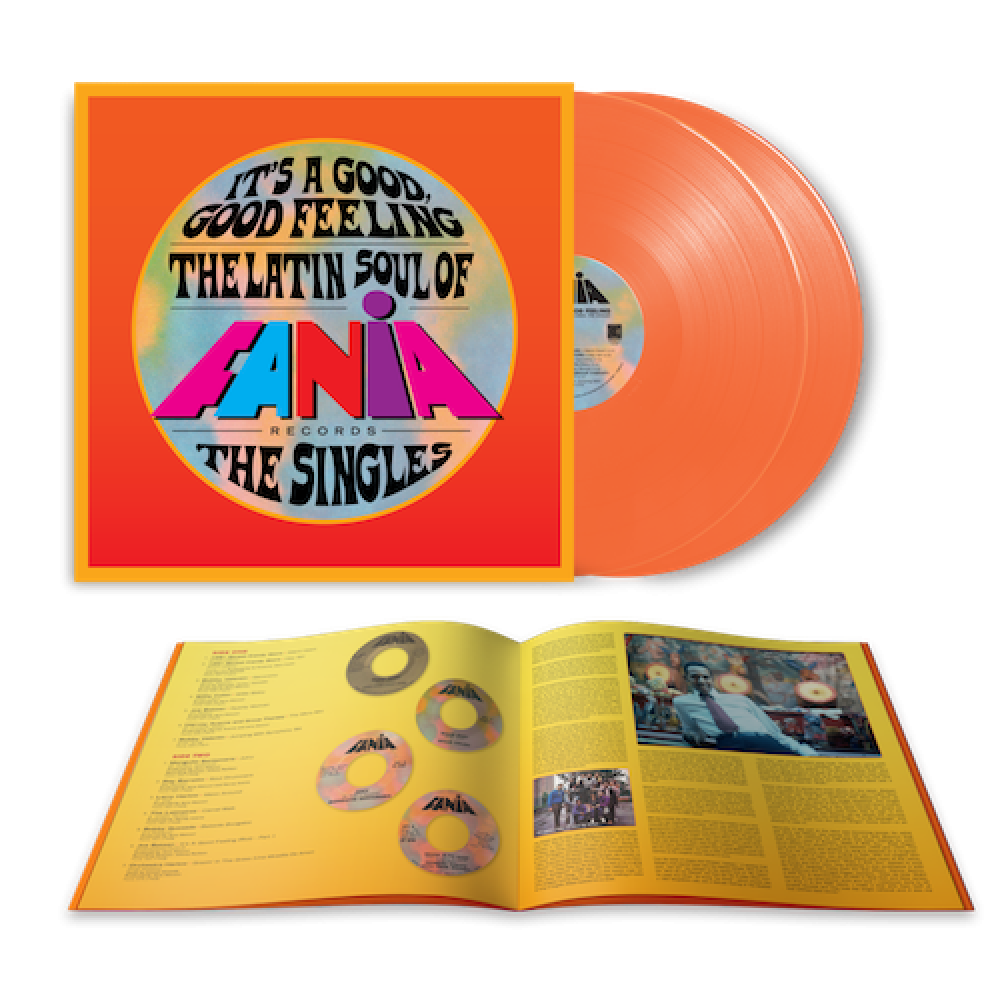

Fania Records is coming back to the vinyl stacks. The pioneering salsa label’s back catalog is now being managed by Craft Recordings’ Craft Latino imprint, and they’ve already re-released albums from Willie Colón, Ray Barretto and Celia Cruz among others, all classics, mostly already sold out. Just this week Craft announced a special collection of Fania singles coming out in your choice of a double orange LP set or an expansive box set.

Craft Latino reached out to tell us about the Oct. 22 release of Ismael "Maelo" Rivera's Lo Último En La Avenida and Angel Canales’s Sabor coming out Aug. 27, which piqued our interest—first off, how do we get the records to review them, but also, how did Fania end up with Craft Latino? So, we asked.

