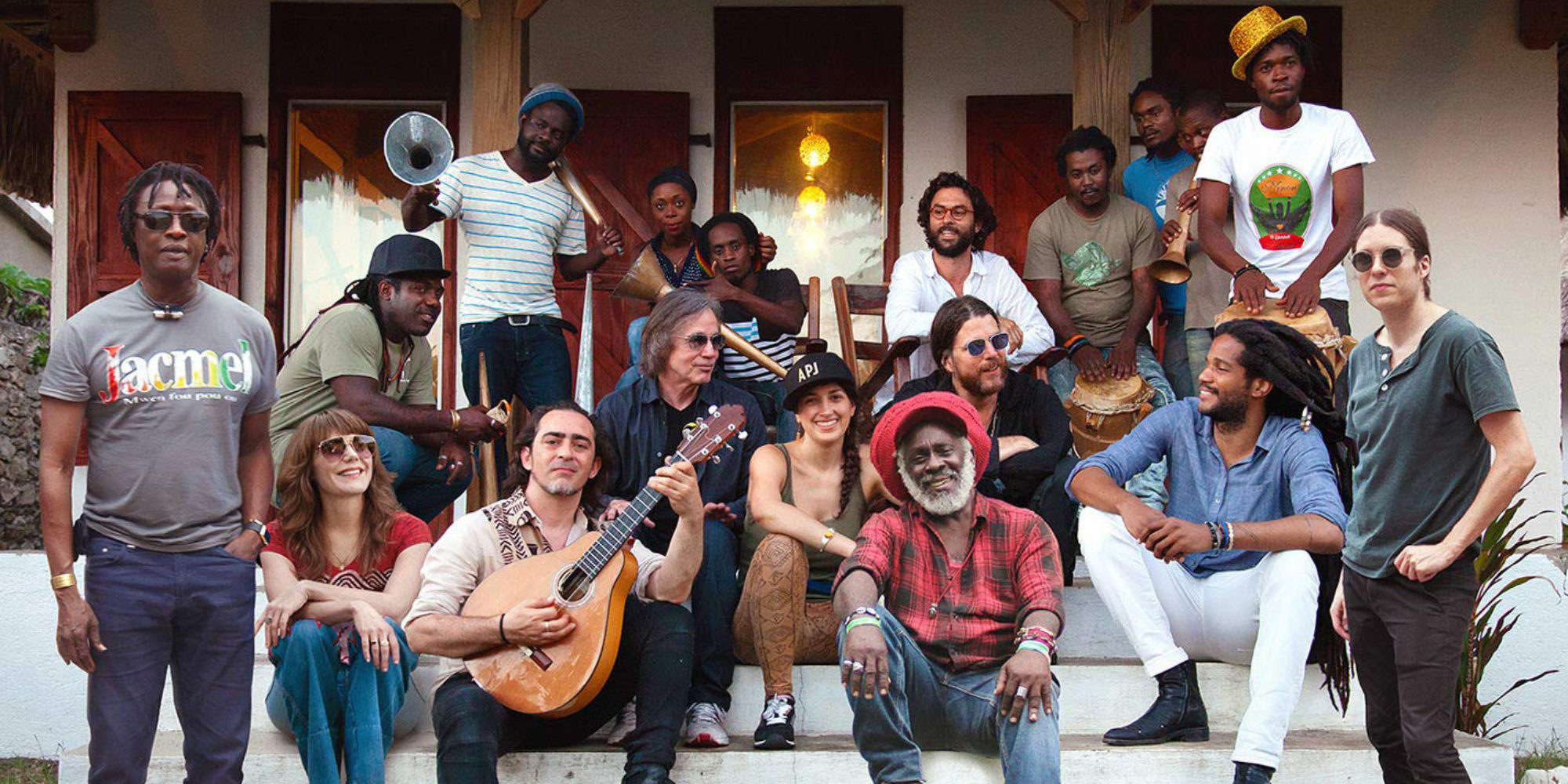

Jackson Browne has been a prominent figure in American popular music since the 1960s. A Rock & Roll Hall of Famer with over 18 million albums sold, and the author of enduring classic rock songs, Jackson also has had a long career in social activism. After the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, Jackson began supporting relief efforts there. The bond has grown over the years. In 2015, he initiated a project that led to an unusual album of songs called Let the Rhythm Lead: Haiti Song Summit Vol. 1. The album is a diverse collaboration involving fellow American musicians (Jonathan Russell, Jonathan Wilson and Jenny Lewis), friends from afar (Raul Rodriguez of Spain and Habib Koite of Mali) and a number of Haitian musicians including Paul Beaubrun and the band Lakou Mizik.

Afropop Worldwide first met Browne in Mali in 2000, during the Afropop’s memorable Mali Magic 2000 listener tour. On hearing Let the Rhythm Lead, Afropop’s Banning Eyre wanted to know the story of the project. He reached Browne by telephone from Los Angeles, and Browne was most generous with his time. What follows is an edited transcript of their conversation. This interview occurred just at the start of the coronavirus outbreak in the U.S. We have since learned that Browne himself tested positive for the virus. Happily, his symptoms are mild and he is recovering.

Banning Eyre: Hey, Jackson, thanks for making time.

Jackson Browne: Thanks for your interest. It's an exciting project, and you had some presence right at its inception because of your proximity to Habib Koite, and Bonnie [Raitt] on my trip to Mali.

Habib was the first person who told me about your Haiti project. But then, subsequently, we did a program with Raul Rodriguez about "The Hidden Blackness of Flamenco." And more recently, we have been speaking with Paul Beaubrun. In fact we just saw Paul playing live the other night at S.O.B's in New York. Rocking out.

[Laughs] Yeah, we got to see him play at a club in Port au Prince, and it was really interesting. He's such a monster player, powerful, and with such a muscular rhythm section.

And it's funny, because he's such a sweet guy. You don't expect that.

Yeah. He's got a very loving, sweet, respectful vibe. So considerate. And I guess you know his parents, Lolo and Mimrose from Boukman Eksperyans.

Sure. We go back. But let's talk about your project. How did it all get started?

Right after the earthquake in 2010, I was at a fundraiser for a group called Artists for Peace and Justice [APJ]. They were raising money to rebuild a school in Cite Soleil in Port au Prince, Haiti. This was in one of the poorest, roughest neighborhoods, and Haitians are the poorest people in the Western Hemisphere. So APJ wanted to build a school that was safe and well-constructed.

A lot of people on the board of that organization are film people like Ben Stiller and Susan Sarandon. Paul Haggis was the guy who started it. They did wind up building a school, in record time, counter to the popular understanding that no NGOs were able to do anything with the relief money. Maybe it was because they are used to doing things on production schedules. Because if you’re making a film, you just find out who can do it and get it done. There's a can-do attitude of people in that business. They built an infrastructure, and the way the school is structured, everybody they hire on the outside will work there for only five years, and then be replaced by a Haitian.

How's the school doing now?

Well, it's been growing for ten years. As of January, 2020, there were twenty-six hundred kids going there for free. However at the moment, due to civil unrest the school is shut down. The school connected with a priest named Father Rick Frechette. He's built hospitals and he was instrumental in getting the land for the school. There’s also a guy named David Belle who has lived in Jacmel part of the year for many years. David created an arts festival there, and he was part of an arts collective and an effort to get artists in Jacmel representation in some kind of a union, a place where they could sell their work. His know-how had a lot to do with how APJ ended up with a recording studio and a film institute in Jacmel; that's the Audio Institute and the Cine or film Institute.

They teach the best and the brightest of these kids who want to go into the arts. These kids would otherwise be working to help support their families. They are money earners. But instead, they're in school, because they're serious about being professional musicians and professional engineers.

So you went down to record in that studio?

Yes, but we didn't go down there with the express purpose of making an album. The way it started was simply through APJ, which is a 501(c)(3). I was able to give money that was generated through my concert ticket sales. There's a way you can give a dollar from each ticket you sell to a 501(c)(3). It's just a pass-through, so I donated money from about a year's touring for this project. That's how we got the money to fly Raul and Habib from Europe and Africa.

