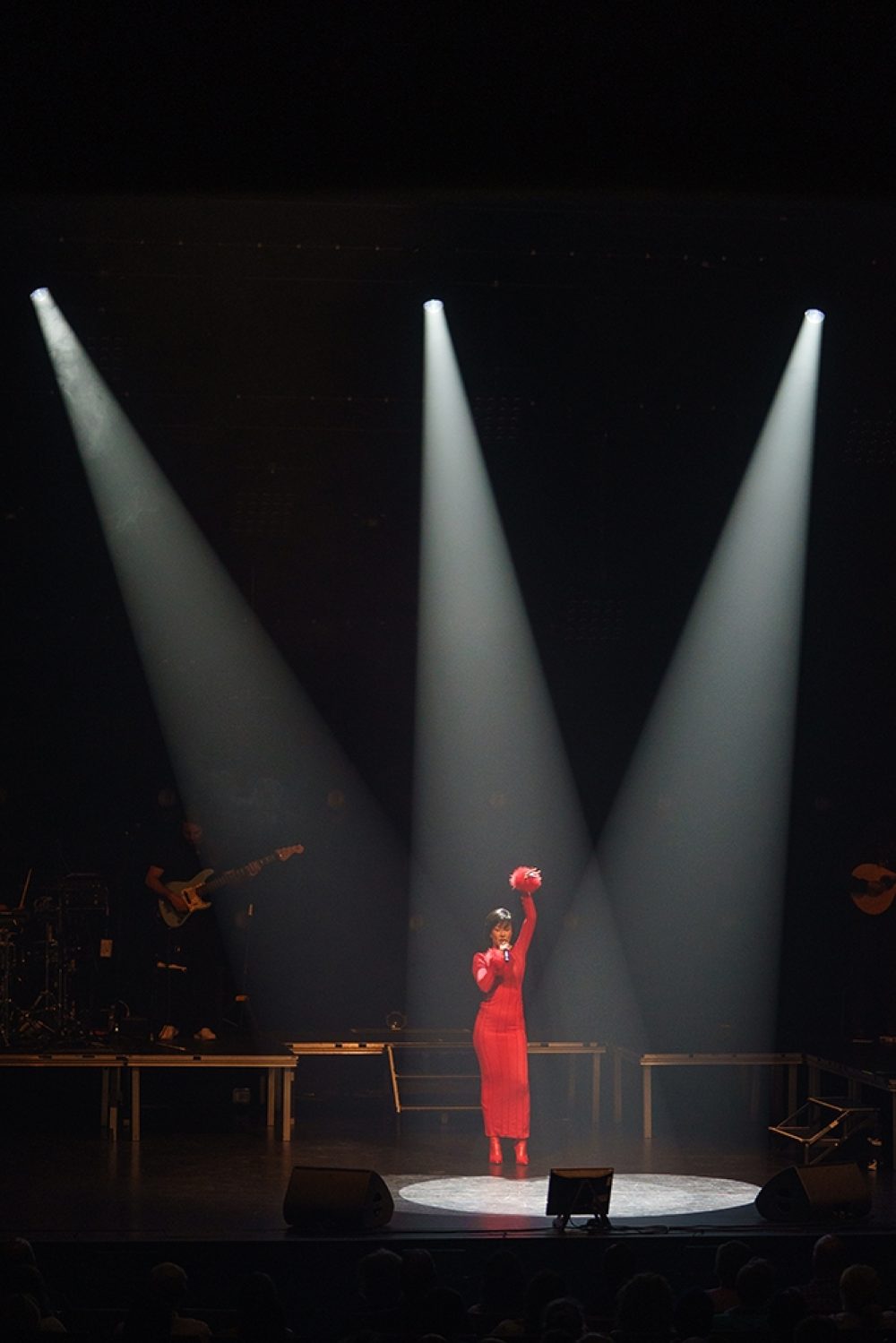

Banner photo by Benoit Rousseau

Born in Portugal, Ana Moura grew up in a home surrounded by all the country’s musical styles and those from its former African colonies of Angola and Cape Verde, as her mother's family had emigrated from Angola. As a child, she already knew her destiny was to be a singer. She studied music as a teenager and at 21 was signed to Universal Music and began production of a pop/rock album. But the album was never completed, as one night she was coerced by some friends to get up to sing a song at a fado house. What none of them knew was that famed fado guitarist Antonio Parreria was in attendance. He was so impressed with her voice that he took her around and introduced her to the fado inner circle. And so she became a fadista.

Fado, actually means “fate” or “destiny,” and began to appear at the turn of the 20th century in dive bars frequented by sailors and prostitutes. The music expresses the untranslatable emotion of “saudade,” a melancholic and longing for some peace in a world of sadness and struggle. Starting in 2003, Moura released three fado albums over the next few years which grew her celebrity and soon she was crowned the new voice of fado. In 2005, she performed at Carnegie Hall extending her fame across the Atlantic. And over the next few years, she found herself on stage singing with the likes of the Rolling Stones, Prince and Gilberto Gil.

Jumping forward a decade, she had been in the midst of producing a new album and readying a world tour in 2019, when Moura was struck with her own deep “saudade.” The constant touring and recording was exhausting her. She walked away from both her label and management. But as someone not inclined to despair, she set to work on herself, on a journey of discovery which led her to the small dance clubs in Lisbon. There, she was inspired by what some young producers and musicians were doing. And when the pandemic hit, she called some of these new friends up and invited them to spend the pandemic with her and record a new album. What resulted, her 2022 release, Casa Guilhermina, is a major departure – going both back in time to her African heritage, and taking her music forward with modern beats and electronics. Much like what Rosalia has done for flamenco, Moura is reinventing fado for our time.

We were fortunate to be able to sit down with Moura for a conversation before her well-received concert at this year's Montreal Jazz Festival. The interview has been edited for both clarity and length.

Ron Deutsch: First things, first... How are you?

Ana Moura: I'm good, I'm a little bit tired because I was in Portugal last week recording a new video, a very tough video because I am dancing now through my music. That's a very new thing. But because I grew up listening to African music, music from Angola, it was very common in my family to dance. But yeah, in fado, we don't dance. Actually, in the 19th century, people used to dance fado – and with their hips. But that was lost along the years. So last week I was shooting this video, and it was really intense because I had to learn all this choreography. Then I flew right to Canada. So I'm a little bit struggling with the jet lag and all these kinds of things.

The video is for a new song, just a single I'm releasing soon. I think that to do an album nowadays we need a period of time to dedicate to it. But sometimes you just want to write a song and sing it, you know? And to me, it makes sense to release one single, once in a while.

I was thinking about how fado is kind of an intimate music. You go into a small bar, there's someone singing in the corner or something like that, a little stage area. And the music itself is so emotional – being so close to the source – it's a very intimate experience for both singer and listener. So is it different when you're on a big stage like here at the Theatre Maisonneuve, trying to connect with well over 1000 people?

I think it's more that nowadays it's difficult for me to sing for a small group of people, you know? I started like that in those traditional small fado houses, but yeah, that proximity now, these days, it's a little bit more complicated for me to be honest.

Why do you think that is?

I don't know. Maybe, because the stage, actually, the big houses, there's a distance. There's two spaces, you know, that coexist in the same room – the stage and there's the audience. And in those traditional small fado houses, we're in the middle of the people. It's intense because people are very close and really seeing everything – the way we breathe – it's a little bit more intense because of that.

Were you fine with that when you started out or was that still kind of weird for you?

[Laughs] When I started, it was weird for me. I was very shy. I'm still a shy person, but at the time I was very shy. And I remember we would be doing this in circles, so everyone could see our face when we were singing. And each fado singer would sing three songs. I couldn't move myself, so I would sing the first fado to this side, the second one to this side, you know, because I was so afraid to fail. I was so shy.

Before we began the interview, you were telling me that some historians now believe fado comes from Africa.

Yes, yes. There are many people that say this, but then the Portuguese went to Brazil and we absorbed that also. And Portugal before being Portugal, it was Moorish for centuries. And there are people that say it sounds like Arabic song. So it's normal that fado has all these influences. But still, the way the country is placed, for example, with the sea and Europe in our back, it makes our personalities, we are – how can I say – with all this immensity, it makes us more moody. And we can see and feel all that in fado.

Nowadays, it's very interesting, because Lisbon is small, but has a lot of culture now in the city. Especially the children whose parents came from Africa, they are placed in the suburbs of Lisbon. And there's a specific type of music now in Lisbon that's African, but it's called “Batida de Lisboa.” It's very interesting because it became Portuguese, because it was born in Portugal through the children of the African diaspora. It's electronic, but with African rhythms, but also with this kind of soul that I was trying to describe that the Portuguese have – you know, that makes us a little bit more melancholic – that was the word that I wanted to say before.

And now you've introduced these musical styles like kizomba and kuduro in your last album, “Casa Guilhermina.”

So I grew up listening to Bonga, Paulo Flores, and naturally, it's present in what I do musically. So not only in this album, to be honest, but it was also there in the previous ones, but more subtle. Now I'm actually bringing in some musicians who play African music, specifically kizomba and samba. This album has all these flavors. So yes, samba, kizomba, fado, obviously, and I also have folklore from the north of Portugal. So I mix the rhythms of the folklore with the rhythms of Angola. I try to blend all of that because I am all of that.

And because we have this connection with Cape Verde as well, I grew up listening to Tito Paris as well. I love morna. I've sung morna since I was six years old. My parents used to sing and to play because they both sing very well. And my father, he plays a guitar and drums. They never did it professionally, but yeah, around the house, parties.

Tell me about the relationship between morna and fado. They both sort of deal with the same emotion.

Yeah, they sing about the same emotions, it's the same. Actually Tito Paris says that morna comes from fado. I don't know what comes from where, but I heard once Tito Paris saying that. But yes, the cadencia, the cadence, the rhythm, it's the same. It's slower, the cadence tempo falls – it's like the the opposite of anticipated tempo. So that's the similarity also morna and fado.

So they're kind of like cousins.

Yeah, we can say that.

I want to ask about, if I may about the decision to make a big change in your career – you quit recording an album half-way and left your record label. Would you mind talking about that?

Yes, I lost where I was. I lost myself, yeah. Because I was, I was traveling, traveling, traveling all over the place and I was not absorbing anything, you know. I was giving, giving, giving. When people asked me: “What do you like?” I didn't know what to say. So I needed to stop, but I couldn't. So I had to really ask my manager at the time to please help me to find myself, and help me to say no to traveling and concerts. And, so yeah, I didn't stop but I lowered the intensity and that helped me a lot to discover these new musicians. Suddenly I discovered these parties, these African parties. Have you been to Lisbon?

Yes. I was there for WOMEX a couple of years ago.

Do you know B.Leza?

Yes, for sure. I went there.

So, yeah, it's an African club at the river. So there were these parties with these DJs and producers – the ones that I told you about from the suburbs of Lisbon – and I really immediately felt connected. “This is me!” And that's how everything started. I invited two producers to start creating with me.

So yes, let's talk more about Casa Guilhermina. It's named after your house which is named after your grandmother.

Right, there is this tradition in Portugal where we give names to the houses. And I was thinking, what's the name? What's the name for this house that I built with all my stories? And I realized that Guilhermina, the name of my grandma, was the best name to give it, because, you know, I think that everything I achieved as a woman in life, it is thanks to my grandma. To my mom as well, and aunts... a lot of women. They're very strong, but at the same time, very sweet – it's a difficult combination. I mean, not a very common combination, because usually strong people are more tougher. But my grandma, she did everything like she thought she should do it, you know? But she was always very, very sweet, and she had this way of dealing with people that made them feel comfortable even if she did the complete opposite thing they wanted her to do. And I think that was a very strong characteristic that I absorbed from her. And I'm very persistent, as well. When I want something, I really fight for it, you know?

And yeah, she also gave me this beautiful thing of being not only one thing. I remember being younger and I was like, "Oh, I have an African family.” And I was like, “Okay. Am I African or am I Portuguese?” At the beginning, I realized, “Okay, I'm these two things.” I remember this feeling of belonging to something else and unsure where should I place myself. But later, I discovered that was the richest thing that I could have in my life. Not being only one thing, but being a lot of things. And not only through this African heritage, but through the whole world.

Then later, I became one of the main faces of Portuguese fado, the symbol of Portuguese. And so when I came out with this album, people were like, “No! No, you are Portuguese! You're not....” There was this shift, you know? It was like now that I achieved this place, I can't be the other parts of me. So at the beginning, people were like, “I don't understand. You're a fado singer but now you're doing kizomba. No, it's not for you.” I heard that – “it's not for you.” But then, they started to listen, and a lot of people that at the beginning were like this, then they understood and now they enjoy the album. At the end, it was very, very well received.

You've talked about the struggle for Portuguese music to be more known and accepted globally. Are you seeing a change? Are your audiences changing?

Now I'm in a transition, so it's a little bit complicated. In Portugal, for example, I'm reaching a much younger generation. But with the previous albums, outside of Portugal, the audience was more of an older generation, And now, I am in a position, using more electronics, for example, where the people that used to listen to me are like,“Okay, what is this?”

I don't know how people will react tonight. But I was sharing with a friend this morning that I was very happy to get the opportunity yesterday to see some concerts at the festival, because this city is really open to everything and that made me feel really comfortable. Because sometimes I go to these places where they were used to listen to me singing fado, and now they see me dancing and this African influence and this is not what they're looking for. You know, people are not open to, you know, “let me see what this artist has to share with me.” But I was very happy to feel that people here are very open to whatever the artist is.

Whom did you see last night?

Yesterday I saw Georgia Anne Muldrew. She was fantastic. That was my special concert yesterday, because she's so experimental, and she really transcends herself. Sometimes you see an artist that has an incredible voice or whatever and you are amazed by that. But here is a combination of things that really touches me because she's an amazing singer but she doesn't use her voice like most people would do. She creates a new way of expressing herself and her music. And the way people were interested, I was like, that makes me feel my eyes shine.

Well, I hope people's eyes will shine for you tonight. Thank you so much, it was a pleasure to meet you.

It was very nice to meet you. Thank you.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles