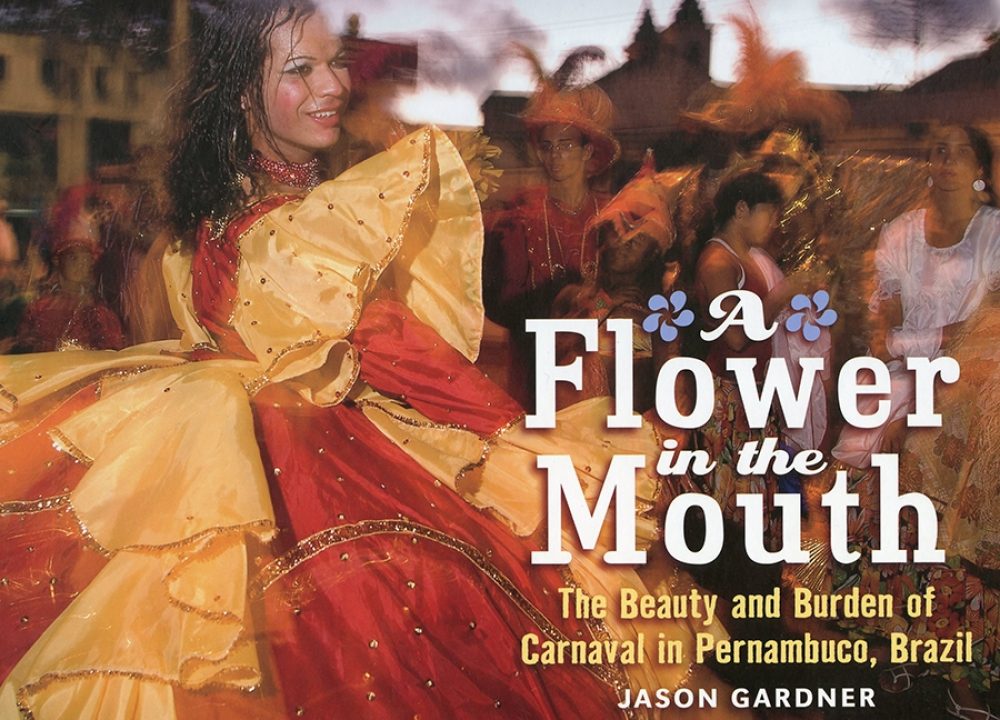

Jason Gardner is a seasoned photographer whose work has come to focus on expressions of carnival around the world. This includes major carnivals you may have heard of, but also smaller, local masquerades and rituals, literally hidden worlds full of color, vivid life and mysterious spiritual truths. Gardner cut his teeth as a live music photographer, but found his calling documenting carnival in Recife, Brazil, resulting in his 2013 book, A Flower in the Mouth, for which I was proud to write an introduction. Now, a decade on, Gardner lives in Paris and is nearing completion of a second photography book, We The Spirits, due out on Gost Press later this year. The new book is a set of intimate portraits shot in 16 different countries. I reached Gardner in Paris to talk about his work, his methods and the new project.

Banning Eyre: Jason, good to see you, via Riverside software. How long have you been in Paris?

Jason Gardner: Seven years now. I moved because my wife got a job and I said, “O.K., I’ll be up for that,” and it has opened up a whole other world.

Hence all the nordic images in this new work, right?

Well, I shot in Eastern Europe, Western Europe, some in Africa, a little bit in Guinea-Bissau is gonna be included. There’s some in the Caribbean and Louisiana from stuff before I moved. But yeah, I mean, Paris is a hub, you know? I'd say it's a great place to travel.

You've been doing photography for a long time. When I first met you, it was in the context of taking live pictures at concerts. What was the point when you realized you wanted to focus on this particular subject, carnivals and masquerades?

It is linked to music, very much so. I mean, music is my first love. My dad was a jazz musician, not professional, but he used to play sax and he used to have jazz playing throughout the house, so at an early age I could tell difference between Coleman Hawkins and John Coltrane. I started being a photographer when I traveled a lot in my 20s and backpacked around the world and took snapshots with my little point and shoot film camera.

I came back after being two years abroad and said, “Now what am I going to do?” I've always wanted to be a photographer. So let's just try that. I'm a self-taught photographer. I started my career in New York shooting music because that was my other love. Like, oh, everyone says, do what you love, right?

Still good advice I’d say.

So I started photographing musicians and I started getting bigger musicians when I started shooting for the magazine Global Rhythm.

I remember it well. I used to write for them.

Well, they started giving me assignments to shoot Manu Chao and Isaac Hayes and I shot Bob Dylan at Celebrate Brooklyn in Prospect Park. And then I got hired by Celebrate Brooklyn to shoot the whole season. I think that's where we first crossed paths.

Yes, and then we went together to Boston to shoot Farm Aid.

You were my ride. Now I'm remembering.

I had an in because Willie Nelson had heard my piece about the band Nation Beat and invited them to perform that year.

Right. Scott Kettner’s band. So how did I realize this is my thing? I started showing my work to art directors and curators in the larger photo world. They said, “This is great that you shot these famous musicians, but the photos are good because the people are famous and recognizable. I want to see you do a project of your own.”

This is in the early 2000s, about 2004. So I said, well, maybe I'll go to Brazil. I've never been there. I hear it's great music and I want to learn about it. Maybe I'll do a project there. It was really that simple. As I did my pre-trip research, I decided to do a project on traditional musicians, and I wanted to go a little bit outside the norm. I started talking with Brazilophiles like Scott and ethnomusicologists who said, “You can go to Rio, you can go to Sao Paulo, but I recommend that you go to Recife in the northeast of Brazil, because that's a very rich area but it's less known outside Brazil. And if you go, you can look up this person and you can look up that person.” And the contacts they gave me were for people like Siba and Marciel Salú, big shots now but at the time they were not.

But they were very well connected people.

So I started working with Siba and I followed his group and three or four other groups the first time. I went off-season in October 2004. And a lot of people said, “Oh, you did a few weeks of good work, but you have to come back during carnival because that's when the music's happening.” So I went back and I went back not just for carnival, but I went during the weeks before when all the preparations were happening, when it was one-tenth the crowds. Right? Because at the height of carnival, you can't do it. You can't move.

I've been there. It’s insane.

So I went back and did one carnival, and realized that I had only scratched the surface. So I went back the next year, 2006, and the next year, and after a few years I said, “Maybe I have a book.” Because every time I went back, I went deeper and deeper. I started shooting rehearsals. I had guides or culture bearers, people really hip to what was going on. And every time I came back, I brought photos. I'd make prints for people. I also did a community project to teach kids with cameras. Everyone was going into this transition from film to digital. People had small point-and-shoot film cameras. I had people in the States fund the development of the film so people could see real-time what they did. It was not a huge thing, but it was outside the educational system. It was cool.

So then people started saying to me, “Well, you have interesting stuff, but you, I think you're missing something. Come back next Saturday and I'll show you something.” And they took me deep in the favela, and I started seeing a lot of day-long ceremonies and behind the scenes preparations and rituals, stuff that when I showed people from there later, they said, “I don't know what that is. I never heard of that.” That's what led to A Flower in the Mouth.

From there, you did exhibits connected with concerts and other events. Your career started to take off.

Once the book was launched, I did a mini book tour. I went to Toronto for the Uma Nota Festival, São Paulo for the book launch in Brazil, and then also the following year at New Orleans Jazz Fest. So a couple of years later, my wife got the job in Paris and we moved. I say that very glibly now, but it was a big decision to make. But since I'm freelance, I can kind of be anywhere. When I was based in New York I had been to New Orleans, Mardi Gras, but also Cajun country in Louisiana. I went to Trinidad and Tobago, Dominican Republic, these sort of places, thinking, “Hmm, what's carnival like in other countries?”

It was largely a curiosity, both for my own knowledge and visual knowledge, to see the differences and similarities, and to explore the kind of parallels, which I definitely explored more in the second book in this project. So when I arrived in Europe, it was: Let's just continue the carnival project here. It took a while, but I made some ethnographic contacts here that kind of tipped me to some great stuff. There are a lot of carnivals in Europe that are big city commercial parties. But there's another layer, which is the small village, mountain village, small town in the middle of nowhere, carnival that is folkloric, ethnographic, a little pagan, animist, all this crazy stuff, but it's occurring in the modern age.

I see. More localized events, not in a city.

Yes. Largely in a smaller context, small to medium town. Sometimes it's so small that very few outsiders go. There's no Airbnb; there's no café; there's nothing. You just stay at their house and you eat and drink when they eat and drink.

What locations are we talking about now?

That was Slovenia, but this project is now 16 different countries.

In Brazil, you did this deep immersion, returning multiple times. What's it like when you go to an entirely new place? How do you try to approximate that level of intimacy in a much shorter time frame?

A couple of strategies. One is I do a lot of research in advance. I know what I'm looking for, and I understand what the tradition, at least on the surface, means. So I understand what to photograph and what's relevant to them and what's relevant visually. And second is I usually arrive early. And that could be four in the morning or it could be two days before. You go as early as you can to kind of be there and suss out the place and meet people. And often I have a connection with someone in the group or an outside ethnographer, someone who's working with the community,

I also collaborate, I give back the images to the folks if I can, for their promotion, for their Facebook pages, that kind of thing. It’s the least I can do.

Do you have any stories of times when you met with resistance?

I guess I met with resistance in two major cases. In one, even though it was a small village, it's very well known, and there were a lot of photographers descending down. So the resistance is, you start to become just one of the masses.

Right. You're part of a mob.

Yeah, and the second resistance is when they're getting dressed. It’s interesting photographically because there are fewer people around, right? But sometimes they say they don't want anything published of them not in costume. So I respect that. But in general, you know, it's a happy, relatively positive cultural manifestation and they're proud. And I'm proud to treat it in that respect. I shoot a lot of portraits, most of them, 99 percent are shot with film. So it's a very slow camera and what I mean by slow it's not like snap, snap. It's a medium format rangefinder so it is a manual focus, a very particular thing that happens, which basically slows everything down. It's not, “Oh come over here. Snap, snap, we're done.” But I also don't want to interrupt their ritual, their day, their celebration.

I see. I imagine that kind of process makes the subject take it a little more seriously.

It does. They respect that. There is a little bit of performative nature. They definitely give me something. But there are other photographers who make a separate appointment with them to get dressed for them. They bring in four lights with an assistant, and do a whole other thing. I tend to do very natural light and in the moment, in the field, very little location scouting if any and that kind of gets the patina of what's going on.

The images I’ve seen for the new book are pretty much exclusively portraits.

Yes. This is a different direction than Flower in the Mouth. That was more reportage, more story-based. This is more of a fine art project. It's a monograph.

I'm curious about the word “carnival.” I understand it very well in the southern hemisphere context, but I know a lot less about these European settings. Is it still a similar concept or is there something different going on in some of these places?

So I do have a subject matter expert on carnival in Europe, and he's writing about that now for the book. But, not to take too much from him, the word carnival has been sort of subsumed into this. Sometimes this is more of a masquerade and it's an ancient ritual, pre-Christian, pagan, animist. All these things mark the change of the seasons for good harvest; get rid of the bad spirits of winter and many other sort of deeply symbolic things. It can be a symbol of resistance, transgression, trance, inversion of roles. You know, all these things that happen probably have a root in Africa.

Sound right. Somewhere back there…

Not to get too deep into it, but within the carnival there are always three archetypes. There is the scary monster. There is the beautiful character, white with bells. And then there is the jokester, the trickster, the anti-establishment one, which could be either ugly or beautiful. You find these characters across all carnivals.

But in Europe and beyond, the idea of carnival is more like a season. It's a couple of months. And different masquerades and carnivals happen at different times, from basically the Day of the King, through the beginning of Lent, which is usually end of February, early March. But there's Candelaria, there's San Antonio. All these kind of intermediate holidays provide windows that allow the spirits to come at different times and manifest themselves. So by making good connections to these ethnographers and kind of paying attention to certain Facebook groups, you see when announcements happen. This year in 2023 was really the first year since COVID that it was a full carnival season. Last year, 2022, it was just coming back. And so, and because I knew this book was coming and I have two major exhibits coming in Europe, I shot probably eight or 10 carnivals in two months.

Just this year.

Yeah. And four new countries, Switzerland, Germany, and like three or four events in Spain, which I had not been to before. And then Italy. Italy was huge.

As you know, in the time since you did your Brazil book, things have been pretty tricky for non-Christian communities in Brazil. There has been heightened Christian evangelical objection to all this kind of pagan stuff, especially during the Bolsonaro regime. Have you encountered tensions between organized, mainstream religion and the practices you are documenting?

Not in the same way. The post I just did on Facebook and Instagram was about the Bottarga tradition in Spain. That is actually the inverse of that tension in that it's a colorful red and green devil with oranges and all these different icons and with bells. And they kind of run and chase the kids and they go ahead of the procession, which is the priests in robes holding the cross. So it's highly syncretic, you know. It's the sacred and the profane together, but the devil is not allowed in the church. It's all sanctioned though; it's all part of the ritual.

