It’s an arithmetic fact that the immigrant workforce who travel from developing countries into developed countries power their economies. What a shame, then, that populist politicians demonize their immigrant neighbors when they are so indispensable to their own well-being.

Filmmakers have long told us stories of domestic workers, who form a large part of this immigrant workforce worldwide. We could include Hollywood big-star confections like Spanglish with Adam Sandler and Maid in Manhattan with J-Lo, period dramas like The Help, two versions of Imitation of Life, as well as films dissecting class structure in developing countries, like Roma, which earned director Alfonso Cuaron a Best Director Oscar. The most crowd-pleasing storyline in many of these derives from the Cinderella myth. Not the case in our discussion today.

So, let’s set our sights on two films telling stories about domestic workers, Nikyatu Jusu’s Nanny (2022) and Ousmane Sembene’s seminal Black Girl (1966). Separated by 56 years, both concern a Senegalese woman who is hired by a wealthy white family in New York’s Upper East Side, for Nanny, and on the French Riviera for Black Girl.

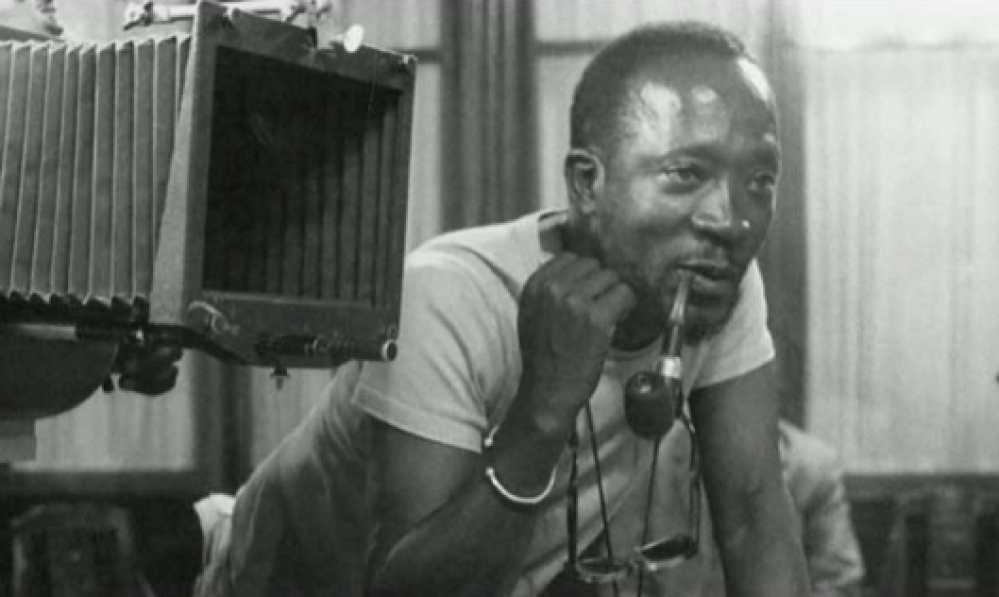

Ousmane Sembene has long been recognized as the father of African cinema. Before making films, he was also considered one of the greatest authors in Africa. In both mediums, he most often tackled controversial cultural and political subjects. Sembene in fact turned from novels to films because illiteracy was so widespread, he knew he could reach a wider audience, one not limited to the elites. Black Girl was adapted from “La Noire de…”, a story in his collection of short stories Voltaiques, and was based on a true story he had come across in the Nice-Matin newspaper, shown briefly in the film. It was very well received at numerous film festivals, winning the prestigious Jean Vigo Prize. Notable critic Jonathan Rosenbaum calls it “a masterpiece.” Martin Scorsese calls it “an astonishing film.”

Earlier, Sembene had been a dockworker in Marseille, a reader of Black authors from Haiti to Harlem, a member of the Communist Party, and a firebrand in strikes to halt shipments of weapons to support France’s colonial war against Vietnam. Later, he studied film at the Moscow Film School and worked at Gorky Studios. With this background, it’s really no surprise that Black Girl’s script was rejected by a film bureau in Senegal set up by France; and five years later his film Emitai was banned across all French West Africa.

The child of Sierra Leonian parents, Nikyatu Jusu was born in Atlanta, Georgia and has an MFA from NYU Film School, where she was awarded a Spike Lee Fellowship. Nanny won the Grand Jury Prize at last year’s Sundance Film Festival.

To call Black Girl minimal would be an understatement. A black-and-white film shot in old-school 4:3 aspect ratio, with natural lighting, mostly fixed camera, almost all non-professional actors, just a few pans, tilts and zooms, it features no crane shots or any costly techniques. It was shot with no sound recording, so the dialogue, often spoken offscreen or from behind the speaker, is entirely post-dubbed. Our protagonist, Diouna (played by Mbissine Thérèse Diop), is illiterate, understands French, but her on-screen dialogue is limited to sentences of just a word or two. Nearly all of her dialogue is in the form of a very emotion-laden voice-over narration. Sub-Saharan Africa’s first feature-length film, its limited funding made impossible any kind of elaborate production. Nonetheless, Sembene’s spare aesthetic choices are reminiscent of some of the earliest films by the French New Wave’s Jean-Luc Godard, as well as the most rigorous Italian postwar neorealist films such as Luchino Visconti’s La Terra Trema.

