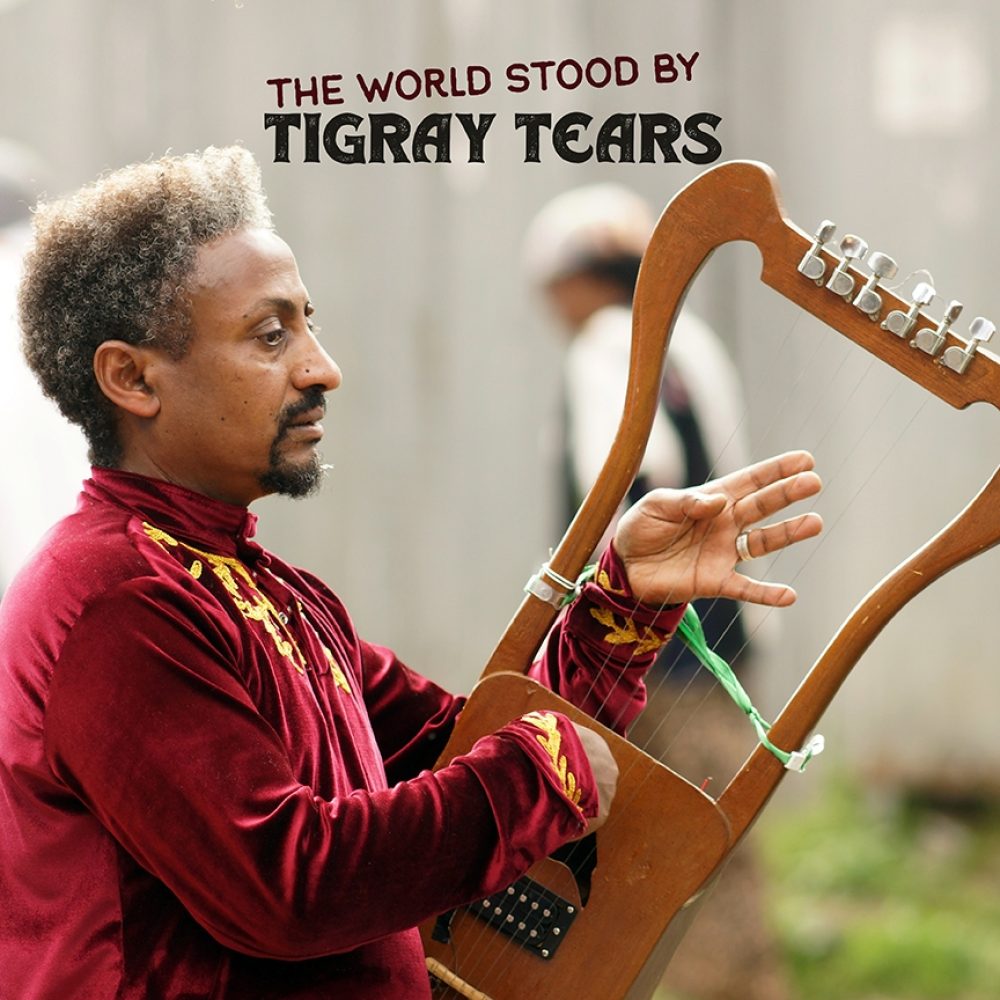

In 2020, war broke out between the Ethiopian/Eritrean federal government and the Tigray Peoples Liberation Front. Tensions had been building in this northern Ethiopian territory, but during the past five years, the situation has become dire. It is estimated that as many as 600,000, mostly Tigrayans, have died, and that “war rape” is a daily occurrence, victimizing girls as young as eight years old. Given all that, it’s no surprise that when author and music producer Ian Brennan and his photographer wife Marilena Umhoza Deli traveled to Ethiopia to record Tigrayan musicians, they had to tread lightly.

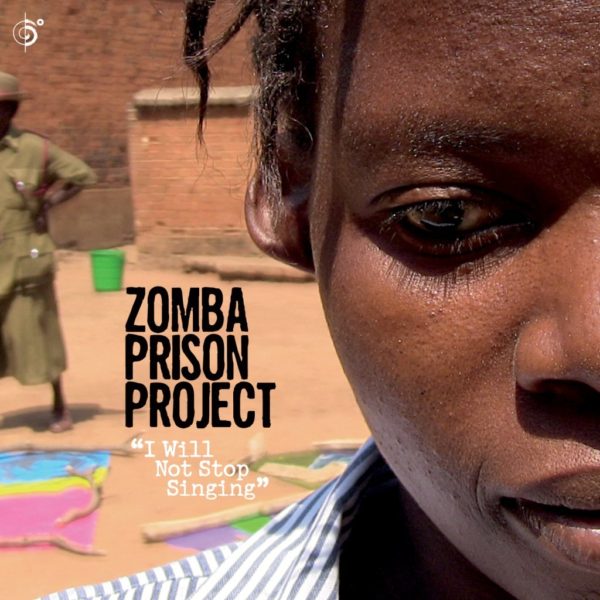

Brennan and Deli have an impressive catalogue of unlikely music projects. In 2011, Brennan extended an already impressive roots music producing career when he earned Grammy for his work on the Tinariwen album Tassili. Since then, he and Deli have traveled the world documenting underrecognized roots music from the Zomba Prison Project in Malawi, to Sudanese street musicians, funeral songs in Ghana, songs by albinos in Tanzania, Mississippi prison gospel, and projects in Bhutan, Surinam, São Tome… It’s a long list. To say they prefer music off the beaten path is an understatement, but sidling up to a hot war zone posed unique challenges for even these intrepid veterans. The digital album Tigray Tears: The World Stood By does not identify performers by their full names. They remain shrouded, adding an aura of mystery to these intimate recordings made in Addis Ababa by musicians in exile.

What we hear are haunting, at times growling vocal performances, mostly accompanied by the five- or six- string East African harp, the krar. Song titles like “No Matter Where I Am, I Miss Tigray,” “What Is The World Saying About Tigray?” “Remembering the People We Lost in the War,” and “People Should Live in Love” testify to a troubled people, holding firm to ideals of love and peace, despite disheartening circumstances. With titles and performances like these, no translation from the Tigrayan language is really needed.

Afropop’s Banning Eyre spoke with Brennan from his home in Italy. Here’s their conversation, lightly edited for length and clarity.

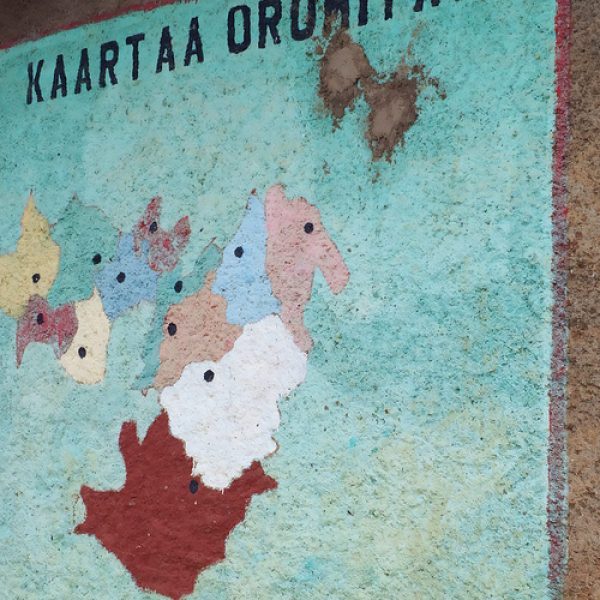

Tigray photos by Marilena Umhoza Deli.

Banning Eyre: Ian, I am continually amazed by your productivity. I keep coming across these remarkable projects and thinking, “I bet this is Ian,” and sure enough, it is! So tell me about Tigray. How did this one come about?

Ian Brennan: Well, you know about the conflict in Tigray, which is ongoing, reemerging and then, hopefully, deescalating. But the threat of it becoming full-blown again has been very real this past year in particular. This has been labeled as the most underreported conflict in the world, and like so many conflicts, I’ve found many people don't even know about it, even though Ethiopia is the second most populous country in Africa. And these are pepole who are engaged; they're not people who ignore the world. But there's just a lot going on in the world, and here was this huge conflict that very few people seemed to know about. So we were interested in just meeting people and hearing from the community about what they wanted to communicate.

You recorded in Ethiopia.

Yes. We weren't allowed to go to Tigray as foreigners. That is back in effect from the Ethiopian government. If you're a foreigner, you're not allowed to go there. So we recorded in the capital with people from the community. Some were there for greater success or opportunities; others because of the conflict. And then we went north to Amhara, where a lot of conflict had just occurred even more recently, and was technically ongoing. A lot of people from Tigray had fled to Amara, and we recorded people there, but that developed into another recording, which is a religious recording. People there are so religious, and that was quite moving, you know, to see the commitment people had getting up before dawn to go to mass and sing.

Tell me about the musicians on this album, the ones in Addis. What kind of people are they?

You know, like a lot of projects in our experience, you meet people by meeting people. One musician leads to another musician, and sometimes that's a dead end, because musicians sometimes aren't very good judges of other musicians. Sometimes they're really insightful, and you’ll have some superstar musician that'll turn you on to something good. But a lot of times, they'll turn you on to something and you think, “Wow! Maybe that’s not part of your talent.” They'll lead you to somebody who's more artificial. Maybe they are not objective because that person was influential to them. Or maybe that person is more successful than they are locally. That kind of thing. That's what happened. There was an auto mechanic on the record, by trade, and you know, and everybody was like, “Oh, no, but you're really lucky because we're bringing in this other guy that’s his friend, and he's famous. He's been on television.” Okay, cool. And the friend was good. But the auto mechanic was amazing.

It’s a short album, just eight tracks.

Yes. It's a very simple, modest record, unlike a lot of things we've done. This was just an intimate sketch of people in the Addis community. That's why the recordings in the North ended up really speaking to something separate from this.

Some songs are very short, and very simply recorded. You feel it’s a person performing for a single microphone. Talk about the aesthetic of the album and your role as a producer in taking these raw recordings and turning them into an album.

In general, I try to do nothing, or as little as possible, to let people speak for themselves in the recording process. It's begun just with the eagerness to want to communicate with people and learn from them. And then there's a point where maybe it seems like, “Oh, this could actually be something that other people would want to listen to.” It's nice when that happens. But that's not the goal.

On the song “My Heart Pleads for Your Forgiveness,” I hear a kind of warbling effect near the end. You must have done something there.

Yes. That is a live looping experiment done in the field with him, one track dry, the other looped. There's a lot of stuff that we record that'll never be released. It's good, but it just doesn't have that substance. So once that happens, then my focus becomes, “Okay, let's make sure that there's enough color that this will hold up.” And that’s difficult, because they're playing a fixed-tuning instrument. The krar is a stringed harp with a fixed tuning. And you know, there are different krars on the record. So they do sound a little bit different from each other, but that's almost always a concern. It's like with thumb pianos. I'm sure you've encountered this. They're found in different places, with different sizes, and tunings.

It's like with the Acholi Machon record from South Sudan. You know, these guys oftentimes play with an orchestra, not just the duo, where there's six or seven of these, going from tiny to more than two feet long. But in the end, you know, every song is still in the same key. You can't get away from that. So this was similar in that way. For me, the voice is the face of the sound. The a acapella stuff, when it works—and it doesn't always work—but when it works, I think there's nothing more intimate than that.

Yes. It’s direct to the heart.

Yeah, so direct and pure. And visceral, I think. You know, one of the origins of all music is the human voice, and singing without accompaniment.

To what extent are these pieces that these singers have written, composed and performed in a fixed form. And to what extent are they just spontaneous creations? I'm looking at a title like, “What is the World Saying About Tigray?” To what extent is this message premeditated as song lyrics, and to what extent is it something that just came out in front of your microphone?

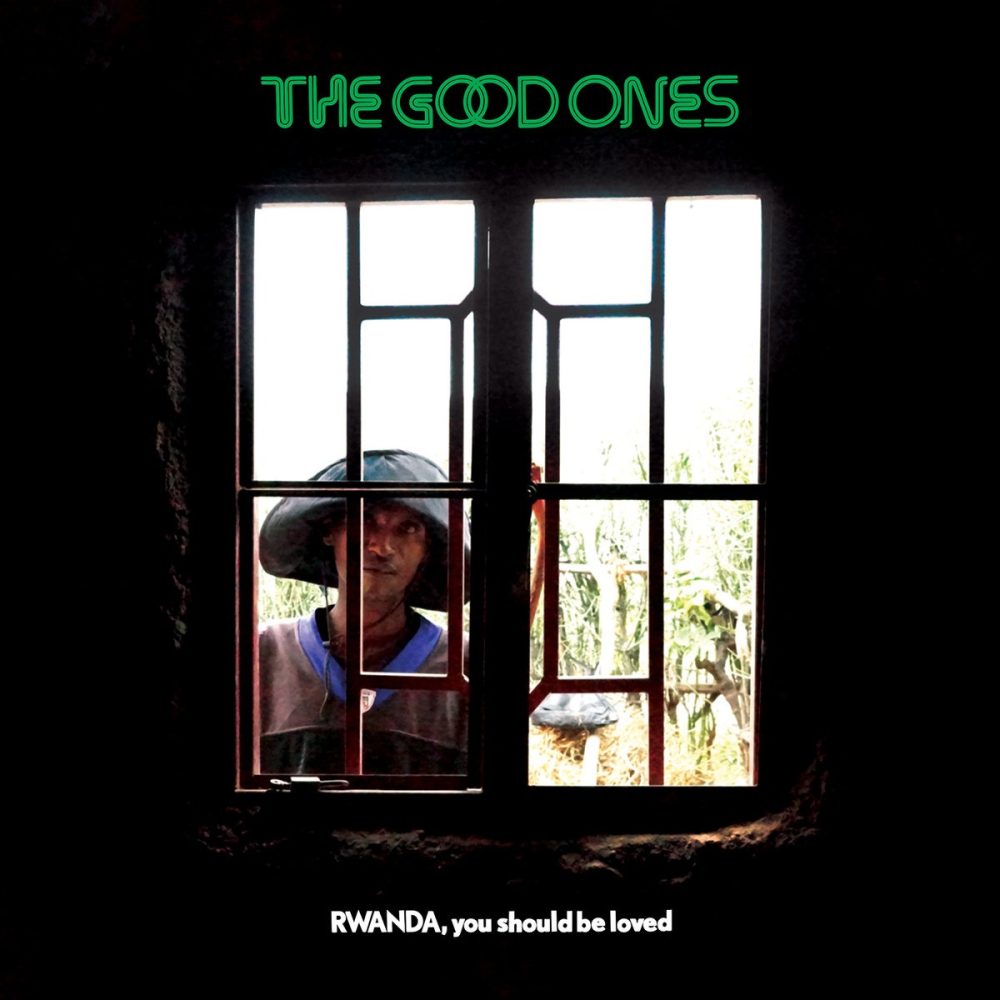

That's a good question. I mean, a lot of the records we do are improvisational with people who have never written songs, and maybe never sung, or don't consider themselves singers or songwriters. And some amazing things can happen that way. These people had written songs. Our only direction is, “You do whatever you want, express whatever you want.” And so there was a pretty consistent focus on Tigray and the conflict, hence a song like “What is the World Saying About Tigray?” Because they're very curious about what people are saying. Do people even know where we are, what we are? What's going on? The moving thing with them, and with The Good Ones from Rwanda and so many other artists, is how much they sing about home, whatever their home is like. It might be a place derided within their own nation, maybe a rural area, or a “poor” area, a less desirable area. But it's their home.

It's also moving how much they sing about love, and the complexity of love. There's a song on the record about being divided by culture. That's hardly unique to any one country. I think that's everywhere, even in “democratic” or “enlightened” places.

Yes. That’s more and more true here, actually.

Yes. Well, it's easy to fall back, you know. You think that there's progress, but if you look at history, there's often been progress…

And then there's backsliding.

Yes, not maintaining it, falling back into those divisions, you know. So there’s a song about “my love is from a different culture.”

I guess that's a heightened experience for Tigrayans. Maybe it would be good to talk about the dimensions of the conflict. We did a program from the Oromo perspective. What is the Tigrayan take on what they want, what they're fighting for?

Well, I would imagine it depends on who you talk to. I think the average person just wants peace, and to have their perspective and their culture honored. I don't think for most of them that's a matter of politics, or political independence. It's more just, “Don't bomb us; don't shoot us; don't attack us. Don't sexually assault us. Don't burn our villages.” I mean, it's more defensive than aspirational. It's just: let us exist.

What I've noticed around the world, and in this case as well, is that most people are just trying to get through the day, economically, emotionally and otherwise. They care about these things. But a lot of these conflicts come down to extremists. You've got one group that has really strong ideology, and you've got another group in power. And then you've got the people trapped in the middle. And that's where people start using the word genocide, and talking about hundreds of thousands, maybe even a million deaths, and the fact that that's not reported is hard for any of us to wrap our heads around. I think it's hard for us to imagine the scale of these conflicts.

But what I've seen a lot in the places we've gone that are at war is that usually when you're there, you don't know they're at war, unless you're in a certain spot. You don't see the violence. That's not to dismiss it. It might really be impacting huge numbers of people. But it's often in border areas. In this case, it's up there where they don't want you to go. Even in Amhara, we weren't supposed to go. You’re allowed to go, but the industry there for visitors has been completely gutted. The whole area has become economically depressed.

In the airport at Amhara, there were still bullet holes from the attack that had happened a year earlier. They had not been fixed. But the locals all said, “Look, this has nothing to do with us. This is a bunch of guys up in the hills, and they're never going to find these guys.” Meaning the soldiers were never going to find them, because they know where to hide and how to hide. So there were checkpoints, military checkpoints, but that's not going to do anything because these guys aren't gonna come down and try to drive on these roads. They're up there waiting, and they're not the majority. Meanwhile, by their own report, the locals were starving. People weren't coming, and many depended on tourism from within the country itself, and from other places as well. And that was just gone, because once you get that stamp, it's very hard to have it removed. I'm sure you've noticed this as well.

In traveling, it's not that I've become cavalier. I try to be very cautious, and I'm not at all a thrill seeker in that way, but I've learned that when you see these governmental ratings, you can look at the U.S. site, and at the Canadian site, the U.K. site and try to contrast. Is there a consistent evaluation of danger? And they're usually pretty consistent. They don't vary much from one another, but what I’ve figured out is that once you get that danger rating—let's say a level three or level four—that's not going to be taken off for a very long time. Everyone is afraid to be the person who takes that off because then if something happens…

I see. You don’t want to get blamed. In my experience, things always seem worse when you read about it, and then you talk to people on the ground and it feels different. The State Department might say you can't go to Mali anymore, and yet I know people who are going back and forth pretty regularly. It doesn't mean there’s no danger, but it’s exaggerated. It’s like this thing that just happened in LA, where everyone saw what was going down in a five-block radius and thought the whole city was burning. Same idea. But I'm curious about what is driving this conflict from the Ethiopian side. Why are they conducting raids and raping and pillaging if it's not fear of an independence movement? Is it just pure out racial hatred?

Well, I wouldn't want to speculate. It's quite complicated. But you know, there was an independence movement, you know, with Eritrea gaining independence.

Right, sure.

I think Ethiopia, like America, is incredibly diverse. It's huge physically. And for much longer than the U.S., they have successfully managed this diversity quite peacefully, and had great unity. Part of that was why they were able to be the only African country that was never colonized. Well, they were colonized, but only for a very short time. They were able to defeat the colonists, the Italians, the first time, and the second time. That has been inspirational, and continues to be to people around the world.

You connect that with the historical ethnic harmony that they had. This unity.

Yes. All these different languages and all these different people have gotten along quite well. I mean, the people in Tigray make up I think only 6% of the population. But there are many, many groups that are smaller or around the same size.

You know, with immigration, like from Italy to America, or from China to Italy, you'll oftentimes get people immigrating from the same place. So it gives a false sense of homogeneity that does not exist. So a lot of the people who immigrated to New York City were from Sicily, and some were from Naples, and so most Italian Americans, if they speak any Italian, speak a dialect from Sicily. Here in Italy, I was recently told that the vast majority of people from China that are living in Italy come from one village. That's the way immigration tends to work.

Interesting.

So that often gives a sense that nations are not as diverse as they really are, and of course the diversity within Africa is greater than anywhere else in the world. In a single nation, especially one as massive as Ethiopia is, with its incredible history, the diversity is enormous. So in many ways, the peace that they have had is remarkable. Obviously, they've had a lot of problems in the late 20th century, and now they seem to be more around ethnicity than around politics.

When I think of the fall of Haile Selassie, and the coming Mengistu regime, I don’t think of that as an ethnic conflict. It was more about political philosophy and social stratification, right? But I want to go back to what you were saying about ethnic unity. Do you think that because of that history of having been unified, and having held off colonialism so effectively, the idea of one ethnic group wanting to assert its individuality is kind of inherently threatening, because it goes against that historic strength of unity? Am I overthinking this?

Well, it's an interesting idea. I don't know. I do know that there is a current pride in that memory of fighting off colonialism. They opened a new museum devoted to just that, which we went to when we were there. So it's something that they invested a lot of money in, building this center, this museum, and people go there. So that could be part of it. But I think, I'm afraid, that it tends to come down to money. The average person, which is 99% probably, is just caught in the middle of the capitalists, the people making the decisions, and benefiting from land and resources.

We've been to Tanzania a few times in the last couple of years, and they're having this problem with the Maasai being thrown off their land. Maybe it's a similar kind of dynamic, because the concept of Ubuntu, Tanzanian ethnic togetherness and harmony, runs deep in the country’s cultural veins. So when one group, like the Maasai, single themselves out as being special, it goes against this idea that we’re all Tanzanians.

I've been following the debate about this, and there are people in the government who make this argument, that the Maasai need to think of themselves as Tanzanians, not as a special group. And yet, really, when you dig into it, as you say, it comes down to money. The government has been offered this massive amount of Arab money to create game parks where wealthy folks can hunt lions and rhinos. There’s big money in that, and it’s hard for a government to turn it down. So it's complicated.

Right. Right. Tanzania is another example. I think that even the physically small places, you know, the Comoros or Djibouti, they have their diversity too, much more than people realize. But when you talk about these huge pieces of land with complex histories that have been completely interfered with by colonial powers, and now capitalistic powers, which is more or less the same thing in a different form... There’s all kinds of violence that continues to resonate. You know, when I did the Tinariwen record, we did it in southeast Algeria and it was mind-opening to me to see how big Algeria is. I'm trying to remember the exact correlation, but I think Texas, and then a few other states would fit in there. That's how big it is.

And it’s very sparsely populated.

Yeah. Most people are on the coast, like so many places. They're up there on the Mediterranean.

So coming back to Tigray Tears, what can you say about the music itself? How is it like or not like other kinds of Ethiopian music that we may be more familiar with?

Well, for me, it’s hard not to hear echoes of “desert rock.” You know? There's some cyclical, hypnotic stuff happening in the krar playing that is very reminiscent of Tinariwen and others. It’s hard to believe that there isn't some connection. Even though they're quite distant geographically, they're not that distant. I believe there's a lot of parallel invention out there. The pentatonic scale is kind of everywhere, not because people picked it up from somewhere else. It's just sort of a natural thing that is gonna emerge when people are expressing themselves musically.

I try not to think too much in those terms, you know, making these connections that might be arbitrary. But I have noticed that at high altitudes, a lot of times there will be this kind of atonal choral singing that is almost psychedelic. And maybe that has something to do with being up there with less oxygen.

Well, I do think the environment influences music. Desert musics around the world share certain characteristics. So is this Tigray music mountain music? Is Tigray high altitude territory?

I'd say it's medium altitude. But there's the element of high desert too, and that's what maybe where the connection with the Saharan groups that aren't aren't so far away comes in. And of course, they’re moving closer all the time with the expansion of the desert itself.

There’s another factor that our friend in Ghana John Collins talks about. It’s very hard for us living in the wake of colonialism to appreciate how restricted travel became with colonialism. There was just a lot more fluidity of movement before those states and borders got drawn not so long ago. So connections and interactions that seem improbable now might have been much easier in the past.

Right, without the borders. But now with digital music and commercial distribution of music, I think there's a tendency to entertain ethnomusicology fantasies, or to read influences that aren't there. I think that can happen. I've seen that happen with American artists. I'll read a review of somebody, back in the eighties nineties where somebody would be saying, “Well, they clearly were influenced by…” and they’re name dropping some obscure record. And I'm like, “No. I know this person and they've never heard that record.” Maybe there's some similarity, but it's never that clean. It's not quite the way people want it to be.

I think it's really hard for us to grasp to this day how limited many people are in terms of their access to the Internet, and also how little interest it holds for them, beyond whatever practical purposes it serves. For a lot of people, cell phone is to communicate with family and friends, and they don't want to be wasting minutes looking at shit on the Internet. And they're not listening to music a lot. Some are, of course, but a lot of them are not.

Over and over again, I've been amazed how resistant people are to the idea that an artist doesn't know who the Beatles are, or doesn't know who Angelique Kidjo is. But it's just the reality. You know, The Good Ones have an album that's coming out, and we were in New York City before they did the Tiny Desk. We were walking around Greenwich Village, and we ended up doing photos on the street where Bob Dylan shot the cover for The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, right? But The Good Ones have no idea who Bob Dylan is. They have no idea. They play music that's in the ballpark, in many ways, in the tradition of folk music. But they don't know who Bob Dylan is, and if I played Bob Dylan for them, which I never have, they'd probably like it, you know. But maybe not. Maybe they'd think his voice is weird.

It would be hard for them to appreciate all its implications.

Yes.

That’s interesting. But, you know, I do find that urban Africans are often surprisingly knowledgeable about all kinds of things, because they spend hours watching stuff on YouTube.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. It's the urban-rural divide.

I interviewed a young Nigerian producer/pop musician recently, part of the whole Afrobeats world, and someone had just turned him on to Robert Johnson. He’d never heard anything like it and said, “I gotta do something with this.” It was this cool new thing he had just discovered.

No doubt. It's just that urban-rural divide. I think this is the thing with the Grammys. They've tried to improve in this area of global music…

They’ve got a ways to go.

Yeah, it's very difficult for that to happen because they're talking to the 1% oftentimes in other countries. Nothing wrong with that, but they're certainly not hearing from the masses, from rural or traditional artists, because a lot of those folks don't have electricity. They don't have access to to media, and yet they are half the world's population.

Those are the people you are particularly interested in recording, right? You seek out those hidden and overlooked talents.

Well, yeah, I mean I seek roots music, whether it's from America or from anywhere else. I've always gravitated towards that, and I feel like I understand it. But then, in terms of representation, I always feel that if somebody doesn't need my help, that's great. That's fine. I don't need to do anything. And so when some “global music” people come to me and say, “We want you to produce our record,” I'm like, “Okay. But why? What can I do for you when you're already doing great?”

I have a specific way of making records, and I believe in that. But I don't believe it's for everybody. There are people who are really just ignored or denied. Because of my background, having grown up with my sister who was a year older than me and who was disabled, I’m used to seeing people being marginalized and invisibilized. I've always been interested in siding with the underdog, providing a voice for any under-represented or unfairly represented people.

Within each nation, there are going to be those folks. In America, it’s often the disabled, the homeless, the elderly. Everywhere, there are people who are being denied. But when you see entire countries being essentially erased, or, in the case of the conflict in Ethiopia, a conflict where so many people have died and suffered all kinds of victimization, and to see that be almost ignored…

On the one hand, I understand that it's overwhelming for people. There's only so much media coverage can do. But, on the other hand, you see the hyper-focus on certain things, where something will get reported over and over and over and over again, and numerically, it doesn't add up. You see what's considered a tragedy in one case, and what's regarded as inevitable or inconsequential in another case, even though it may involve hundreds of thousands of people versus a dozen.

I am interested that your experience with your sister may have oriented you in a certain way to be sympathetic to marginalized people. Remind me. Where did you grow up?

I grew up in the East Bay in the Bay Area. I was born in Oakland.

So these musicians you recorded in Addis? Are they in exile, or can they go back and forth freely?

I don't think it's easy. I don't want to misstate or say anything controversial with the Government, Beyond any restrictions, which in some cases are in place, there are physical dangers for them, particularly for women going there. There are also economic reasons. It’s not easy to get back and forth.

So these people are living in Addis, not just visiting or passing through.

Right. Some had come in advance of the conflict for opportunities in the city. Some had come because of the conflict. But when you're talking about going back and forth all the time, no. Almost all of them have loved ones there, and that keeps them very focused.

“No Matter Where I am, I Miss my Homeland.”

Yes. That keeps them focused in a very palpable way. You know, I was in an Uber in the Bay Area when I was last in the U.S.. The driver was from Eritrea, and he was telling me how he hadn't been able to go home for 18 years. He had been in the U.S. for18 years, and his wife, his daughters were still in Eritrea. And this is before what's happening now with ICE now. It’s hard to imagine the isolation and loneliness that many people suffer and are subjected to, based on global politics and economics.

Are there any of these musicians that you might want to highlight, or that were particularly memorable?

Well, if they're on the record, it's because I feel like their voice really conveyed something. That tends to be my focus. I do believe in this idea that most people have one good song and only one good song in them. So everything becomes kind of a carbon copy of that. And I think so many artists in the West, there's occasionally a song, and it's like, “Where did that come?” They're brilliant for three minutes, and then never anything even remotely close to that again.

Sometimes it’s industrial, meaning that it's not really them. They brought in a bunch of studio players, and they probably had some ghostwriters and whatever. But a lot of times, it really is them. It's just that moment where everything clicked and they found that zone that is transcendent.

Hmm. I do a lot of solo guitar composition, and sometimes I feel like I'm constantly rewriting the same five songs.

But maybe it gets better each time.

One hopes.

So to answer your question, of all the folks on the album, the auto mechanic stands out. It was that classic recurring experience that we've had where the person is not a singer, but they’re great. It happened with The Good Ones. People said, “Don't record them.” Literally, while we're recording, somebody came up and started banging on the wall, trying to interfere, like they were offended by the way they were dressed, or offended by their accent and the type of music they play. All this stuff. And yet some of those same people now have no memory of that. Now they love them because they've had success, even though it's very small on the big scale.

All a matter of perspective.

We've had that experience so often, and often it's the artists themselves. This auto mechanic was so convinced that his friend was much better than he was, and his friend was good. His friend was fine, but he was better. He was just so unique and unaffected.

Well, it's great to talk with you. Anything else you want to say about this particular project?

Just that, as always, we were very blessed and happy to meet these people, and for them to share their voices and stories with us. I think it just comes back to how much universally people want a home and want love, and that's what they tend to sing about, regardless.

You have a good relationship with the Glitterbeat label. I expect a lot of labels wouldn't give your projects the time of day.

This record is not with Glitterbeat. This is just something I put out on the little label I've had forever. But the relationship with Glitterbeat has been great. It was a perfect kind of convergence. When they started thinking about doing their Hidden Music series was right when I came in contact with them. And we’ve gone on to do, I think, 15 quite diverse records from places that otherwise had not had original music widely released, places like Comoros and Bhutan and Surinam.

Well, keep it up, Ian. You’re one of a kind!

Thank you.

Related Audio Programs