So is there an anti-carnival community? I'll answer that by saying not usually in the traditional communities that I visit and photograph. There is some pushback in the larger cities that have become more commercialized because you've lost the traditions, and it’s just become a drunk fest.

I see. That’s almost more about disrespecting the tradition rather than about it being a bad tradition to start with.

Well, I wouldn't say disrespecting, more just losing the tradition. People have lost what it means. So it's just a party that gets out of hand. You know, and also carnival in small villages tend to be in quite conservative communities and very sort of straight-laced. So the festival allows you to kind of blow off steam. It's a pressure valve, right? But a few people kind of take it too far, you know.

I want to ask you about a couple of the individual images. I like the ones where there's a sort of anthropomorphism, like this one where the guy is basically becoming a chicken.

That one is from Slovakia, and that's called the Kürika Hen. It's a hen that goes from house to house asking for eggs from the housewives. Eggs are symbols of renewal, rebirth, vitality. So there's a lot of this symbolism going on but I loved him. This is one of my top ones.

It's a very striking image.

What about the Basque man in a kind of fat suit. It’s called “Zakudunak with veil.”

That's another one where I just had to photograph him. These are the traditional characters of this carnival. He’s part of the whole configuration of characters. I just loved him visually, though I don't know a ton about him off the top of my head.

Would you put this guy in the category of jokester or scary monster?

It could be both.

What about the Viking-like guy in the snowy field?

Yeah, the title of that is chinelle, which is the Austrian term for the instrument that he has in his hand. It’s not a shield, it's like a cymbal. That carnival happens once every five years for a day, so it's super intense. There's a bear involved and he's kind of like the bear tamer.

Wow. If it happens only once every five years, in winter in Austria, what if there's a blizzard that day?

You have it. You have it. They're tough characters. It's in a town about an hour and a half from Innsbruck way in the mountains. And it’s quite popular. A lot of people come and their costumes are amazing. So I was lucky enough to get there early in the morning before they go into the town.

What is your timeline for this book?

I have two exhibits this year. One is at WOMAD in U.K. in the end of July. They have a theme called global carnival. I have three different sites in which I'm going to be showing the work.

Will you have physical books by then?

No. That's going to be a pre-sale situation. We are aiming for November because November 11th is the first day of the German carnival season in a town called Ulm. I'm going to be exhibiting, launching a three-month exhibit there. It's in this place called the Stadthaus, which is the main exhibition hall in this town. It's a huge space. They're going to print 40 big prints all throughout the space.

Great. Jason, I see that your Kickstarter has reached its goal. Congratulations.

Thanks. But frankly my real goal is 120 percent. The number I put in Kickstarter covers the lion's share of the cost but not everything.

So, folks, if you want to pre-order a copy, here’s the link, good until July 8. Meanwhile, one more question on an artistic and philosophical level. When you're doing a concept like this, it could be a book with a lot of writing and just a few photographs. But you put the weight of the storytelling on the images themselves.

Yes. Two or three things in that regard. One is I look at three levels of involvement for the viewer. The first level is: ooh, interesting costume, or great colors, or wow, what mask is that? And then the second level is: what does it mean? What country is that? The further you can get down the chain of significance, the more resonance and connection the person will have to the image. Then the third level of involvement is what does it mean to them, to the specific human participant in the carnival. One guy told me, “When I wear this mask, I can never die. I connect to 100 or 1,000 generations before me.” This was in Sardinia and this carnival is clearly pre-Christian, very ancient.

Another example. When I was doing the project on the Mardi Gras Indians of New Orleans—now they call them the Black Masking Indians, a different moniker… Anyway, one guy told me, “We sew everything new every year by ourselves. We're not really funded by anyone, we do it to our own money, and we don't show it until Mardi Gras Day. When I'm sewing with my family, I do it with needle and thread, and if I poke my hand with the needle, I let the blood go in the canvas. And so my soul becomes invested in this costume.”

So all these interesting stories go beyond “Oh gee, what does it mean?” in the general ethnographic sense? What does it mean to these people? That's the deeper level. So I plan to weave in these stories, but the idea of the book is to do it primarily with visuals. There will be minimal text in the book. It'll be a lot closer to a traditional monograph. The text that will be in the actual body of the book will be locations only. People always want to know where it is.

What about the kind of details and stories you just mentioned?

Those will be there, but in the back. I don't want people to be reading, to be interrupted. If they want that additional context, they have it in the back.

Well, Jason, it's a great project. We wish you luck with it.

Thank you, I appreciate it.

Click here for more on We the Spirits and to pre-order a copy.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles