On Sept. 11, 2001, Sean Barlow and I stood on a Brooklyn rooftop and stared slack-jawed across the Hudson, knowing that our world and lives were being forever changed, right before our eyes. Twenty years later, we returned to Brooklyn after over a year of Covid-based exile to see arguably the biggest star in today’s African music make his debut solo concert in New York at what has to have been a hugely successful benefit for Celebrate Brooklyn and BRIC Arts. How do these things relate? At first blush, they don’t. And yet each is a reminder of how just how much the world has changed in these 20 years.

Ayodeji Ibrahim Balogun, AKA Wizkid, was 11 years old in Lagos on 911. He was growing up in a poor neighborhood, which he would later immortalize in his 2015 song “Ojuelegba.” With single minded focus, Starboy, as he was sometimes known, came up fast in a burgeoning Nigerian music and film industry that was in its infancy in the early 2000s. As the crowd gathered in Prospect Park, Wizkid was riding an unprecedented tsunami of global African music popularity that rises under the banner of Afrobeats, and shows no sign of slowing.

Having failed to secure an interview with the artist, I decided to interview his fans, who arrived in their thousands, most of them Nigerian-American women in their 20s or early 30s, over the moon about what was about to unfold. I began by asking, “What do you love about Wizkid?” but after one too many smart replies of “his music,” I amended the question to “What do you love about Wizkid’s music?”

The answers were varied and passionate: his vibe, his versatility, his honesty. A number of fans cited his “spirituality,” perhaps a reference to Wizkid’s Christian-Islamic upbringing, though it seemed more about some ineffable quality in his music, not immediately apparent in lyrics like “I want your body sleeping in my bed.” O.K., this is not the African music I grew up with, and no matter how many Wizkid shows I see, or how many of his fans pour out their hearts to me, I can never fully share their experience, any more than they can experience my ecstatic response to seeing Mahlathini and the Mahotella Queens make their U.S. debut in 1989 in front of an audience a small fraction of this one’s size.

For me, the true star on Saturday night was that audience. For starters, every one of them had to prove they were double vaccinated to gain entry, which puts them well ahead of a quarter of the country in the wisdom department. Beyond that, many I spoke with cited Wizkid’s impact in uniting the global African diaspora and raising awareness of its connections to American and world popular culture. Their feeling for the man and his music was profound, thoughtful and brimming with the thrill of a new era dawning for Africans in the world. I had wondered whether this show would provide evidence that Afrobeats was truly crossing over into the American mainstream. It did not. Instead, it indicated vital solidarity in an American-African diasporic demographic that is undeniably a growing force to be reckoned with in our American cultural tapestry.

There were no seats at the venue that night, so folks were packed in tight, nearly filling the open space before the stage at what has to be New York’s most scenic and enjoyable outdoor music venue. The show began with Wizkid’s personal DJ, DJ Tunez, who spun a compelling mix of Afrobeats, pop and reggae, exhorting the crowd at one point to joyously sing along to Wizkid hits. Wizkid was slated to come on at 9:15, but did not hit the stage until some 25 minutes later, and given the show’s hard ending, that meant we heard a lot more from DJ Tunez than from Wizkid himself. The energy dipped a little by the fourth or fifth false alarm that the star was about to take the stage.

