Over the years, there have been several documentary films focusing on the session and touring musicians you've heard but never really knew, such as The Wrecking Crew (2008) about the group of Los Angeles session musicians who worked throughout the 1960s, Standing in the Shadows of Motown (2002) about the Motown session musicians, and Immediate Family (2022) about the 1970s Los Angeles session and touring musicians. All these films turn the spotlight on the artists behind the stars. African music has also had its session and touring musicians who have contributed enormously but have also mostly remained unknown.

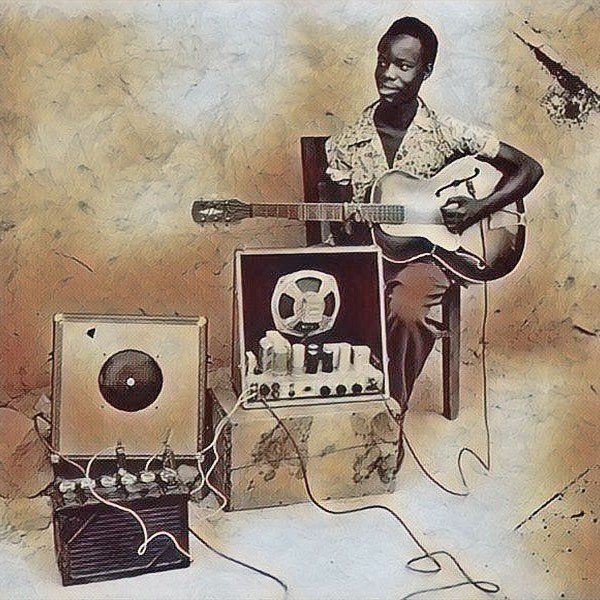

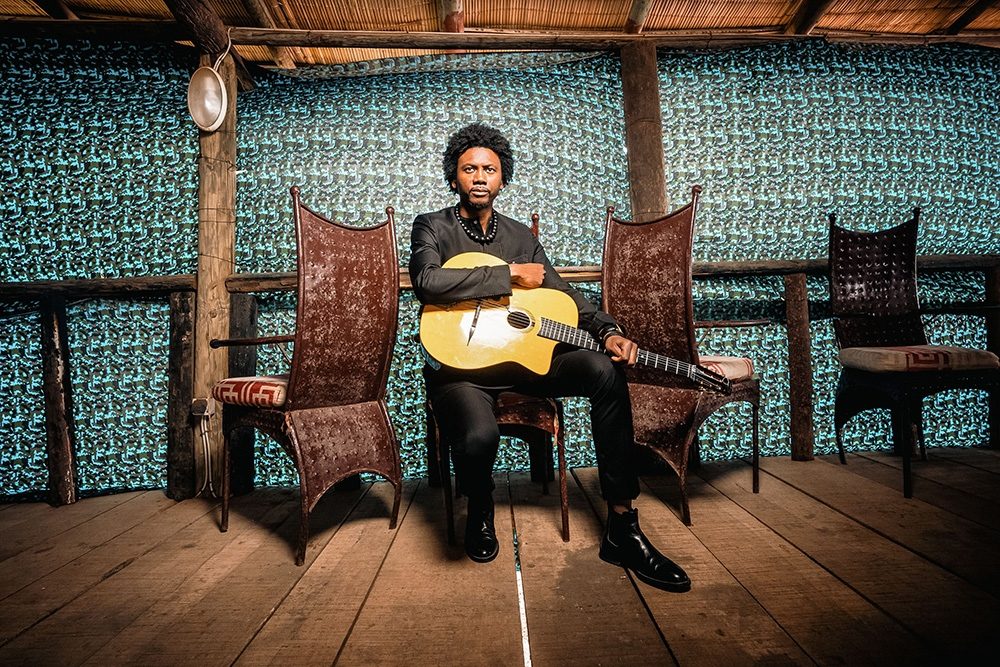

Hervé Samb is one of these musicians. A mostly self-taught artist from Senegal, he began learning guitar at the age of nine and two years later this prodigy was touring the country in a band. Today, at 46, he has played, toured, and recorded not only with African musicians, but also jazz, blues, and world music artists around the globe. Without a doubt, if you have seen or listened to some of the many renowned artists of the African diaspora, you have very probably heard his guitar. According to his biography, he has contributed to over 100 albums to date, both as musician and composer. In addition, he has released a half dozen solo albums, as well as two albums of collaborative projects: one with Belgian guitarist Pierre Van Dormael, the other with Colombian-American percussionist Daniel Moreno.

We caught Samb's showcase back in April at the Jazzahead Trade Fair & Festival in Bremen, Germany. Not long after, we did a Zoom meeting where we dove into his fascinating history, important collaborations, and his own recordings. We first spoke about his early years and his later collaborations with musicians he has been fortunate to work with. We'll have a second article out soon where Samb discusses his own music and recordings.

We won't spend more time giving you a biography in this introduction, but rather will let Samb surprise you with his story. We found him to be a very humble and generous person, who definitely still feels blessed by all the amazing opportunities he has been gifted with in his life. You can find information on other many collaborations we didn’t get to mention on his website. The following was edited for both clarity and length.

Banner image ©-Guillaume-Saix

Ron Deutsch: What a great show you put on at Jazzahead.

Hervé Samb: It was really good for me too. Thank you so much. Thank you. Thank you.

I'd like to start from the beginning. I read that you were performing on television in Dakar when you were just 11.

Yeah. I was very lucky as an African in Senegal to have parents – that are not griots – that actually accepted the fact that I wanted to be musician and were pushing me. They were very open-minded. There used to be places where they used to hire musicians and bands to play at a club, like Youssou N'Dour and Orchestra Baobab would play at such a club. So some people of the press found out that I was playing guitar at this place, and it was something very novel. I would say I was one of the few young boys being able to play with a band, and we were touring all over the country.

And this was at 10 years old?

Well, I started with the music at nine and then started making gigs at ten. [LAUGHS] They would take from school and then go on stage.

And actually I was lucky because I met this French guy who had come to, you know, discover Africa, and he really put me onto the blues at the age of nine. I was just so passionate about this instrument. Then I discovered B.B. King and then Jimi Hendrix. So quite, quite fast, I started to play blues, and that was something very novel for a young Senegalese.

So there was this one TV show on Saturday afternoons – and this was at a time when there were not many TV channels. So that show made me famous all over the country because they discovered this young boy playing blues. That's how it happened.

And I wanted to play solos before I could play chords. I figured out how a pentatonic scale works, and once I figured it out I could play anything I wanted.

But where were you hearing and finding this stuff? This is pre-internet.

I was running all over to find information, like crazy. Like every day after school, I had like four or five guys that were giving me cassettes. I was going to the market buying a lot of blank cassettes. And every weekend, I was running from house to house. And there was this one guy, he was an amazing guy, and he had like 20,000 cassettes in his place. And he played music on one of the few jazz radio stations we had in the country. I was going to his place – and I didn't know who was who – but I was copying cassettes. And this guy was from France, and he would play and show me a couple of tricks. And that was it. He was calling me “B.B. King” at that time already, because I loved it.

So then, put together with the band, we were playing all over the country. It was amazing. We were doing these gigs sponsored by this cigarette brand, Nelson, that was like a young talent competition. So they'd bring a big stage on this bus, and I think we were like 30 or 50 young bands. So the deal was, you come and you do the tour with us all over the country, and then at the end, we came in second. We didn't get any money, but our prize was to make a recording and a video. So that's what got us on the TV. And so it created a lot of excitement, and my parents were very proud, of course, and then they pushed me to do this as a career.

So at this point, you're still a child but really into music in this big way. Did you have any idea that this was what you were going to do for the rest of your life?

I don't know. It as just like, “This is what I want to do and what I'm going to do.” It was something super clear in my mind. I was very lucky to know what I want. I was still going to school, but everybody knew I was going to be a musician.

But as you mentioned, not being a griot, was there some resistance from people because of that?

Yeah, because at that time, music was reserved for griots. At that time, when you did music, you basically served the king, you served the people. It's a different approach. Like here in the West, the musicians they're on the stage, you go to concerts. But in our society, for musicians, it's like, “Oh, come and entertain me.” There's no stage, even sometimes the music is a lower stage and the public are on the upper stage. It's a different approach, a different dynamic. Both are great, actually. It's great to serve and it's also great to take your art and give it the value that the arts should have. But at that time, every parent, they wanted their kids to study and have a regular, respectable job, you know what I mean? So it's very rare to have parents who actually accept being a musician. I wasn't the only one, but I was the luckiest one because I had parents who were supporting me. But there were some others that were super talented, but they never had the support of the family.

Things are different now. You see, I was in the middle class and they want you to be doctor. But then also, most of the musicians at that time who had access to modern instruments were part of the middle class, because they could afford it.

I was going through your catalog, which is enormous, listening and there's the album of duets that you did with Belgian guitarist [and brother of film director Jaco Van Dormeal] Pierre Van Dormael in 2008. It's really beautiful, especially “Skylark.” I love that song. He was very important to you early on. How did he come into your life?

This is an amazing story. The San Louis Jazz Festival was basically the beginning of pretty much everything for me with jazz. When I started to do these TV things, everybody was now familiar with me. So the guy who created that festival was also the director of the French Institute that was based in San Louis – his name was Hervé too. So he had heard about me, contacted me, and said, “Hey, man, you should come and play in the Off Festival.” So I came with my parents, of course. And then, because I loved to jam, I was at all these little clubs during the festival. And this guy, the creator and programmer of the festival came to me and said, “I know exactly who you need to meet. There's a genius that just came to live here in Senegal and you have to meet him. He's a master from Belgium.” So he's the one who introduced me to Pierre.

And then I met Pierre and it so happened he was living just 15 minutes from my house, which is like incredible in Dakar. So every weekend I was at this apartment. Every weekend for three years. But he was more than a teacher; he was like a mentor. And I was basically his shadow. So here I was a young boy, 14 years old, and everybody is telling me how good I was playing, then I saw this real master player guitar. I was completely blown away. And I was like, “How can I get to this level?”

So I asked to take a lesson and Pierre said, “I won't give you any lessons, but I will answer all your questions.... But I won't teach you.” He was a very smart person, because he wanted me to come to the information, you know? He said, “I do not want to change the way you was playing already.” He just wanted to add some stuff, you know? He's passed away now. Pierre was one of the first Europeans who had been to Berkelee School of Music, so it was like I had my own Berklee, here at home. He taught me classical music, bebop, hard bop, avant-garde stuff. So every weekend I was given a couple of standards or classical pieces to learn. He wasn't there all the time, but he'd come back and forth, stay for a while, and then go back to Europe.

But what was he doing in Senegal?

Okay, so he wanted to learn, to understand African music. And he was writing a book about how African music works, why does it work, and also he was teaching. But later, Pierre told me that, “I was there for three years, but the guy who really learned from me was you.” [LAUGHS] I mean, when I came to Europe, I knew more than 200 jazz standards. I was ready to play, I was ready to work.

Yeah, I mean, this guy is gonna be in my heart for all my life because everything he gave me has no price. And then, he taught me how to teach myself, how to be independent. That's why I never really needed to go to school after that. When I came to Europe, I always knew how to get the information.

So now every year I was playing in this San Luis Festival and doing jam sessions with all the musicians coming to the festival because I knew most of the standards they were playing. But they were so amazed about the level that I had in Africa. I mean guys like Richard Bona. He was giving me some advice that I should learn this and that. I was like their little brother because they were so proud to see me play and know already so much stuff. And then I was meeting all these musicians

coming from Paris, the list is very, very long and we were jamming all night until nine in the morning.

And so when I turned 19, I went to Paris. I think Paris was the best place for me at that time because I could play so many different styles of music. I could play jazz and blues, but here's the thing. It was when I got to Paris that I started to learn African music – and when I say African, I mean Ivory Coast, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Mali, Algeria, Morocco. And believe it or not, it's another French guy who put me to African music somehow. Jean-Philippe Rykiel. He's a blind pianist and plays piano but kind of makes it sound somewhat like a kora or balafon on the piano. And I was like, “Wow, this is very interesting,” because he also has this big background of classical music. So he would mix some of those West African lines and add some classical stuff, sometimes jazz, but more classical. He produced a couple of albums with Youssou N'Dour and worked with a lot of African bands. And I thought his music was super beautiful and so he inspired me.

So you're now in Paris. Was your goal to start your own band or to get jobs as a touring musician?

I actually just wanted to take in information, just wanted to grab the information. I would take this job or that job, playing blues or African. I was playing with almost 27 bands. All types of situations – small cafes, weddings, festivals. I was doing everything. I mean, it was just Paris. And people were just calling me here and there, you know. So I did that. And then after a while I started to learn a lot of stuff.

And you wound up playing a lot of American blues in Paris?

Yeah, because of a guy who came from Chicago, Boney Fields. He used to play with Lucky Peterson. I met him because me and Lucky played when I was 14 years old. I had the privilege to jam with him when he played at the San Louis Jazz Festival. I think it was in 1993. They told him, “Hey, Lucky. There's a young boy who sounds like you here. You should call him.” And he was like, “What? Here in Africa? No way.” And he called me up and he was completely amazed. And Boney Fields was the trumpet player in his band at that time. And then I'm in Paris and Boney recognized me and said, “Hey, I have a project for you. We should play together.” And then I get into that blue scene. I played in this blues band for 14 years.

And around two or three years I'm in Paris, I got my first touring gig.... with Amadou & Mariam. So that was my first world tour. I got a call from [Malian musician/producer] Cheick Tidiane Seick asking if I knew who they were and I said I didn't. He said they were looking for a guitarist and pushed me that I should try out for it. But I was late and the last guy coming in. I really didn't know what to expect. They were about to wrap up, and then Amadou said, “Oh, let's try this song.” So I played one, two, then three songs with him, and he was smiling. He said, "Yeah, I think this is the right boy we need.” And like one week after, they sent me on the tour. So all of a sudden I have like 50 gigs all over the world. And that's how I started touring. And I was just 21.

What was it like working and touring with Amadou & Mariam?

Oh, it was, it was great. I mean, Amadou was very happy because I could learn very quickly what he was playing. He couldn't get that with other guys because most of the guys don't get the African approach. So Amadou & Mariam used to love me a lot. But I think the best thing that was very interesting, as I did my first U.S. tour with them, was that I was also going jamming in every city. You know, we were driving four or five hours, then do a show, and right after the show I was hanging with musicians, go in the city and jam all night. So I met a lot of musicians around the U.S..

Then after that tour, I went back to Chicago because I met some musicians. And that's where I discovered the real blues guys playing, and would hang with them. And I discovered some amazing jazz musicians. I was jamming with Von Freeman, the father of Chico Freeman. He used to do a jam session every Thursday in a place named Apartment Lounge in Chicago. And before the jam session, he was lecturing and the crowd would be full of all the greatest players in Chicago, because they knew who he was and showed him a lot of respect. So then I played the first time and after I went to sit down at the bar and suddenly he's talking to me. And he said “You sounded great up there. Keep playing.” And just that line changed my life. Because in Paris, when you're African, they only call you for African gigs. And if the jazz guys call you, it's because they need someone to give some African groove. And I'm like, “Why can't you just call me because I'm just a musician?” And this went on until I came to believe that I might never be a jazz musician, maybe I would just played African. But when Von Freeman said that to me, it was basically like he blessed me. He opened my mind that I was on the right path. So that's the beauty of going on this tour at the beginning. It was the energy, it was just coming together, and that was great.

Would you say you brought some of this musical diversity to Amadou & Mariam's sound because of your background in different styles?

Yes, yes, definitely. Actually, Amadou kind of showed me what he wanted. They needed a second guitar to help him, because he was singing. So he was showing me what he was playing, but then I was adding some stuff because I have a big culture I was drawing from. I remember after I quit the band a couple of years later, I went to Mali and wanted to visit them. So I get there and actually they were teaching and using the show we did in Cologne, and they said to me: “We're trying to teach your part to this guy right here.” [LAUGHS] You know, when you go to Mali, there's a lot of guitar players. But I bring some different stuff, you know.

And then you toured with Oumou Sangaré?

Yes, I did a couple of tours with her, a big one in Mexico. We played all over Mexico and then some dates in Europe. And to me, she's like a big sister. I would say the power of Oumou is the spirituality that comes from her voice. There are a lot of younger singers who sing and have beautiful voices – and almost sing like her – but when Oumou starts singing, there is a strong spiritual connection that she brings with her. I don't know where that comes from, but I noticed that because I've played with many different Malian singers. She's been in the business for a long, long time and she's still quite young. Also, what is very impressive is that also it gives her a sense of open-mindedness. She's not only traditional, she's completely open, and she really respects musicians. One thing I remember was she never wanted to do an encore. Like when the band finished and the people are crazy and they want us to come back. And she'd said, "No, I'm tired." And we were like always pushing her: “C'mon girl, let's go!" But she's cool. It was a long tour though, so I understood, but you know.... [LAUGHS]

And what did you learn from playing with her?

You know, with her it's always this wassoulou style of music. Wassoulou is this Malian style and is , actually really close to blues, like Ali Farka Touré. So it's that approach that is quite strong in her style. It's funny because it's the same vibe, the same approach like Amadou & Mariam. And also she

plays with this instrument called kamale ngoni which is like the kora but with the low string and also tuned as a pentatonic. So I always tried to play the guitar like the kamale ngoni. So I kind of got deeper into that style.

And now I'll ask about Salif Keita?

I worked on the one before the last album, Un Autre Blanc. Again, this is the magic of Paris. I will say a big thanks again to Cheick Tidiane Seick who really pushed me and introduced me to all these incredible artists. And like when he sent me to meet Amadou & Mariam, it was same thing with Salif. Salif was looking for a guitarist. And Cheick was like, “Hey, I have my boy." And Salif said, “Yeah, well, your boy, they told me he's a jazz musician. He cannot play groove.” And Cheick was like, “What? You should call him.” And then Salif went on tour in Europe, and to whoever he'd ask, “Do you know Hervé Samb?” And everybody was like, “Yeah, man. Yeah." So he came to see me and said, “It's like everybody knows you. Every time I say your name, everybody's like 'Wow.' So I'm like, I need to hear you play.” [LAUGHS]

So you recorded one track or the whole album?

Almost the whole album because he decided to do this album on his own. And that was the first album he did without a European producer. Most of his albums, he'd come to do it in Europe and have all these producers that sometimes the label kind of like told him to use, but this time he decided to produce his own album. He decided to do it in Mali in his own studio. So he flew me to Bamako, brought me to the studio, and I remember his son was the engineer and co-producer. And he left me with his son because he was too stressed, because maybe he didn't know how I was going to work out. That's how I analyzed it; maybe it was something different. From time to time in the day, he'd just come and listen, and say, “Oh yeah, sounds great,” and then leave again. But then on the second day, he listened to it and he was so happy that he gave me a guitar. He was like, “Here man! I have a present here! Here you go.” So he really loved the session; he loved everything.

I think we could spend all day talking about all these people you've played with, but I do want to talk about your own stuff too.

It doesn't matter. I love it. It's like all these people became like friends, family. It's okay, I love to talk about them.

So then tell me something about Jimmy Cliff.

Oh, Jimmy Cliff. Oh, my God. This is one of the greatest surprises that I ever had. I had this call and this guy says, “Hey man, we need someone to help us do a promotional tour.” And I said, “Okay, but send me the music and tell me who?” And he said, “Yeah, yeah, yeah. It's for Jimmy." He just said, “Jimmy,” because they were friends, not Jimmy Cliff. So he's like, “Yeah, I’ll send you the music. It's the latest album. And I'm very happy that you can do this because he usually does a solo promotional tour by himself. But he cannot play the guitar and sing at the same time now. So we figure maybe you can help him.” And I'm like, “Okay, no problem” And then I ask him again, “But Jimmy who?” And this time he said, “Jimmy Cliff.” I made him say again. [LAUGHS] So I'm like “Oh! Yeah!” So there was no rehearsal. I remember I showed up at the radio station studio, he looked at me – I remember I had this African shirt – and he said: “Oh man, I like your shirt. So that means the music should be nice.” I think I gave it to him later. But he was stressed because he'd never seen or heard me play. So I said, “What are we going to play?” He said: “Do you know 'Many Rivers to Cross,' and stuff like that?” I was like, “Yeah, yeah, of course I do.” So then we had like 15 minutes basically to talk quickly. So by the time they put the mic on and we're going live right there. No rehearsal. But he was so happy. I think we spent two or three days together. He really loved the collaboration. Just a duet, and it was amazing. At the time I wanted to propose him to produce his next album actually, because he was quite open. I hope it will happen one day.

And this is at all available to hear?

Oh man, the video, it's on RTL, on YouTube. That one – it's that first time we played together!

I just have more person I want to ask you about

Let me guess... Marcus Miller?

Actually it was Meshell Ndegeocello.

Oh, oh, that's another story. 9LAUGHS) Oh, wow, Meshell, sister. Meshell was something very incredible. I was doing David Murray’s Gwo ka Masters Project playing in New York.

And you wrote one of the songs on Murray's album, yes?

Yes. “Djolla Feeling.”

So we were touring the States and on drums was J.T. Lewis who introduced me to a girl, Kim, who was very good friends with a girl named Rebecca. So I'm here in New York playing at the Jazz Standard, like two or three nights in a row, and at second show, just before we go on stage, and J.T. says, “Hey man, Meshell is looking for you.” And I said, “Who?” Then he said: “Man, that's some big thing. You should check her out.” So later, I go back to the hotel and go online and I was like, this is incredible. So what happened was that this Rebecca was very good friends with Meshell who had asked her: “Hey, I need a guitar player who can play African music and rock.” And Rebecca said she knew the right guy and he was in New York right now. And it was just like that. So she listened to the album I had just released, Cross Over, and was blown away. So she called me and asked me to come to record in August, but I was going to be back in Senegal with my family. So they actually flew me from Senegal all the way to Los Angeles.

And if I may guess your next question – “What I did learn from her?” A lot, I actually learned a lot. What I was impressed by was, like, I think I listened to like forty songs. She's so productive and then I was sitting with her and the engineer and they played this song and she asked me if I can add an African way to this song. And I was like, “It was so beautiful already. Do you really need something more? Because this is amazing.” But then I come up with something and she loved it. And then she tells the engineer, “Okay, let's erase everything and start all over again.” So I ended up recording on a click track. But that was the level of creativity. She was like doing things, then erased it all and started all over again. And every song has got such a strong personality, such a strong level of creativity. It could be something different but still Meshell. It was an amazing experience. She wasn't afraid to start all over because she had a new inspiration. And then she flew me back to L.A. a second time to record for 24 hours.

So I wound up getting the credit for writing one of these songs. And then, when I listen to the record and I hear Pat Metheny and Oumou Sangaré on it. Wow.

But this was after you had already toured with Oumou?

Before. I had actually recorded on her album Seya. But she never really collaborated with me because it was through Cheick, who produced the album. But we met at an amazing gig in Brussels where there were so many artists coming from all over the world. And then we spent like one week rehearsing. That's when she really knew me and then toured.

So she was already singing on a song that you wrote.

Yeah.

So let’s take a break and then we'll talk about your own music and albums.

Okay. Sounds good.

TO BE CONTINUED....