The album Leave the Bones is a ground-breaking collaboration between the multigenerational Haitian roots band, Lakou Mizik, and Grammy-winning electronic musician Joseph Ray. Ray grew up and began his career in the U.K., but now lives in Los Angeles. In 2015, he took a break from his music career and made a visit to Haiti. At least, that was the plan. But Haiti had other plans for him, and now, six years later, the result is here. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached out to Ray to discuss the project. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Joseph, what you've done here is very interesting. Over the years, we have seen a lot of fusions of electronic music and roots music. As you know, it poses unique challenges.

Joseph Ray: I know that very well now.

To start, why don’t you give us a little background on your pre-Haiti career.

O.K. I have quite a varied background. My first real love was rock music and I was in a band, and then, I went to a club when I was about 16 or 17 in London, and they were playing jungle music, drum and bass—Goldie, Groove Rider, those kind of DJs. That flipped a switch in me, and after that, I kind of devoted myself to electronic music, dance music. I was in this band called NERO, we did quite heavy dub step with rock sounds.

This project came about after we did our second album. That was the kind of classic difficult second album, and I just wanted to do something different. I had a friend working in Haiti doing some charity work, and she invited me down, and I went over kind of on a whim. I didn't really have any expectations. In fact I didn't want to do an album. I was quite excited about just giving my ears a rest. But then I discovered the wonderful sounds of Haitian music, and I said, “O.K., I guess my ears will come back, and I'll see if I can do something." We were driving around and we went past this music school in Jacmel, which is a town down on the south coast. Have you been to Haiti?

I have not been there personally, but I'm familiar with the music. We have producers who have gone there and I’ve long felt connected to the place.

Jacmel is pretty nice, kind of a seaside town, beaches, a more laid-back life compared with Port-au-Prince. So I was kind of drawn there, and we came across this school called the Audio Institute, and they invited me to come by next time and do some production classes. It's an audio school where they teach young Haitian kids.

That sounds like the same school that Jackson Browne worked with. I did an interview with Jackson last year about his work there.

Yes. That's the same school. I was there at the same time and I got to meet him. He was there with a bunch of musicians, including a Malian guitarist.

That's right. Habib Koite, a good friend of ours.

Oh, yeah. He was amazing.

Jackson told me about that institution. It sounds like a great thing, providing opportunities for Haitian kids.

So Steeve Valcourt from Lakou Mizik, one of the nine members of the band, is a teacher there. And also, the director of the school is the manager of Lakou Mizik. So I was getting introduced to Haitian music, and when I met those guys, they were playing me a lot of music. They did a show at this little beach bar down the road from Jacmel. I went along and had a few rums.

As one will in Haiti.

And I got into the racine music, roots music, and I started thinking, "Well, they're taking these old spiritual songs and adding guitars and all sorts of other instruments that wouldn't traditionally be there." And of course the idea popped into my head of linking these two sounds, their music and mine. There's also a linking in the way the music is listened to. You know, if you're in a club at 3 a.m., it's in a way similar to the vodun ceremony which is a late-night thing. It goes on for five hours, and it's supposed to get people into a kind of trance-like state. Compared with an 8 p.m. rock gig, it's a different vibe. It's a long, building thing, and four hours in, you think, “O.K., I'm getting this now."

Sure.

So that was back in 2016. The very first recordings were done then. It took a while for me to learn more about the music, and to learn how I could integrate it with electronic sound in a way that was modern but respectful and organic. I think that was the biggest challenge.

I read in the press release that you had a kind of evolution in your approach to recording. At first you were thinking of setting up a beat and bringing stuff into it, but you decided that wouldn't work. Talk about that process of discovery and where you found a place where you thought you'd hit on the right formula.

I think I started with this idea that I would take electronic beats and synthesizers and sounds and then just lay vocals on top, adding in some rhythmic elements and stitching them together that way. But it just wasn't as good as it should've been. There are quite a few electronic producers who do that. They'll just take African chants and put them on top of something. And it's fine. Why not? But it's not really a collaborative project with the artists.

And then I was thinking that I didn't want to just be an engineer. I didn't want to just go in there and record the band as an album and release it. That didn't really feel like a collaborative project, and it was not what this was supposed to be. So then, O.K., how do I find that middle ground? So then there were things like I would have a string line, a background pad, and I thought I should replace that with something more authentic. I ended up using people blowing a conch shell, the lambi, which is a very old traditional Haitian instrument. I found that when I stretched it out and added a lot of reverb it became this very nice pad, and organic synth line. So we were backing lots of things with that. And then the bass sounds. I was swapping those out and putting in minuba, which is this kind of thumb piano-like instrument, although it's a little bit bassier.

Is that the one you sit on, sometimes called the marimbula?

Yes. Exactly. So, yeah, O.K., I can switch this out. The drums were almost the hardest part because for these songs, these are very complicated drum beats, which is of course part of the magic, but if I'm trying to put it into a format that's a little bit more Western dance music-focused, it could be too much. So how do I strip them back, but keep the essence? Which sounds should I use? They have this thing that's basically a rum box that they hit with a piece of metal and you get this percussive sound. It's great because it cuts through with just the right frequencies, so I would take that bit of percussion, or the ogaan, which is another kind of metal instrument.

Something like West African bells.

And then shakers. It took me a long time. It was a learning process of sound and rhythm, how to record. I was definitely learning on the job.

On one track I hear vaccines, the rara trumpets. But it sounds like you have sampled the sound so that you could play melodies with it. Have I got that right?

Yes. The main trumpet sound on that was recorded when we were out with two members of the band who were in this rara group. We were at the Port-au-Prince carnival, and we just recorded them on film to use in the videos. But they played this with on the corneille, or vaccine, as they call it. I took it back and Autotuned it. It was in the wrong key for the track. This is something that I never usually do, but you can change the pitch, just slightly move a few notes and create this slightly eerie melody, but still quite similar to the original.

It’s effective.

Then I kind of layered it with some more studio recordings of them playing the corneille. That was a fun one to do.

What was it like working with these musicians? How did they respond to the kind of things that you were doing? Did they have input or suggestions? What was the artistic collaboration process like?

I think at first they weren't quite sure where this was going, what the angle was I was going to take. I wasn't entirely sure either. I didn't know if I want to be like this or I wanted to be like that. I did a whole lot of recordings with them playing what they do. They have an accordionist in the band, and guitar and bass—like a guitar band. So I recorded that stuff, and then I realized I wanted it to be less that kind of music and more like the ceremonial music, but with added pads and electronic background.

Then as I started sending them back music, they started getting it. “O.K., we get where this is going.” And they started sending me other chants, other songs that they knew and that they could see fitting in. So for instance the song “Ogou,” which is now probably my favorite on the album, wasn't there in the start. They said this was an old traditional song that they thought would maybe work with what we were doing, and it worked really well. So, yeah, it was a long process of deciding on the sound scape. And then obviously it became difficult with travel and then COVID. We did a fair amount of file swapping.

I noticed that you really foreground the vocals. That seems to be the element of the music that is most similar to the way this music would be in Lakou’s normal performances. Of course, their vocal sound is so strong. It's wonderful. It knocks you out every time. The percussion on this album is, as you say, a little bit simplified, and held back. Sometimes it’s way back, as if it's happening in the distance somewhere. I'm thinking of the song “Nou Tout Se Moun” where the drumming is more like ambient sound. You have this passages where it's almost arhythmic. The rhythm is back there, but it's not defining the song. What was behind those kind of choices?

I was thinking if this is going to be an album and it's going to have 10 tracks, it can't be all dance bangers. And also, part of the initial learning was listening to recordings Alan Lomax made back in the ’30s. There's a song by the singer called Francilia, and she has this little shaker. And the shaker in the song ended up being used. I took a little sample.

