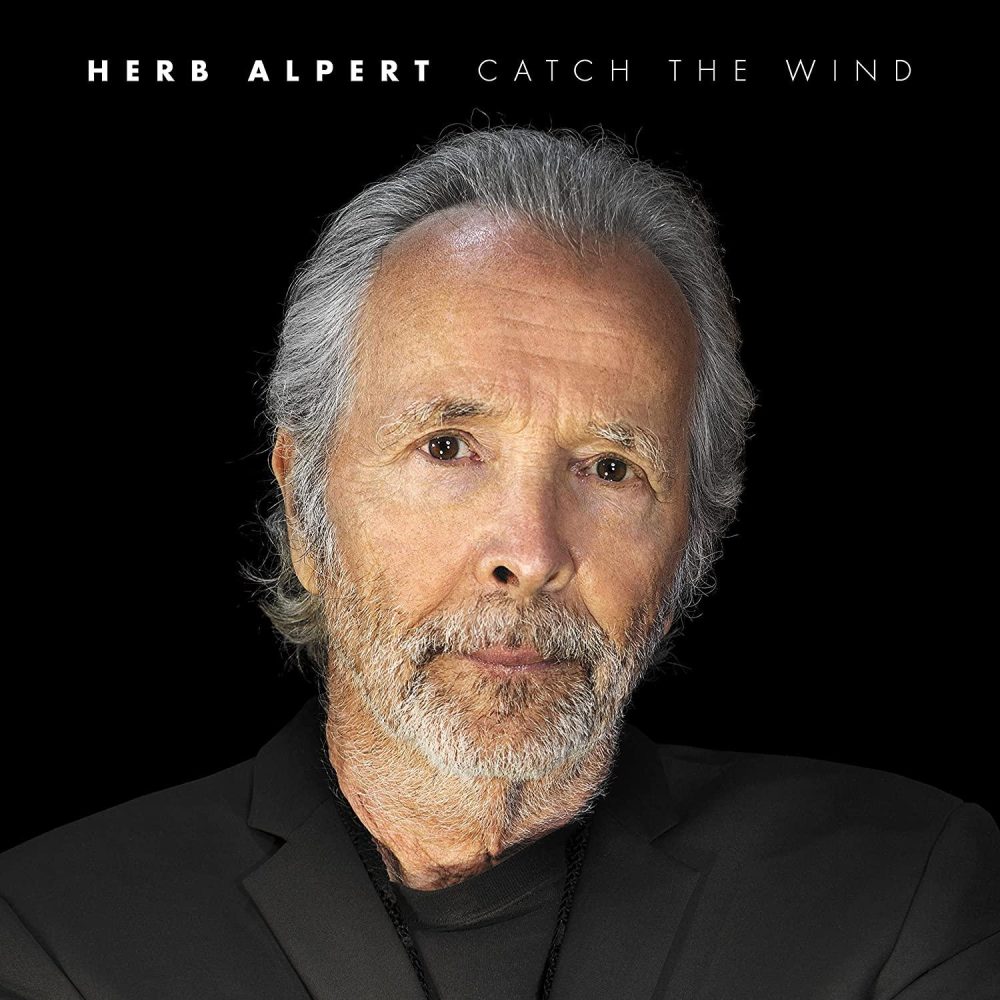

At age 86, Herb Alpert has just released his 48th album. Catch the Wind is a sharp set of originals and famous covers—“Eleanor Rigby,” “Yesterday,” “Smile, “America the Beautiful.” A defining ’60s vibe has coursed through Herb’s work during all sorts of phases since the legendary reign of the Tijuana Brass (1961-70), and it still shines through on the new album, from the buoyant samba of “Brazilian Moon” to the perky quasi-reggae of “Fantasy Island,” both tunes co-written by Jeff Lorber. With the album out, Herb is getting ready to go on tour with his wife, singer Lani Hall, and their backing trio. He is also continuing to paint and sculpt. In a word, the man is unstoppable, not so unlike Afropop’s own octogenarian host Georges Collinet, who, by the way, used to broadcast Herb’s 1965 song “A Taste of Honey” to 1.5 million listeners in Africa every morning for decades. With all this in the air, Banning Eyre and Georges and Herb all got on a Zoom call for a chat. Here’s how it went down.

Herb Alpert: [popping up on the screen] It works. I'm amazed.

Banning Eyre: Good morning, Herb. How’s it going in L.A.?

It's overcast at the moment. It's been weird mornings. Until we straighten this thing out and get everyone healthy.

Have you been affected by the fires?

Not this fire, but the last one we were. We almost lost our house on the last one. We got extremely lucky.

That's terrifying.

It is terrifying. The thing was like a foot from our living room. The firefighters came in because a neighbor had beckoned them, and they saved us. They put out this little wooden porch we have right before you enter the living room. It was on fire. Yeah, man, we thought we'd lost the place.

Crazy. Sometimes we remark how bland our climate is here in New England as the rest of the world drowns and burns. Anyway, thanks a lot for taking time to talk with us, and for making this album. It has a vibe that takes me back to the beginning, when I was a kid mad about the Tijuana Brass.

You know, I never have a master plan when I make an album. I just have a bunch of songs that haunt me for whatever reason. There are a couple I redid here. I just like playing. I wake up each morning thinking about how I can improve on the horn. Because you never get to the place where you think you've got it covered. Playing an instrument is an ongoing process. You never get to the end product, and that's the beauty of it.

I remember that the first time we spoke you said that you are a better trumpet player now than when you were a superstar in the ‘60s. How is that the case?

Well, you know around 1969, 1970, I went through a divorce and I was having a heck of a time playing the trumpet. I was not able to get the first note out properly. I was sputtering through the horn. Luckily I met this trumpet teacher in New York City. His name was Carmine Caruso. He was known as the troubleshooter. He used to teach musicians from all over the world, and the beauty of it was that he never played trumpet a day in his life. He played saxophone. He played violin. But he had the art of teaching.

So I called him and met him in New York one night. I was staying at the Sherry-Netherland in New York. So, he came and we chit-chatted and I tried to play a little bit for him. I said, "What do you think I'm doing wrong?" And he said, "Well, it wouldn't help if I told you. It might just frustrate you. Because you've got to do these certain things that might help you."

And I said, "Yeah, but I'd like to know what I'm doing wrong." And he said, "I really can't tell you." So I ordered some drinks. I fed him a couple of martinis and two martinis later I said, "Carmine, what am I doing wrong?”

And he said [slurring], “You’re trying to play with your lips open.” [Laughs] The point is, in answer to your question, I was asking him, "Do you think it's the mouthpiece? Should I change trumpets? Should I change my setup?”

And he said, "Let me tell you something, kid. You are the instrument. The trumpet is just a megaphone, just an amplifier. It's you as an artist." And that was the big, big ah-ha for me. It took a while to get my mojo working again. It's interesting. I do have my own sound. I've heard that from lots of people. I have my own identity. But I started thinking, wouldn't it be interesting if you had a show and you just put one trumpet on a table or a chair and you called Miles and Al Hirt, and Louis Armstrong was still around, all the people that you recognize, and have them play that same trumpet and the same song. And you'd see how different each one would sound. I mean dramatically different.

What a great idea. I’d have loved to see that.

I always try to tell kids, you're the instrument. Let that sound come from inside.

BE: I see that Georges has joined us now. He’s down in Lewes on the Delaware coast.

GC: That’s right. Delaware.

We won't hold that against you.

BE: So Georges, we're talking about the new album.

GC: A great album by the way.

BE: Yes, we’ve both been listening to it. I am interested that you picked two Beatles songs to cover. I particularly like what you did with “Eleanor Rigby,” turning it into a kind of meditative bossa nova. How did you come up with that?

Well, I start by not thinking. That's the way I start. It's just a song I always liked. My goal has always been: If I can take a song people recognize and do it in a way that's a little different so it doesn't sound like everybody else's version, that's a big win for me. So I was playing with Eddie Del Barrio, my dear friend from Argentina. He came up with this kind of feeling that gave the song a different taste. It was a nice way of presenting the song. We manipulated it and worked on it for a few months before we came up with this particular version. But I like it a lot. It's meditative. I always think that if it's fun for me to play, it might be fun for some people to listen to.

BE: You ended up with two Beatles songs on this album, which definitely heightens the ‘60s vibe. Is that just the way it fell out this time?

It's the way it fell out. I had about 35 songs hanging out in my computer that I fooled around with. I happened to pull out my flugelhorn that I hadn't played for a while, so I played the flugelhorn on "Yesterday." It's a beautiful melody. And it's a song I think people relate to because it's about yesterday, what we were doing yesterday. Can we get back to some of that? We don't want to get back to all of that. We don't want to live in reverse. But yesterday was a little bit more magical than what's happening now.

GC: Why did you choose the flugelhorn for this song, Herb?

It just has a really lovely sound to it. It's a mellower sound than the trumpet. And it was a challenge to see if I can have fun playing it. This flugelhorn I played in that song—I bought it in 1950 for $300.

GC: That was expensive back then.

Well, it was made in France. It's called a Cuizone. And it's a very popular type of horn, but in those days, it didn't cost much money.

BE: Let's talk about some of the songs you wrote for the album. Most of them are co-written with someone else. How about "Fantasy Island," which you wrote with Jeff Lorber. It's got a nice reggae feel about it. How do you go about writing songs these days?

Well, I’ve known Jeff a long time. Sometimes he just comes up with a groove. You know, it's a different world now because we’re dealing and zeros and ones. A musician can send me a track that I might like or not like. But if I happen to like the track I can fool around with it and try to develop a melody, then put a horn on and send it back to him. Everything is time coded, zeros and ones. So Jeff sends me a track, I play trumpet and send it back to him—zeros and ones, sent to his email or dropbox or whatever—and he can just slide it into his setup. So that's just the way we’ve been working for the last year and a half. We’re far apart in trying to be safe, but we've been making music this way. If we can do it in a tasteful way, it feels a bit like you're fooling Mother Nature.

BE: Well, you're fooling the listener. Because when I listen to that song, it really sounds like you're in the same room together having a great time.

That's the way I want it to feel. To me, all of the arts are really about the feel. There's no other component. The feel is that thing that touches you when you hear it, and you can't identify it. That's the beauty. You can’t identify why you like a Louis Armstrong solo, or that Miles solo. You know you like it. And you know that Coltrane is a monster. But what is that element that makes you fall in love with what they do? You can't put your finger on it. This might be a wee bit technical but the perfect example of that was a dear friend of mine, Stan Getz. One of the greatest jazz musicians of all time.

GC: Sure.

Stan and I were close. We were like brothers. I produced a couple of albums for him, and at one point he said, "Can I help you? Can I do something for you?”

I said, "Yeah man. I'd like to learn to play bebop. I didn't play with Coltrane or Charlie Parker any of those great musicians like you guys. I just want to get up to my own water level.”

He said, "Well, what can I do for you?"

"Well, for one thing, do you think I should study the II-V-I changes in every key to begin with?"

BE: That’s the Berklee School of Music way.

Right. That's page one at all music schools. You learn II-V-I changes in all the pop songs and a lot of jazz songs in every key. So I asked him, "Do you think that's the way to start?” And he said to me, [pause] "What's that?" [Laughter]

Amazing. Those old-timers didn't think like that. We've studied them. We've found out what kind of notes they play on a particular type of chord change. But they didn't think that way. That was a big eye-opener for me.

GC: Herb, what I find really interesting is that you get to decide exactly what you want to play. The producer has nothing to do with it. It's you. I've recorded in France a lot. And the producer will say, “If you do this is going to be a big hit.” And you have to try it. But you can say, "No, I want this and that's that."

That's absolutely true… except in the case of my wife, who I adore. We were doing something yesterday. We were recording a song, a beautiful song. She sounds really good. But look, right here, I don't want to condition you on how to do it. I'm just giving you a thought. You might phrase this another way. You know, I am very reluctant to try to impose my musicality on her, because she's very musical and she has her own way. But it's touchy when you're working with another artist.

BE: Especially when it's your wife.

Yeah.

GC: That must be stressful.

Do you know the difference between a terrorist and a female singer? [pause] You can negotiate with the terrorist.

BE: Wow. Don’t let Lani hear that one.

GC: You know, listening to this new CD, you sound so happy to be back doing things. I can feel happiness in it.

That comes naturally to me. The Tijuana Brass had a happy quality to it. I remember one time we were playing in Las Vegas. I was sitting at the blackjack table, and this lady comes up in whispers in my ear, "Your music is so happy in a melancholy way."

GC: That's perfect. Absolutely.

BE: I still hear a bit of that double trumpet sound that goes all the way back to The Lonely Bull.

Yes. Occasionally I use that, but I don't think that's the reason it works. I'm back to what I said before. It's all a feeling. If you hit something that makes you feel good, where you stop your car and you want to know what record that was? That's the goal. That's what I look for. If I record something and I don't feel it, why would I expect someone else to feel it?

BE: I have to ask you about your cover of "America the Beautiful." It's very moving. But what I find so interesting is the rhythmic backing. It's a 6/8 rhythm, which to me sounds African. So we have this very elegant presentation of the national song but in this unusual rhythmic context. How did that come about? It is a unique cover of a powerful song.

Well, I thought the best person to do that song with me is somebody who really doesn't cherish the song as much as I do. So my friend Jochem van der Saag from the Netherlands lives about eight minutes from me. He is a very creative guy. I mentioned that song to him and gave him a little demo. I sent it to him and he came up with this groove. I'm sure his take on it is different than if I'd given it to an American composer or an orchestrator. They would've heard it in a different way. He put it in a different energy and I thought it was beautiful.

BE: To me, it's like this subtle statement of the Black side of America bubbling up in that rhythm. It makes it very poignant for me.

GC: Herb, I'm so happy to be with you today. You can't believe it.

BE: Yes, you’ve got a history.

GC: Every time my show started, [sings “A Taste of Honey”] a hundred and 50 million listeners would hear that for 50 years. Can you believe it?

I'll tell you what's even more striking for me. There’s a song from the Whipped Cream and Other Delights album, which had “A Taste of Honey" on it. One of the TikTok kids picked up the song called “Ladyfinger,” and made a video of it. And that album, Whipped Cream and Other Delights, went to number one on iTunes and on Amazon. Unbelievable.

BE: Because of a TikTok video?

A lot of it was just feeding off that. These kids got into the album 60 years later. I mean that's amazing.

GC: That is. The funny thing is, my show was on the Voice of America, and it was a breakfast show, and people. They said 150 million people a day would listen, because it was going to Africa and around the world. At one point my producer, the head of the department, said, "Georges, ‘A Taste of Honey’ is a little bit old. You have to change it.”

I said, "What you mean I have to change it?”

"Yeah. You have to rejuvenate. You have to do something new."

I said, "I’ll tell you what. I will try to do it, and if people are unhappy, I will go back to my 'Taste of Honey'.” And you know what? It lasted one day.

It is a particularly good cut. I like it. It wears well. It still sounds good. I remember after recording it, when it got on the radio, it was struggling for a while. Well, the whole story was that it was supposed to be the B-side of the record that my partner Jerry Moss wanted to release. “Third Man Theme” was on the A-side and “A Taste of Honey” was on the B-side. When I got my group together, we were playing in Seattle, Washington, at a club there, and every time I played that arrangement, people went crazy. Sometimes I played it twice in a row. There was something about it. So I called Jerry and said, “Jerry, listen. Turn it over. There's a focus group here that's telling me that ‘Taste of Honey’ is the record."

He said, “No. You can't dance to it. It stops in the middle and starts again. Radio is not going to like it."

I said, "Turn it over." Anyway, we did, and it finally was a big hit. So you never know. I don't know what a hit record is. You go by your gut. And A&M, in those early days, there were a lot of little record companies that were just operating out of the trunks of their car. And every now and then somebody would come in with a master and ask if we wanted to distribute it. So this kid came in with this master. I heard it. It was too long. It was out of tune. There was nothing about it that I liked. So I passed on it. I just didn't feel it. I said, "Listen, man. It might be a good record. I just don't get it." Anyway, I turned it down. That record turned out to be "Louie, Louie."

GC: “Louis, Louis.” Yes.

…Which was number one for about eight weeks in a row and every time I heard it, to tell you the truth, I still didn't like it. And I still don't like it today.

BE: Stick to your guns, man.

Well, I try to stick to my gut.

BE: I just heard that this new album debuted at number two on the Billboard Contemporary Jazz list. That must feel good.

Yes. I'm amazed. I'm a lucky guy. I'm grateful. I wake up in the morning excited about what I’m going to do that day. I'm a right-brain guy, a card-carrying introvert. I can entertain myself by painting, sculpting and making music. And I'm fortunate that other people like and appreciate what I do.

GC: You know, Herb, I was just going to ask you about that. Because we’re about the same age. And I'm saying, "How in the world does he do all this?” Putting out a new record, paintings all over the place and museums, something like nine sculptures in Chicago…

BE: Those sculptures are amazing. I've seen them.

GC: And plus, you are going on tour.

That's something we've missed. We had to postpone 50 concerts with my wife last year, and I miss that. It's weird. I don't miss the adulation that I get from folks. I just miss the actual playing with live musicians and creating stuff on the fly. That's what we do, even though we do a Tijuana Brass melody and that will be pretty much the way we play it. But everything else other than that is pretty much open to how it feels on that particular night.

GC: But you still have that energy. That energy, which I really admire.

I think the arts give you energy. I'll give a little something. You know, I have a jazz club here in Los Angeles called Vibrato. And about four years ago, maybe five years ago, Dave Brubeck played there. At the time, Dave Brubeck was 88 years old. He walked up on the stage. I was afraid he was going to fall off the stage. He was kind of schlepping onto the stage. He sat at the piano, and my goodness. He started playing like a kid. He just played and did his thing. He was Dave Brubeck. Boom. When he stopped playing, he schlepped back up to the green room.

I went up to see him, and he was on the couch. He was kind of laid out a bit. And I said, "Man, you are something.” It was like an infusion. And I think that's what music and the arts do for people.

BE: Well, Georges, maybe you need to get back to singing.

GC: I have a story about Manu Dibango. You know him, the Cameroonian sax player who created “Soul Makossa.” I had a B-side that was supposed to be the number one, but this guy flipped the record… and the rest is history.