I had seen the studio on an earlier trip. It's a very nice studio, but it's basic. They considered it state-of-the-art because it's a brand-new SSL board, brand-new ProTools. But it was entry-level from our perspective. But the music they were making in the studio was great. So I thought, "All you really need is for artists to come from all over the world and record here and create an opportunity for the students to learn how everybody works.” There are so many different styles of working, so many different ways of making a session happen, so many different ways of miking. They’re very advanced musically and rhythmically; they just needed to have hands-on experience and to see somebody experienced work in their studio.

They’re doing the same thing with film. In fact, the videos that we made for this record in Haiti last fall—We made them with graduate students of the Cine Institute.

Before the trip, Jonathan Wilson, my co-producer for the album, and I went shopping. We looked at their list of gear. We got some microphones donated. We brought everything from microphones to drum heads, compressors and limiters. Analog gear. And when Jonathan hooked it up and they listened to the drums, they went, "Oh, we were wondering how you do that."

It’s funny. When we went through Customs down there, they would look at us like, "O.K., what is this?" Customs officials have books of various products so they can look up what things are worth, because they expect people to lie about what they're bringing into the country. So there was this moment when they opened these boxes and saw all this brand-new gear, but what is it? It's not a TV. It's not a microwave. And we said we're going to the studio in Jacmel and we’re part of this recording project at the school…

Of course they didn’t know anything about the school, and they didn't know us. So we asked Erlantz Hipolite one of the school founders who had met us, “Is it a problem that we didn't declare this stuff?" And he said, "Well, it's a problem, but it's not your problem." And he goes into the room with the guy to negotiate what we’re going to pay. And he comes out and it's O.K. We can go. So then we wanted to know how much it cost them. I mean the stuff is worth thousands of dollars. And he said, "I bought them lunch."

[Laughs] That was kind of them.

Well, he told them about the school. You know, everywhere we went, we were greeted with love and enthusiasm and respect. Because of the people we were with. With David Belle, Kathryn Everett, Erlantz Hipolite. People who knew about the school knew that anybody they bring down there is doing something good for Haiti.

So you went there with the idea of exchanging studio expertise and helping these artists get a leg up. It was not about making a record.

No. I'm a little bit leery of that. First of all, you don't know what's down there. You don't know what is going to be like. But it was about recording. Jonathan [Wilson] is one of those guys who you can call him up and crack open an idea, and then he'll call you back a week later and say, "So we gonna do that? When we gonna do that?” He's very open to adventure.

Jonathan was kind of the kind of linchpin to all this musical success. He's the one who invited Jenny Lewis. In the studio, he's the kind of A-type, the guy who knows exactly what he wants to do next. And down there, his thirst for trying stuff was huge. We hooked up with the hand drummers and everything we found he wanted to dig into.

We went to see Lakou Mizik perform on the night before we started recording. When we arrived in Jacmel we had a great meal at David Belle's house, and then, right up the road there was this club, and Lakou Mizik was playing. And they were incredible. Oh my God, just so great. They began with this Haitian choral music, and then there was such a profusion of drums. Raul [Rodriguez] was in heaven. He was hearing rhythms that he knows the origin of, because he's a musicologist. And then Jonathan was saying, "We want that guy." Basically, it was like going to the market. Right away, he wanted [Samba] Zao, who is kind of the patriarch of that band. And we’ve got to have Nadine, one of the singers. We just wanted these folks close by when we were recording to come because we didn't know exactly what we were going to do.

The first song we recorded was Jon Russell's "I Found Out." At first Jon started to do what he does in the studio with his band The Head and the Heart--this cool American indie band--which is you double track the vocal yourself and play lots of overdubs. And it took about a day of letting him try out that stuff, but then he started using some of the musicians that were standing around and it became more of a group experience.

So this was the first of two recording trips, right?

Yes. We went down there twice, for about a week each time. The first trip was in April, 2016. The second trip was in November, 2016, right after U.S. election. Habib [Koite] came that second time, and when he started to sing, if you could've seen the faces of these engineers and students. It was like the sun coming over the mountains. Mother Africa! It was that connection with Africa that they feel so strongly and honor and understand. And it turns out Habib is really interested in Haiti. I think he even opened a restaurant in Bamako called Haiti.

What about Raul?

I had known Raul for many years. He used to play with an artist in Spain, Kiko Veneno, who did a crazy version of "Take It Easy” called “Tu Tranquillo.” This was before Raul was in the band Son de la Frontera. Raul was the flamenco guitarist with Kiko, but his dad was kind of a rock'n'roller, and he started out playing drums. Paul Beaubrun was also a drummer before he started playing guitar. There's a lot of rhythm in what Raul does. If you listen to the lyrics of his songs, it's all rhythm.

Raul is amazing. It was a revelation meeting him last year while working on this flamenco program, and we got to see him do a solo concert on his invented instrument, the tres-flamenco.

Well, you know, his mother is a very famous singer, Martirio. She made a lot of records, so Raul grew up making records. He is a very seasoned studio player. I was a freak for Son de la Frontera. I used to follow them around. So I knew Raul from these earlier bands, but I really saw how he had come into his own when he came and recorded with all these individual artists. His instrument, the tres-flamenco—he doesn't play it like a Cuban tres. It's the tres-flamenco. He changed the tuning.

I remember him saying that he is the best player of that instrument, and the only player.

Yes! Founder and president for life. There you go. He plays these beautiful melodious parts in these sessions. There's a moment in “I Found Out” where he starts playing this figure on the tres, and he wound up doubling it on the flamenco guitar, and then he goes off and plays the solo on the flamenco guitar. There's a moment in the video, where he starts playing and it turns from a tres into a flamenco guitar.

And then Jenny Lewis is somebody who has made a lot of records and been in a lot of bands. When “Under the Supermoon” happened, Habib was there with his guitar. He was playing these answers, and then I said, “Habib, why not sing where you've been playing those answers?” That kind of thing kept happening. Like on “Lapé Lamou (Peace and Love),” with Zao from Lakou Mizik. He came in to play some drums, and then Jonathan said, “Why don’t we have a drum solo here?" And then he plays this breakdown thing. And then Jonathan, "You want to sing something here?"

There's just a magic thing about that place. Each one of the students there, they all sing, they all play drums, they all play guitar, they all play bass. And they all know these traditional songs. So when Zao started singing, they all started answering him.

Subsequently, we were down there filming the video for this song “Lapé Lamou,” but we couldn't get Habib there because it's so expensive. We got him down there for the record, but not for the video. So, some of these scenes in the video for "Lapé Lamou" and “Under the Supermoon,” were shot in Mali. Habib got a cinematographer there and they re-created the scene we had created in Haiti. “Lapé Lamou" was actually the last song was recorded, and we decided to put it first because that was the one that cracked out into this incredible vodun call-and-response. It gets you to Haiti faster than any of the other songs.

“Lapé Lamou”

Was the plan to have the artists write songs down there?

The plan was to come with a song or to write one down there. For us there was no format. We just went down there to record and play. But it became like a songwriting workshop. People were writing songs based on what they were encountering. The first song we did actually became the last song on the album, “I Found Out,” by Jon Russell.

I had met Jon Russell on an earlier trip, and we were visiting a high school in Port-au-Prince. And we each sang for these kids in the class. It was interesting. They were curious. They've been told who you are, but they don't know who you are. They're just told that you're famous and they want to know what you do. So when Jon was singing, I thought, "Holy s***, man. This guy can really sing.” And they loved him.

Then a day later, we were in Jacmel and they wanted to do something with us in the studio. They wanted to film it. And we sang a Bill Withers song. Then later that night, he started making up a song. We had met Paul Beaubrun, and he was playing drums with this rara band. This band had come by to sing and play for us at the dinner. These are just groups of people, not professional. Sometimes they just go down the street performing, just doing it on the highway, and you can get caught up in the rara procession and never be seen again.

Anyway, those guys were playing, and Paul was playing with them, and then Jon Russell just started singing. He's singing these words, and I asked him later, "Was that a song you already wrote?" And he said, “No I was just coming up with it right then.” I so admire that, that really fast ability to create. That was the seed of the whole idea, that maybe we could come down and record that song with the same drummers.

In the studio, I'm often trying to create something that I heard happen once, or trying to create something that I've never heard before, but I don't know what it is. So when you get a clue like that, it’s big. So it took a year or so for us to get down there and make it happen. In the meantime, Jon had made an album, and I asked him, "Well, did you do that song?" And he said no. So I said, "Well, can you show it to them?" So there they we were with that same song, in that same place, starting with that incredible chorus.