Nanny incorporates a supernatural theme alongside its social commentary, and, after a Sundance bidding war, Jusu got it released with the help of prolific executive producer Jason Blum, who produced both the Paranormal Activity franchise as well as Jordan Peele’s Get Out. Blum produced the first Paranormal Activity for $15,000 and it went on to become the most profitable movie in the history of motion pictures, so it’s worthy of note that Nanny was also produced on a shoestring budget.

Distributors of foreign-language media very often try to make translated versions more marketable to their audience with titles very different from the creators.’ Sembene’s short-story collection’s title, Voltaique, translates literally to “someone from Upper Volta” (present day Burkina Faso), but the English-language publisher twisted it into Tribal Scars, suggesting some kind of violence in a primitive land. Sembene’s short story we are discussing, as well as the film, were originally titled La Noire de… Tribal Scars’ publishers morphed that into The Promised Land, which is either deeply ironic, or--perish the thought--advertises the French Riviera as some kind of paradise for Black immigrant workers.

The re-titling of La Noire de… is telling. The original title La Noire de…, reflecting Sembene’s political views, is deeply subversive, and not about any kind of promised land. The French preposition de can only be interpreted as reflecting ownership, i.e., “the Black girl owned by…” There are two ways Sembene underlines this: First, the scene in which the white French woman hires Diouana resembles nothing so much as a market for enslaved persons where the white woman picks and chooses her from a group of Black women clamoring to be hired. Second, Sembene does not even give the white couple character names; they are just Madame (played by Anne-Marie Jelinek) and Monsieur (played by Robert Fontaine), which we can only interpret as Master and Mistress from back before 1848, when France abolished slavery. Sembene authored books when Senegal was France’s colony and made Black Girl only six short years after Senegal gained independence, so the issue of colonial oppression remained central to many of his books and films.

Both films are contemporaneous with when they were made, and Jusu succeeds skillfully in illustrating that not much has changed in how wealthy white people treat Black immigrant household help between 1966 and 2022. NY Times’ Manohla Dargis wrote that Jusu is “riffing” on Black Girl—not the only critic to compare the two films. Diouana is first hired to work purely to care for the couple’s three children in Dakar, Senegal, where Monsieur has some kind of post-colonial job, but when they move back to France, in Antibes, on the French Riviera, it proves to be a bait-and-switch; Diouna is relegated mostly to cooking and cleaning. Her earlier dreams of roaming glitzy Riviera spots are dashed, and she never leaves the apartment. Believing herself to be enlightened, the 2022 Mistress, Amy (played by Michelle Monaghan) gives her daughter’s new Black caregiver, Aisha (played by Anna Diop) a very awkward hug, right after handing her a binder jam-packed with her required Type-A job duties.

Much like J-Lo’s employer played by Tea Leoni in Spanglish, both Amy and Madame are extremely high strung. Amy becomes enraged when her daughter Rose (played by Rose Decker) hugely prefers Aisha’s tasty African creations over the Tupperwared, gluten-free, non-GMO, no-peanut, organic rations stacked in the Zero King. Madame, on the other hand, is just plain cruel; when Diouna, still in her Cote d’Azur glamor dreams, wears a pretty dress and high heels, Madame orders her to take off the shoes and angrily ties an apron around her waist, scolding her with, “Don’t forget that you are a maid!”

Men in both films treat the protagonists as sex objects. When 2022 Master Adam (played by Morgan Spector), revealed as a philanderer, is handing Aisha cash owed because Amy short-changed her, he lunges at her for a kiss on the lips. While serving lunch to Madame’s guests, one of them a heavyset, balding man whose character name is Old Male Guest (played by Raymond Lemeri), lunges at Diouna, kisses her on the cheeks, and brags, “I’ve never kissed a Black girl before!”

Remittances made by immigrant workers in developed countries to family members in home countries are very important. Despite Amy’s constant short-changing, Aisha dutifully sends money home; her son is under the care of a friend, and she plans to fly him to the United States soon. She is undocumented, unable to wire money, so she must send cash. Diouna, on the other hand, receives a letter from her mother asking why she never sends any money. Monsieur embarrasses her by reading it to her (due to her illiteracy) and pens a phony letter for her saying how she is having a lovely and fulfilling time in France. The situation is so bad for Aisha, she eventually refuses to take any money from Monsieur, and at the very end, even her mother rejects it when Monsieur brings the cash on his own back to Dakar.

I won’t give away spoilers, but tragedy intervenes at the end of both movies. Sembene rigorously maintains his commitment to reality. It would be true to say that Sembene portrays Diouna as a victim, but he had ample reason; he once said: “The development of Africa will not happen without the effective participation of women.” Jusu, on the other hand, has created a protagonist who from the start is far more headstrong, and an Act III workaround appears with a modest ration of Cinderella for the audience.

Both films can be viewed for free: Black Girl on YouTube, and Nanny for those who shop at Amazon, without any rental charge.

dj.henri is a New York City DJ who has performed at the Apollo Theater, B.B. King’s, Symphony Space, and elsewhere. He is also the creator of radioafricaonline.com.

Related Audio Programs