Vusi Mahlasela is a veteran singer/songwriter from South Africa. He has just released his 10th album since 1992, and it’s an unusual look back at his childhood under apartheid, and specifically, his grandmother Ida Mahlasela, who ran a shebeen (speak-easy) in the township of Mamelodi. Fittingly, the album Shebeen Queen digs back into the styles that reigned in the townships in the 1960s and ‘70s, especially mbaqanga. The album was recorded live on the site of Ida’s shebeen. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Vusi by Zoom at his home in Pretoria. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Vusi, so good to speak with you. We have really been loving your album. It’s just great.

Vusi Mahlasela: Oh, thank you.

You know, back in 1987, when Sean Barlow and I were just starting Afropop, we came to South Africa as huge fans of mbaqanga, mqashiyo and kwela. We spent time with Mahlathini and the Mahotella Queens and I’ve never really gotten over the experience. So it’s very satisfying to hear you go back to that material.

You know I felt I needed to tap into the DNA of those people because they really did a great job of exporting the culture and the music outside—the mbaqana, mqashiyo, kwela and marabi. Yeah, I must stand with this typical accent of South Africa. Just like Jamaica did with reggae. This is our sound in South Africa.

Absolutely. That’s a good comparison. So let’s start with your grandmother, how she started a shebeen. Let’s hear about Ida.

Oh, she was so wonderful and very strong. My grandmother Ida Mahlasela. Well, it all started when she was forcibly removed from the place in 1961 where she was staying with my grandfather, Elias. They moved from Orange Free State to come and live in Pretoria after they got married. My grandfather was working at the Pretoria United Dairies. He bought a stand in the Eastwood area of Pretoria. It was during the time of apartheid so a Black man in town at night must carry a permit. So my grandfather worked a little bit late and was coming back home with a permit in his hand. And he met these white guys on motorcycles; they were called the Dark Tails. A lot of white guys who were patrolling the town. So if they found a Black man, you must produce a permit. That’s what they were doing during apartheid at that time. Still, with my grandfather with a permit in hand, they beat him to death. That was never investigated, no justice, even until today. Until I did my research.

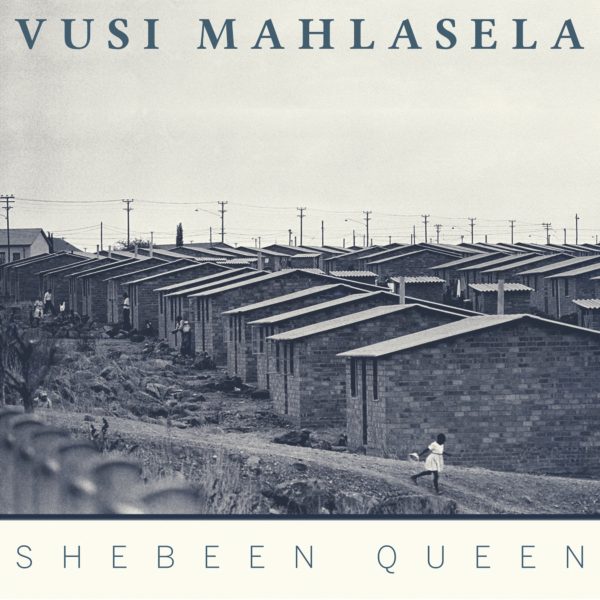

So when you are alone as a woman in the house, during apartheid time, and you don’t have a man, they take you out. They forcibly remove you. So they forced my grandmother to a place called Vlakfontein, which is now Mamelodi, where we recorded the album. So my grandmother moved there with her three children, my mother, my aunt and my uncle. That was 1961, four years before I was born. She didn’t have a job. She could not support herself but she had a skill taught her by her mother, my great-grandmother, which was brewing the African beer, the umqombothi. So she brewed the beer and sold it to the men that were working in Vlakfontein. Those men were working in roofing the houses, as you see on the cover picture in the album. These men were working on roofing those four-room houses, with asbestos. So she would sell the African beer to those men and to the night trash collectors. And the men loved the beer. And the neighboring men also started loving the beer. So she felt like, “O.K., I should start a shebeen, because people love the African beer so much, the umqombothi, African beer. That’s how the shebeen started.