That Alan Lomax box set is an amazing collection.

Yes. So that became one of these almost cinematic songs that gave a different atmosphere from the dance, ceremonial, traditional songs. Because there are also folk songs where it's just people walking along and singing. There are so many different sides to the music in Haiti, and I obviously couldn't showcase it all. I just took the ones that grabbed me. If I was loving a song, I just went with it. So “Nou Tout Se Moun” was this kind of female lead, sweet track. So I said, “O.K. let's make this like we’re in the countryside and somebody is just walking along singing this melody." I put it in that setting.

In one of the videos, we see the group’s elder Senba Zao. Senba essentially means "poet." It's an interesting word because it makes me wonder if there's any connection with semba from Angola which becomes samba in Brazil. It seems there are variations on that word. I don't know if they're connected, do you?

I don't.

I don't either. But the similarity got me wondering. These things can be quite tricky to sort out.

Well, he definitely explained to me the [Haitian] semba movement, which is kind of related to the Jamaican Rastafarian movement. They wanted to take it back to the countryside to a kind of communal culture. So the senba was part of that. He was a poet who could integrate songs from the past and different bits of tradition and culture and integrate it all. Senba Zao has been a senba since the ’70s I think.

I love that Lakou is a multigenerational band. I gather that was part of the concept right from the start. It's very cool they way they bridge sensibilities, and I guess that would partially explain why they were open to a project like this.

Yes. This was it. And I would say that Senba Zao was probably the most encouraging, because he said, “We've been taking these century-old songs and adding guitars and things.” He loves James Brown and Stevie Wonder and AC/DC. They were kind of into Western rock in addition to all this traditional music. So that was part of their motivation. In the beginning, I wondered, “Is this disrespectful? Is it fine to take these religious songs and put electronic drums with them?” And their response was, "Yes. We do the same thing."

That makes sense. There've been so many interesting evolutions and cross pollinations in Haitian music. What about the title, Leave the Bones? It reminds me of a great song by the Sierra Leone Refugee All Stars called "Big Fat Dog." It has this wonderful refrain, "They eat all the meat and leave the bones." It's actually a critique of politicians who take all the good stuff and leave the scraps for the people. But I think the meaning is different here.

That group has the same manager as Lakou Mizik.

Of course. Zach Niles.

I think the Haitian meaning is from a vodoun song about the spirit Elegba. The Creole says "Eat the meat and leave the bones." I probably shouldn't be interpreting. I'm just repeating what I remember Senba Zao saying: Elegba is saying, "You can do with me what you want, but leave my essence; leave the bones." He said he was singing that song during the Duvalier regime, and the kind of hidden message was you can kill us, you can kidnap us, but you won't take away our spirit.

By now, we have done a few interviews, and Steeve has talked about how you can be on this earth, you do your thing, and then you leave behind what you can. So this is one of those phrases that has so many different potential meetings and interpretations.

Let's talk about the videos, which are very powerful. How did they come together?

We felt like we were going to release this as an album with singles, we should make videos, to show people who wouldn't know anything about Haiti or Haitian culture, to set the scene a little bit and show where these songs are coming from. It didn't have to be totally direct. Actually it was a teacher at the Cine Institute Kaveh Nabatian who directed. There's the Audio Institute and the Cine Institute. It is all part of the Artists Institute, and it's on the same campus. He was down there and he agreed to shoot a load of footage at the carnival. So we went out to the Jacmel Carnival. It was him and a local Haitian guy called Wood-Jerry Gabriel, who was kind of the second camera. They went out and captured lots of footage.

There was no particular aim at the start; they were just trying to film stuff that was captivating and might enhance or set the scene for the music. With the carnival for “Ogou,” they met this father and son, and it turned out that the father was a policeman in Port-au-Prince, who traveled down there and then, when he was not on duty. He put on this amazing face paint and became this completely different character.

