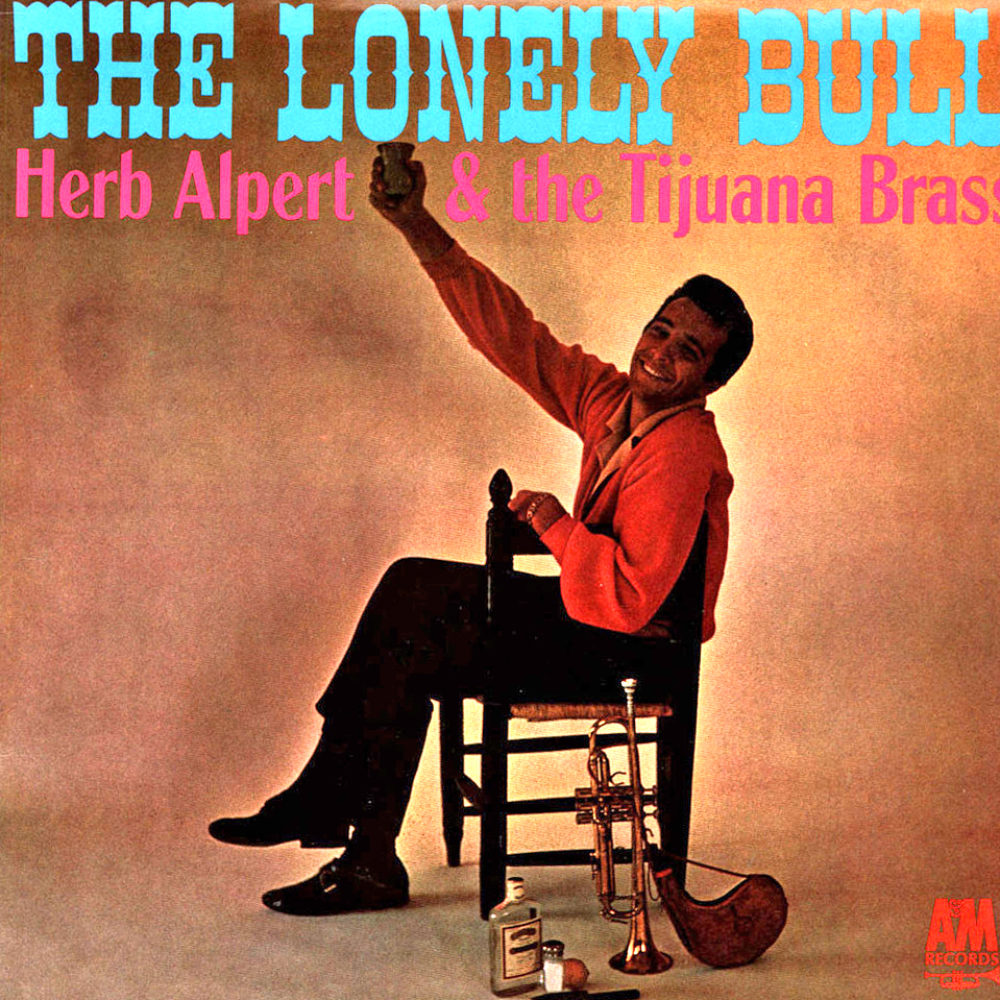

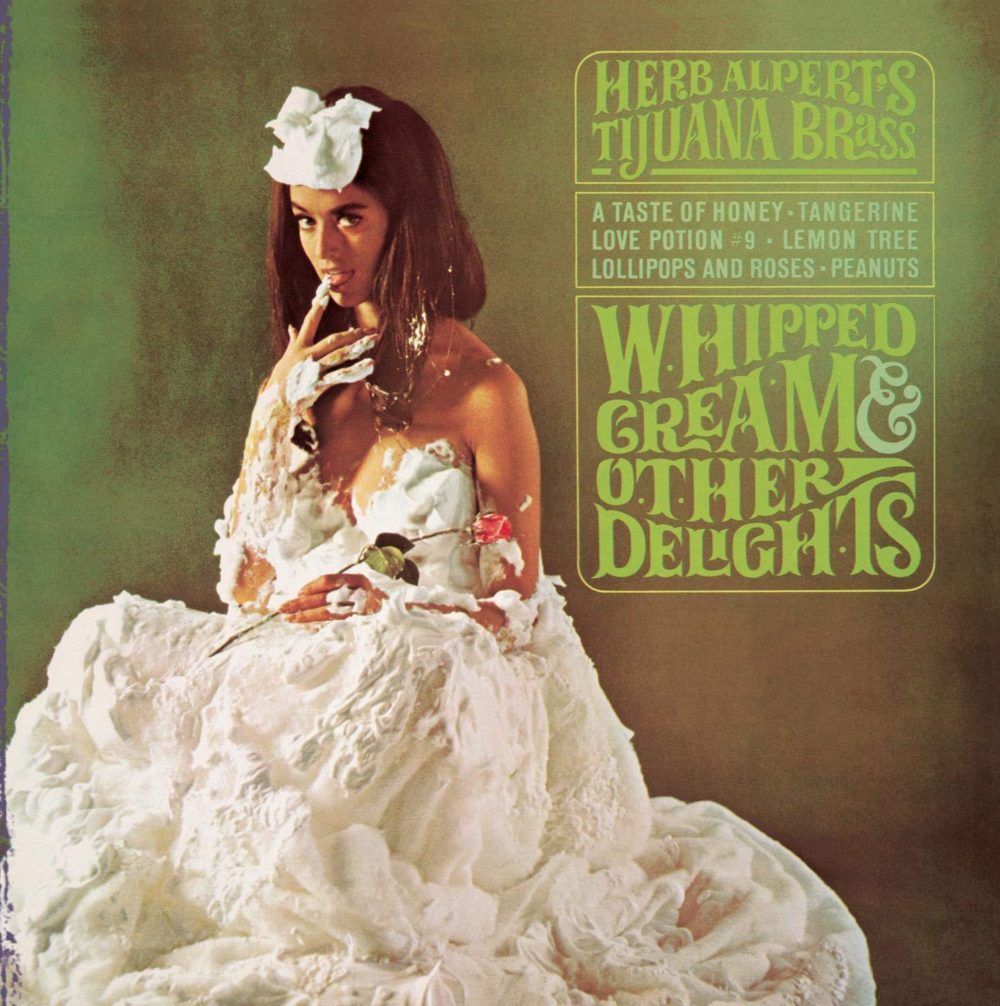

In 1962, when I was seven, my mother bought a copy of Herb Alpert and The Tijuana Brass’s debut album, The Lonely Bull. She dug it because she had spent one of her post-college years in Mexico tracking down folk songs to play on guitar. I dug it too, and gradually became more and more interested, especially when subsequent albums Going Places (1964) and Whipped Cream and Other Delights (1965) came out. In a thoroughly absorbing new documentary Herb Alpert Is…, by John Scheinfeld, we learn that in 1965, Alpert and the band had more Top-40 hits than The Beatles! Even as my musical tastes steadily expanded, I remained an ardent TJB fan until the group disbanded around 1970.

Life went on.

Some 45 years later, I was invited to New York’s ritzy Café Carlyle to see Herb, his wife Lani Hall, and their accompanying trio perform. I had paid little attention to the artist in all those years but I was intrigued. Listening that night, I was reawakened to a sound that had meant so much to me as a kid, and also thoroughly beguiled by Herb’s witty anecdotes and easy way with the band and the audience. In short, I got interested all over again. In subsequent years, I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing Herb, and returning to the Café Carlyle for his annual shows.

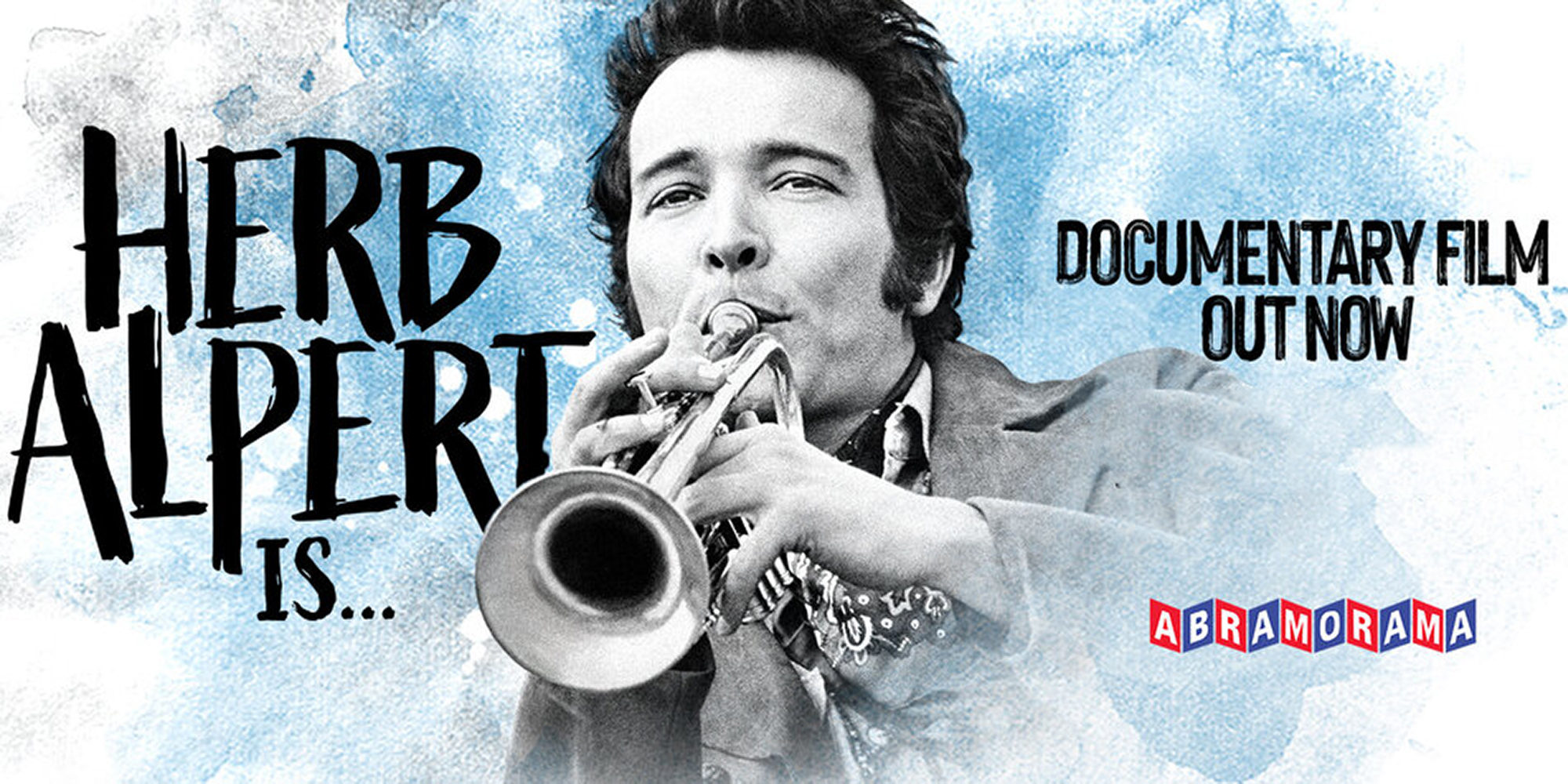

This fall, I watched the online premier of Herb Alpert Is…--truly a superb film biography, and I started checking out the new three-CD box set of the same title. It seemed like time to talk again, so I reached out, and was pleased once more to have a conversation with the trumpeter, composer, record producer, sculptor, painter and philanthropist from his home in Los Angeles. Here’s our conversation.

Herb Alpert: How you doing, man?

Banning Eyre: Very well. Herb Alpert! An honor and a pleasure. Thanks for speaking with me again.

You're welcome.

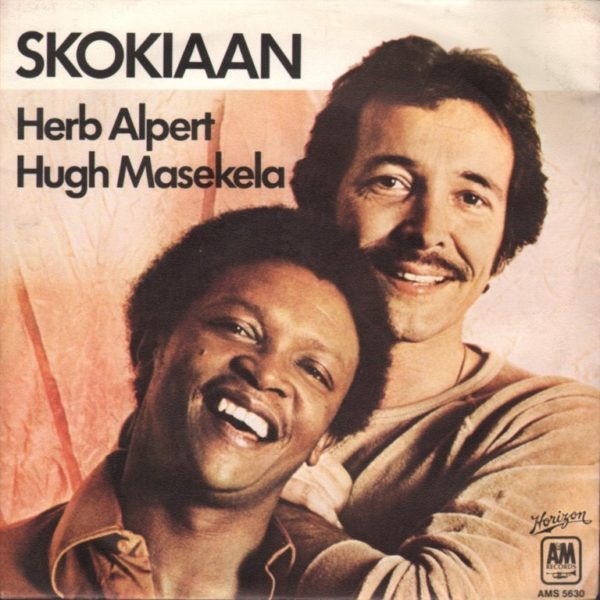

We have spoken in the past. The first time was about music and travel and your Carlyle show. You speak beautifully in the film about a German woman who wrote you a letter saying that she was transported by listening to The Lonely Bull. The second time we talked about your work with Hugh Masekela. And the last time, we talked about the 25th edition of the Herb Alpert Award in the Arts. But today I want to get a little into life and stories.

I enjoyed John Scheinfeld’s film, and I’ve been listening to the box set, which is kind of like rehearsing my entire life. Let me start with a question—musician to musician. I love what you say about finding your voice as a player, and how after a period of imitation and learning from what others have done, you look for that moment when at last you sound like yourself. How do you know when you've arrived at that point?

That's a good question. There's no: Stop, you found it. I think you know that internally. I think you get the feeling. I guess I've told you I tried playing like Louis and Miles. When I heard Clifford Brown for the first time, I felt like putting my horn in a cave. “Holy s%&$. This guy is so far above and beyond.” But I kept going. I guess it was a breakthrough for me when I was listening to a recording of Les Paul where he stacked [doubled with an overdub] his guitar on the recording. I tried doing that with the trumpet, and I hit on the sound that really touched me. It gave me a good feeling. And that was “The Lonely Bull.”

And then that lady's letter to me kind of influenced to me to think that I wanted to make music that says something, that touches people in a whole different way. And by getting all that feedback from that hit record, having opened the door for me to say, "Hey, maybe I do have something that's really special." So it took a while for me to realize that I did have a unique voice.

There's nothing like positive reinforcement, right?

I think it's important. You have to get it either from your parents or friends or somebody. And I did get some of that when I was in high school. I was playing in a little band and I had some people come up to me and say, ""I like the way you play." So that was always a good feeling.

I wonder if that “ah-ha” moment you had with “The Lonely Bull” is a sort of a once-and-done thing, or has there been times over the years when you had to struggle to get it back? Does a player have to persevere to hold onto that originality?

No. I realized I do have my own sound. And Miles Davis substantiated by saying “When you hear three notes you know it's Herb Alpert.” I have my identity, and maybe it's due to the hit records that I had, and people got so used to my sound. So I think I try to do it my way. I've had various experiences as a trumpet player. When I was 18 or 19, I was playing in this big band and my front teeth, four uppers and lowers, they were all loose. I was playing with too much pressure and I felt like if I kept going on that I would lose my teeth. So at that point I said, "I don't want to play that way anymore. I don't want to play high and loud screaming with the trumpet." The instrument was meant originally to be played up to high C and call it a day for the most part. And that's what I try to do with the horn, keep it in that pleasant range, something that would be fun for me to listen to and to play.

I guess what I'm getting at is you have that moment where you find yourself, and for you it's just there and it stays. But there can come further moments like the one you just described where you have further discoveries. That's one thing that really struck me listing through the box set is how much your sound moves with the times. Listen to that first CD, and you are totally in the ’60s.

Oh yeah. For sure. I'm a product of the times. But not anymore. I'm wide open to whatever comes. I'm working with young musicians now and it’s fun. I just try to make music. That's all. I try to make music that touches me. If it's a song that somebody loves and I don't feel that I can play it, I don't. I only play songs that touch me.

Speaking of songs that touch people, I think I've told you before that our longtime host at Afropop Worldwide, Cameroonian broadcaster Georges Collinet, had a Voice of America show back in the ’60s. He was playing American music for Africans, mostly French-speaking Africans. And his theme song for the show was "A Taste of Honey." I love the story you tell in the film about how that wasn't supposed to be the hit. It was the B side. It's a great example of how something that is not expected to be a huge success sometimes turns out to be the bomb.

Yeah, it was a pleasant surprise for me as well. I knew it was a good record. I had reached a point in my career—this might sound a little bold —I remember listening to the whole Whipped Cream and Other Delights album, and “A Taste of Honey” was on that record. I was sitting at my console at Goldstar, the recording studio, listening to the entire album. And I was thinking to myself when I finished, "Man, this is good. This has a good feeling to it." It made me feel good listening to it. So I knew there was something there. For me. I didn't know there was anything there for anybody else. The point I'm trying to make this if you don't feel what you’re doing is good, why should anyone else feel good about listening to it? I think it's an important ingredient to be confident in what you're doing and be passionate about it, as I am, and you see the results of that. But timing also plays a big part in everything. You've got to be in the right place at the right time. If we tried to start A&M Records in today's environment, we wouldn't stand a chance. If you tried to put a record like The Lonely Bull in today's market, forget it. It wouldn't even get airplay.

Although I have met artists who are very surprised by the songs that the public picks, the songs that become hits. Sometimes they think their best work is getting overlooked, and the songs that they just tossed off with barely a thought become the big hits. There's no accounting for taste, ultimately. But you're right. If you don't believe in it and love it in the first place, it probably doesn't have much of a chance.

Well, I’ll give you a story that's really interesting. Because you know that I worked with Sam Cooke in the early days.

So beautiful. I didn't know that until I saw the film.

Well, Sam and I and Lou Adler wrote “Wonderful World.” "Don't know much about history…" O.K., so Sam didn't know whether that song was good enough to release, so he wanted to do a demo of it, just to make sure that he liked it and he was going to take it to the next level. See he made this demo at Keen Records, and he just had kind of a pickup group, not real heavyweights. Maybe the guitar player was a guy who played on most of his songs, but the rest were just pickup musicians. It was done as a demo. Keen Records put it on the shelf because Sam didn't want it released, so it stayed in their archives.

And then when Sam left Keen Records and started recording for RCA Victor, he had a string of hits. Keen looked at what they had left of Sam's, and the only thing they had was this song “Wonderful World,” which was done as a demo. Well, they put that out because of Sam's success with RCA, and not only did it become a big hit, it was the biggest single record Sam ever had. So the point is, nobody knows what a hit record sounds like.

And I had that experience with A&M when we were really successful and artists used to come in and play master recordings for us. It was all producers who didn't have a record company, but they just had this one record and were looking for distribution. This guy came in with a song and I listened to it and I didn't like it at all. I thought it was too long. I thought it was out of tune. I couldn't understand the lyrics. I didn't get it. So anyway I passed on it. Wished the guy well. And that song became "Louie Louie." Which was number one for about eight weeks in a row.

That makes the point nicely.

Well, the point I'm trying to make… I still didn't like that song when I heard it.

It's not my favorite either, although the Toots and the Maytals version is pretty cool.

I made a gut decision and stuck with it. But I couldn't spot a hit record. I didn't think that was going to be a hit record.

But "Wonderful World"? I can’t imagine not believing in that one. It's such a great song.

Well, it is when you hear it over and over again. And the lyrics are seductive. It certainly has a thing about it. Sam was magic anyways.

What an amazing singer. I noticed going through the box set that in 1968, “This Guy’s in Love With You” and Hugh Masekela’s “Grazing in the Grass” were both on the hit parade at the same time. O.K., I was 12 years old then, but I was very focused on the hit parade. And of course, top 40 radio was very different in those days, such a mix of styles. But I clearly remember loving both of those songs, and when I look back on that moment, you were still my number one musical hero, but the world was opening up. I was moving into rock ’n' roll and blues. A lot of things were happening that year. We spoke about Hugh in an earlier interview, but there’s one question I didn't ask. How did it start? What is your first memory of knowing about or meeting Hugh?

Well, I was friends with Stuart Levine, who worked on a lot of Hugh’s records. They came to the office one day and we started talking. I took an immediate liking to Hugh. You could see he was a real musician. He had something, an original sound and an original concept. And when he heard my music, he said, a lot of the things that I do instinctively reminded him of music they were making in South Africa. So one thing led to another. We said, why don’t we try making a record together? So we did that first album, and there's some really great stuff on that first album. I have a lot of good memories of playing with him. He did not B.S. through the horn. He would always just pick up the horn and play. He would play something two or three times and it would always be different, always be unique, always have a Hugh Masekela stamp on it.

Hugh was another of those “three note” guys.

So then we decided to do a little traveling in the United States. We had a wonderful band that he put together. In fact there's a song that I just re-recorded that was on that live album that we did called "Shame the Devil."

I love that album. In the booklet for the boxed set, there’s a Robert Palmer review of one of your shows with Hugh. It's not particularly kind to you, and he doesn't seem to know a whole lot about the background of South African jazz. But I like his reference to old Haitian and Cuban dance bands. I wonder what you think of that review and why you included it in the box set?

Oh, I didn't even know it was there.

Oh really?

My nephew, who is also our manager, Randy "Badazz" Alpert put that together. I don't read those things. I don’t read the reviews. Some people love me. Some people don't. It's not important to me.

I understand. It's probably because Bob Palmer is such an iconic music writer that your nephew decided to include it. In any case, it's an interesting time capsule. But let me ask you about one of the songs you did with Hugh, “Skokiaan.” How much do you know about the back story of that song? Because it’s got quite a history.

No, I really don't know the history of it.

It's a little bit like Pete Seeger and the Weavers with “Wimoweh.” Pete scored a big hit with it, as did others, and then there was this big battle to get credit to the guy who actually wrote it, Solomon Linda. And he did eventually get his due. “Skokiaan” was written by a Zimbabwean composer named August Musarurwa. When I was living in Zimbabwe, I got to know a woman who made a film about the composer and that song. He is now recognized as the composer, but it's one of those funny stories: an obscure African musician writes a song, and I guess Louis Armstrong was the first guy to record it, and then it just goes. And then everybody's playing it.

It's got such an uplifting melody to it. That version that Hugh and I did is one of my favorites that I've ever recorded. It's just got a real driving, honest, fun feeling to listen to.

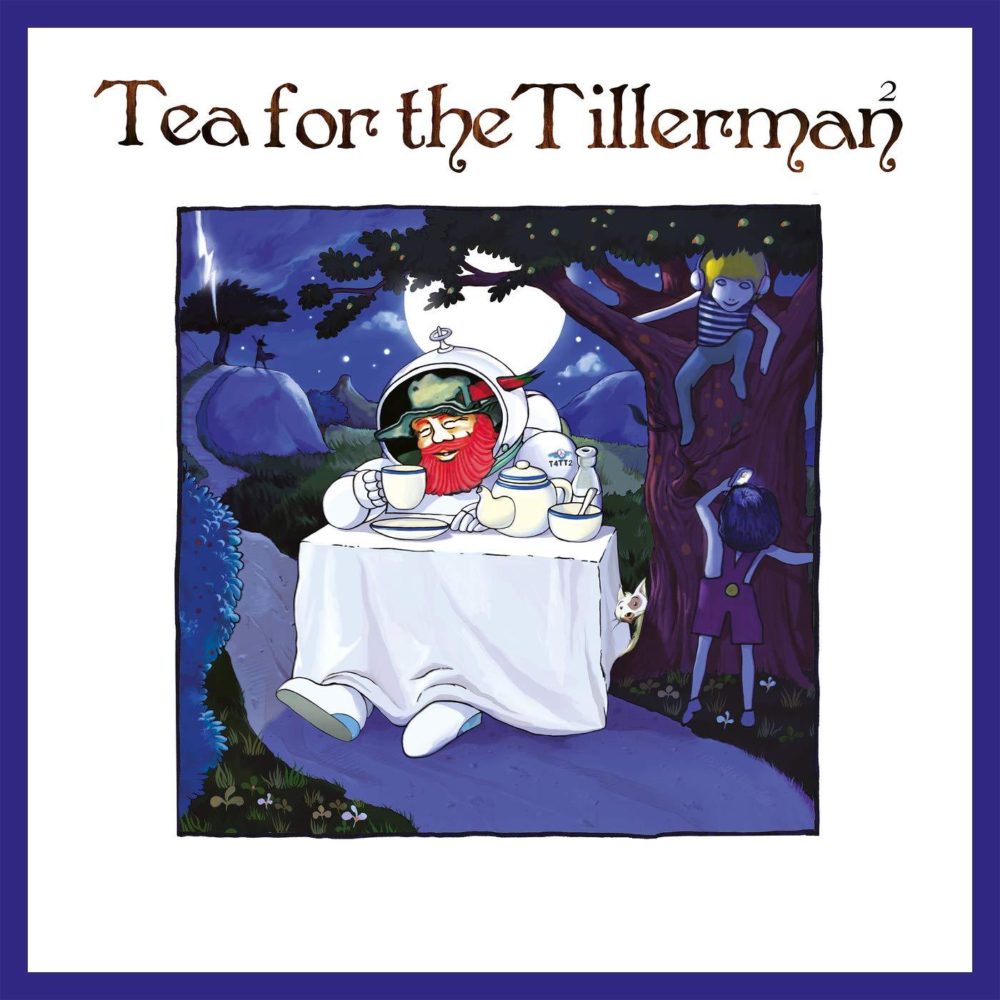

Absolutely. I'm so glad you included that in the box set. I have a question about the A&M years. I'm guessing you're aware that Cat Stevens recorded a new version of Tea for the Tillerman. He redid all those songs with new arrangements and some new lyrics. Have you heard it?

I've heard bits and pieces of it.

It's very interesting. I'm wondering what was behind your choice to put him on the label in the first place.

Oh, man, I think this guy was an amazing artist. He fit right into the category. We weren’t looking for the beat of the week with A&M. We were always looking for the artists that had that original thing, that was theirs, that was not necessarily majorly commercial but that had something special. Cat was one of those guys, even just Cat playing a guitar. I remember he was playing at the Troubadour here in Los Angeles just by himself. It just knocked me totally for a loop. The guy was so passionate. He had these original songs. He had the groove in his body. I just thought he was special. In fact he wrote a song for me called "Whistle Song," while he was traveling in Brazil. He came back with this one song and he gave it to me. So I really admired him as an artist. One of the great ones.

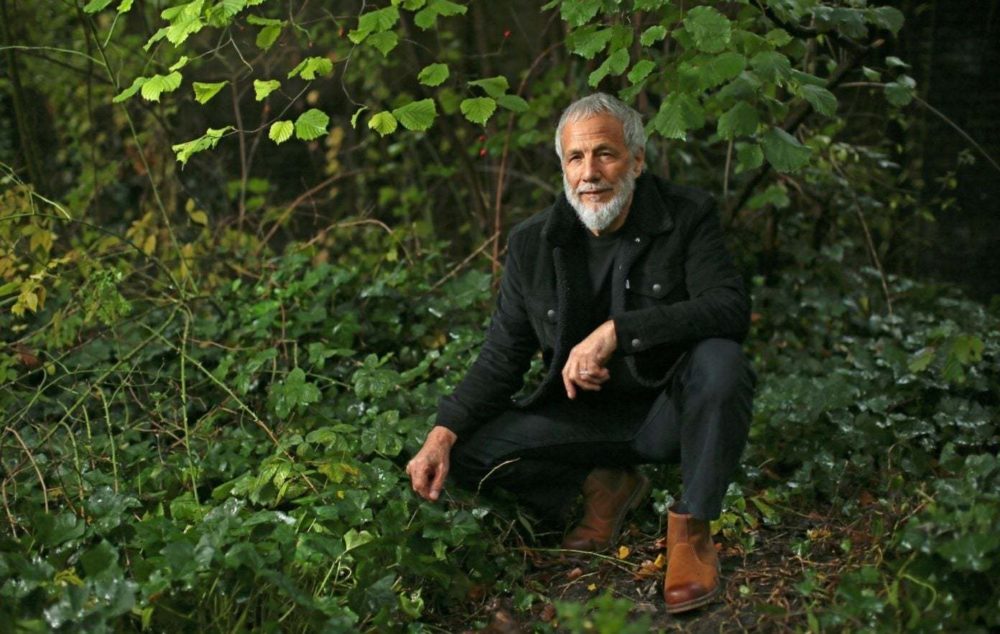

I was a fan too. And then he kind of disappeared for quite a while. I saw him perform about 10 years ago at a festival in Morocco, and it just sent chills down my spine. It was so great to see him up on the stage again.

Well, you know, the guy is completely committed and passionate about what he does. And you feel that immediately.

Tremendous composer and singer too. Do you have any memories of the session?

No, that was recorded in the U.K. That's how it got to us. Through… Oy vey, I can't remember the guy’s name, the guy who had his record company then…

No problem. Here’s a question about singing. Obviously you had this enduring iconic hit with “This Guy..” but there have been very few other times when you sing on your records. I can relate to that, because I used to be a singer-songwriter, but I didn't think I was much good at singing, so now I just play guitar.

[Laughs] That's the confidence you don't need!

So I thought that maybe you and I share a kind of exciting but tenuous relationship with the art of singing. But I wonder how you feel about it now. Do you enjoy singing? Do you do it informally?

No. I was just doing that because we were doing a TV show and the director asked me if I could sing a song. And I had a friend by the name of Burt Bacharach…

Yeah. Heard of him…

... And I just said, "Burt, is there a song you think I can handle? Maybe a song you find yourself whistling in the shower, or you didn’t get the right recording…”. Anyway, he sent "This Girl’s in Love With You." I thought I could handle that melody and I liked the lyric, although the gender needed to be changed. And that's how that came about. It was on the TV special that we did with Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass. And two weeks after that record was released, because of the exposure on the TV show, it was number one in the country. It was an amazing whirlwind experience. I had no idea it was that good.

But it's interesting to me that even though it was such a huge success, you did not continue that direction, singing, I mean. And I'm wondering why?

Well, I don't think of myself as a singer. I've been playing trumpet since I was eight years old, and this is what I do, this is what I love to do. [Blares out a lively riff of lip-trumpet]. I've been able to do this for so many years because I love it. I'm not a singer.

O.K. One question about the Harlem School of the Arts. It’s quite a story about how you got involved 10 years ago. I understand you’ve just finished a renovation project at the school. But of course, like everyone else, they're having to do virtual teaching now. I'm just curious to know how the school is managing the strange reality of the pandemic.

Well, it's been a tough slog. We finished the renovation, and were not able to fill the space with students. But there's virtual learning with the students, and it's going to be great as soon as this pandemic leaves so we can feel confident with crowds again. I am just completely proud of everything that's happened to the Harlem School since we stepped in in 2010. I saw this article that they were closing and I couldn't believe it. That didn't make any sense. A school centered in the middle of Harlem which has given us so much art in the last hundred years. Folks on the East Coast didn't have the sense to be able to keep this thing floating, so I jumped in. And I'm glad I did. It's been a joy that I've been able to help put this back together properly and it's been flourishing. And now it's absolute beautiful the way it looks. As we were refurbishing the place, I brought an acoustician who helped with the sound and the look of the place, and it's just as good as it was intended to be.

I love the part of the film where you're visiting classes there. It got me thinking that Afropop may have something to offer the school. We have this 30 year experience of exploring Black global music, and now we’re looking at using our archive in educational ways. It might be interesting for those students to get a more global outlook on where Black music came from, how it's affected the world.

Mmm. Good.

Just one more. As I mentioned earlier, listening through the set, it really struck me how you move with the times. On the first CD, I knew every note. The second CD much less, because that was the time when I was off in my travels and not paying much attention to American music. And then the third one had a lot of stuff that I related to, partly because I've been lucky to attend some of your shows at the Café Carlyle. But it also really struck me the way the whole feeling of your music has moved with the times.

So I guess my question is, what does the guy who's done everything do next? Is there anything about this unusual time that were living through right now that might affect your artistic choices?

Oh, definitely. I just painted two pieces called COVID 19. I think we all kind of respond to the times. [Pauses] Actually… Well, here's a story. I'd be doing the same thing two years ago that I'm doing now. I paint, I sculpt, and I make music. I've been recording. I have about 20 new songs that I just recorded. As you know, I am an introvert, so I spend my days doing what I love to do. Sometimes I feel that that's not what everyone wants to hear. People are struggling out there, and I recognize that, and I try to do my part whatever I can to help others, but for me, it's business as usual with what I'm doing.

I don't know what my point of telling you this is. I guess I feel a little guilty. I'm just involved in my everyday activities the same way I would be two years ago.

Well, you have nothing to feel guilty about. And I know what you mean about liking to stay home working on things you love. That's one thing I have appreciated about this year. And I guess I feel the guilty too. But hey, we all do what we can.

Absolutely. What instrument do you play?

Guitar.

Did you know Jonas Gwangwa in Hugh’s band?

Yes. Well, not personally, but I certainly knew his music. The trombone player.

He was in our group. I love the guy. He sounded like a wild elephant.

Well, I started with folk and blues finger-picking. Then I got into classical and flamenco. Then I went to Berklee in Boston and studied jazz. But somewhere in the ’80s, I started hearing these African guitar players, and that just took over. I went through my own thing of learning traditional songs and styles, because they have all these unusual ways of playing guitar in Africa and I was fascinated by that. But then I had the same kind of struggle with “how do I find my own voice in all this?” I wrestled with that a lot, but now I think I've arrived at a personal mesh of sounds that does feel like me.

Sound plays a big part in it too. Wes Montgomery recorded for us. I was doing this television show one time. I was the MC, moderator of the show, and I was waiting for him to come in because I had not met him before. And I was thinking, "How does he get that sound? Such a beautiful sound." And his history, he didn't know what a C chord was. He was just playing by instinct. So Wes comes in with his little Fender amplifier, a small baby amplifier with cobwebs in the back of it. He plugs in, and bang, there's that sound. It was just there. It was Wes.

That was the one thing that this trumpet teacher I had gave me. I was having a major problem playing the horn. I was going through a divorce. And I asked him, "Man, should I change my trumpet? Use a different valve oil?" And he said, "No, man. Let me tell you something. It's not about the instrument. You’re the instrument.”

“Mmm. really?"

He said, "Yeah, the trumpet is just a megaphone. It just amplifies your sound. The sound has to come from within."

I hear that. Wes had that incredible way of playing octaves with such a light touch. He was so fleet with those octaves.

But it had nothing to do with his equipment.

Exactly. It was him. Well, I've met so many guitarists in Africa who get incredible sounds out of the worst possible equipment. And you give them a really fancy guitar or amp, and O.K., the sound quality is better. But the essence is the same. And you realize: it's him. It's his technique, his touch, his feeling.

You asked me, how do you find your own voice? Well, you see, if you can put your voice through the instrument, then you found it.

And you certainly have, in so many ways. It's an honor to speak with you, and please send our best to Lani. It was such a pleasure to meet you guys at the Carlyle.

Well, we miss playing at the Carlyle. I like that place. They always treated us well. It's a different audience than when we play on the West Coast. When we play the West Coast, people come in their $4,000 torn jeans. But where you are, people are dressed like regular people.

And you have distinguished guests like Bill Moyer and Jimmy Fallon showing up.

Oh yes. Robert Redford was there one night. And the manager told me right before we went on. And I said, “Well, do me a favor, do not tell Lani he’s here.” It was a beautiful night.

O.K., man, enjoyed speaking with you. We'll do it again some time.

Thank you so much.

Be safe.

Related Audio Programs