together, and when the singers come, they are accustomed to the way the Torres marimba sounds, and their voices have to stick to that particular tuning. It's very unique. When I listen to those marimbas, I understand the way they are speaking. The marimba is like the sound of the river. The melodies go up and down, and there's a flow that never ends. And that's the Pacific. The Pacific in Colombia is all about the water. And for me the music has that feeling, the feeling of the rivers, and the jungle obviously, but especially the water. The water becomes music.

It's very beautiful, and what I like most about it is that when you go there, you are kind of transported into a different era of humanity. You feel like, “Oh wow, I'm now centuries back." It's unique. It's really beautiful.

So when you're working with these recordings in the studio, I imagine that you analyze that tuning. Aside from the pitch tonality, is the scale itself very different from a Western scale? Are the intervals different?

It's really different. If you listen to it, you might feel that everything is out of tune, the vocals and the marimba. “What is the problem with these guys?” But you cannot listen with that ear. You have to listen from other parts of the body. When I'm working here with the synthesizers, I have to manually pitch the synths. It's a really strange tuning, and even when I did this, it felt a little bit out of tune. Still.

That sounds challenging.

And then another thing happens. When you listen to that music on the site, like in their house, where everything is a bit tilted, it will never sound the same as when you listen to it recorded. It's music that is meant to be there with the river beside it, and the house, and those guys drinking their biche, and the heat and the mosquitoes and everything. It sounds different when you record it and listen to it in the studio. It is a totally different experience.

I downloaded the Torres album from Bandcamp. So that is the recording you were using as your starting point, right?

I used the marimbas from that recording, and then some interviews Lucas had done with the guys. I wanted to hear them speaking, to get into the context and the universe of that music. Then one thing led to another, but it was always starting with the marimbas. I find in that Pacific music that the marimbas are more powerful than the singing. The singing is interesting, but it's usually a chorus that repeats and repeats. But the marimbas are the ones that are really speaking.

There's more variation.

Yes. More variation. I also had some other recordings of marimbas. So I started to listen to other kinds of marimbas and different periods of recordings, and then with the testimonies of these guys speaking, it was a process of collage. A little bit chaotic as well.

So you just follow your instincts until you feel it's time to stop?

Yes. I did have a previous trip to the Pacific. I didn't go to their house. This was for a different vision of the Pacific.

Was this Sonic Forest?

Yes. That one. I had been recently there, so I had the feeling the Pacific kind of fresh in my mind. It's a whole feeling. Going there is like going to the Amazon jungle, completely out of the system.

This kind of work that you've done for this film, for other recent film projects you’ve done, Monte, Sonic Forrest, Stand for Trees, it's quite different from what you do with Bomba Estéreo. Talk about that difference.

Well, they all come from the same root. Bomba Estéreo started with the idea of using field recordings and samples from old studio recordings and old Caribbean and tropical music recordings, sampling that and using it with electronic music. But then it became a band and it became a bit more pop. It became more of a pop process, songs with verses and a chorus. So it's more of a pop process even though it's not really pop music.

With this other one, I tried to go even deeper into where the inspiration for that pop music came from. These guys in the Pacific were always telling me that for the indigenous and Afro people, the inspiration always came from nature, the sounds of nature—from the river, the birds singing and how trees sound and the rhythms of nature. So I kind of went into that. Instead of a traditional song structure, you have a kind of ambience of the moment, or a story. In this case with El Duende it's more the story they are telling. That's why I put it into a film. But it's really about what they are telling me, the story behind the music, and the ambience. So obviously you have the music, but you also have the birds, the river, the sound of the motorboat passing…

It’s more open, and you have to listen to with that approach. So I'm not listening to a song. It was to a moment in a particular place that happens to be here in the Pacific jungle of Colombia.

I like the way the film honors their sense of things. There's no attempt to impose a Western structure of rationality. That lets us go into their world. I like that.

We struggled a lot with that. Because we are white people. It's kind of difficult to not impose yourself or to put your vision. It is a difficult task when you're working with these kinds of communities. When I try to do is just be there as I am. “I'm a musician myself from a totally different world. You know things that I don't know. I know things that you guys don't know. Let's just drink biche and see what happens. We speak the same language.”

I've had experiences like that. You do have to put things aside, but you do get to enter into the magic of their reality at least for a short time. You can at least taste it.

Yes. It's rich. And for me it's a huge learning process. You learn how the world is today, how cities are next to these parallel realities. It's fascinating to be able to be in those kinds of places. As I was telling you, it feels like centuries ago.

I have only been to Colombia once, to Cartagena. But it is high on my list of places to visit. Such a rich country musically, and so beautiful. It's funny. Anytime I hear any music from Colombia, it always grabs me. There's something magical about that country. You may find me there one day.

I think it has to do with nature. In Colombia it's so diverse and it influences the music. You travel around Colombia, and you find everything from cities to jungles to deserts. The altitudes vary so much. The African diaspora and the indigenous communities are very strong. And the white Colombian culture is really unique. When you come, hit me up and I will take you to amazing places.

That sounds great. My sister gave me a wonderful book, Magdelena, about the biggest river in Colombia.

Yes. Wade Davis.

It's a beautiful book. I learned a lot from that.

My next film is about Magdalena music. I've been speaking a lot with Wade Davis, they were doing a feature film about music in the Magdelena communities. They say that the origin of cumbia is in the Magdalena. It's a musical river, but at the same time it's the heart of violence in the country. It's like the Congo River, lots of violence happening. So we are doing a very interesting film that should be ready for next year.

That's fantastic. So what are the plans for Bomba Estéreo?

We are touring. After the pandemic, everyone is touring and everyone is wanting to tour, and everyone is getting Covid again. So it's difficult times, but this was needed. music is essential to life. So we have this headline tour in the U.S., and then Europe at the end of the year. There's a strong market for Bomba in the U.S.A., touring for the latest album, Deja.

Well, I hope to catch you in New York. Good luck traveling and touring, and congratulations on this wonderful project.

Thank you very much.

Related Audio Programs