Bruce McIntosh is the VP of Craft Recordings Latin catalog, but he took an interesting path to get there. On a phone call with Afropop’s Ben Richmond, McIntosh laid out where the treasure trove of Fania Records’s vaults has been, and relayed his personal history as a music industry lifer. He’s gone from being a buyer for the late New York institution Nobody Beats the Wiz through the dawn and then demise of the CD era and into the 21st century world of back-catalog stewardship.

Mortifyingly, the recording device used to capture the conversation missed the very end, but the gist is that there’s even more exciting Fania re-releases on the horizon, following the box set in October and a release slate for 2022 that comes to two albums a month—as fast as the record plants can get them out.

Afropop's Ben Richmond: So Craft Latino is reissuing from the Fania vaults—I saw that there was another announcement about that this week. You used to be a general manager of Fania Records, is that right?

Bruce McIntosh: Well, not the original Fania Records. Most of those guys are not around anymore because the label started in the mid-to-late ‘60s. I came into the picture with the previous owners, which was Codigo Music and the owner before that which was Emusica. Emusica was the one that bought it from the family of Jerry Masucci.

Fania started up in '64 and wound down and late '80s, when Masucci simply just got out of the business and moved away to Argentina, where he passed away in 1997. The business was owned by the estate and run by a guy that was distributing the product at that time and Emusica bought from the estate. So that was really the first time that the catalog had gone out from, under basically, just local Latin distribution. Emusica bought the catalog and for the first time CDs were reissued at that time in 2006. For the first time, the catalog really made it out into the mass merchants and the Best Buys of the world and everywhere else. And after that Codigo came in, and that's the company I worked with for 10 years and was the general manager there. And they continued reissuing: did some vinyl, merch, basically brought the company into the 21st century—digitally set up social media platforms and profiles and the dot com with merch and so forth. And then Concord just bought Codigo in 2018, and I kind of came with the package there.

Ben: O.K., and Concord is the parent company for Craft?

Yeah, Craft is the catalog division of Concord. Concord is probably the largest indie in the world, so when you're talking about the size of us, it's just immense. There's a number of labels and repertoire under Concord that is just mind blowing, you know, everybody from Creedence Clearwater Revival to REM to Coltrane to Billie Holiday. It's a very big company with a lot of prestigious labels and the catalog division of Concord is Craft Recordings.

It's back catalog, but we do things to keep it current. Of course it's a huge part of the business these days. You hear a lot about the frontline artists and whatever is popping, but you don't always hear that 60 percent of the streams at any time on Spotify are basically catalog. People tend to gravitate back to their favorites, you know, and on top of that, you've got a whole other generation coming up, discovering the classics: the Creedence Clearwater Revival's or the Willie Colons and Celia Cruzes. Catalog is a very, very important, part of the business and it's what keeps the lights on and keeps the wheels turning in this industry.

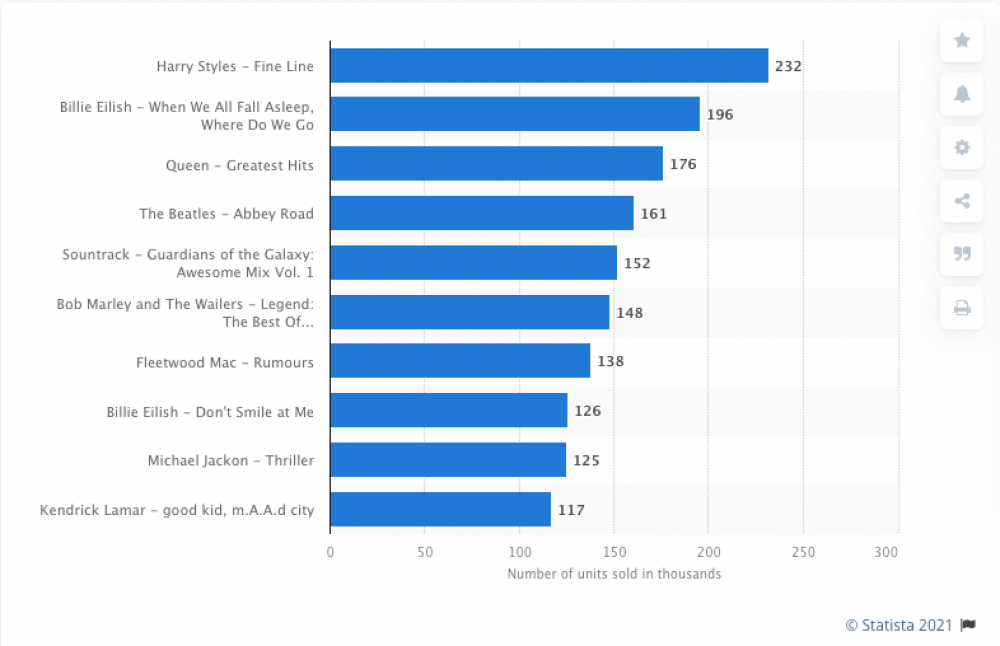

Yeah, I feel like the annual list of most popular vinyl will have a Taylor Swift on top of it, but then three or four down is like Dark Side of the Moon.

Yeah, it never goes away. The Taylor Swift will drop out in a year or whatever, but the Dark Side of the Moon will still be there. So, it's a really exciting part of the business. You have to be creative to keep things going, you know, and not just rest on whatever airplay there is there, if there is on some classic rock or jazz station. You really have to be creative to keep the catalog relevant and keep it out in front of the consumer.

I think Fania has a lot of potential for that. Can you talk about what sort of attracts you to it? It sounds like you kind of came to it through the side door. Are you a fan of the music?

Yeah, I definitely came through the side door. I was just out of high school going to community college taking Spanish class. It was funny, I was working in a shoe store and I was lucky enough to have a good friend working with me from Philadelphia. I grew up in Central Florida in a small town and I would not have had much exposure to this music--it wasn't on the radio there, you had to really seek it out. But I had a friend that was really heavily into jazz and I got into jazz and then from there I moved on and started working at a record store. There, I discovered Latin jazz, you know, artists like Tito Puente, some of these artists that were on a label called Concord Picante at the time, Eddie Palmieri and Tito Puente and Poncho Sanchez—these are all Concord Picante artists.

I was listening to that, you know, so it was a natural graduation into Latin jazz. And then from there, salsa was the next progression. And I was studying language at community college and had my little pocket dictionary, so I'm like, "what are they saying?” You know, I love the drumming and the percussion, the piano riff. It's all incredible music, all Afro-Cuban based music. I was just wondering, "what are these lyrics?" What are these choruses, what do they mean?” I had to learn the language to figure out what was being said, and fully understand the music, but actually looking back, I actually learned a lot of Spanish listening to Fania.

I moved to New York and I was a buyer for Nobody Beats the Wiz and they didn't have Latin music at the time, which was just mind-boggling to me. So in late '80s in New York and Brooklyn, Bronx and Queens these stores, these were the stores where, you know, records were being broken and early hip-hop and r&b and, you know, it's a very heavy Latino population but they had no Latin music. So, I asked my boss at the time, "why don't we have Latin music?" He said "Well, somebody was racking us before, the distributor was giving us all the returns that they have from the other accounts." I said "Well, let me do it. Let me get a section in this store and in the Brooklyn, Bronx and Queens." So we set up these little sections in the stores and the product just blew out. We would ship product on Tuesday and by Friday, the managers were calling, screaming, "Hey, I need five more of this, 10 more of this," and it was just a big success. That's when I said “there's a business here.”

And then I worked for a couple of different companies—strictly Latin—worked with Handelman Company who racked Kmart and Walmart stores at the time. And then I actually left the country. Moved to Brazil. Working with Handelman. We set up the Handelman company in Mexico, Argentina and Brazil. So I've got some international experience there. And then I came back to the States in 2000 and worked for Universal Music Latino, which was the Latin label. And they owned a couple of other salsa labels as well. So that's where I got to work with the catalog. Then from there, I jumped over to Fania at an opportune time with Cotigo and that's kind of my story. I was not there in the ’70s, in the heyday of salsa. That was before my time and I was, you know, basically a generation too late for that, but I got my education in it.

It's very cool. Do you remember Fania from when you were like stocking and buying? Did they have distribution in your guys's shops?