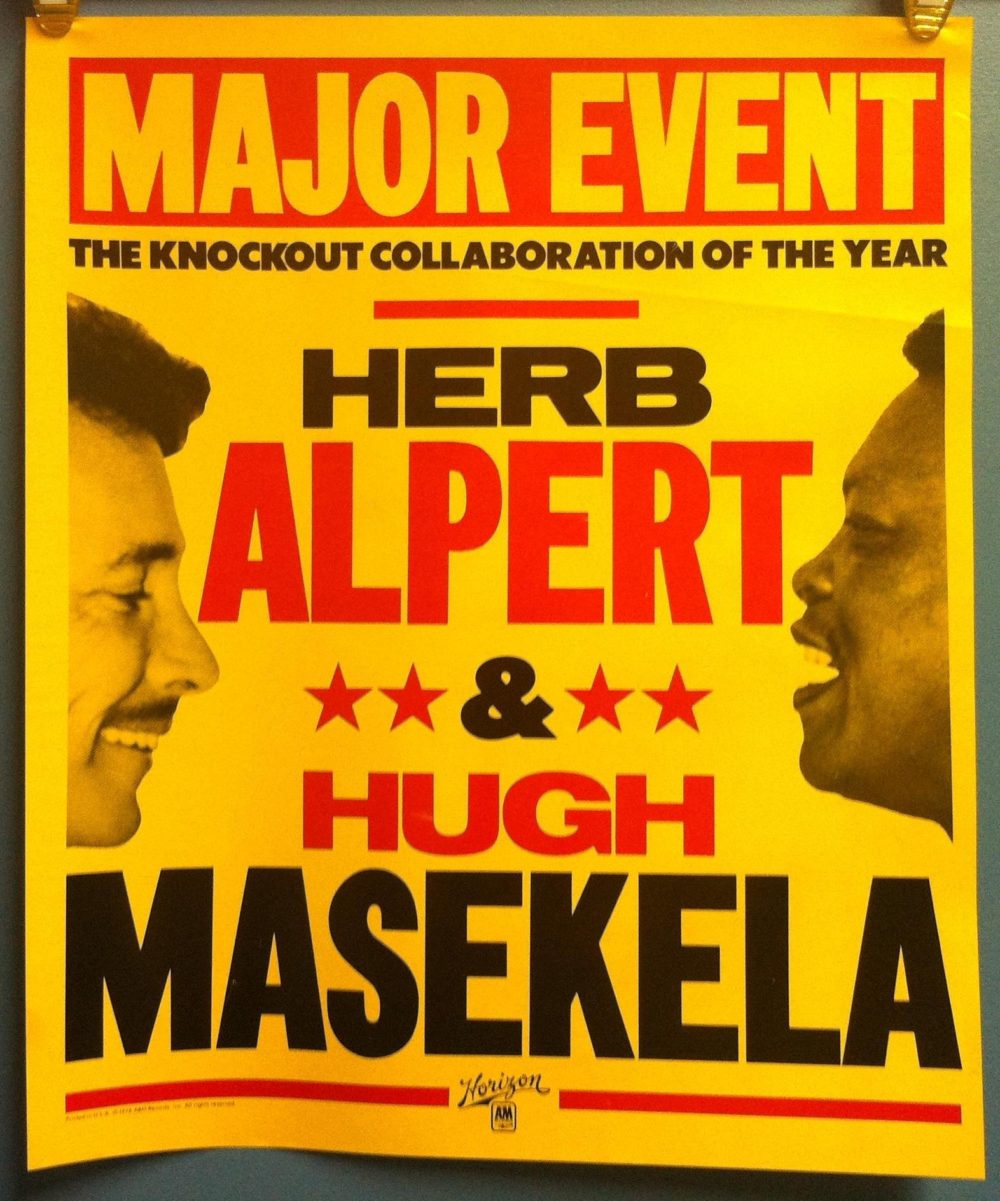

BE: Both of you guys were good friends with Hugh Masekela. I'd love to hear you talk a little bit about Hugh.

I loved Hugh. He was original. He was funny as could be. He was plugged in. He was political, and he had definite thoughts about what should be happening in this world of ours, but he was so much fun to play with. He had this very unique sound. I think we did a couple records that were completely memorable. We did a version of “Skokiaan.” That one is one of my favorites, because it just cooks all the way, really a nice recording. And there was another song called "Moon Goddess,” which is really nice. It was a delight to play with Hugh. He was just fun to be around.

GC: That he was!

We had a mostly African band. Jonas Gwangwa. There was something to listen to. He sounded like a wild elephant. Unfortunately, he passed away a few months back.

BE: I saw that.

GC: Have you played with other African musicians?

That was my only experience. Of course Stewart Levine is a dear friend of mine. Stewart produced the albums with me and Hugh. And Stu did the record "Grazin’ in The Grass” with Hugh.

BE: Right. My first introduction to African music. You know, those two guys were very involved in the Zaire ’74 music festival that happened during the Rumble in the Jungle. When George Foreman got injured and they had to delay the fight, music filled in the gap. Hugh writes about that very memorably in his autobiography.

Yeah. Well, I've been fortunate. I'm very grateful for the life I’ve had and I try to pass it on as best I can to younger musicians. I try to do things I think I should be doing.

GC: So what's the future, Herb? What would you really like to do.

I’d like to stay alive.

BE: That's a good start.

My wife is so concerned that something will happen to me so she tries to keep us safe, safe, safe. But I just want to keep going if I can. I have over 1,000 paintings. My wife lives in fear if something happens to me, what the hell am I going to do with all those paintings?

BE: That would be a hell of a garage sale.

Yeah. You would need a garage and a half.

BE: But you are going back on the road next year, right?

The 2022 concerts are going ahead. But we have an out clause. If it's not safe in that period, I'm not going. But I hope to, because I miss it. I really do miss playing live music.

BE: You said when you make a record you are mostly looking for that vibe. But I wonder: Was there anything on this record that you felt was a response to the strange time we’re living through now? I guess I kind of feel it with your cover of "Smile" at the end. But I'd love to hear how you thought about it.

“Smile” for sure. But I think “Yesterday” has a poignant message. I think a lot of people, including myself, my wife, and my kids were talking about things that used to be happening and that are not happening now. I think “Yesterday” kind of sums up the feeling most of us have. What the hell is going on? We’re getting a little raggedy in terms of us as a human race. I think we need a little ethical revolution.

BE: Herb, you were in your heyday in 1968, which I think of as the only time in my life you could compare with what we’re going through now in terms of national trauma. That was a very different trauma, but it was intense in its own way. The assassinations, the Vietnam war and all that urban unrest…

GC: Well, we’re facing something really more serious now. It might be the end of this world. We’re trying to put together something to get people more aware of the situation, because there’s a feeling that it's business as usual these days. Nobody's really aware of… Jesus, It's the end of the world. The oceans are rising, ice is melting, and all this toxic stuff is coming out of this earth. It's frightening. And yet, “Oh, toujour gai!” Life just goes on.

You're right. The urgency is not there as it should be. We need a person, a leader, an orator, someone who can get up there and give you goosebumps saying the right things. We don't have that.

GC: We were starting to work on this project, myself and a friend of mine. We have about 180 musicians in Europe, and we’re starting to get some here. But unfortunately, my partner died recently. And now I have to go to Youssou N’Dour, get everybody together and see what we can do. And if you don't mind, Herb, I will ask you at one point or another. I will first show you what it is. But it would be great if you can join the chorus. It's called "Together, We Are One.”

BE: Herb, do you ever play D.C., Georges’ neck of the woods?

Yeah, but I can’t remember the venue. My memory is not what it used to be. I think I only remember the things I want to remember.

BE: Speaking of that, I was just writing about the 50th anniversary of George Harrison's album All Things Must Pass. This box set has a lot of the original demos of the songs, with just George playing acoustic guitar, Ringo on drums and Klaus Voormann on bass. It's so beautiful to hear those songs stripped-down like that. Incredibly moving.

George recorded for us when the Beatles broke up. He spent some time here at the house. He was a lovely guy. Unpretentious. Trying to do good things for others. And he married one of our secretaries.

BE: Is that right?

Oh yeah. I can't say enough nice things about him. A really nice person.

BE: Beautiful musician too. Those songs really hold up well. Speaking of A&M, one more question before you go. What did you look for in an artist that you were going to sign? I'm sure it was that gut feeling again, but was there any criteria?

Absolutely. I didn't want to get the beat of the week. I wanted an artist who had their own magical thing to say in their own way. That's why I signed The Carpenters in ‘69. If there is a music I like or I recognize something in the voice... Richard was a student of recording and he was a really good arranger. I took a chance. Most of the artists that we had, like Cat Stevens. He didn’t follow the beat of the week. He was uniquely special. You heard him and a guitar and he could knock you out with his passion. I think it's all about passion. We tried to sign artists that had that magical thing. I'll tell you one more story, then I have to go: Waylon Jennings.

GC: Waylon Jennings. Oh my goodness!

We signed him in 1964. This was when I knew A&M was going to be a big success. I used to fly to Phoenix, Arizona where Waylon was playing. I did this one record with him that was called Four Strong Winds. It's a tune that was written by Bobby Bare. It was a really good recording that I did with him, and Chet Atkins happened to hear that recording.

Chet was the head of RCA in Nashville at the time, and he made some overtures to Waylon, that when he gets out of his contract, he'd like to talk to him. Well, he shouldn't have done that. He was jumping right over our deal. At that time, I wanted to make Waylon a little more pop. But Waylon wanted to be a country artist. He told me and my partner Jerry that he had had this experience with Chet Atkins, and we decided to let him out of his contract so he could go with Chet Atkins. Chet was the god. He was the guy that all the country artists wanted to be with.

I remember the day we signed his release. He had three more years to go on his contract, and we decided to release him, and I looked at Jerry and said, "This guy can a be a big artist." And Jerry said, "Yeah, I know. And we let him go." And I said, "Man, if we can be that honest with our artists and have that much integrity, we’re going to be a big success." I was so happy we did something like that.

BE: That's beautiful. Thanks so much for speaking with us, Herb. Always a pleasure. Send our best to Lani, and thank her for bringing so much Brazil into your sound. We really appreciate that.

GC: And thank you for the great music.

You're welcome. Thank you guys. Be safe. Till next time…

Related Articles