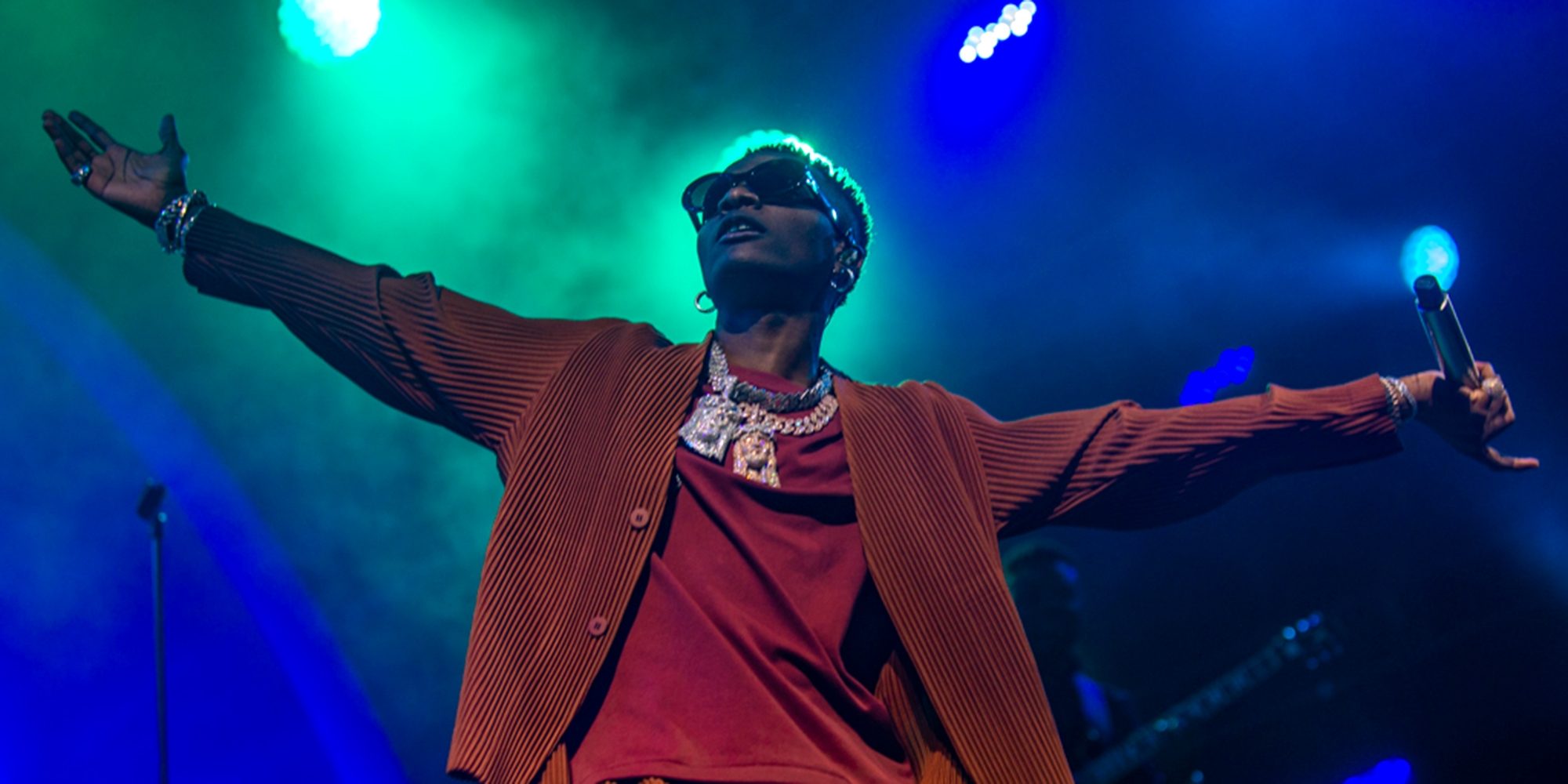

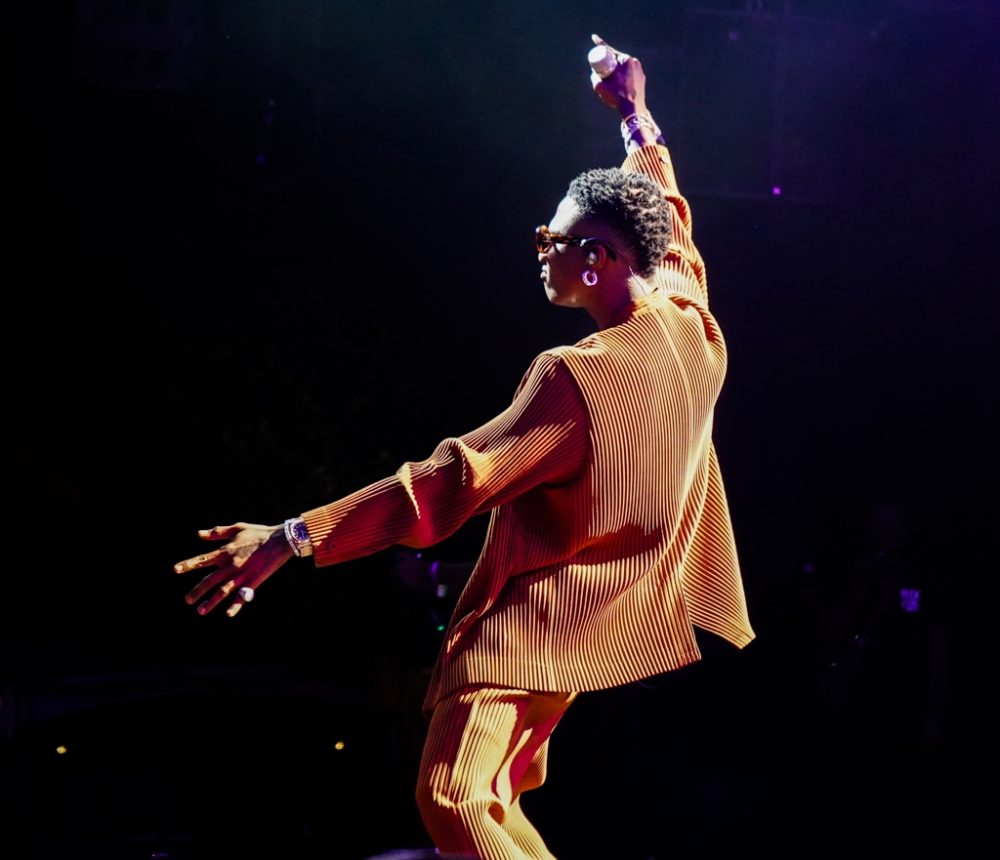

But none of that mattered when he did appear, lanky, loose, bejeweled, and ready to party. Wizkid’s moves are large, fluid and playful, all nicely complemented here by his baggy, peach-colored outfit. You really can’t take your eyes off the man, as he owns every corner of the stage. The music came across as more driving and forceful than on his four albums. Songs that play as suave neo-soul in recordings pounded forth boosted by mega bass throb and sharp backing from Wizkid’s live band—guitar, bass, drums, keys and, of course, DJ Tunez. Wizkid’s 2020 album Made in Lagos, produced the hit “Essence,” the first Nigerian song to make the Billboard Hot 100. I had asked fans for a favorite song, and a few cited “Essence,” particularly the remix featuring Justin Bieber. But there was no broad agreement; every fan had his or her pick.

Not too many of those songs made it into in Wizkid’s seamless, fast-moving set, but no one was complaining. When the show ended abruptly around 10:30, the crowd swept peacefully off the grounds in a mellow river of blissful humanity.

Meanwhile, the light towers at the 911 Memorial soared into the late summer sky, barely noticed, but for many of us, an annual reminder of all the ways our world has changed. Twenty years ago, an African star filling a such a large New York venue with young diaspora Africans would have been unimaginable, a welcome reminder that some of those changes have been for the good.