Oh yeah, at The Wiz we would buy from the local distributors as well as the majors and larger distributors. And at that time there was, you know, there were LPs and CDs at that time in the ’80s. So it was a big network of independent distributors whereas now you basically have maybe two or three in the U.S. At that point, in every major city there was a distributor, and they all carried different lines. Certain labels would be carried by certain distributors and you know, so there was a big network of people to go to. So I would get all the Latin stuff from very particular distributors. And we put it in the stores and it just blew up and turned into a real big business. It was a small business for everyone at one point, even the majors. At some point, I'd say in the ’90s, with the chains that are no longer around—the FYEs of the world, Camelot Music and Record Bar and Sam Goody’s, those guys—they all got into Latin very heavily in the ’90s and it just exploded. Everything went gangbusters up until, you know, the time when CDs were kind of fading when Napster came in around around 2000 or late ’90s.There was a big change and then soon Apple came with iTunes and that really changed everything.

Yeah, this entire physical-object distribution network is just not there anymore.

Yeah. All gone, all gone. But it's very interesting because Latin really suffered because there was a lot of piracy on the CD side in the U.S., but Latin America never really went into the download phase because nobody could really afford it. You know, you have to have a credit card and had to buy on iTunes and in Latin America, some of these countries, most of the countries, maybe only 20 percent of the population could even afford it and even then a lot of people didn't have credit cards. So the download phase just did not happen in Latin America.

And what's happened with streaming is I guess you could call it a democratization of music. Everyone has a phone no matter what socio-economic level you’re from. Everyone has a phone basically. It may be pay-as-you-go, they don't all have plans but they have access to streaming that way with Spotify “freemium” or YouTube—they have access to music. So now whereas before the market was taken over by piracy because the socioeconomics were just not in place for the entire population. Now you've got everyone participating, which is interesting. So, you know you've heard about Latin with billions and billions of streams. And the top streaming artists of Spotify, a lot of them are Latinos doing reggaeton or different artists. And it's all because Latin America has been democratized. There's been a lot of reports about Mexico City being the number one city for streaming in the world. It's because it's a population of 20 million people and everyone's got a cell phone now, so music is basically accessible for free on some platform or another. So that's been really interesting.

Fania is unique in itself. It's much more than the music and the musical movement that took place. It coincided with the whole social cultural movement in the U.S.—of the Latinos in coming in and immigration and to the U.S., into New York and Chicago. The Puerto Ricans that came early on in the 1900s and then the big immigration in the ’50s when they came to New York.

That's kind of what Fania was bred out of. They have kids and then these kids that were coming up in the late ’60s, from the parents that moved and the ’50s. The kids that were coming up in the late ’60s, they're the ones that wanted to step away from their parents' music, which was the mambo, and the cha cha cha and the traditional Cuban rhythms. They wanted something to call their own. and you know, they basically got their footing and stake claim to the neighborhood with Latin soul, boogaloo and then the salsa movement came out of that in the early ’70s and probably went from the early ’70s to the mid- to-late ’80s. It was just a huge force that came on very much like hip-hop—or hip-hop came on very much like Latin music did prior.

It transformed everything because they went from their parents’ music to the new genres and you know Fania was right there to ride that whole movement and that's why today it's more than just an iconic label that has this repertoire. It's a symbol of Latino power and it's something that represents a motion to these people. If you wear a Fania shirt—I don't know if you checked out our website—but the Fania logo tee is kind of an iconic logo and people see that and you wear that shirt anywhere where there's Latinos or in a big city, you'll get stopped on the street and people will point at it, give you a thumbs up. It brings out emotion. It's very, very unique and that sense. Of course you have other labels that are like that: Blue Note and Def Jam, Island, which is known for reggae, but Fania goes beyond that because of the connection with the people. It was Latinos not just from Puerto Rico, it was Cubans, Dominicans, Ecuadorians. It was all something that they could have in common in New York, basically.

The other thing that's funny about Fania is everything was done in New York. It wasn't done in Latin America, you had artists from all over the place, mostly Puerto Ricans and Cubans, but it is all produced in New York City. So it's American music. It's really American heritage and that's unique for a music in another language to have its home base in New York City.

There's something like boogaloo before it and on many Fania Records releases that are just so specific—you can tell that they're made uptown. There's that part in Joe Cuba's "Bang Bang" about "cornbread and chitlins" and they're singing over a clave about soul food. Like, “O.K., so you must've lived in Harlem."

That's right out of Harlem. Straight out of Harlem. And these guys, most of them started in Spanish Harlem, you know, Tito Puente and these guys. The Bronx was probably the next area and then some of the guys were from Brooklyn as well and the Lower East Side. But it was a very Uptown thing. It was stickball. They were mixing with local food and culture, and people from Harlem would go to East 116th Street and to a Latin restaurant and eat rice and beans, you know, so it was very much a melting pot there.

And I think also Larry Harlow being on the first vanguard of Fania out there, yet he’s a Jewish guy, is very New York.

Yeah, that's a whole other thing there. There was a big, big cultural thing with Jewish people. Before the Fania era, when it was the Mambo and the cha cha cha, they were going to the Palladium to these dances, and it was a lot of white people. It wasn't just Latinos there. Everybody was learning to dance these dances and they loved the music. But that was a generation before Fania in the ’50s and it was big bands—Mambo Kings, Tito Puente, Tito Rodriguez. These guys were like the three top dogs and they were battling each other. It was very competitive and the people that were dancing to their music, there were Latinos, there were Jewish people, there were all walks of people because the dance was the big draw to it.

Then like I said earlier, the next generation that the sons and daughters of the people that were out at these dances are the ones that didn't want to listen to their parents’ music. It wasn't wasn't cool anymore and they wanted their own music. They were into r&b and doo-wop and things like that. They wanted their own music and they created it. They made it. And that's what you know, what we call salsa today was bred out of— there's always the Afro-Cuban sounds in the roots and the origins and then even going back to Africa. There's the drum patterns and things that you'll notice in this music, but they made it their own and gave it their own style at Fania.

Yeah, it's interesting like so much of the music that attracted me to Afropop is all this Afro-Cuban music that ends up back in Africa. These African bands that were doing like, very mambo or rumba and Cuban influenced musical forms, and I didn't really stop to think about how Fania and salsa, is a sort of American version of that.

There was some sort of connection also with Pacheco and Africa. He's written some songs about Africa and I'm not sure, but somehow they knew him and when they went in '74 to Zaire to do the show, the Fania All-Stars went. There were also other bands—James Brown was the headliner and they had a whole music fest to go along with the boxing match [Foreman-Ali in Zaire, 1974]. The musicians were all on the plane together and when they landed James Brown was like, "I'm going out first—They all want to see me," and they had all these people around the tarmac and fence and he walked out and there was applause but it was not like what Johnny Pacheco received. Johnny Pacheco later walked out in the whole place went crazy. Somehow they had a connection to Pacheco and they have been listening to his music and it was just amazing. He was a star there. And of course, the Fania All-Stars were instant stars there because of him. So yeah, Soul Power is the name of the film that documents that, and we also have our film Fania All-Stars Live in Africa that you should check out.

Yeah. They released some of the African artists who performed it that it is just called Zaire ’74. You can hear Franco and T.P.O.K. Jazz doing their kind of Congolese/Afro-Cuban influenced music.

Manu Dibango also played with Fania Stars. He was at the Yankee Stadium show and he's on that record and in the recording studio. I don't know if you have this story of that show but it was the first time a Latino band played Yankee Stadium. They had to pay a huge safety deposit for the field because they were worried about the field getting torn up. And sure enough, people jumped out of the stands and were running towards the stage on the field. Completely tore up everything and the show got stopped because people were starting to climb on stage. And so there's not a complete recording of that show. It was later redone in the studio and also some recordings from Puerto Rico were used to complete The Fania All-Stars live in Yankee Stadium. There's actually two volumes of that. But yeah, going back to the African artists, Manu Dibango is on that and he does a version of “Soul Makossa,” which is just fire. It is just incredible, you know.

At this point, of course, the recorder shut off. The gist of the rest of the conversation is that you should keep an eye on Craft Recording's site for more Fania Records reissues!

Related Audio Programs