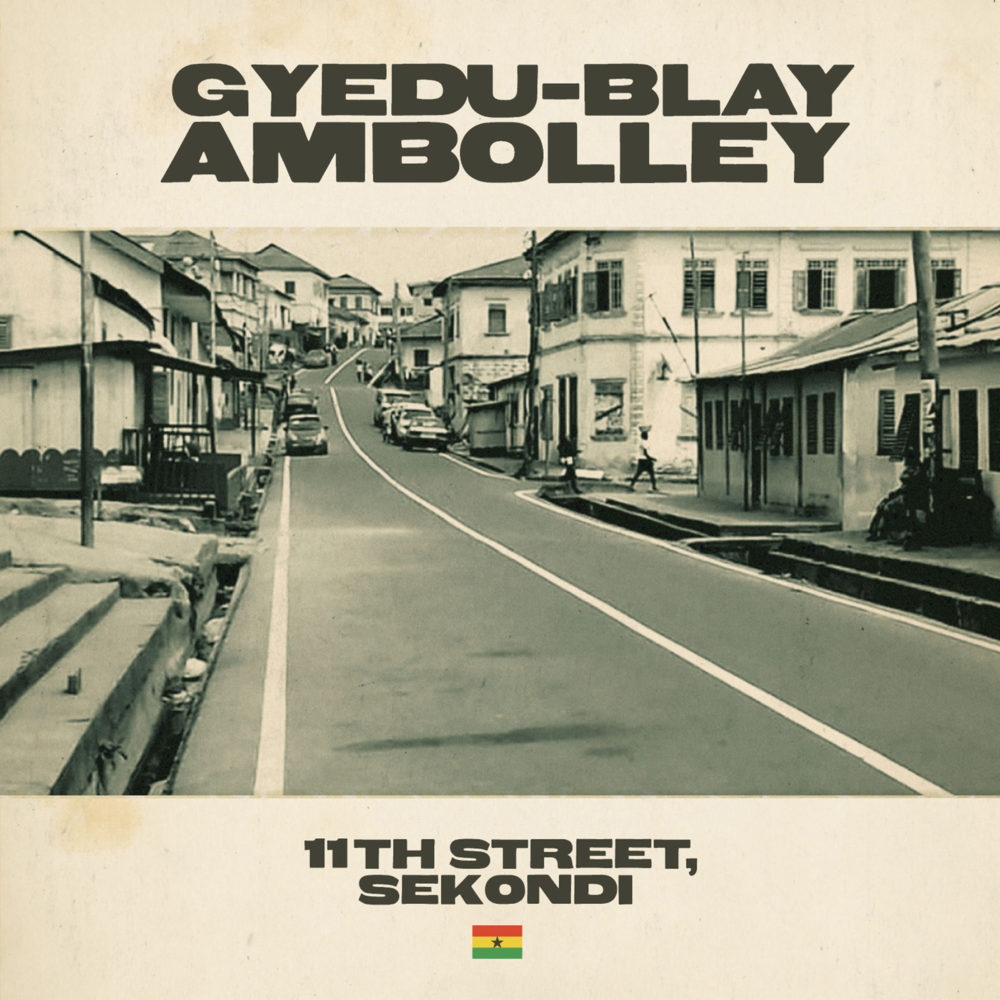

Ghanaian composer, bandleader, singer and saxophonist Gyedu-Blay Ambolley is a legend of West African music. A pioneer of highlife, Afro-funk and Afro-jazz—and, by his own account, the world’s first commercial rapper—Ambolley enjoys a unique place in the pantheon of African music. Afropop spent time with Ambolley in Ghana in 2013, and watched him in action in nightclub and recording studio settings. As 2019 wound down, and we savored Ambolley’s 12th album release, 11th Street Sekondi (Agogo Records), Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Ambolley by telephone in Accra. As you will see, Ambolley is an old-school gentleman, but one who has maintained an enduring mantle of hipness. Here’s their conversation.

Banning: Nice to talk to you again. Can you hear me well?

Gyedu-Blay Ambolley: Yeah, I can hear you.

Good. I am going to start with a silly question. I'm never sure what to call you. Gyedu [JAY-doo]? Blay? Gyedu-Blay? What do you prefer?

It’s Gyedu-Blay, or sometimes Gyedu, or sometimes Blay. It’s all O.K..

It's all O,K. Well, I'll go with Gyedu! This new album, 11th Street Sekondi, is wonderful. Very strong work.

Thank you.

I think about you having started all the way back in 1973. I was just looking back to the long interview we did in Accra in 2013.

Yes. Some years back.

In that interview, you go over your long, great career, and it hit me just how impressive it is that you're still doing such great work. I think this new album is among your best. How do you feel about your creative state after 55 years of making music?

I feel good. The reviews that are coming from Germany, France, Holland, the U.S. [including one on afropop.org] have all been good. It makes me happy that people are appreciating the work that I put into this album.

Did you record this in the studio where we visited you in Accra?

Yes. Some of them were recorded in that studio. Then one or two tracks were recorded in my own studio.

I remember the studio where we met. It was fairly small. Did you record everything in that? Even the brass?

Yes, the brass and everything. Everything was manually recorded. Brass, guitars, bass, everything. A lot was put into this album.

How long did it take?

It's taken close to two years. I remember laying down the tracks, taking it home to listen back and making corrections that needed to be made to make the album sound the way I wanted it to sound. So when it's out of the studio and everything, it's been about two years.

The work shows. There is a great variety of styles there. Tell me about the song “Brokos.” To me it sounds like a combination of classic highlife with a little Congolese rumba flavor to it. Really a sweet mix.

You know the different styles you hear on the album, it's all coming from the basis of highlife. If you're talking about rumba, you're talking about calypso, other styles of music, the Caribbean touch—the mother of all of them is highlife music. Two things make highlife. First, the basis of the clave rhythm—1 2 3 1 2. That's the male side, and the female is Ba Ba Ba da-ba-le-be-na, Ba Ba Ba… These two formations are in every dance music in the world. Music coming from India or South America or America. Any dance music has these two forms of idioms in it. So the rumba and the calypso and all the other kinds of feelings that you get on this album, all of them have these basics in them, from highlife. So there's the rumba branch, and the salsa branch of highlife. Highlife is the tree. It includes all these kinds of dance music.

What makes me think of Congo in that song “Brokos” is the guitar solo. Who is playing that guitar?

I have two guitar players. One is Dominic Kwakye, and the other is Owureku. These are the two guitarists I use. If one of the guitarists is not there, the other one plays. All of them have the feeling of the style of my music.

I really like the song “I No Dey Talk I Do Dey Lie.” There's a strong message there. Even a political message it. I remember you talking about how music has to have a message. So what inspired the message in this song?

Any time that I compose music, I look at the do's and don'ts of my people. What is happening in the society. And anything that I see that it is not in conformity with our culture, I try to speak up to enlighten my people. You know every place has a culture and we mustn't forget our culture. You go to England, they have theirs. Go to South America, they have theirs. Go to India… So we have ours. And we have to stay close to what our ancestors left us.

For example, take the song "Black Woman.” I see that most of the black women now are changing themselves into the European ways of dressing. Most of our women are wearing weave wigs and all of that, and I'm trying to tell them that "Yes, you are a woman. You're O.K. to do all these things, but you don't have to forget about your roots. Because you have something to offer the world. You have something to show to the world. And you don't have to forget about that."

Or talking about another song like “Ignorance.” Ignorance is making us do so many things that we mustn't do. Because if you are ignorant, and you are not informed, you won’t know if you're doing the right thing or the wrong thing. So these are the things I see happening around me. I know that music is there for entertainment, but we also have to use it to teach the people. If they are forgetting themselves, then we have to bring them back to reality.

When you talk about people reaching out to the West for fashion, or style, or even music, do you think that is that different than what was happening in the 1970s? What makes this time different compared to when you started out?

Some years ago, most of my music was in the same vein, talking about pan-Africanism and misseducation and all that. Because we have to know ourselves as a people. Likewise, if you travel to any country, you find they know themselves. So we have to know ourselves. Because of the colonization, there are many things that have infiltrated into our culture that are making us sometimes forget who we are. So I tell them, “Yes, infiltration is O.K., but still, we have to be ourselves. And the one thing that can bring us together is our culture. So the hairstyle, the dressing, the wearing of eyelashes and fingernails and all those kinds of things—you can do them, but we need to fit them into our culture instead of moving over there away from our culture.

This is kind of a universal message. You say that you've been singing about it all along. But is there something about this time that makes that message even more important, with technology bringing people so much more in touch with the outside world?

It's something that certainly did not start from today. It's something that's been going on for more than 400 years. It started long time ago. It's bigger now because of TVs and videos and phones that have lots and lots of information on them, so it looks like it is growing. We're moving deeply into the outside world. And sometimes it depresses me, because I think that, “Yes, we are going into the outside world, but we are a people and we must not forget who we are. When we go travel from here to the outside world, we have to show to the outside world what we are, rather than showing the outside world how we are copying the outside world.” So all these things sometimes come back to me, so I believe that, yes, I have to tell my people and enlighten my people and let them know that we have something that is durable, and that we have to cling to.

The world has become a global village, but still, everything that belongs to this world comes from somewhere. And everywhere that it comes from has a culture attached to it. So we mustn't forget ours. Now black people are spread all over the world, still, we have something that belongs to us that we have to let the world know and experience it.

Absolutely. I think that artists of your generation have a special appreciation of that because you lived through the process of coming out of colonialism and into independence. To me, the greatest music is the music that came up in the '60s and '70s, when people were finding that balance between international sounds like reggae or rock or jazz, but also bringing strongly into it cultural ideas that had been held back during the colonial times. African culture was just coming forward in this powerful, beautiful new way. And it's great that you stand for that kind of feeling now too. Because I think it's needed.

Yes. It is totally needed. When I travel from here and go outside, whatever I'm doing, it is based on highlife. When I'm playing in a jazz form or in a Caribbean form, it's always highlife. So this is what I have to portray to the world. If you are a painter, or an engineer, or anybody that does anything creative, yes, we have to let the world know what we have. Where I came from makes me strong. Highlife music is something that will bring you to the dance floor, will make you forget your troubles and feel good about yourself. Dance the night away and all that. So to me, highlife music is a music of unification. It brings all people together. So that's what I'm carrying with me.

Beautiful. Speaking of highlife, I really like this song “Sunkwa.” That's classic straight-up highlife with you kind of rapping over it. You talk about different kinds of highlife. How would you describe that particular song terms of its highlife style.

That's the style of highlife that our elders, our ancestors left for us. You know, the sunkwa formation is the highlife of Ebo Taylor, the Broadway Dance Band, E.T. Mensah and all these – that's the style of highlife they were playing. So me growing up among them, I know what they were interpreting. So I felt like I have to also bring that out so that the younger generation will know what was there. That sunkwa highlife is the music that our ancestors were playing, and I love it.

How could you not? It’s so beautiful. I want to go back to “I No Dey Talk I Do Dey Lie.” Who are you talking to in that song? Who is “Dey?”

Well, these days there are a lot of things going on with the politicians and those in the churches. So when I say, I know they talk, I know they lie, that means when I talk I don't lie. When I'm saying anything, I say the truth. But some people in the political arena are extorting money from the coffers of the government for their own personal use. So these are the people I'm talking to. I say to those who are doing that, we will catch you. We will chase them and take them to jail if they embezzle government money. And there are pastors extorting money from poor people. These are all the people I'm putting in one basket and advising them that whatever they do, make sure you do it well. If not, and you get caught up, we will check you, and if you are at fault, you will go to jail. So it's a warning I'm giving to those in the political arena.

That sounds like a global message. The world is certainly full of politicians who lie. As you know, we are dealing with that here in America as well…

Yes. That is true. [Laughs]

Let's talk about this very interesting song that you did with participation from Wanlov the Kubulor, “Who Made Your Body Like Dat?” Talk about that song.

You know, women are the opposite of men. Men adore women. So sometimes you have a beautiful girl or woman with a nice-shaped body, a nice face, a nice nose, beautiful eyes. So we sometimes ask, who made your nose like that? And most of the time it's, "My mama made it like that." Who made your shape like that? "My mama made it like that." So it's an adoration to women. So then I brought in Wanlov the Kubulor to put his style of rap into that song. The music sounds like funk, a funk style of music, but it's my creation. And I thought of doing something like that to bring it into highlife a bit, and then you funkify the music, and you get that sort of difference. So I invited Wanlov to put his kind of rap into it, and people love it.

I bet they do. He's so talented. And I gather you also appeared on his most recent record, the FOKN Bois, the album Afrobeats LOL. You appear on the song “Abena Repatriation.”

That's right.

I'm interested in the conversation between generations of musicians in Ghana. Wanlov and Mensah are kind of in a category all their own. But they are part of this new generation. There's this new genre of music now, whether you call it hiplife or Afrobeats or whatever, you sense that it has a new feeling. But it seems like these young artists in Ghana give you a lot of respect. They look up to you. Have I got that right?

Yes. Definitely. Because the younger ones when they meet me or see me at a function or festival, they always look up to me. Because they know that the formation of music that they are doing, the rap, they know that I'm the one who started it. You talk about Reggie Rockstone, Reggie knows who I am. Reggie's father was my friend. So when I came back from America, Reggie's father used to talk to me about Reggie trying to come into music. But by that time I had done my rap music, the one that came out in 1973.

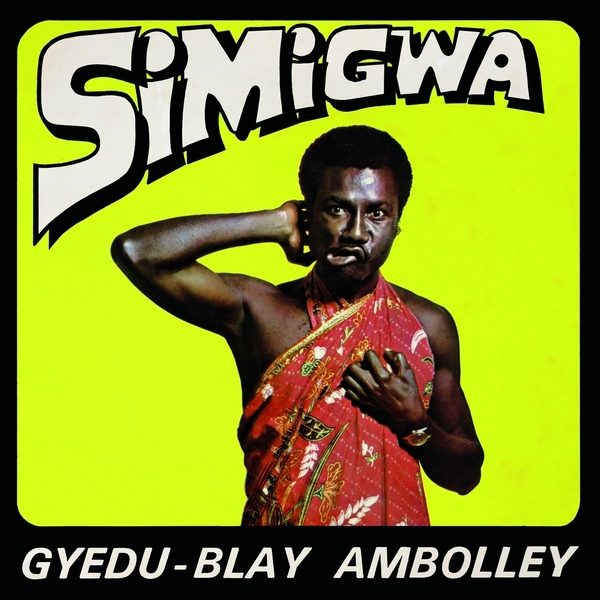

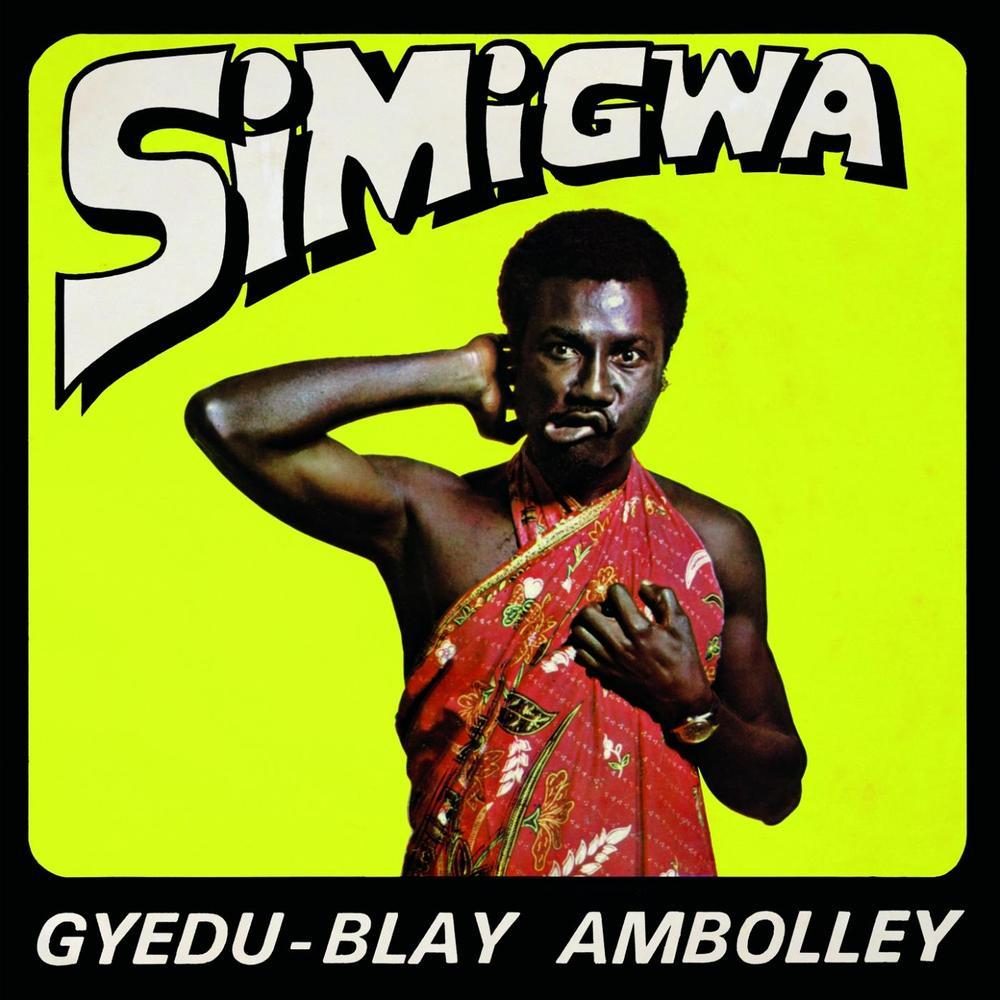

Yes. “Simigwa.”

That's right. So they have total respect for me for that. And I appreciate it. Although the style they are doing is a total deviation from our music and our heritage. They play more with the computer and the sounds that are in the computer rather, and now they call it all these new names. They are not closer to Afrobeat music and Afrobeat sound, but they are calling it that.

The problem is they don't know the language of music. They haven't studied the rudiments of music. Composition. Arranging. They haven't learned that. So they are capitalizing on what they can do with the computer. I think they need to learn.

You said something like that when we met in 2013. Do you think there's been any change or any progress since then? Is there any evolution, or is it pretty much the same story? And if so, are you worried that knowledge of music theory or how to play instruments and that sort of thing is not being passed on and could get lost to future generations?

Yes. Because music is a language. And if you know the language, anywhere you travel, you can deal with other musicians. Because you understand the language. These younger ones often don't know the language. And they have to learn, because in my time, we were going to our elders to learn the rudiments of music. We learned guitars, bass, horns, and musical arrangement and all that. So whatever I'm doing now is based on something that I learned before. So when I go to compose music, I know what I'm doing. But the younger ones don't have that. It's necessary for them to come so we can teach them. They can't just make music using what's in the computer.

Let me ask you about one more song, the last song on the album, “Woman Treatment.” To me, it sounds like another nice blend of highlife and funk. But you have a line in the lyrics that says, "If you give a woman a sentence, she's going to give you a paragraph." What are you getting at in this song?

I'm trying to say that if you have a woman and you have respect for that woman, she's the one who will love you. If you give her a house, she will make it a home. If you give her some foodstuffs, she will cook you a meal. If you give a woman sperm, she will give you a baby. So it's a give-and-take. Human life. So if you give a woman in a sentence, she will give you back a paragraph. And if she disagrees with you, then it becomes a long process. But I'm trying to say that we’re living together. It's a give-and-take.

When we met last time, you spoke about a lot of different kinds of traditional music that you grew up with—Fante, Ewe and so on. You showed great knowledge of traditional music in Ghana. But one of the important things I think about in highlife is that the music is not tied to any one ethnic group. It can bring in those elements, but it's for everyone, and it has that quality of unifying people as you said. And I think that is something that people like about this new African music that the kids are playing now. It has its problems, but it does have that quality of bringing people together. It's not tied to any specific ethnic tradition.

I've done some studies. In Ghana, we have people of different tribes and different tribes have different forms of music. Sometimes if you go to perform and you play music that belongs to a certain tribe, it's only those people from that tribe who will dance. If you play the Ashanti adowa, it's only the Ashantis who will get up and dance. If you play something from the West, like kundun, it's only the people who know how to do that dance will get up and dance. But the moment you play highlife, all of them will forget about their tribal music and come together to the floor. That's how highlife is music that unifies the people. The moment highlife is played, the elites and everybody will come together on the floor. That's why it's such a powerful music. This is how I knew that if I incorporate this into my music and travel with it, people everywhere will love it. The style, the rhythm, everything in it is for everybody. So when we play in France, Belgium, Germany, we get the same reaction.

A great idea. You said something I remember last time we met, something about you were born with the same 10 fingers, and when you die you will take the same 10 fingers with you. And then I think you said, "I have never seen a hearse with the baggage rack."

[Laughs] Yes, because people are trying to accumulate worldly things. They want to have a big house. They want to have all these things. But when somebody dies, all these things they've accumulated, they leave them all behind. You never see a hearse going to the cemetery with things in the boot. I've never seen that before. We can accumulate so many things, but at the end of it, we leave them all behind.

Better to leave behind great music, which is what you're doing, and I applaud that.

Thank you.

I have been reading about highlife lately, and I went back to an interview I did with John Collins some years back. And he said an interesting thing. He said that highlife music was so much about the band, about people making music together, like a family. And that that feeling transcends to the audience. One thing he was unhappy with about the new music is that so often it's just one person in a studio with an engineer. He felt like that communal aspect of the band, the family, was getting lost. What do you think?

It's true. Highlife is a family music. It's you and your cousins and your brothers, everybody coming together to portray something for an audience. When we play music for the audience, we want the audience to feel what were doing together. Music, lyrics. We’re sending out information. If it's like that, it means that everywhere you perform, people will listen to you. They will get involved with your style of music. But sometimes, there are musicians who become a little selfish. They cut themselves off from the audience because they learn so much music that when they are on the stage to play, they want to show everything they've learned. So instead of having a dialogue with the people there playing for, it's like they're trying to impose something. The moment it happens like that, then it becomes a little rigid.

Music is for sharing. The moment we stand on the stage, we are trying to share with the audience. The message has to move between the musicians and the audience. So when it happens like that, you and the audience all become one happy family and enjoy it. When I was in America, I went to jazz clubs and I feel that often the jazz musicians are more into themselves than into the audience. I think that needs to be changed. Highlife can do that.

Well, thanks so much for talking today. We send greetings and best wishes for the new year from everyone here at Afropop. We are so glad you're still out there making great music, and we look forward to seeing you on the side soon.

Thank you very much. And I'm looking forward also. We've met a few times in Ghana. But I want us to meet musically.

I would love that. That would be a great pleasure. We'll stay in touch.

Yes we will. All the best to you and your family.