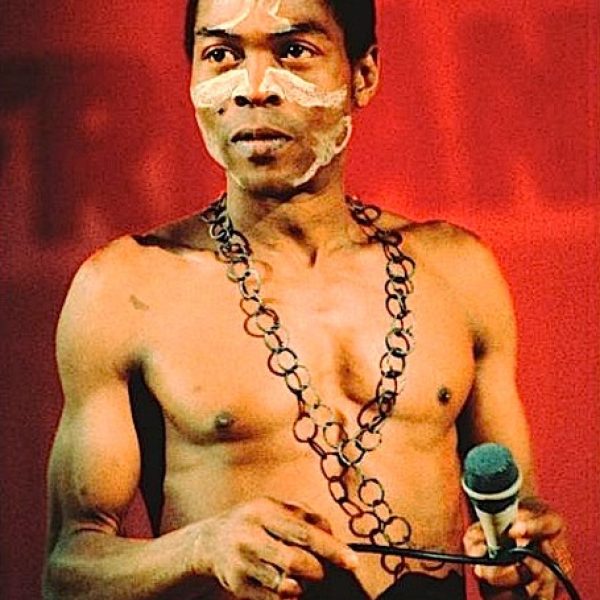

Femi Kuti burst on the scene over 20 years ago as the new face of Afrobeat—youthful, vigorous, and ready to carry forth his father’s august legacy of innovative, hard-driving big band grooves and no-holds-barred peoples’ politics. Now with his seventh studio album, One People One World (Knitting Factory), Femi has mellowed some, grown significantly as a musician and become himself a kind of elder statesman, ushering his own son into the Afrobeat fold. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Femi by Skype in Lagos to discuss the new work and more. Here’s their conversation. (Photos by Banning Eyre)

Banning Eyre: Femi, good to hear your voice. The last time we saw you was about a year ago backstage at the Shrine when Afropop was there doing research for our series on Nigeria. It was a treat to see you rehearsing at the Shrine. I've been enjoying the new album, so let's start there. The press release describes the sound as "back to roots." How do you see the musical evolution of your band Positive Force on this album?

Femi Kuti: I'll just say it's just music coming directly from within me, because I don’t listen to anything anymore. I hear the melody. I want my music to be as pure as possible, coming from within me. So I would say this is just me in my essence.

Would you say that is a product of all the things you've listened to over the years?

I would not even say it's really what I listened to, because if what I was listening to or what I've listened to, then it would really reflect a lot of jazz or else my father. It's very hard to describe. But I know that I've just let these melodies and rhythms flow inside me. I was very involved with my father's work. I listened to a lot of jazz and a lot of old soul. I probably would be listening to Miles Davis or Coltrane and become inspired. Now, the way I get inspired is just by either practicing or just looking around me in day-to-day life. So it's not like I'm inspired by an album I listened to, or going to watch my father play or something like this. I think it's my spirit in its essence, like I said.

I see. But you say it begins with a melody. That's usually your starting point right?

Yes.

You have a very distinct sound, and that's a real achievement given your connection to Afrobeat music. We've talked in the past about what it's like being under the mantle of your father and I think you've managed to take all of that and make a sound that's really your own. You hear a Femi Kuti song, and you know right away who it is.

Thank you. That's great to hear.

Has your band changed much over the years? Or is it really pretty much the same personnel that you've had?

It's basically the same. At least 70 percent of them have been with me for 13 to 15 years. Those that are newer have been around for at least six years.

The press release for your new album highlights your guitarist, Owomolo. Is he one of those veterans?

Yes.

He's got a great sound. Let’s talk about the overall character of the album. There's a more sort of optimistic, upbeat songs here, in terms of lyrics. There's also plenty of politics, and we'll get to that in a minute. But I want to talk about the sort of down home, peaceful, loving side of this record. What would you say about that?

It's where I am right now. I think over the years with age, maturity, experience, I've been able to start to find peace within myself. There's so much chaos and global suffering and unhappiness, I've had to dig deep to find sweet melodies or good energy to give myself and people that listen to my music, to uplift their spirit and souls. Because there are so many things that are depressing, I didn't want to bring out another depressing or sorrowful sound. So it was like digging deep to find good energy. Hopefully, we believe that when people hear this melody, it will inspire them to think positively and find the energy to go out and hustle and survive.

I guess there's always been an element of that in your sound. I mean, the band has been called Positive Force right from the beginning. But what songs would you point to here that show this new impulse in your songwriting?

"Best to Live on the Good Side." "Africa Will Be Great Again." "One People, One World." Basically, even when the lyrics are even quite sad, like “Evil People,” the music is very powerful, very dynamic.

The song "Africa Will Be Great Again" has a refrain that always starts with "can you believe…" You're looking back to times when things were better and you're basically imagining if it was like that then, why can't it be like that again?

Yes, it's saying that things were different. Of course, it was bad then because my father was complaining. But if it was that bad then and my father was complaining, how did it get so much worse now? What I'm saying is, I truly believe we can turn things around. We have no reason not to be able to turn things around. It's really to motivate young people. Especially when I'm playing at The Shrine, I use my age as an example. When my father was speaking, I was 9, 10, 11. I'm 55 now. We're saying the same things, it's getting worse but we're still surviving. I don't know how we still managed to go on living day to day, but why can't Africa be the envy of the world? So I’m trying to project a positive future. It was bad then, as my father was telling us. but compared to today it was good. Today it's really a disaster.

You think it's worse now than then?

Yes, definitely. Look at the economy. In those days the dollar was $2 to one naira, which is our currency. Now it's over 400 naira to the dollar! So if you look at it economically, it's 400 times worse than it was then.

I see.

People can’t afford good education. They can't afford to pay their rent. They can’t afford health care, so you can go on and on with this.

I want to ask about the song "In Dey the Body."

It’s a bonus track. That one has a very powerful horn section.

It also has powerful words. You talk about Jonathan and Buhari, the former and current presidents, by name. Can you name names like that and not fear reprisal or problems?

If we think about the problems, we probably won't do what we have to do, so I don't think about that. Over the years I've made people know where I stand. I don't say what I say to annoy anybody. I just speak the truth. That's the way see it. And people know me for this. For instance, when The Shrine was built, everybody thought it was a place to be antagonistic. And it took a long to explain we're not being antagonistic. And this is the same misconception they had about my father. When we're speaking about problems, it's because we love our country and we want it to be better. So people should stop misinterpreting when we are complaining of, for example, no electricity, and we are comparing. Africa can be the envy of the world. We can have a railway from Lagos to Johannesburg. There's no reason why we can't do that.

Let's talk about The Shrine for a moment. I went there three or four times during the month we spent in Nigeria last year. It's such an incredible environment there. It's a space that really feels like its own subculture—very powerful and beautiful. I did hear people—music fans—saying they weren't happy with the sound. They felt it was too echo-y and you needed to get better equipment. What's your take on The Shrine and how it's doing after the many years it's been operating? And what is your sort of vision of its future?

Concerning the sound, yes, some people complain about the outdated equipment, but then they have to remember that everything there is free, so they have to make do with what they have. Where do they believe we're getting the money to give them a full concert two times a week? The disco is free. Everything is so cheap. Because we understand the plights of people, I mean if they want good sound without echo and all that, they are going to have to pay. Now, they can't afford to pay so we don't want to go begging, so we're making do with what we have. And it's taken us 18 years at the Shrine.

Eighteen?

Yes, 18 years in October. So it's taken so much energy. I've used all my coins I make from my tours for a good 10 years, I had to use my profession, my tours, to build The Shrine and get it to where it is today. Because at first, The Shrine couldn't fund itself. Today, it can fund itself, but at the beginning, I had to use all my income to keep it at the level we wanted it. It's still not where we want it. But considering that it's free, I mean we can't do better than we do right now.

That makes sense.

If I do get some big money from somewhere, of course I'm going to invest it. I would love to build a big studio. And I would get more equipment and make it better, of course. But people have to understand, we are doing this because we want to help our people.

And that definitely comes across. I know that you like to rehearse there. I spoke with your brother Seun, and he told me he does not like to rehearse at The Shrine. I find that interesting. I know your father rehearsed there. I had interesting interviews with people who remember being kids and going to the old Shrine and having your father call them out from the stage, "You kids get out of here. Go back to school." Things like that. But you like to rehearse in that public mode, with the people there. Talk about that. What does that do for you?

I have always done that, most of my life. So I love to psych people's reactions when I start. It's like painting. So you start to paint, and by their reactions, I can know whether to make a color deeper or lighter, or what direction I want to go. And I will start a number and it changes. After about a year, it changes drastically many times. So by the time we take it to the studio, it's very different. This is because of the reaction, the feedback I get, just watching the reaction of people listening to the number. I might not really like a number, and people think it's great. And then I can start to proceed or process that number for them. So it's not a personal ambition anymore, so to say. If it is a song I feel very sentimental about, then I try to make people feel what I'm feeling. So there are many ways I could get direction that helps me finish the song.

And of course, I still work privately. I play at night at home. I will rewind all those vibes in my mind. And I can make all those corrections before I present it again, and again, and again.

It's like a feedback loop. We spoke with Fela’s manager Rikky Stein for our series, and he said an interesting thing about the way your father worked, rehearsing in front of the audience like that, and reading them, just like you are saying. Rikky thought that was really one of the secrets to Fela’s incredibly powerful connection with people. It was his ability to gauge that reaction. Rikky said that no opinion meant more to him than the opinion of those people who came to watch him rehearse at The Shrine. So let me ask you about having your son involved in this record. The next generation of Kutis. Tell me about your son Made.

Oh, that was so powerful. That was probably the most beautiful part of this recording. He played the bass, piano, and it was really incredible. So beautiful. It's hard to explain, but it was really touching. It's very important for me, because he can feel firsthand the way his father works, and he has been a very big part of my life. At every stop, or at every opportunity I can get him to get him into my mind. This is very important, because one day, I will not be around, and I want him to have all my experience, and all the information I can give him, musically, on life, to help him develop. And to take this music to another level, especially with his education. So he has everything at his disposal to give people good music.

How old is he?

He will be 22 this year. He comes out of university. He's going to finish. He was born in 1995.

It's so interesting the way fathers and sons work in music. I have this question. What did you learn from your relationship with Fela that is guiding you in your raising of Made?

Ahhhh. [Long pause] Probably what I learned most is an ability to be lovable, especially in public. It's very hard. An ability for him to be confidential with me. Or intimate. Like, he studied music. He can read and write music, so there's no reason why I should not be able to read and write music. So I have struggled all my life to have the basic foundation and be a musician. Everything I've learned has been hard work on my own. And he believes this was my power to distinguish myself. He might be right. Probably without that my music would be boring. I had to find so many different energies, different ways to find a way to survive as a musician. So I see where he's coming from, but I don't think I would want any of my children to go through that emotional torture.

So my son can read music beautifully. He can read anything. He can play anything musically. But I always want him to go into my mind. He has the ability. He has been privileged to hear things I probably would not discuss with anybody, but I discuss with him. The way my mind functions. So he knows everything I probably would not like to discuss in public about my life with my father. I would discuss with him, so he knows all the intimate things I had with my father. That I would share with him on his own to make him a better musician. Because now he has his life; he has information from his grandfather; and he has information from me, and he has beautiful brothers and sisters. So it's going to be a complete. I think he has the ability to change the music, Afrobeat, into something completely different.

Just as you have.

I don't want him to be me. He has to be himself. I want people to appreciate him. Of course they will see me in him, but if he copies me, there is nothing new. So he has to go to another dimension that will make us all go, "Wow. This is beautiful."

And speaking of other dimensions, you are now operating in an environment that we saw very vividly, where this whole new wave of music that is being called Afrobeats is surging and taking over and having this incredible success. What is it like operating in this new environment, and also, how do you feel that they appropriated the name Afrobeat to call this new music Afrobeats?

Well, I can't be too critical of them. They are young. I can merely advise them that they better pick up a musical instrument or by the time they get to my age, they will all become irrelevant.

Amen.

My advice to them is they have to pick up an instrument. They have to be able to extend to improvisation, or else another generation will always come by and be more daring, more everything. They will have their own fan base. The reason why I can do as I choose is that a generation came up to appreciate and respect what we do with our musical instruments. Even my father, he could read, he could write. He could play all the instruments. He knew what he was doing. Now if you're going on your computer and just playing with sounds, you don't even know musical notes or have an idea, how long are you going to succeed? It's like a doctor who doesn't take the time to learn medicine. Sometimes you will be right. Sometimes you will be wrong.

Music is as serious as studying medicine. Engineering. Or being a pilot. It's serious business. It's not just about fame and fortune. A lot of people need to understand this before it's too late, or they will be in big trouble when they get old. In my time, I picked up the trumpet. When I got bored with the sax, I picked up the trumpet. I decided to teach myself the piano. The trumpet takes up a lot of my time now. I really want to be a great trumpeter. And I sit for six hours of practice every day. You have to be willing to develop yourself. It's like the doctor has to keep reading books about new medicine, to help his or her patients. It's very important. So it's a sacrifice you have to make for your base, for your fan base.

Because when people come to listen to or watch you, they want you to help them with their pain. So for young people, yes, it's all right. I even like a lot of what they are doing, but I just fear for the future.

Speaking of playing instruments, I was very impressed last May when you broke Kenny G's record for playing the longest note on the saxophone. I'd like to hear the story of that. Was that something you set out to do intentionally?

Yes. A long time ago. Because I thought it was 46 seconds. And I used to do it, actually. I couldn't understand why everybody was making so much noise. Because I could play for three minutes or five minutes. And then one day, I heard that it was 46 minutes! I couldn't get past 10 minutes, so I gave up hope long time ago. I said I would just enjoy myself with this ability to do what I could. And then one day at The Shrine, two weeks before making the record, I saw I got up to 40 minutes. And I told my sister, "Wow. That was so close. I thought it was impossible. During next week, I'm going to break the record.”

My sister is very proud of me, so she went posting everywhere. Call the TV. Call the radio. So everybody got there. I did break the record, but apparently there's another record out at 47 minutes. Somebody from Australia. And apparently, he didn't want to make any noise, because he loves Kenny G. So when I broke Kenny G’s, the next morning there was, "No! Fake news. Fake news. There's another record." So this was very hard work for everyone at The Shrine, including myself. So I said next week, I'm going to break the record.

Of course the Shrine was now jam packed. And I got to 51 minutes 35 seconds. So apparently there is another record at 50 minutes. So I shattered everything. It was the happiest day of my life. It was beautiful. I could sleep. And now, any time people say, "Oh, break the record again," I say, “For what? It's Kenny G's record. Don't you see the beauty of what I'm doing? Why do we have to be in competition?"

They say, "No. Kenny G did it."

"Shut up your mouth, O.K.?" So now, everybody can relax.

That's a tough game. Congratulations. I'm very impressed. I look forward to you coming back our way soon to promote this record.

We should be there in the summer.

Related Audio Programs