Gotopo is an Afro-Venezuelan artist living in Berlin. She was born in Caracas and began her formal musical training in Barquisimeto, home of a renowned musical conservatory. She trained with a youth orchestra using the El Sistema methodology, but that was just the start. As she releases her debut EP Sacúdete on May 19, she joins the ranks of the Afrofuturist movement, but with a twist. Her ancestry is both African and indigenous Venezuelan, and all of that is central to her genre-bending music and videos. Her 2020 song and video “Malembe” gets to the heart of the matter. “I have several hundred years of grief in my soul.” A deep message, delivered with a sound full of determination, purpose, and even a sense of humor. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Gotopo by Zoom to talk about her career and music. Here’s their conversation.

Banner photo by Juan Jimenez and Diego Gardo

Banning Eyre: Gotopo, it’s very nice to meet you. So I gather you're in Berlin.

Gotopo: I am in Berlin. You just connected with me through time and space.

Well, that's what we do these days. I have enjoyed the songs I've heard, and the video of “Malembe” is fantastic. To start, introduce yourself. Tell us a bit about your story and how you ended up making Afrofuturistic music in Berlin.

Yes. I love to share that because I think for many of us artists, it's a mix between a very physical intangible, but also metaphysical path. The things that move us are usually a balance between those two dimensions, if I dare say, where we coexist in a way. There’s the desire to reimagine a past within a present that is still so strongly influenced by the process of colonization. This is still expanding into the future; I wouldn't say it's ended.

The fact of being an artist I believe gives us a rare chance at exercising agency. For me, this understanding of ancestral futurism meant a way to reimagine the things that were already taken away from me that I cannot anymore recover in a literal sense, you know, history of my ancestors, memory, culture, language, so many things.

So it's a mixture of all that, taking that agency and designing a present and a future in our own terms creatively. I dream about this. I share those dreams in my music and my art, and I know that there will be many people out there who are going through this same process. Through art, we find a way, a magical space to deal with all these things and translate them into other areas where we need to apply and recover agency. Ancestral futurism; for me it's a lifestyle; it's a way of creating.

I think the Afro-diasporic community is quite ahead in those terms. One, there’s a whole movement, with Black Lives Matter and then pop culture takes on Black Panther. Suddenly there's a world, there's an understanding, there's an argument. It's finally a real conversation. So in a way, I feel like I'm doing this kind of Black Panther theme, but more from the Latin American indigenous and Afro-Indigenous side. I think these processes have been going on. Throughout all this history, but right now is a moment when it's really bubbling forth in popular culture.

Afrofuturism is huge indeed. There are so many expressions. I've spoken with a number of artists in the past year or so who are thinking this way.

Exactly. At some point a few years ago, I felt this. I really got this conviction. And more and more as time passes, that pop culture has a new and different kind of power. After somebody dreamed of Black Panther, believed in Black Pantherand turned it into a reality, everybody else gets it, gets the bigger picture, the social picture, the political picture, the magical picture, the historical picture. In the beginning, it's definitely a struggle to get people to believe, to dream and understand when something is quite futuristic and visionary. That’s why it was also a little bit scary because you're always like: Are people going to get it?

But that may be a silly thought. Of course they're going to get it, because it's not just mine. It's a social, it's a moment. It's a movie.

Tell me a bit of your personal story, how you became a musician.

It's crazy. I think my first conscious memory of music is singing. Definitely.

So from singing as a three or four year old, to now… Wow. I play several instruments. I've studied composition and orchestra conduction in classical conservatory, western style European music. I also grew up in a world of traditional music from Venezuela and Colombia. I know a lot of it, and it's part of me. I also grew up listening to pop and r&b in English. That's how I learned English. I always say that because I really never took a course. I listened to English pop, and then I traveled. And that's it.

You’ve learned well.

