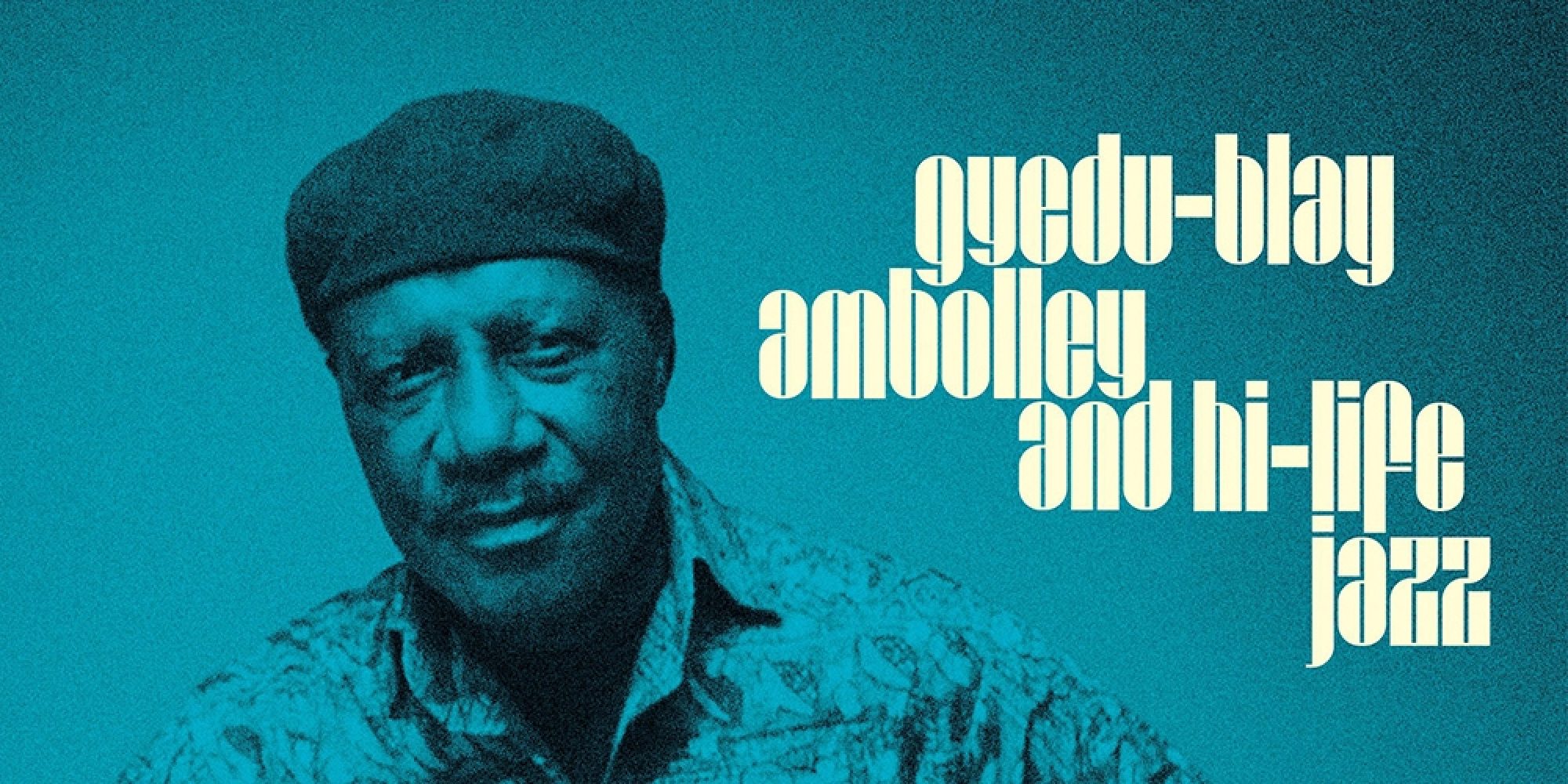

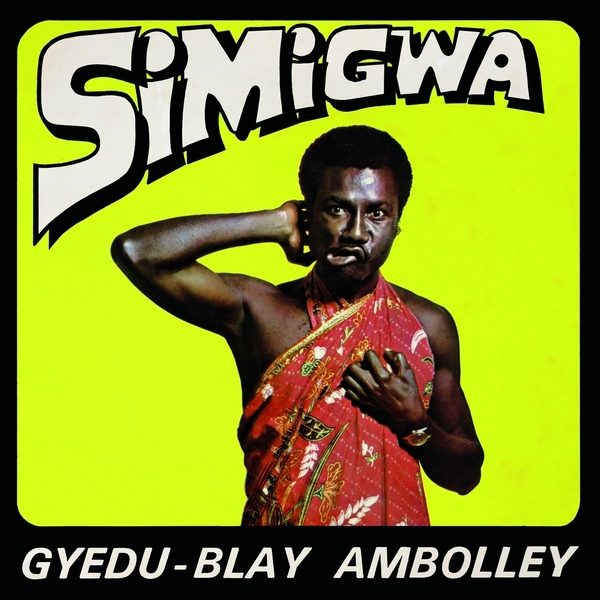

Gyedu Blay Ambolley is a living legend of West African highlife, Afro-funk and Afro-jazz. And the good news is, he’s still making fantastic music. His new album Highlife Jazz finds him and his band in top form. There are covers of jazz classics, “Round Midnight,” “All Blues,” “Footprints” and “A Love Supreme,” all reinterpreted with a distinctive highlife swing. The album is a joy to hear, among this veteran’s very best work. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Ambolley in Accra as he was about to set out on tour in Europe. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Gyedu, great to speak with you again.

