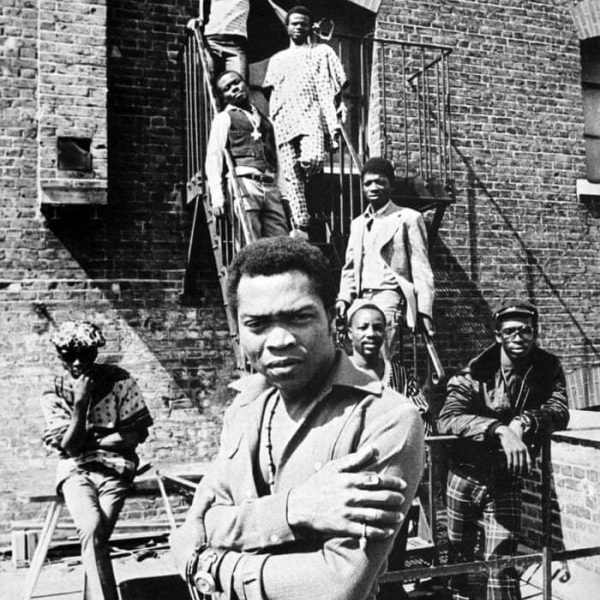

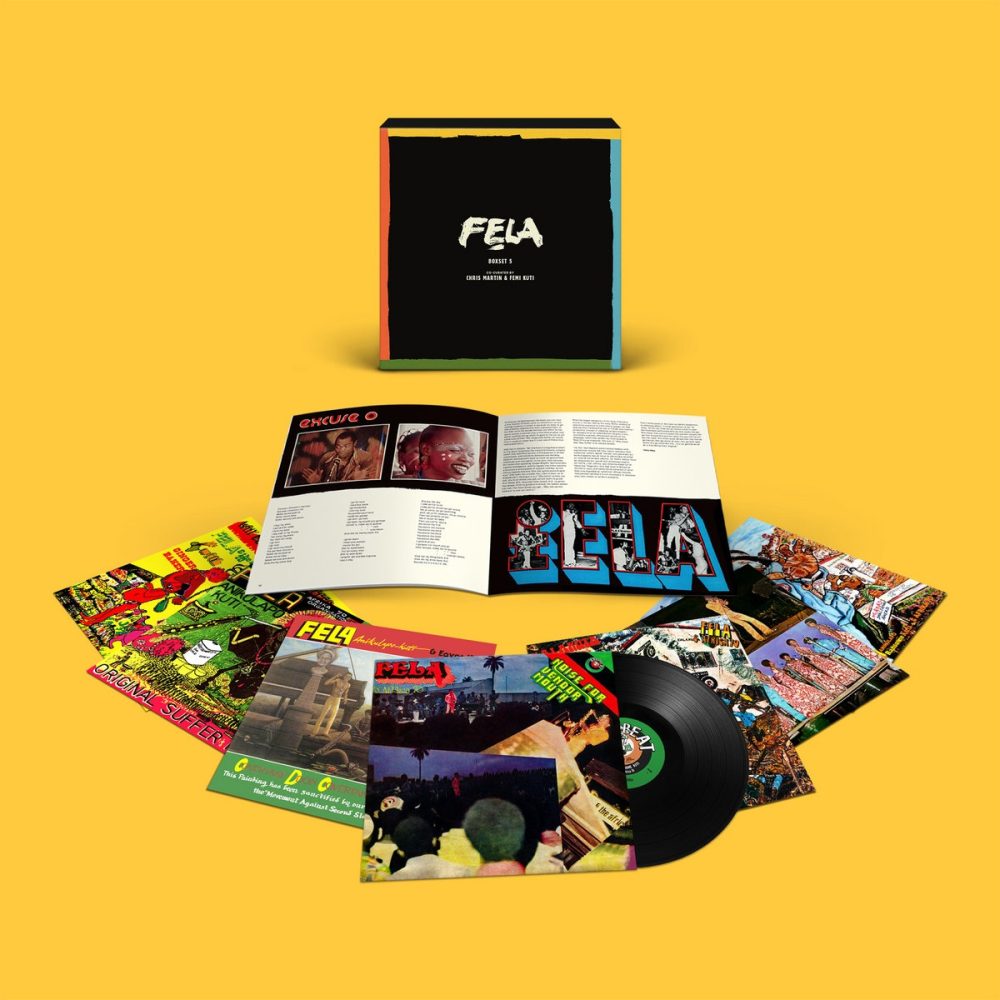

After Erykah Badu, Brian Eno, Questlove and Ginger Baker have all had their turns selecting box set contents from the Fela catalogue, it’s understandable that many of the most memorable songs and jams are already in the pot. (Ginger Baker tapped my personal favorite, “Roforofo Fight.”) But Chris Martin and Femi Kuti have nevertheless come up with a rich set from what remains, especially for its focus on the peak creative years of Africa 70, the band with which Fela first articulated his penetrating critique of Nigeria’s official corruption and systematic oppression of the poor, and the band that featured the inimitable Tony Allen on drums.

These box sets are treasures to behold, in this case seven LPs with the original artwork and a LP-sized book with lyrics and informative notes by veteran African music writer Chris May. Listening to Fela on vinyl is a unique experience, as each side contains just a single song, running up to 20 minutes—the exception being the final LP in this set, “Overtake Don Overtake Overtake,” which divides one song between the two sides. Experiencing Fela this way obliges you to consider each piece not only as a stand-alone composition and a singular statement, but as a physical object. Somehow that focuses the mind.

The earliest track, “Why Black Man Dey Suffer,” was recorded in 1971 but not released until 1986 due to its forthright statement of Fela’s fundamental manifesto for the first time publicly. Words that seemed daring and dangerous in 1971 would soon become commonplace for Fela, the reality of that danger notwithstanding. This song and its B-side “Ikoyi Mentality versus Mushin Mentality”—which pits the Ikoyi elite against the stepped-upon common folk of Mushin—were recorded with drummer Ginger Baker. This was