But there were a lot of police raids because from the police, because under the law of the Pretoria municipality at the time, it was illegal for Blacks to sell alcohol to one another. So she was bothered with many raids, the police coming to arrest her and confiscating the liquor and all that. But until the fifth or sixth time at the court, the magistrate asked the police, "I'm seeing this woman here all the time. I am tired of seeing her here. Maybe it’s a different case this time.” And he asked the policeman who arrested her, “What is the case this time?” The policeman said, "No, it is the same case, my Lord." And the judge said, “No, no, no, this cannot be right.” And he asked my grandmother, “Hey, woman, tell me. What is your story?" And my grandmother unfolded the whole story from where what happened when my grandfather was murdered and she was force removed and came to Mamelodi, and that’s how she started this shebeen because she had no way to come up with a plan to fend for her children. The shebeen was the only option. And the magistrate said to the police, "I don't want to see this woman here again. Don't ever harass and arrest this woman again.” And then the magistrate gave my grandmother permission to sell. And that's how the shebeen got started.

That is amazing. Tell me about these white gangs on motorcycles, the Dark Tails.

The Dark Tails was a bunch of white guys with motorbikes, leather jackets and chains and all that. So they surrounded him [grandfather] and they beat him to death, still with the permit in his hand.

But after this magistrate intervened, she was O.K. to operate.

Yes. And then at the shebeen there used to come a lot of characters. The shebeen was called Sgodi Phorla, which means “a place of chill.” And it was also a place of networking. Political meetings were also held there. And there used to come guys, musicians and also gangsters. But they all respected my grandmother because she was no nonsense. They would come to enjoy the beer and the music.

This was happening more on the weekends because during the week my grandmother wanted us to concentrate on our school work and be able to go to school and not get distracted. So during the week, she didn’t want us to be around when these men are drinking and all that. But for me, I was sneaking around and wanting to find out what was really happening. The scene was so great with a lot of characters, men wearing stretch caps, voeps, bellbottom trousers, and two-tone shoes, and women wearing Telerina dresses and berets. Very stylish! And they would dance as if tomorrow would never come. I used to watch that, and the music that was played there, it was mbaqanga, mqashiyo, kwela, marabi and even some mbube. There used to come also these men who were singing at the shebeen, the mbube type songs that have a lot of beautiful a cappela range like Ladysmith Black Mambazo. So I loved those voices. Man, when I heard them I had goosebumps. And they would dance and you would hear the beating of the legs, hitting soft on the ground. If you have seen Ladysmith Black Mambazo doing the dance, and there was a man with a high tenor. [Sings] And they would all join in, and I said, “Wow!” That’s where I started falling in love with music at my grandmother’s shebeen.

Wow. That’s so wonderful. And you said there were political meetings too. So it was all there, the connections you were making between the stylishness, the music, but also the political aspirations for political change so it all went together, is that right?

It all went together. Because there was a man there who took me to a political meeting at a neighboring church close to my grandmother’s house. I didn’t know what was happening there. He just told me we were going to watch music. When we got there, there were some guys playing drums and another one reciting a poem. I didn’t know what was happening, so I asked what they were doing. He said the man was reciting a poem with a background of music. So I asked, “What is a poem?” He said, “It’s a recitation. I’m sure you know that.” O.K., I know that. I love that. So that was the first time I saw a poem being recited over music. And then there was gumboot dancers. And after that there was the national anthem “Nkosi Sikeleli” that was sung. And the man told me is the original one, our prayer, our own, not the one they teach you to sing before you go to classes. This is the original one that you must learn. That was my first political meeting, but I didn’t understand what was happening.

So the one they taught you to sing in school was different.

During the time of apartheid, we were doing the Afrikaans anthem. [Sings] If you sang “Nkosi Sikeleli” that was treason. So that was the first time I heard the original “Nkosi Sikeleli.” It was at that meeting.

But the shebeen was really great. The music was played vinyls—LPs and 45s. They were playing mqashiyo, marabi and kwela and all that. The artists like Mahlathini and the Mahotella Queens, Dark City Sisters, Miriam Makeba—not so much Miriam Makeba because she was banned, along with the Manhattan Brothers in South Africa. And there was a man who lived closely by, who was my mentor, a guitarist and an improviser as well, Dr. Philip Tabane of the music called Malombo. They lived not far away from my place. My uncle told me, “You must listen to this man.” His music was played on the radio. Dr. Philip Tabane. I understand Miles Davis once asked to perform with him but he refused. [Laughs] He said, “My music is too spiritual, I don’t play with other people.” But I was able to play together in 2000, when I launched my foundation, the Vusi Mahlasela Music Development Foundation. I asked him to come and he agreed and we played together. It was such an honor.

I remember Philip Tabane. I met him back in 1988 in Boston. Such wonderful music. And I know his son, Thabang, is making music now. We spoke last year.

Thabang, yes. Thabang is part of the live recording. If you watch the promo video, he is playing the drum there, the African drum.

This recording was made in Mamelodi, right?