Because I was addicted to pop music. Like I'm saying, I’ve always been very eclectic. But interesting enough, now that you ask that, I'm thinking: Wow, at this point, I have a lot of technical knowledge in music and things. But everything really started from singing. That's fascinating because everybody has a process to create and compose. A lot of the time it's like sitting with a guitar, a certain chord. For me, everything begins from my voice. I feel it in my body and then it can go anywhere else. It almost never happens otherwise. I have a bunch of funny cell phone noises recorded. It's not just melodies, it's any sort of noise. I sing it first and then everything else comes to be.

I know that. I do that with guitar. You record little things and then later, they grow. You say you play multiple instruments?

Oh, my God. You're really bringing the memories back. I was going to say that the first instrument I played officially is the Venezuelan cuatro. But now that we're talking, I am remembering the first one I really, really played—until I remember a new one—was a little birthday-cake-shaped baby keyboard. I was addicted to that.

You were really young then.

Very tiny.

Then the cuatro.

The cuatro in primary. Then, maybe at the end of primary, I took the guitar because I loved pop music and I wanted to be able to play the songs that I love. So I was playing guitar and cuatro, and through the guitar and the cuatro, I became the assistant of my first real music teacher who came to our primary school. It was like, wow, what an amazing musician I became after a month. And we founded a small traditional orchestra of cuatros and maracas and things like that. And I was learning chords and I was writing all the music for the whole orchestra, which was quite early on as well.

Then when I decided that I wanted to pursue music school, encouraged by this teacher, I picked the piano as my instrument. This was my whole process of studies in composition and orchestra. I could never have enough of this new knowledge.

So, yeah, that's pretty much the path. And after composition and orchestra conduction was when I decided to look for a new place, completely out of my comfort zone, in order to find my true voice. Until then I had been gathering musical and technical knowledge. But I also realized all of these things are cultural languages that are not really, really mine. You know what I mean? And that is when I understood the need for something that really was mine, dear to my soul and authentic to me.

So Gotopo came very soon after. I mean, it really happened when I understood: O.K., I have something to say and it's not perpetuating Beethoven and Mozart or anything of the sort.

I read in your biography that your early music training was through El Sistema. Was that in primary school?

Correct.

What do you think was the role of that in your process? Did that help you to be educated in that particular way?

Absolutely, yes. Because on the one hand, the very fact of having access as a kid who would otherwise never had access to things like that, to education, musical education. Just the access is the first milestone. And then, of course, in the context where we grow up, sometimes in villages, in favelas, or in a mix between the two, which was my case, sometimes you're surrounded by a reality that you cannot really escape. So in a way, these safe spaces become a haven where you have some opportunity to see light through another lens.

The social reality is sometimes very heartbreaking. You know what I mean? It could lead you to places where you don't really want to be, but if you never see another alternative, you will not have a true choice. So that’s a big, big deal. And a second thing that a lot of people don't know… Because I know El Sistema has become very well known internationally as a project that gives opportunity to kids, and all that is true. The opportunity is the first thing. But there's a second thing that goes much deeper. Many kids join when they are like four or five, and they pick an instrument. And after four or five years they are very good at that instrument, which means a lot of them when they are nine or 10 years old, they can teach other kids. And they were encouraged to do so.

That, for me, is one of the biggest ways in which El Sistema transcended socially, because you as a kid are taking responsibility, sharing knowledge. Wow, that's a different type of human being, you know what I mean?

Sure. It empowers you as a young person, because you're passing what you know on to someone even younger.

It’s very unique, very special. It's crazy because I guess the Western world in particular, if you were below 15, then everything had to be like inside some kind of education context. But from 15 on, you could be receiving a very symbolic salary, and then if you started any musical study professional, then you got a second type of salary a bit higher because you're studying. And if you graduated from university, then you got paid like a professional. But here, a non-professional teenager was also getting some kind of pay, which means economic independence in the context of highly impoverished families.

These things are not really mentioned when you hear conversations about El Sistema. But that's pretty great. Those things provide the real transcendence. I don't know, time passes and I guess the budgets change and the politics and everything, but it was like that. It used to be like that for many, many years. And I think it has to be still, even if the inflation is terrible in Venezuela and salaries are less and less. That was incredibly life-changing.

Just before we come to the present and Gotopo, talk to me a little bit about traditional music and how you were exposed to that. Was that in your family? Was it in your neighborhood? How did you get that kind of exposure?

More in my neighborhood. And from the neighborhood, it extrapolated into a passion, a legitimate interest of my own that I kept pursuing. There were nearby villages, places that I could myself visit. This is something we still have in many places in the world, village festivals or celebrations. These are like a kind of ancient culture. Everywhere in the world you have these things, and they usually are attached to a certain musical tradition, certain instruments, certain groups. I've always been addicted to this thing. I love it so much. And everywhere I travel, I always want to go and see what is from there. I want to feel the place through many lenses.

So I did that a lot, and I kept doing it. I couldn't have enough because Venezuela, same as all of Latin America, is musically rich and very complex culturally. A lot of people in the country don't know even 10 percent of it. But look at this. This exists. So I couldn't stop myself, and now I know a lot of it.

That’s wonderful. I've had the privilege of traveling a lot in Africa and I also always love to go to those traditional settings to experience local culture. I play guitar, and I play a lot of styles that I've learned in Africa and that come from much older traditions. It's a beautiful connection. Let's come back to your biography. What brought you to Berlin?

A mixture of two things. On the one hand, it was that moment of my life when I realized that I wanted to have a certain kind of freedom to explore myself artistically with the least conditioning possible and the most possibility to develop a career, especially to transmit something that I considered important to transmit. That was my feeling. So then I might want to consider that it might be too late if I don't leave the country. It was a process that happened quickly. Five months before I decided to leave, I was feeling like, “No.” Even though Venezuela has a lot of trouble, I'm doing something right here.” Like I said, I was a big deal. It was something important in my life.

How old were you when this all happened?

Oh, my God. 20-plus. I can't remember right now. The other thing was that, like I told you, I understood, O.K., what I’m doing is very important, but it's not my legacy. It's not my voice. It's just a perpetuation of something that somebody came up with 500 years ago, somebody who is not even my reality, not my culture, so that's when I decided, if I want to find that voice, I need to get completely out of my comfort zone and go to a place that I don’t know. A new language, a new culture.

It was about the discomfort of getting lost so I could find myself again. And that really happens when you go away from home. It's crazy that I knew that because I had done only one trip, and that taught me the lesson of what traveling does to you. So I felt I wanted to do that at a deeper level.

Why Berlin?

Wow. It's interesting because I didn't want to do like a crazy move. “Oh, let's just go some place randomly because of passion or emotion.” I really took some time to dig a little bit, talk to other friends who maybe had traveled more than me and just talk, share different thoughts. Of course, if you think about the cities everybody wants to go to, Paris, London, New York, they're abusively expensive. It's unrealistic for me. I don't know, I've never been a fan of struggling like that, sacrificing a minimum quality of life, especially if your project is not even ready, because you still need to come up with the ideas. You still need the time to create.

So then Berlin seemed to be way more friendly, way more affordable, and most importantly, it has a lot of infrastructure to encourage and support artists, a lot of public financing and institutions that are there to teach you about the business side of music.

There are so many knowledge resources there. Of course, you still need to learn how to navigate. You need to learn the language.

How was that, learning German?

Oh, my God. I knew it was not going to be easy, obviously, right? But it was crazy, difficult and complicated. But the thing is, I really love languages. I love to learn a new language, and I want to be able to say, four years later, I speak a new language. I knew it wouldn’t be easy. And of course, that's one of the fears that gets to you, like, three years minimum to regain your independence, right? Because you need to speak the language to be able to really be part of a society. You know that you will be kind of living on the edges. So that was a little bit frightening. I won't lie. I won't deny that. And that's why busking was my best friend for quite a while.

Busking. Yes. We see you doing that in your bio-video.

Yeah. It was hard to busk in winter though.

I hear you. I did some of that in my youth. So Gotopo is a name you chose, right? It's your stage name.

Yeah, it's interesting because somebody also asked me yesterday about my artistic direction, like very strategic, very sharp questions. And I told that person, “Well, those are very good questions that I already have. They're part of my process. But I don't want to sell myself too early, for things that are still in an ongoing process.” I’m releasing a mini album now, and I'm already thinking of the second one. The questions are there right now.

But Gotopo. Gotopo. It's a name that I chose because it was the only tangible memory of who should have been my ancestors. I have no historical or cultural memory because my family doesn't have it. I found that out externally on my own. And that was so crazy. I mean, just the fact of realizing that my family has pretty much no clue, at least the family members that I know, they don't really have a clue. I found out that this name belonged to the last indigenous chief of the region where my family came from. And I was obviously astonished by that in a celebratory way, in a happy way. But then I also found a lot of tragedy in that discovery, the forgetfulness, the historical erasure, because I know there's a reason why, generationally, we forgot our people. It’s not because we wanted to forget them, but because there's a process.

There was a system that wanted you to forget.

Yeah, exactly. I mean, understanding this thing is very intense. O.K., there are still many things I left in Venezuela, which means I have the homework of going back, researching, digging, finding so many answers. But in that moment, I was far away. The only thing I could do was some kind internal mourning, but then celebration at the same time. That's why “Malemba” is sweet and sour. It’s a sweet and sour song. It blends all of this, and that's the moment I was in when Gotopo was born. So I don't know if it’s going to be Gotopo as a universe, because I get this question, right? But I know that that's the seed. That's the seed where Gotopo originated. I do believe in a spiritual connection. I know my ancestors can be remembered, immortalized and celebrated like this. So it was personal, but it was also social.

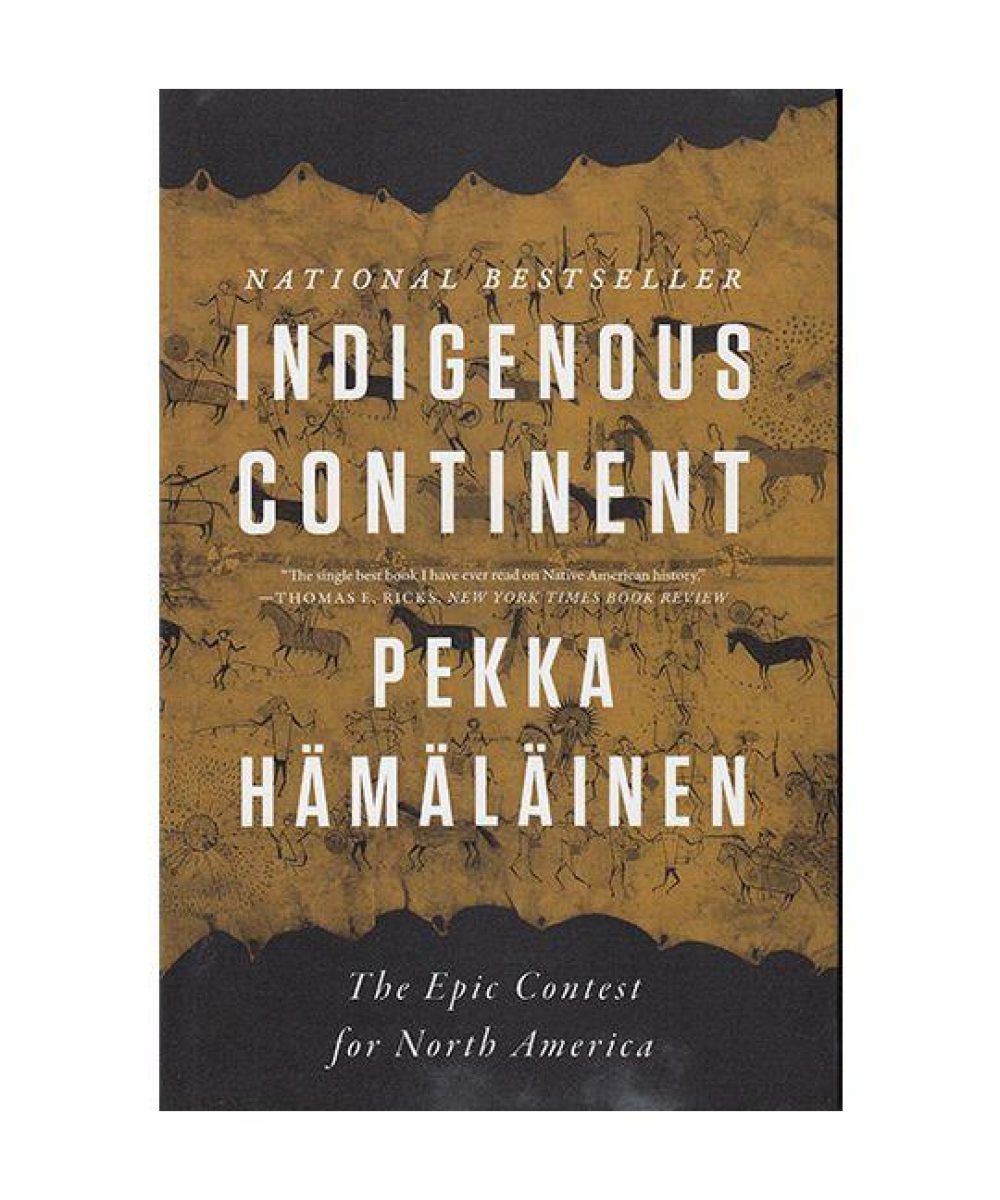

It's interesting to me that you have ancestry both in indigenous Venezuela and also in Africa. I've just been reading a book about indigenous people in the United States. (Indigenous Continent by Pekka Hämäläinen) It’s a telling of American history from the indigenous peoples’ perspective. There's a part in it where indigenous women are marrying and African men who've been brought over as slaves. And it just made me think about certain expressions in American culture, like the Mardi Gras Indians in New Orleans. Deep stuff. But this is your lived reality. How do you think about your ancestors? They come from traditional cultures, but in very different settings and circumstances.

Exactly. And that's the second level of this blend between pain and celebration, because we're talking about two ancestors that already were going through so much, and then they come together to create a new generation. But these two sides, they come with a lot of pain, they come with a lot of suffering. You live to survive, not really live, live. So all of these things we carry with us. And of course, if somebody erases your memory, like Men in Black, then theoretically you're happier because you don't know. I don't want to say happier, but you're happily distracted.

You’re numb.

You’re numb. If you figure something out, of course everyone will react differently to it and process that differently. Lucky for me, I had art, not only to process it personally, but also to share a process that, like I said, I'm pretty sure is not just mine. And funny enough, back in the moment, I felt, “Oh, my God, am I alone on this? Is this like a me thing?” I used to feel, oh, that’s just my story. But then I started to use social media more and realized that there were so many young people, even influencers, that were getting famous on social media, sharing their own process of realizing these things.

Some of them know exactly who they are. O.K., I'm Cherokee. Which is not my case. It's more complicated. But my point is they were getting quite a big community by sharing their experience of their culture, or just starting to learn their own culture, which their parents even didn't teach them because they were oppressed and they were denied. And this young generation said, “No, I'm going to take it. I'm going to go back to my grandparents because they are still practicing it. And I choose as a young person to own it, to practice it, to learn it.”

So, yeah, it was really tough because of the forgetfulness on the one hand, but then also understanding. Wow, that's quite a crazy blend. Two pains and two beauties came together. Yeah, but also, it's like, wow, how brave would you have to be to be creating new futures by coming together like that. And so many questions. In fact, I'm very curious about that book.

Indigenous Continent. Very interesting book.

Amazing. I'm typing it down.

So you say your parents didn't have that curiosity about ancestry.

It was a different time, a different mentality, different cultural situation.

I don't know that many Venezuelan artists. We’ve met and interviewed Betsayda Machado, the traditional group.

Yeah!

I know more groups in Colombia, especially Bomba Estéreo. I know you have a nice connection with them, and that you’ve opened for them. But I’m curious about Venezuela. I know there's a lot going on there right now economically and politically. I follow the news. But do you feel like this is a moment when your generation has more consciousness, that the idea of thinking of yourself as an Afro Indigenous Venezuelan is more of a thing now, more connected to this trend you are finding on social media?

I do feel that. Of course I'm careful not to claim 100 percent that that's the case. Because now we can see certain things. It's not that they were not there. It's just now we get to see them online and find them. So I don't know. But I do feel the winds of time as well. Because when I started to find it online, I could see it’s a modern thing, not an archive of something. It's happening in real time.

I mostly found it first in the U.S.. A lot of indigenous youth doing social media. And then the second biggest community I found is in Brazil. Brazil is crazy. A lot of indigenous influencers, creators and rappers, designers, really, with this very strong need and clarity about what it means to decolonize, for example, in music or fashion. A lot of them are doing very specific work with their own skills and talent. Because growing up in a certain context where you've been culturally washed out, and everybody's supposed to wear blue jeans and white T-shirts, for example. Why?

So these designers are trying to change that. The design is really modern, not your traditional version. It's the young ancestors as I call them, doing what I'm doing in music, but in fashion. Why should I just wear blue jeans and white T-shirt? What if I have a culture? What if I want to dream about my culture?

There’s a lot of this on the African continent too. The fashion industry is just exploding and it does seem to represent an evolution of collective identity.

Let's talk about your music, about this debut EP, Sacúdete. How did you go about making it?

It’s funny because it was not like, “Oh, let's make an album,” and then we made an album. It was magical in sense. Everything started to come together in a way that flourished into an album. So after I did “Malembe,” I was ready for more, and I still had more questions than answers, but that's O.K., because science and art have that in common. And these questions that I had were about many topics: rhythms, genres, so many things. And then as this process was going on, I was also meeting new people, having new conversations. I was in a moment when I wanted to get also out of my comfort zone in terms of musicality. I learned how to produce. I was a composer and a musician, working with paper or a digital version of sheet music, but music production per se, electronic music and such, that was completely new to me. That was also something I learned through “Malembe.”

After that, which was quite a process, more than a year, I was very excited about my newly acquired knowledge and I wanted to create more, so I was doing that. But I also wanted to collaborate, and I started collaborating more and more, so things came together like that. I had a song with a producer called Robot Koh, who was a good match because he works in a zone of magical, atmospheric sonics. He's a German producer who lives in L.A. And that turned out to be very spontaneous. I also worked with Simón Mejía of Bomba Estereo.

I wanted to make sure that we made people dance. That came out very naturally with Don Electron [of the Mexican electronica band Kinky]. We have a few songs with him as well on “Piña Pa La Niña,” “Cucu” and “Sacúdete,” which is the lead single of the album.

Most importantly, on all of the songs, the lyrics and the melody are my work. But I also produce. I never release something where I haven't put my hands on the [mixing] desk. And that's something special because not every artist is doing this. But with these guys, it was very smooth because we communicated well and respected each other's creativity a lot. And that was beautiful.

Talk about the song “Cucu.”

“Cucu,” for me, was a good choice for a first single because I feel like the conversations around feminism can sometimes get polarizing with people, and I found myself wondering why. I mean, it should be a pleasure for everyone to help empower women more, because everyone has a mom, right? Things get polarizing, and I'm like, O.K., let's bring some joy into this conversation. So “Cucu” has some funny, cute, naughty dance floor stories, flirty lyrics, but it’s also very clear. It's like, she's hot, she's beautiful, she's a tropical mommy and everything. But if she says no, it means no. Something I love about tropical songwriting is that it always sounds light and naughty and chill, but there's always, like, some little hidden message inside, like a serious topic. I love that. It's such a tropical thing in the Caribbean. I wanted to write a song like that. I call it positive feminism.

That's great. I see where you're coming from. These days in this country, social issue discussions have become so harsh and unpleasant.

It’s funny because whatever gender or identity they are, people sound as if they didn’t have a mom. You know what I mean? They're offending someone, a stranger's rights. But, honey, everyone came from someone's pussy. It doesn't matter if you're a man. That's the only way to do it. Sorry. Come on.

What about “Piña Pa La Niña”?

“Piña Pa La Niña” is also having this Caribbean tropical naughtiness in it, also following the same principle of the way Caribbean lyrics were written historically and how, because we live in times where, at least in Latin music, 99.99 percent of lyrics are sexually explicit and all about sex. I thought like, O.K., what can I add to that? What can possibly be said? And then I was like, O.K., of course there's still a lot to be said because a lot of those lyrics are 70 percent, 80 percent male written. There's still a lot of non-male perspectives that need to be heard.

So I was like, O.K., I want to write a song about tropical fruits. I love the fact that in the emoji world, the penis is always the eggplant or the banana emoji. That's very clear. Everybody's like, oh, yeah! But when it comes to the vulva, there's not a unified front. So. Papaya. If you're Latin American, you use a papaya or a guava. So it’s the same principle as “Cucu.” This tropical vibe. Like, if you hear it, if I don't tell you this, it's just a fruit song. Five-year-olds can hear it. “Oh, fruit! Papayas and bananas.” And it's very healthy. But if you're an adult, there's a little something else for you.

That's nice. I know a song like that called “Mango.” It's by a Canadian singer, Bruce Cockburn.

Oh, that's amazing. “Mango.” I’m going to look for that.

What’s your performance life like? Do you perform with a group?

I see myself developing kind of the way an artist like Bjork has done. I can perform alone. Right now, for me, it's very important to grow sustainably, both artistically and financially. Maybe it's funny that I bring that to the front right now, but I like to be honest about it because people want to keep things very dreamy and such. But for me, everything is reality. Reality.

But it goes together because it’s not only money. I'm able to do a lot with less, right? So, for example, when I opened for Bomba Estereo, it was not the most minimalist version, which would be alone. I had a DJ with me, but Simón [Mejía] was like, “Whoa, we didn't see the video alone. It was you, and you aced this thing.”

And I'm like, “Dude. I mean, if I wouldn't allow myself to go through that, I wouldn't know.” It was 3500 people, and there were also cameras, but musically speaking, I had just a DJ. So I do see myself doing more. There's no limit for how I imagine myself performing. I would love to have a choir of dark Afro-indigenous voices behind me. And I will. The moment will come. Just sit down and wait. But right now I have performed mostly with a DJ and solo. When I perform solo, I use a percussive sampling machine where I program my stuff and perform. It's something between live music and an electronic music performance. I have my Midi controllers, I have my synthesizers, I have my stuff, and I perform like that.

I focus more on just being with people, sharing my energy, my body, being close to them. And then I also have performed with a band, mostly in Berlin, mostly locally, and it's also been really incredible. So I've tested all of those magics and each one of them is amazing in its own way. I'm in a moment where I really want to try stuff.

That's fantastic. Well, I look forward to seeing you live in any of those formats. Thanks so much for speaking with me.

Thank you. Bye bye. Have a lovely one.

Related Audio Programs