So this is the man who's having his face painted first white and then with all these fantastic colors.

Yes. And the third eye.

The third eye, yeah. I assume this is part of their carnival celebration in Jacmel. I've never seen anything quite like that. This video has a beautiful ritual feel that fits well with the lyrics of the song.

Yes, it's that thing of a father and son, and the son is saying, “Protect me.” Because carnival is definitely wild. There are a lot of people out there, and a lot of energy. You definitely feel alive when you are there. So it kind of fit the lyrics, this idea of going out into the crowd and the son following his brother.

The song “Lamizè Pa Dous” is talking about misery, about how life is hard. So how did you go about presenting that in the video?

We didn't want to go down that road. There's a lot of poverty in Haiti, but we didn't want to go down that side of things, so we found a local dancer, Jasmine, who was a friend of the band, and asked her to perform and if she could capture the emotion. There were lots of bits that we filmed, like kids playing hide and seek, but again, we didn't want it to be too sad. We wanted it to be sweet, with an uplifting side.

That is a challenge in a number of projects we've covered. You want to try to counteract all the negativity, the overwhelming negativity that people see about a place like Haiti, what they hear on the news. It's serious stuff, obviously, especially now. But you don't want to add to that. You want to try to counterbalance that by showing the power and beauty of the culture of the people, the art. So I understand that choice.

Yeah. That's right.

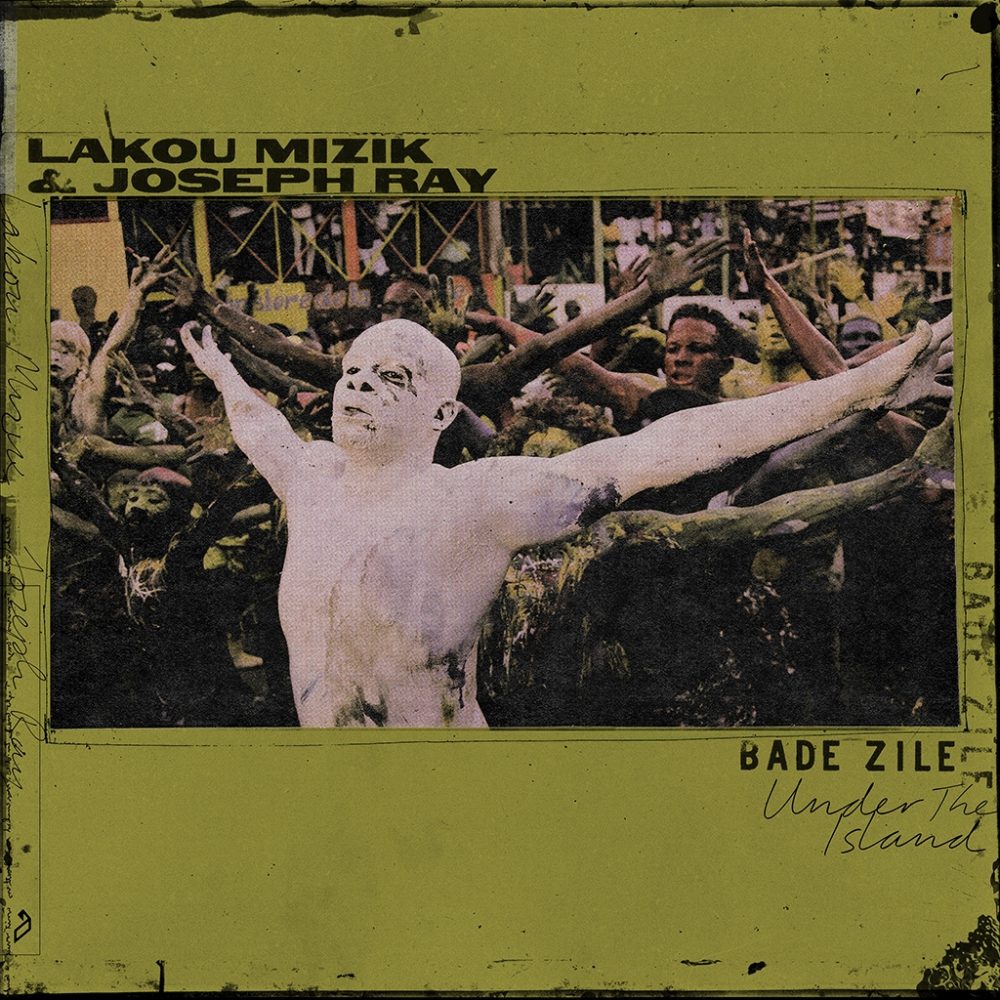

And then we have “Bade Zile,” the song that starts with Sanba Zao singing. That video features these amazing rollerskating daredevils. How did you find them?

I think that was through Wood-Jerry again. It was this crazy rollerblading crew from Port-au-Prince, who started at the top of the hill and wound their way down with the daredevil cameramen on the back of a moto, filming them. And then down in the square, they were jumping over other motorbikes. Super fun.

That song is also a spiritual. There are lots of spirits mentioned in the song. There's no particular link to the imagery. The song title means “the island under the sea” as far as I know, but there's not too much meaning to the lyrics. So we were like, “Let's just do something fun that captures the music.”

Did you film these things specifically with the song in mind, or did you just come back a lot of video and figure out how to piece it together?

I think we did have ideas and then thought maybe we should do different things. “Ogou” is basically a carnival song, and the way that it came out, it's got a very sweet melody to it.

Yes. It is a bit gentler that the others.

Yeah. And then we put it on top of the carnival footage, and strangely this worked great. We weren't expecting that.

It is interesting, because I watched the video first, and then when I was listening to the album, the song came along, and I was struck by that sort of gentleness and the kind of easy lope of the rhythm. It's not as driving is some of the other songs. And then I realized that this was the song that went with all that crazy carnival stuff. I went back and watched again, and I saw what you mean. It's a kind of a paradoxical fit.

Sometimes you can be too literal with things. You can think, "Oh, this is about this, so let's film this." With “Bade Zile,” you might think this is about an island under the sea, so try to go that way. But then you think, “This isn't anything at all. It's pointless. Let's get some rollerbladers!”

The album was just finished this year, so you were having to work through the COVID period, working remotely. What was that like?

At that stage it was mainly finishing touches. Obviously, a release can take quite awhile between the project being finished and the actual release. And of course it was interesting to find the right label for it. I'm really happy that we went with the label we have, Anjunadeep, who I personally have released with before. It’s a dance label, straight-up house music. They've done a few projects with bands, with a Nigerian band recently I think. This was a little bit out of their wheelhouse, but I thought it was fun. I wanted this project to be alive, and to reach an audience that might not expect it, and I think they've done a great job of supporting it, and most of their fans would probably have no idea about Haitian music or culture, but hopefully they will be open to it.

Well, it is a unique project, and your timing was good. Haiti would be a very tough place to work today.

I don't think we'd be able to do this now, between COVID and what's going on there politically. I managed to go there three or four times. I spent about six months there total, and I certainly enjoyed the time. It's sad to see what's happening.

Sure is. Anything else you'd like to add?

I guess there's one thing that I thought about since doing it. It's really something to see people dance to these tracks in clubs and venues in places like Miami or Chicago or in Europe. We did one for a Berlin-based dance music record label. They put on a show there. It's cool to think about these super old songs playing there. People won't have a clue what the lyrics are or where it's from, and that doesn't matter. They’re just enjoying the music and dancing to it after all these years.

I'm sure that is satisfying. Thanks for talking with us, and be sure to check out that song "Big Fat Dog." You will get a kick out of it.

Nice one.