This recording was made at Mamelodi, at my grandmother’s backyard. In the street. So we rented a tent and then we publicized the show. People bought tickets. There were security, medics, everything, stage. People could buy T-shirts. And then there were also paintings ranging from Drum Magazine, which was from the ‘60s. And my aunt made the umqombothi, the African beer. Because she's got the touch of my grandmother. And people loved and enjoyed the umqombothi. If you watch in the video, you can just grab the vibe there.

That was the first time that such a thing is done in the township, a live recorded album, recorded in the township. So for me it was not only about dedicating the album to my grandmother. But it was also about highlighting and priding ourselves with this typical South African music, but also, to rubberstamp what my grandmother started when she started the shebeen. That means she started the township economy. That was her promoting the black township economy. So we wanted to bring the Black township economy back into place through the shebeen of my grandmother.

That's wonderful. You know, I play guitar, and I am very impressed with your guitarists. Who are they?

They are young guys. And I tried to get them interested. I told them, "You know, guys, I know you love jazz, but there is something that you need to learn and tap into the DNA of this music. Because this is your music, by your people." And they know about the music. They must learn the guitar riffs and everything, and if you check the band, there are no keys there. There is no keyboards. It's only guitar, bass, drums and the African drums and the saxophone. The saxophone guy is very young, and he is a well-trained soldier as well. And then one of the backup vocalist, he plays bass. He is a principal at my school, the Vusi Mahlasela Academy.

So I am trying to develop these young guys to get into this music of mqashiyo, And they love it. And then they could play this thing, and were happy playing—you know, playing the bass with the plectrum, so you feel the sound can hear the sound pounding inside the stomach. You know, that typical mbaqanga sound. So I wanted also to make it up project to approach the arts and culture to help me rubber stamp, because this is the accent of the typical Southern African music, to really make this musical our pride. Just like reggae rubber-stamps Jamaica.

Good for you. It is such a pleasure to hear that. Especially that you're doing this with young people who really didn't grow up with this. They are doing a great job. Playing the bass with a plectrum like Joseph Makwela.

Like Joseph Makwela, yes. And the guitar like Marks Mankwane.

Marks! Of course. But you have a cello in there too. Tell me about that.

Yes, we have a cello in there. So we are supposed to start the show very subtle, just me and acoustic and followed by the cello, and then the badge. Most people love me just Vusi Mahlasela, just me solo and my acoustic guitar. So the accent of my voice and acoustic guitar. But before we started the show, there was a program with the recording facility. The sound engineer was very much freaking out. And I was like, “No. Take it easy and you'll be O.K.” So we started without the band and the cello guy was supposed to accompany me so we do a buildup. But he fitted so very well even with the mbaqanga. Because on some of my songs, I had violin, especially on one song by Noise Kanyile, from Durban. So that's sound of the cello and the guitars, that's a very organic. And no keys. No keyboards.

Oh, I love that. I've always been a guitar guy. I feel like keyboards have messed up a lot of nice African music. So you made a good choice there in my book.

I made a tour with Hugh Masekela. We were celebrating 20 years of our freedom, And we ended up at Carnegie Hall. So I told brother Hugh, "Please, no keys." And he said, "What?" I said, "No. No keys. We are just going to have guitar, percussion, bass, drums, and then me acoustic, and then your trumpet. No, please, no keys." And we did a tour like that with no keys. People loved it.

That's fascinating. We were there. We loved that concert.

And brother Hugh said to me, "If anything, talking about the Graceland tour, this is the one. This is the real one." He was so happy. He enjoyed the sound. And this is why I'm so typical in just liking the sound of guitars, and not too much keys.

Let's talk about the songs. Let’s start with “Umculo.”

“Umculo” is a Zulu word meaning “music.” So the lyrics are, "Music takes away the boredom. The music was here before we were born. And the music is still here. When you have music, even work goes smoothly. Music takes away the boredom.” And the typical sound of “Umculo” is the mbaqanga feel.

Is that an old song?

It's an old song was recorded by the Mahotella Queens, with sister Hilda Tloubatla.

Funny you should mention Hilda. I have a big picture of her over my desk here. She is my inspiration as I work every day. I love her. What about “Khona Manje.”?

“Khona Manje” is a gospel song. It's a typical South African gospel song with the taste of mbaqanga, because it's got those rifts as well. “Khona manje” means "right now." It's a Zulu word. So it is saying that you have to receive Jesus right now. Don't waste time. This is the time to receive Jesus. Right now.

What about “Intombi.”