That’s “I Found Out.”

“I Found Out.” That was the first day we were recording. And I was ecstatic with the way it was turning out.

What was the moment after the first session when you realize that you were going to make a record?

The first trip we recorded six songs in five days and I thought, "Wow, we have half an album." The more we did, the more we realized: this is the band—a great drummer, a great bass player, and how interesting that everybody can accompany each other.

Some of these people weren't there on the first session, but they were on the second one, so they had the benefit of hearing some songs that had been done down there. The idea was bring some songs that you're working on. Jenny showed up in the second session and she had brought some songs. When she got there, we went to this vodun ceremony in a temple in this neighborhood of Jacmel. And it was so amazing, and she realized she didn't have anything that was going to reflect this experience. So she wrote something the next day, “Under the Supermoon.” She wrote that song in the morning, and we recorded it in the afternoon. And it happened that way a lot. Raul, after that first day playing on “I Found Out,” both he and Paul went back to their rooms and came back the next day saying, "I wrote a song." That's how vibrant the creative impulse was.

You mentioned that you went to a vodun ceremony. What was that like?

First of all, I would not have thought to do that. No. No. They said, "We’re thinking about going to a vodun ceremony." And I'm like, "Really? We are?" "Yeah. You want to go, don't you?” So we go to the ceremony, and it's not a tourist thing. It's not a show. It's worship. Along one wall there are about seven drummers, and then there's a bunch of people in the center around this pole, and there's a mic. There's a guy singing out the main cadences, and all people in the room answer. And that's why when this happened in the studio, when Zao started singing, everybody—the engineer and every student—gathered around him and started answering him.

But in the ceremony, it was very funny. Jenny happened to be wearing a very light colored shirt and pants, and she had a red handkerchief around her neck. We get there, and everybody is dressed in white, and these women have these red neckerchiefs around their heads. Jenny is practically dressed exactly like them.

They don't say anything to us or about us. We were with David, and David was invited to come out and offer a kind of benediction. He pours a little rum on the ground where they've drawn this figure with a heart and a sword. He pours a little of it and drinks a little of the rum and sprays it into the room. And meanwhile, the drumming is going full on: intense, dense, deep drumming, like a wall of rhythm.

Was communication ever an issue?

No. Everything was being translated by Paul Beaubrun and David Belle. They are speaking Creole, not French. And some people spoke Spanish. When Raul wrote “Let the Rhythm Lead,” his Spanish friend said to us, "Wow, I don't think anybody realizes how incredible these lyrics are." So I had him translate the song for me into English and I from that, I created and sang an English verse: “When you're lost out on the road, and you're nowhere near your home, let the rhythm take you to the place where you were born.” It's about living your life in an authentic way, in a way that you can respond with power and authority in your own life. That's what the music has always been good for, but it’s particularly so in the context of a world that's coming unraveled now.

It seems like Paul Beaubrun was an important player in all this.

Paul magically became our bass player, because from the first time he picked up the bass, he just put the whole thing in this incredible rhythmic undercurrent. He found the rhythm that wanted to come out of the song, so he became our go-to bass player. Jonathan Wilson is playing the drum kit, but he's playing it in a way that's creating a setting, or a platform, for the hand drums.

My feeling about percussion for many years was you're adding something on, instead of having it be the fundamental. I learned that lesson quite late in life on recordings by Shawn Colvin, produced by John Leventhal. Listen to this percussion on those records. It's the spine of the whole song! That's what's going on with Jonathan’s drumming here. He's playing a bass drum part that is a sonic foundation, but it’s as if he's got eight arms, with all those other guys playing parts of his kit. I love that about this record.

Like Jonathan’s song, “Goddess at the Wheel.” He didn't even play drums on it, he just played guitar, and we had some of the hand drummers from Lakou Mizik. His song is very literal. "There's a new friend on the conga." It's about being grateful for getting to be there. To me the great moment in the song is when he says, "I've never been to Haiti although I've been to Spain, and I can tell you brother, and I know we’re all the same." That for me is a big emotional core of the whole album, the fact that we find this common ground. There's another part in the song where he says, "This ain't California." And I thought I would do this kind of faux Beach Boys harmony behind it. He thought that was corny. He wouldn't have it. [Laughs]

But there's something about being there that's more real than the structured life we have in the United States. It sounds preposterous to say that, but there's some kind of enforced anonymity here. There's a way that we are. Maybe it's conventions or politeness, but we walk around in the city full of people who are strangers to each other. That doesn't really happen down there. You're around people who look right into your eyes. As a first-world tourist, you might go places without meeting anybody, but local people go about their business knowing who each other are.

Let me ask you about the song you wrote for this project, “Love Is Love.” I have to say, this song reminds me a little bit of Bruce Cockburn. There's a flavor of his travelogue songs in there.

Ah! I appreciate that. I thought about him the whole time we were down there. Bruce is the kind of guy that travels all over the world and write songs about where he's been. He's kind of a master of that, bringing the place back. He's written songs about Latin America and Africa…

…Tibet, Mozambique. Even Mali.

And it's political, it's really about what that place is. I thought about him. And then the rhythms. Because his time is amazing. He's one of the most incredible guitar players.

It's true. I grew up in Montréal with his early music. He was one of my first guitar heroes. But back to “Love Is Love.” Did you write that song down there?

I actually started it in L.A. with a little guitar lick. Like I say, have a lot of trepidation about going into these situations where I’m supposed to deliver something in a short time. I'm always trying to reduce expectations and be noncommittal. But there I was inviting people to do this, so I did go down there with a kind of a guitar lick and the idea of the first verse was very much to be sketching out a picture of the place. Something about the weather and the beauty of the place.

Tell me about the song "Saving Grace."

That was actually the one song that was not recorded in Haiti. We did that in my studio in L.A.. So it's the only one that doesn't have Haitian drumming on it, but it does have Paul Beaubrun on bass. It was written on the last day we were in Haiti, and there was an electrical storm and the studio went down. And they were trying to to make sure the electricity would not come back on with a surge, destroying all our work. It was humid, and there was this incredible light in the sky, a lightning storm. Thunder and lightning. That's why there’s that line about "There's a spirit in the air tonight. Coming from all sides. Like lightning in the sky."

In the control room, everybody was listening to the work that we had been doing, and making roughs of everything. They were organizing the drives so that the work would be accessible when we got back. We were to go to the airport at six in the morning or something. So we worked late into the night, and it was during that time this electrical storm happened. So Jon Russell and Kathryn Everett, who was our facilitator from APJ--and so much more, almost our muse--they just sat down and wrote that song. But we had to record it here. It's a very pure moment, and it captures the way we felt down there, getting a chance to do something good. “The time is now to find our saving grace.” It's very emotional for all of us, that song.

I noticed that the title is Volume One. Is that because there are more songs? Or are you planning to go back and record more?

That's because I want to do it again, but I don't know how. I think that everybody on this record feels like we became a band, and we could do any number of things.

I asked Paul if you're going to do a tour, and he kind of rolled his eyes and said that would be very difficult because everyone has these complicated lives.

It’s true. Everybody's got their own career and busy schedules. I have tried several times to make something like that happen. We wanted to make recordings of us performing the songs. We had films of us making the songs, but they still didn't show one person singing the song all the way through, so we needed to film us performing the songs. I tried, and I almost made it happen, but it was going to be extremely expensive to get everybody in one place again, especially in the United States. And we need Lakou Mizik to play these songs. Lakou Mizik does play in the United States, so if we're clever, we may be able to arrange a concert that would coincide with one of their tours.

I imagine you've heard the album that Lakou Mizik made in New Orleans, Haitianola.

Yeah. well, you know, that might be a way to do it, focus on New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, give us a few days to run through songs.

There you go. Haiti is really finding a home down in New Orleans, with people from Arcade Fire living there, and all those deep historical connections. We have done programs about that. Ned Sublette calls it The Fertile Crescent between Haiti, Cuba and New Orleans.

Sure. The free Haitians coming to New Orleans to create this community of artists and merchants in the middle of the segregated South. It's an amazing history, and of course it still being played out. The Haitians are still paying for their freedom.

Prior to this project I had written a song called "Standing in the Breach.” It was a song that I wrote on the eve of playing this benefit for the earthquake in 2010. I tried to include a my last verse, which says, “The unpaid debts of history, the open wounds of time, the laws of human nature always tugging from behind.” It's the idea that Haiti embodies the best in people, their ability to respond to and survive these disasters is really very moving, but they also have an endemic class system that's hampering their very survival in a basic way. So you have the best and the worst going on at the same time in the same place.

We all have an opportunity to involve ourselves in the situation. I've met so many people who've gone to Haiti, trying so hard to make a difference there.

My sister went to Haiti back in the 1980s, fresh out of college. And she had a very intense experience there, which left her feeling powerless to make a difference. So she came home and became a doctor. Years later, she went back after the earthquake to volunteer there.

That's what happened to Father Rick Frechette. He went there as a priest and said, “These people don't need a priest; they need a doctor." So he went home and became a doctor and went back. He's the guy in my song in the last verse, “Rick rides a motorbike through the worst slums of the city. The father and the doctor to the poorest of the poor.” Writing that part of the song, I kept breaking down. Just the thought of this guy who is dedicating his life to making other people's lives better down there is very moving. And he's so practical. He rides his motorcycle and doesn't own anything. He lives in a tiny little cubicle, but he is a shining light. He built a hospital and a school.

By the way, the headmaster of the school comes from that neighborhood. He's an amazing figure, this very tall and wonderfully educated man that rose from the streets of Cite de Soleil. So when those students go to school, they know that their headmaster is an example of what can be done.

One more question about the album. When you hear Jenny’s "Supermoon" song, with its reference to the election, it kind of puts the whole thing in the context of the Trump era. I think some people may perceive it in that light. Do you have any thoughts about that?

That song was written in the week after the election, and she wound up recounting that in her song. And then if you look at this video that we just finished of “I Found Out,” which we did in New Jersey, in Redhook, there are a lot of pictures of people on the street, and people in New York. And the key lines of the song are, "I found out it's not the love that's in your mind. It's the love that you might find that’s going to save our lives." So the inception of that song was that we were having a political discussion at this dinner one night. Paul Beaubrun was there and Jon Russell, Kathryn Everett and also Zach Niles, who runs the studio, and we were joking about opening up of a Bernie Sanders For President office in Port-au-Prince.

I mean all over the world you have these authoritarian regimes, the same kind of problems that you've had in Haiti, with an oligarchy and a moneyed ruling class that is bleeding the populace dry. A lot of these really rich people in Haiti make their money by importing imported goods from outside Haiti rather than importing infrastructure and building businesses that would serve their own economy. They're just taking.

There was a sign in Creole in one of the temples when we were making a video and I asked what the signs said. And it was "Our Own God." And that's what it is. You have to worship your own God. I think Haiti wants to be more in communication and more in relation to the outside world and not be this kind of impoverished zone only seen by NGOs and relief organizations. I used to think there was no music industry in Haiti, and that you would have to send these kids to Canada or the U.S. to teach them the skills. But no, no. I heard records were made there that were just incredible. It's actually a great place to be an engineer, and even a good place to be a filmmaker.

Some of the people who worked on our videos were part of this film called Machan Fig La, which means "the banana selling lady.” This is a movie made with all-Haitian cast, at all Haitian direction, all Haitian crew. It's about a young woman who sells bananas in the marketplace and she's got a daughter, and she is married to an artist, but he's a louse. He's philandering. In the story, he tried to marry a gallery owner, and then she finds out he's already married. It’s clearly wrong what he's doing.

Haitian people went to that movie and went crazy because they were seeing a film made entirely in Creole there in their streets, and it was a huge success. But it had a very short run because people who own the theaters were embarrassed by it. It was all about lower class people. In the end, there’s a guy who wins the woman’s heart and saves the day. She’s been treating him like a guy who just wants to woo her and she hasn’t given him respect, but in the end, she sees his true character. When she gets on his bike at the end and rides away from the lying son of a bitch that's been taking advantage of her, the audience goes nuts. It was an enormous success, but why isn't that film being seen by everyone in the country? Because the only theaters they have are owned by the wealthy, and they want to show Diehard. So it's complex.

It sure is. But you’ve made a beautiful album with a lot of great Haitian spirit. Thanks a lot for taking the time to tell all these stories.

Thank you.

Related Audio Programs