Gyedu Blay Ambolley: Nice to talk with you too. It's been a while since we last met here.

Yes, almost 10 years. How’s life in Accra?

Accra is O.K., but it's been raining lately. We are getting prepared for the tour to promote the album.

Where are you going?

We'll start in France and then go to Holland, Denmark, Sweden, and then we’ll come back to France. Just a short tour, five countries.

Fantastic. I am really loving this album. I've enjoyed everything you've done recently, but this one is special. How did you come up with the idea of doing famous jazz songs in a highlife mode?

You know, I lived in America for sometime, and I got myself familiarized with the jazz music that's played over there. But many a time, I look at the audience and these jazz players, and I see that there's a gap in between the audience and the musicians. The jazz players are so busy in expressing what they've learned, sometimes they get into themselves so far that there's a gap between them and the audience. And I thought, “No, there has to be something that connects the audience to the jazz players.” So I thought that highlife would do the trick. So I did a few experiments back in the U.S., and I saw that, yes, that's what's missing.

Jazz itself came from Africa, and I see Africaness in jazz performances. So I said, "O.K. man let me experiment with the jazz sector, adding the cadences of highlife." I'm trying to open a new door. Not yet, but I'm trying to enter the American main stream. That's why I chose "All Blues,“ “Footprints,” “A Love Supreme,” “Round Midnight.”

It's interesting that you've done this, because when you think about the history of jazz, it was originally dance music. It was only in the ‘40s and ‘50s when bebop came in that it kind of stopped being dance music. A lot of older jazz fans didn't like that. They thought, “We’ve lost something.” But you've managed to bring back the dance music era of jazz via highlife. You talk about songs like a "All Blues,“ “Footprints,” “A Love Supreme.” Man, I grew up with those songs, and you've managed to make them fresh. What was your process like? How did you arrange these songs?

It took long time experience. With highlife itself coming from Ghana, and our elders who were playing highlife, like E.T. Mensah and the Ramblers—all these people were experimenting. For example, on the instrumentation side, when the military came in with the trumpets and trombones and everything, they started to jazz up highlife.

That's right. Jazz was in there from the start with highlife.

Exactly. So that was at the back of my mind, and going to America where the jazz itself was happening, looking at the place, I was thinking in my head, "When I listen to the melodies and the chords, whether it's 12 bars or 16 or 32, I can differentiate where the arrangements are coming from.” That gave me the idea to do it this way, even though it's been done that way. I know that all the songs have been recorded many times. So if the people from South America and the Caribbean can take them and play them in a salsa format, then I can also play them in a highlife format.

That makes perfect sense.

That was the idea.

When you talk about spending time in America and absorbing jazz here, are you talking about recently or back in the past. I know you've been here a number of times.

I came to America in 1988. I was in New York for about six years, and around ’94 I left for Los Angeles. I love the vibrancy of New York and jazz, when you go to Harlem and downtown. That was the place where I saw Jimmy Smith for the first time. He was playing at Fat Tuesdays. I went there with Jimmy, who was with Stanley Turrentine and Grady Tate and Kenny Burrell. I was checking those guys out when I was back in Ghana, and here I am seeing the face-to-face. Whoa. I was really, really happy to have met them. And when I went to L.A., I met Art Farmer, George Duke… All these guys came through to jazz festivals.

Great stories there. But let’s also talk about the songs you wrote on this album, for instance the opening track, “Sankumagye-Love Life.”

Listening to jazz for such a long time, I see that there's a connection between jazz and highlife. Whether it's the instrumentation or the melodies or the compositions or arrangements. All of that. I've been saying that for a long time. Back in the days, Ebo Taylor and all those guys were experimenting with highlife and jazz cadences. So the idea was right there. So after listening to that for a long time, it was in the back of my mind.

I’m glad you mention Ebo Taylor, because I really hear an echo of him in the brass arranging on this song. It's beautiful. Ebo is amazing. He was a real pioneer in that department. But I like the way you nodded to him in this track.

Oh yeah. Ebo is my senior in the music. I started following him when he was just in the Stargazers Band back in Kumasi. And when he came down to join the Broadway Dance Band, they were experimenting. That kind of experimentation was at its peak.

This jazz element has always been there in your music, but on this album you've really put the focus on it in an interesting way.

Yes, there’s a reason I added “Round Midnight” and “All Blues” and all those things. But I wanted, apart from playing the American repertoire and giving it a different feel, I also want them to hear what we do apart from those compositions. That's the reason for the original tracks.

I hope this record gets heard by a lot of American jazz people, because I think they'll love it. Tell me about your band. I remember when we saw you at 233, the jazz club in Accra. Is that still there?

Yes, it's still there.

I remember you had a great band, but I particularly remember a trumpet player you had. He was excellent. Are you still working with those same guys?

Yes. When I came back from America, I said I need to put together a band. So I went around listening to all these young guys playing, and I saw that many of them had potential, many of them. So I started to choose musicians that I wanted to work with. I chose that trumpet player and a saxophone player. I chose a bass player and a drummer. Keyboards. All of them have been with me since I formed the band.

Well, that helps to explain why they sound so tight and so comfortable. What is the trumpet player's name?

Kuku.

And that's the band you're taking on tour.

Yes, we are eight in number. I'm looking very much forward to bringing the band to the United States. I think we need to come to America to share with Americans what we've been doing in Ghana, West Africa.

Amen. I'm working with a colleague on a documentary about funk music in Africa in the ‘70s. If we get this thing off the ground, we're definitely going to get you involved, because you have lived that history. The idea originally was to tell the story of the 1970s, but now it's moving to a link with young artists today. We’ve been advised to to start with some of the well-known names of today in order to fund this project. So that made me think of asking you this. When you look at the current crop of young Ghanaian and Nigerian popular musicians, who are being so successful, what do you think they are carrying forward from your generation, and Ebo’s generation? Do you feel like they are leaving things behind, or are they transforming it a new way?

For me, I think they've left the tradition behind. The young artists now are calling themselves dancehall artists. Dancehall. Everybody is doing dancehall, singing in Jamaican patois, and using computers. They are not experimenting the way we were as musicians. They are depending too much on computers to give them their background, and a chance for them to sing patois dancehall. They are proud to say, "I'm a dancehall artist. I'm a reggae artist." I keep telling them, reggae and dancehall are the music of the black people who were sent to Jamaica. But we have something here we call highlife. That's our heritage.

So if you leave our heritage behind and copy what comes from Jamaica, then are you being real? I keep telling them this, but it looks like they are focused on making money. So there are a few that are bringing the tradition forward, but most of them think, “If I'm making money, what else do I need?” But I tell them that if you do music and the music is good, the music will always stay young. And the music will always bring you money. Look at the population of the world now. You can sell your music throughout the world. I think that the market is actually much better now than before, because of technology. So this is the time we need to tell the world and show the world what we have, because every country has its music.

That makes a lot of sense to me. I hear what you mean about dancehall, but what about the artists who are trying to present a new African identity with hiplife and Afrobeats, with an “s.” There is a little bit of highlife rhythm in that music. What about those guys? They are at least trying to make a connection.

Yes. Like I said there are few who are getting closer to our heritage here. But they need information. They need to know more. They need the educational side. That will make them stronger in portraying what we have in Ghana and in West Africa. As you say, there's a little bit of highlife in there: “ka ka ka ka ka.” So they're using the highlife clave rhythm.

They check that box, and they're done. That’s how you see it?

That's it.

It's interesting. We've had this radio show for 35 years, since 1988, and we're at the point now where we're trying to figure out how to pass along what we have to the next generation, because the history is there in what we've done, histories of all kinds of African music. But it's hard to make that connection with this current generation. I think we have an important role to play in helping young artists understand what's gone before. But we need to find leaders who understand this mission, to make the bridge, like you're doing. It's a challenge. If you know anyone who wants a career in media and are up for a challenge, send them our way.

The challenge is very big. I'm always trying to experiment myself. My style of music, my arrangements, my compositions. When I go to Europe, we have these sessions where I'm telling them, “This is our stuff.” One thing that Mobutu Sese Seko did that was good is that he decreed that 75 or 80 percent of the music that was played on Congo had to be Congolese music.

Yes that is one thing he did right, and it did result in very original music.

That's what we need to do here. Because in Ghana we have so many radio stations now, but what are the radio stations portraying? All of them are doing the same thing: dancehall and all these things. I keep telling them anytime I get interviews, "Hey man, we have our heritage. And we have to allow the world to see and hear our heritage.” But you know, it’s not lost. There are some few young ones there that are trying to look up and get the information so we can move on. We need that. I always say that highlife is in every dance music in the world. If you take salsa, there's highlife in it. You take jazz, there's highlife in it. You take funk, there’s highlife.

It's all one big family, and that rhythm is like a backbone.

Right. It’s deep history

You get a lot of respect from young artists, don't you?

Oh yeah. Anytime they see me, they know there's a senior man coming.

And a special one at that. It's great to talk to you. You keep telling them, and get your band over here to America. We’re here to get the word out.

Hey man ,I trust you. Because you've been at the back of whatever is happening in Africa for a long time. And you're still there. So kudos to that.

Same to you. Have a great tour.