“Intombi” means "a girl”—a young girl, a beautiful girl. This is a song that is coming from my father's side. I was raised by Mahlaselas, my mother's side. So my father's side, the last name is Zwani, from Swaziland. So my father together with his brothers, my uncles, they were singing this typical mbube and other music. And this is their song. This is one of their compositions that they were singing, and that they would go to those competitions, just like Ladysmith Black Mambazo. The competition will start from around five until the next morning, and the winner would win a gold [prize] and so on. My father and my brothers, they loved this mbube type of music, and this is their song that I took from them. So I put it on the album.

What about “Molaetsa Keo”?

“Molaetsa Keo.” It means “a message there.” It means. “There is a message.” It’s a Setswana song. This song is about land and food security. Because our people there are so close to famine. How can I have more land so that I can farm? I must have more food for my family, and so on. So this was written by the Dark City Sisters. It's about land and food security. So the message also at the back is saying, "Where lies the dignity of man if he doesn't have land, a place to stay, a home, or a job?" So this addresses all of that.

What about the first track, “Imal’ Iyaphela”?

“Imal’ Iyaphela” is my own composition. Imal is money. The title means money got finished. The money is gone. So here it says, if you spend money very badly, if you have a million and you buy a loaf of bread, it's no longer a million. So you must use your money wisely. Money is like alcohol. If you spend it wrong you will go crazy. So that's what the lyrics are saying. So got humor in it, but it's also telling those people who are really ravishing, while spending and spending and spending. So “Imal’ Iyaphela.” The money is gone. You had it today, then it's gone. Because you couldn't manage it very well.

That is a timeless message, good for everyone. What about “Ithemba Lami,” another mbaqanga number.

“Ithemba Lami,” it means “My hope.” This man was singing about his lover that was his hope. I think the woman was about to leave, and he was just pleading, “Itehmba Lami. You are my only hope. You cannot, please, leave.” I know I heard this song when I was growing up. They were playing it in the shebeen. But I don't know who was the composer. So we just put it as traditional. Until we can find the real author.

Good for you. I spent a lot of time in Zimbabwe. I hear little bit of Oliver Mtukudzi in that song.

Yes, the style. I've borrowed the chimurenga guitar style.

Well, it's a beautiful album. I hope someday you get to bring that group here to perform. We would love to see that.

I'm looking forward. You know, these people were doing that music, like Mahlathini and the Mahotella Queens, they were the ones who were exporting our culture and our music to that side. So we want to bring it, because now they are old, and I want these young guys to be able to revive this and bring it. So we are coming, definitely, because people love it on that side.

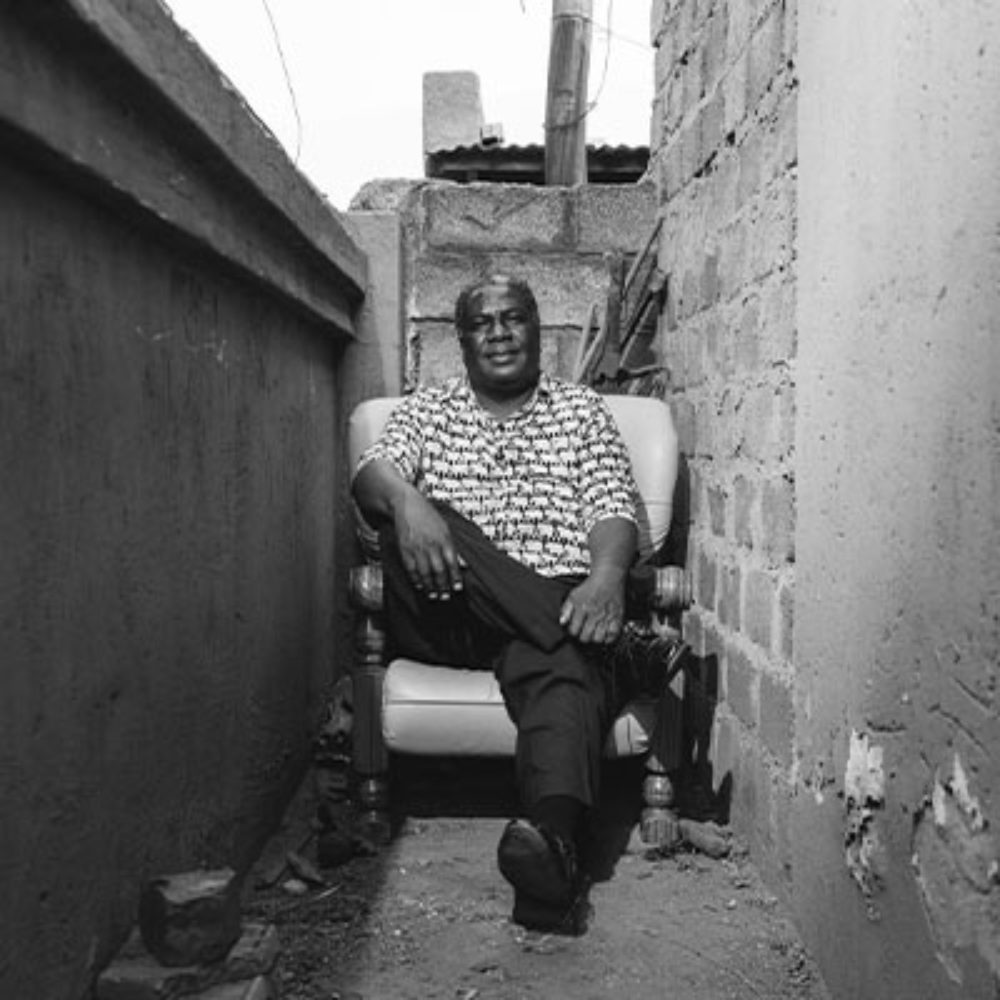

So true. We started in 1988, and those were some of the people that inspired us. I have to ask you about the promo picture for this album when you're sitting in an easy chair in a very narrow space between two buildings. What's going on there?

That was at my grandmother's place, in the backyard. So there’s the original house, and also the other rooms that are built in the back. So that is the space in between the two walls. But that space there, it is sacred—a sacred space, I must tell you. That's why a put the chair there. Because that's where we would go and pray to our ancestors. And something just said because I was dedicating this thing to my grandmother, I had to sit there.

And I see you've included one of your classic songs, “Silang Mabele,” such a beautiful song.

It's also again about food security and about the land. But it's also about creating awareness, to encourage the agricultural revolution. It's a call for unity to fight poverty all over. Silang mabele, it means "grinding the corn."

And then you have this very interesting instrumental song. It seems to touch on a lot of styles. “Draaikies.” That's an Afrikaans word, isn't it?

Yes. That is an Afrikaans word. You know, what you go in draaikies, you go in corners, in circles. Draaikies means "in circles." This is Philip Tabane’s song, and then there's "Zimbabwe." That's also a composition that I have written with some of my friends, Dr. Lance Nawa and Mongezi Chris Ntaka. So, Zimbabwe, it was more encouraging the Zimbabweans to go back and build their country again. So that Zimbabwe should become the food basket of Africa again.

Good for you. I spent a lot of time in Zimbabwe. I hear little bit of Oliver Mtukudzi in that song.

Yes, the style. I've borrowed the chimurenga guitar style.

Well, it's a beautiful album. I hope someday you get to bring that group here to perform. We would love to see that.

I'm looking forward. You know, these people were doing that music, like Mahlathini and the Mahotella Queens, they were the ones who were exporting our culture and our music to that side. So we want to bring it, because now they are old, and I want these young guys to be able to revive this and bring it. So we are coming, definitely, because people love it on that side.

So true. We started in 1988, and those were some of the people that inspired us. I have to ask you about the promo picture for this album when you're sitting in an easy chair in a very narrow space between two buildings. What's going on there?

That was at my grandmother's place, in the backyard. So there’s the original house, and also the other rooms that are built in the back. So that is the space in between the two walls. But that space there, it is sacred—a sacred space, I must tell you. That's why a put the chair there. Because that's where we would go and pray to our ancestors. And something just said because I was dedicating this thing to my grandmother, I had to sit there.

Fascinating. Zoom is about to cut us off, but in the little time we have left, how are you getting on in the midst of this pandemic?

Well, I am just trying to be positive, man. It's all in the mind. I'm trying to be positive and be strong. I've had some health challenges as well, but I'm getting better. I'm just telling myself, "No, this is something that will come to pass." It is been quite a lot of frustration, but through this lockdown, I'm happy that the album is being released. Because it was recorded in 2018. So now to finally be released, I'm happy. And it got a good review in the New York Times.

I'm not surprised. It's a fantastic album.

I've been working also, quite a lot, writing a bio. I've been organizing with other writers. It's going to be called Culture Against Apartheid: From Colonialism to Post-Apartheid. And then I have my story, which is A Soldier of Peace Against Apartheid. And I will also be doing a bio and an audiobook as well. And lastly, I'm looking forward to recording my solo album, just me and acoustic guitar.

Well, it sounds like you're making very good use of your time off the road. So good to talk to you, Vusi. And thank you very much for this album. It gives us great spirit in a hard time.

Thank you very much.

We look forward to seeing you down the road.

I promise!

Related Audio Programs