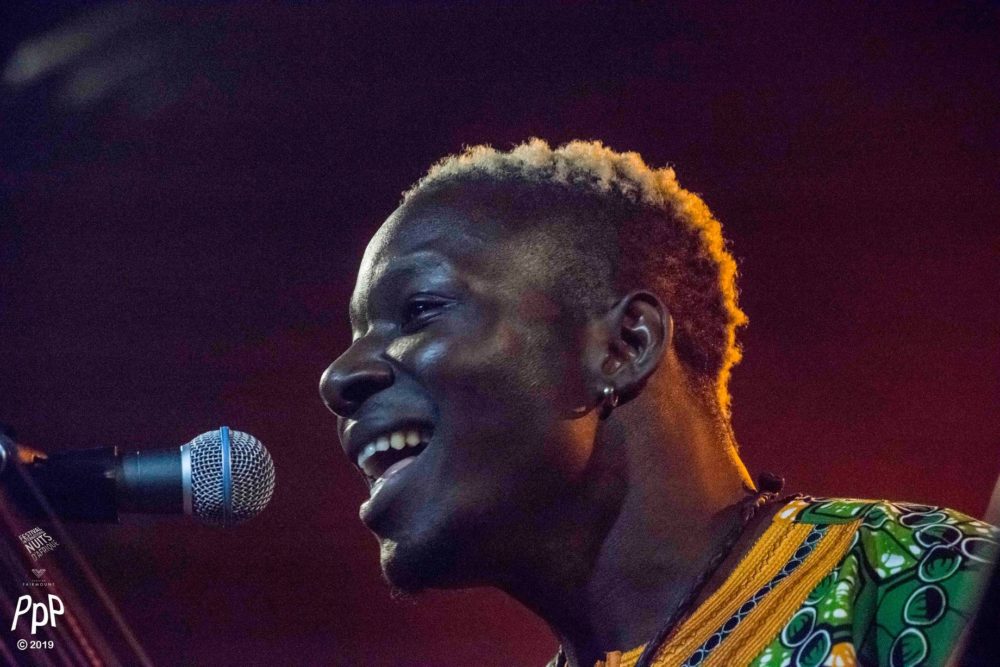

Like all major cities in North America, Montreal is a city that ever renews itself via new immigrants. Whether it's food, culture, science or the arts, what they bring with them gets added to the clay that shapes their new home. A year ago, a talented musician from Mali came to Montreal with an instrument of his own design and very quickly found himself welcome to the family of musicians here, performing wherever and whenever he could, eventually forming his own band. Entering this year's Syli d'Or competition sponsored by the Festival International Nuits d'Afrique, which seeks to recognize and reward emerging local world music talent, this new immigrant faced off against 35 other groups, and not only did he take the top prize, but also the “People's Choice” award and our own Afropop Worldwide award. His name is Mamoutou Dembélé, but he was known in Mali as Baba-MD, and now here in Montreal simply as EMDE (pronounced in the French way, “Em-Day”).

The Syli d'Or prize, as Nuits d’Afrique general manager Suzanne Rousseau explains: “give(s) artists the tools to succeed. They get a video from it, professional pictures and a CD. It gives them a website and gives them the tools to promote themselves internationally.”

We sat down with EMDE before he gave a drumming workshop at the Festival International Nuits d'Afrique, and spoke through a translator about his journey to Montreal.

Ron Deutsch: You grew up in Sikasso, Mali. Was “Baba-MD” a nickname you had as a child?

EMDE: “Baba” means father. I have my grandfather's name, so I can't just say “MD,” and so I have to put 'Baba' before it as a sign of respect. He was a great man, so I put that title before it. He was a griot and a great unifying presence, bringing families and villages together. I am a griot as well, and carry this tradition through music and dancing.

Did you start playing music when you were very young?

Yes. We are a family of warriors and griots and so are genetically wired to be musicians. In the same way a family of a king will pass on his title, we pass on music and dancing to our sons and daughters. It's like our family heirloom. It's genetic. I have four brothers and one sister from my mother, but between my uncles and aunts I have many cousins who we consider to be like brothers and sisters too. Almost all of them are griots and artists, but in today's modern times it's become harder and harder to make such a living. Originally, the griots would make their own instruments and preside over marriages by singing, playing at ceremonies and would guide whoever was the king, or whoever was in power, towards the right path of wisdom and morality through music and chanting. Much like a religious priest, but not. However, we can't make a living at that any more. So many have to try their hands at other things to survive. They still play for traditional events. I have one brother who is also playing music professionally.

Because of the tradition, our parents give us instruments to play with when we are just seven months old. Partly, because many children then didn't survive past six months. So if a child lives to be seven months, they give us little instruments and just let us tap on it and get the feel of it. And as we grow up, we are given bigger and bigger instruments. And as soon as we are able to walk and hold something, we are trained to be musicians. I went to regular school for a while, but I didn't excel at it. But already at six years old, I excelled at playing the drum.

You not only made your own instrument, but it's a new kind of instrument, yes? Yes. The classic griot instruments are the result of centuries of wood-making and craftsmanship. But I felt when I was playing these instruments that something was missing, some tones, they didn't sound exactly the way I was hearing in my head. So I decided to make my own instrument, which I call the bahouinou. The one I play is the still the first one I made all by myself and finished around 2001 or 2002.

EMDE’s bahouinou is a 15-string instrument--somewhere between the kora, which has 21 strings and dates back to the 14th century, and the kamele ngoni, which can have between four and 16 strings, and was invented in the 1960s. They are both made of leather and a gourd, and both considered part of the harp family of instruments.

My bahouinou is hand crafted and took a long time to make. I had to cut the pieces of wood I wanted. They had to be treated for two weeks in a kind of butter which I cover the wood with and then let dry outdoors. The oil soaks in and protects it from the elements.

How did you parents feel about you leaving Sikasso and moving to the big city of Bamako?

Originally my parents weren't really against me performing in concerts, but my father didn't want me to stray too far from our home. It is very important where I'm from that kids don't roam too far away because something awful may happen to them. Because technology wasn't what it is today, they worried what may happen to a griot's child. They could be kidnapped, be exploited, or, yes, sacrificed to the altar of the gods. People were worried what would happen to talented griots if they strayed too far from home, and that's why my father was originally afraid. Eventually, he accepted this path for me.

When I first moved to Bamako, I played a bit with my brother in his traditional band, doing weddings, ceremonies and stuff like that. But I didn't like it much because it was too restraining for me. My brother always wanted to just keep me on the drums.

A year later, in 2005, when I was 21, I started my band Maa-In. It was originally a percussion band and we became very big, playing at the French Embassy in Mali and a festival in Nigeria. People were very impressed that such young people could play so well.

With Maa-In, we were able to make some money, and I was always going around to bar owners, especially where expatriates and foreigners hung out, to ask if we could play. I never had a manager. I always did the managing by myself. So I basically just developed my own network to get gigs. Even if the money wasn't so good, I would only keep just a little for myself and give rest of the money to my band so they could survive. My father was a farmer who did well with his crops, so I didn't have to send money home and could pay my musicians decently. And because I could pay them decently, they wanted to keep playing with me. I don't care much about money and only needed just the basics to survive, I just really want to have good musicians to play with and treat them right.

Also, with the money I would get from playing my brother's gigs, I would buy concert tickets and observe how other musicians worked, how they communicated on stage with audiences, how they played together and how they passed on their values and passion to the public. After the shows, I'd go talk to whoever was in charge of logistical operations to see how you get into a venue and meet people from the festivals. Also I was meeting more well-known musicians and was able to become friends with some of them. I would offer them tea, even wash their shoes or cars, as a sign of respect, just so I could get closer to their knowledge of music and the music business. People like Petit Adama Diarra.

Eventually, you went into the studio and produced an album of your music: That was in 2014?

Not exactly. So what happened is between 2008 and 2010, from all the gigs we were playing, I would put money on the side to record an album. I wound up saving enough and gave it to the studio. Then I saved up money again and this time I gave it to [Salif Keita's kamale ngoni player] Harouna Samake to be a part of the album. And then I did it once more to be able to pay all the rest of the musicians, you know, for food, travel and even instruments. Once all of them were paid I was able to record the album in 2010. I had to have Samake on the album because I'm crazy about his style. He's a grand master of the ngoni. We have a big brother/little brother relationship and we go over to each other's house and drink tea and talk about technique. He got me a better price for the studio too and helped polish the album. So we recorded some of the tracks at Salif Keita's studio Le Mouffou in Bamako, and the rest we did at Samake's own studio, Sama Studio Records, also in Bamako. I also got Mariam Koné to sing a duet with me. She is a great singer with both great patience and passion for her art. We have also worked on other projects together.

Mariam Koné is an award-winning singer from Mali. In addition to her solo work, and as a backup singer for Cheick Tidiane Seck, she is a member of Les Amazones d'Afrique, a supergroup of West African female singers who seek to promote women's rights, including Angélique Kidjo, Mariam Doumbia (of Amadou and Mariam), Oumou Sangaré and Nneka. They released the album République Amazone on Real World Records in 2017, and the song from the album, “La Dame et Ses Valises,” was chosen by then U.S. President Barack Obama as one of his top 20 picks of that year.

So we finished the album, Djeliya, and brought it to my brother, the one I played with, and he said the album was no good. He said I had no good singing voice. But he never actually listened to it. Later, when it officially came out, the wife of Petit Adama played it for my brother, and he was shocked, telling her in no way that could possibly be me. These are the tracks on Soundcloud.

The album didn't come out until 2014, because I had to raise even more money to package and distribute it. But I was now getting more well known in Mali, Senegal and Burkina Faso, all over that region. Both for my band, but also because I was working with Souleymane Koly, playing and dancing with his troupe. This was also a very rewarding experience for me.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: Koly, who passed away in 2014, was a dancer, playwright and choreographer who founded the Ensemble Koteba of Abidjan in 1974. Koteba was originally a form of theater that takes place during harvest times in villages, using satire to retell the deeds and misdeeds of the villagers. Koly updated this tradition for the stage, combining music, dance and theater. Many musicians, including, Ali Farka Toure, Manu Dibango, Ray Lema and Manu Dibango worked with Koly over the years.

In 2014, EMDE was one of the musicians who participated in the Africa Express recording of Terry Riley's minimalist conceptual composition “In C,” along with 16 other musicians, including Damon Albarn, Brian Eno, Cheick Diallo, Badou Mbaye and Alou Coulibaly. In 2015, EMDE contributed to the compilation album, Lost in Mali, from Riverboat Records, which included his recording, "Taro Maro" (AKA "Taworo Maworo") which critics pointed to as one of the standout cuts from the release. He also released his own second album in 2017 and toured as a member of another dance troupe led by Fatou Traore.]

So how did you wind up in Montreal?

It was my destiny to come to Montreal. But in the beginning, my interest in Montreal began around 2004 and 2005. I had a friend who lived in Quebec and would send me pictures and videos. I thought it looked so interesting, but I never thought I would have the chance to actually get here. Then in 2011, I was asked to record with the [Haitian-Montreal] musician Vox Sambou.

Sambou had been invited by the Canadian consulates to conduct music and arts workshops with young homeless and at-risk kids in Mali, Senegal and Burkino Faso. According to Sambou, EMDE was referred to him by the consulate in Mali as someone to collaborate with. We asked Sambou to tell us the story about what happened.

Vox Sambou: I wanted to record a couple of songs for my album Dyasporafriken while in Africa. We were supposed to record at the studio of Tiken Jah Fakoly, but the studio was having problems and they couldn't get it working in time for us. So finally the time came and we had to go to the airport to leave, but on the way there the airline called and said the flight would be delayed for some hours. And so EMDE then took us to Studio Bogolan [founded by the late Ali Farka Touré] and we were able to record tracks for two songs – “Maliayti” and “Dyasporafriken” with EMDE and my other band members of the time who were on the trip with me.

Here's also a 10-minute video that documented Sambou's Malian adventure....

EMDE: So then I was originally supposed to come to Montreal to go on tour with Vox in 2012, but I couldn't because of all the other things going on with my album and other projects. But I perform with him often now, and just returned from performing in his band at a festival in Abidjan last week.

But about Montreal,I was introduced to this woman who was from there, and she eventually came to Mali and we got married in 2015. I wanted her to stay in Mali, but she wanted us to live in Montreal because of her family and friends. And so even though I had all these projects and tours planned for the next few years, I gave this all up to come be with my wife in Montreal in 2018. So, you see, it was my destiny to live here.

Here is a clip of EMDE playing with Vox Sambou's band, which he does regularly in Montreal, at this year's Festival International de Jazz, along with Bokanté's lead singer, Malika Tirolien.

Were you surprised by winning three prizes at the Syli d'Or this year, and what do we have to look forward to in the future for you musically?

I was so surprised that people here have responded so well to my music. I didn't think it would have been so accepted as it has. It was also great to see Salif Keita. He was another who helped me with advice over the years and I have a great respect for.

Now I've been here for a year, I have lots of things in the works. For example, when I was younger, I didn't think much of education, but now that I'm older I realize how important such things are to prevent one from being exploited and how important is to be able to read and write well in French. So I want to create my own charity that will help musically talented orphans and underprivileged kids in Mali become the next generation to carry forward the tradition. I'm also going back to school here to learn audio-visual studies.

Since I've been here, I think my music has changed some because of all the new experiences I've been having. I also want to bring my band from Mali, Maa-In, here so I can unify them with my band here and really have this great group, but also for them to experience new things too. I am also thankful for the musicians here in Montreal that I'm working with who believed in me to go on this journey with me.

Well, we look forward to hearing and seeing all your new projects. Thank you for your time.

Thank you so much for awarding me the prize and for your time.

Related Articles