no casual jolly by the British rock icon. Fela had known Baker from music school jams in London in the ‘60s in London. There was an established musical friendship well in place by the time Baker hit Lagos after a long overland journey across West Africa in 1971. He stayed until 1975, building a studio, even filling in for Tony Allen when the maestro was ill. The connection was deep.

That said, Baker lays so deep in the grooves that you wouldn’t know he was there if you weren’t told. Two things strike me as I listen back to these early Africa 70/Afrika 70 tracks. First is how clean and spare the sound is. Drums or percussion often start first, strong and simple, and as each new element is introduced, its presence is sharply defined building the momentum steadily. The brass section provides the rocket fuel. Solos vary from brilliant—notably from Lekan Animashaun on baritone sax and Tunde Williams on trumpet—to quasi-possessed: Fela can be quite good on alto sax, but can also sound clunky and flailing when soloing on keyboards. I remember having that impression on the two occasions when I saw Egypt 80 perform live in the 1980s, and listening back today has not revised it.

The second thing is how briefly Fela sings on these tracks. After a lengthy instrumental buildup, he states his case with fierce economy before the band settles back into a lengthy outro jam. That pattern continues on tracks from 1975, a peak productive period for this band. “Noise for Vendor Mouth” brings in Afrobeat’s signature tangling guitars—one playing a low ostinato, the other high chippy-chop chords—as well as the growing female backing chorus. Once again, Fela delivers his message without embellishment. “Dem say we be hooligan / We no talk we no answer” about sums it up. So few words and so many notes, almost the inverse of yet-to-be-invented hip-hop.

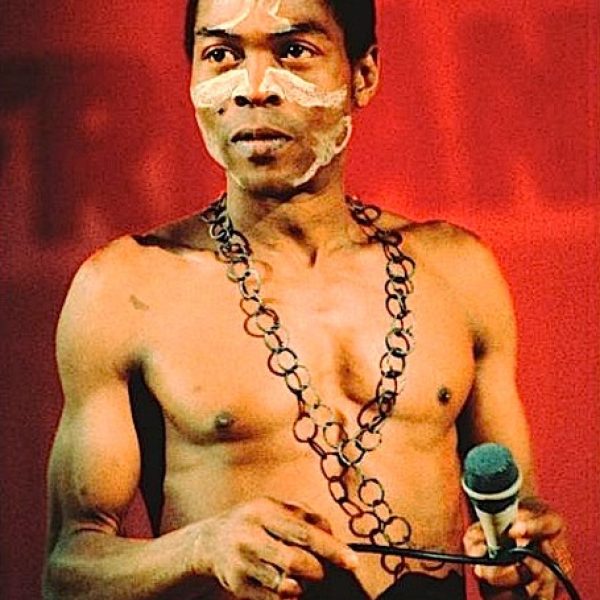

The flip side, “Mattress,” is an interesting one. Somehow the song that got Fela in gender-bashing trouble—and rightly so—has the punchiest feel and strongest melodies of the set to this point. The lyrics are almost comically offensive: “When ah say woman mattress, ah no lie.” But the music explodes with creativity and energy. On keys, Fela is at his best when he purrs and moans with sustained Fender Rhodes chords while the guitars and brass duck and dodge with the rhythm section.

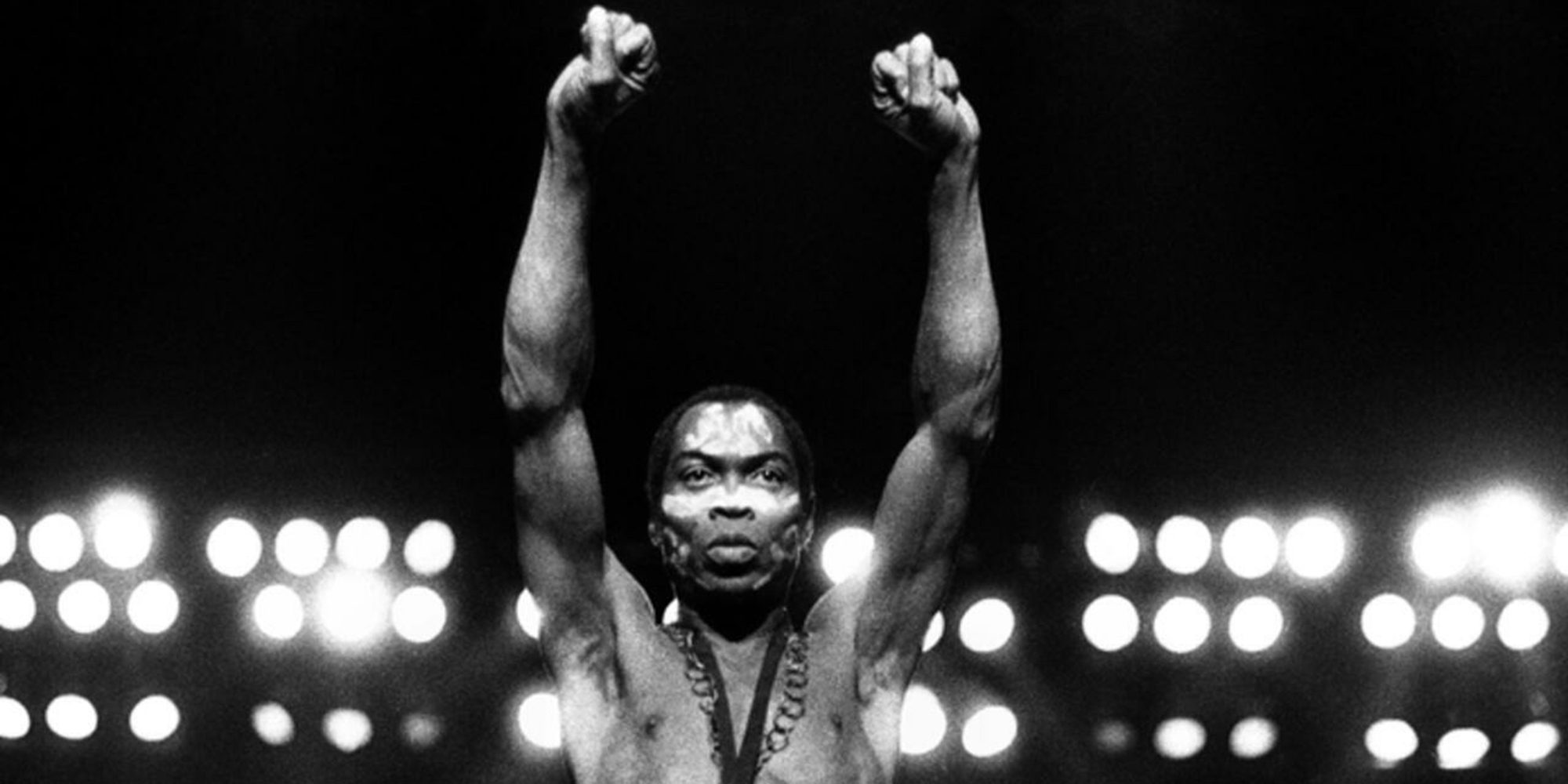

On “Kalakuta Show,” coming at the end of 1975 after the violent army raid on the Kalakuta compound, we get a lot more words, and new passion in Fela’s voice, which breaks at times. Now Fela has a story to tell, and many more to come as he moves from being a social critic to the narrator of his own embattled saga.

“Excuse O,” also from 1975, brings us the first truly fast song in this set. Keys and guitars are electrifying and the brass is as tight and funky as any on the planet at the time. In a departure from the soapbox, Fela tells a playful tale about a near-fight in a bar, over money and a woman, of course. Chris May notes that these are hardly Fela’s most memorable lyrics. Maybe so, but this is one hell of a jam!

On the flip side, “Mr. Grammaraticalogylisathionalism Is the Boss” we return to the cool, serious Fela, excoriating the pathos of countrymen struggling to speak “proper” English in order to advance, and reinforcing a sense of their own inferiority in the process. Fela had mostly sung in Yoruba up until 1970. He switched to pidgin hoping to reach a wider audience, but with nary a whiff of falling into the “proper” English game. This issue of language remains a key theme in many Fela songs. Once again, the brass melodies here are exceptional; for me, brass arrangements are the crowning feature of Fela’s musical achievements.

“Ikoyi Blindness” and “Gba Mi Leti Ki N’Dolowo” come in 1976, the year before the famous devastating raid on the Kalakuta Republic. Everyone is in top form here: the band’s force and nuance, its turn-on-a-dime dynamic shifts, and furious crescendos are breathtaking, and Fela’s spitfire vocal delivery shows the pronounced evolution of his oratorical skills.

The collection picks up four years later with 1981’s “Original Sufferhead,” the debut of Egypt 80. This version restores four lost minutes of Fela soloing on organ (not Rhodes), a sharper, more interesting sound, presenting the entire song for the first time ever. After a lengthy slamming instrumental section—forceful if less subtle than Afrika 70 efforts—Fela launches into a stinging, bitter litany of complaint about international exploitation of Africa by foreigners, all landing on the backs of the “sufferheads”—working class Nigerians.

Fela’s increasingly international focus continues on the flip side, “Power Show,” which recounts a chilling story of a border crossing in which Fela stands up to “stone-faced bloodshot-eyed” border guards, and amazingly, lives to sing about it. The song has an unusual groove, more like a four-on-the-floor soul romp than the band’s signature ethereal funk. Late in the track, Fela pounces on his keyboard, now a phase-shifted organ. He wraps up with a woozy, “Phantom of the Opera” organ finale.

This collection ends with 1989’s “Overtake Don Overtake Overtake,” the maestro’s penultimate song prior to his death in 1997. This is the Fela and band I actually saw and wrote about for the Boston Phoenix at the time. Oddly, despite the song’s wonderfully quirky Zappa-esque brass melodies, clever reprises of past hits—"Mr. Follow Follow,” “Zombie,” “Kalakuta Show,” “Shuffering and Shmiling” and “Unknown Soldier”—and Fela’s visceral passion concerning the murder of his beloved mother Funmilayo, the recording itself sounds oddly murky and constructed, far from the crisp, spontaneous efficiency of those early tracks. We feel here that Fela’s saga of confrontation and embattlement has taken a heavy toll.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles