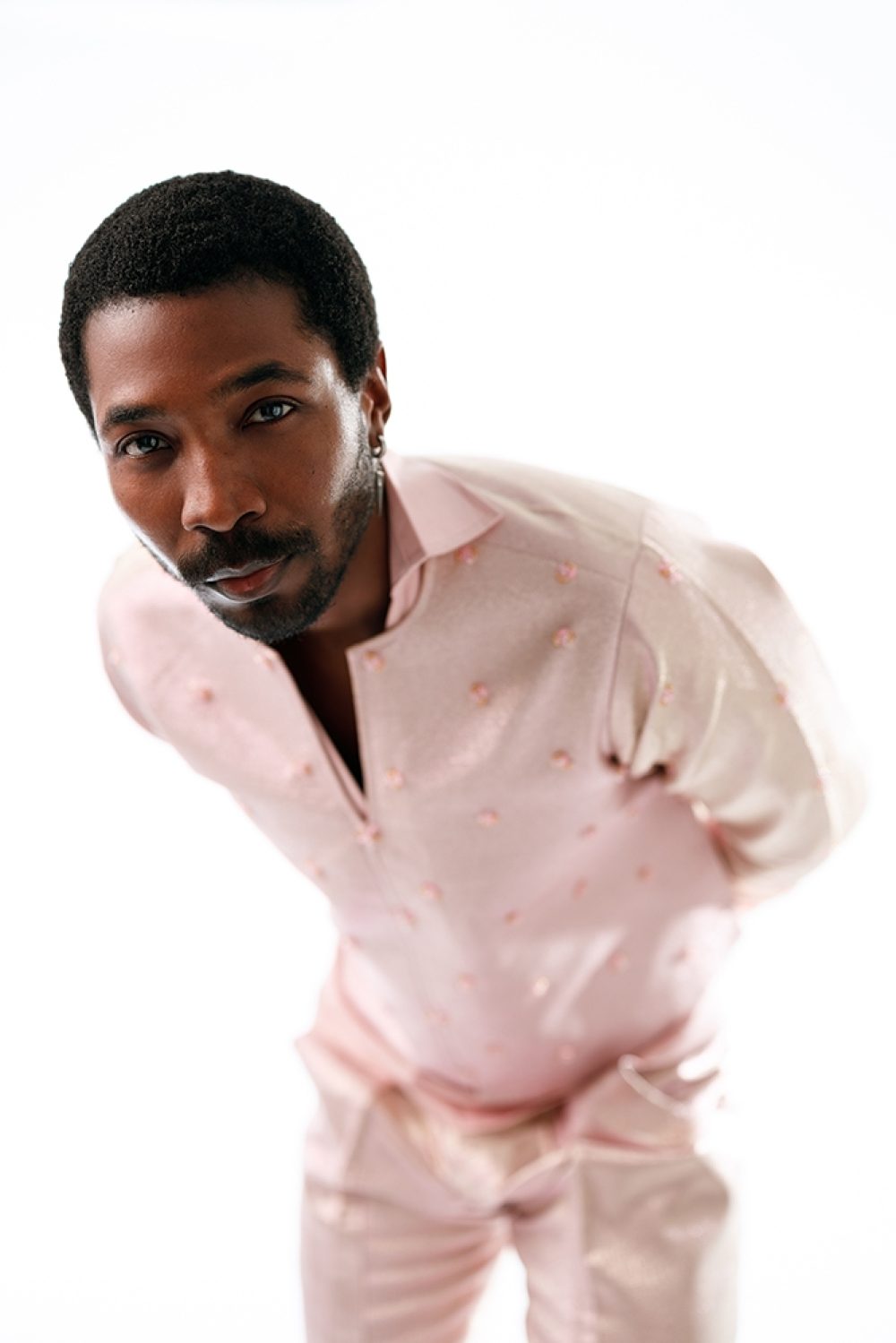

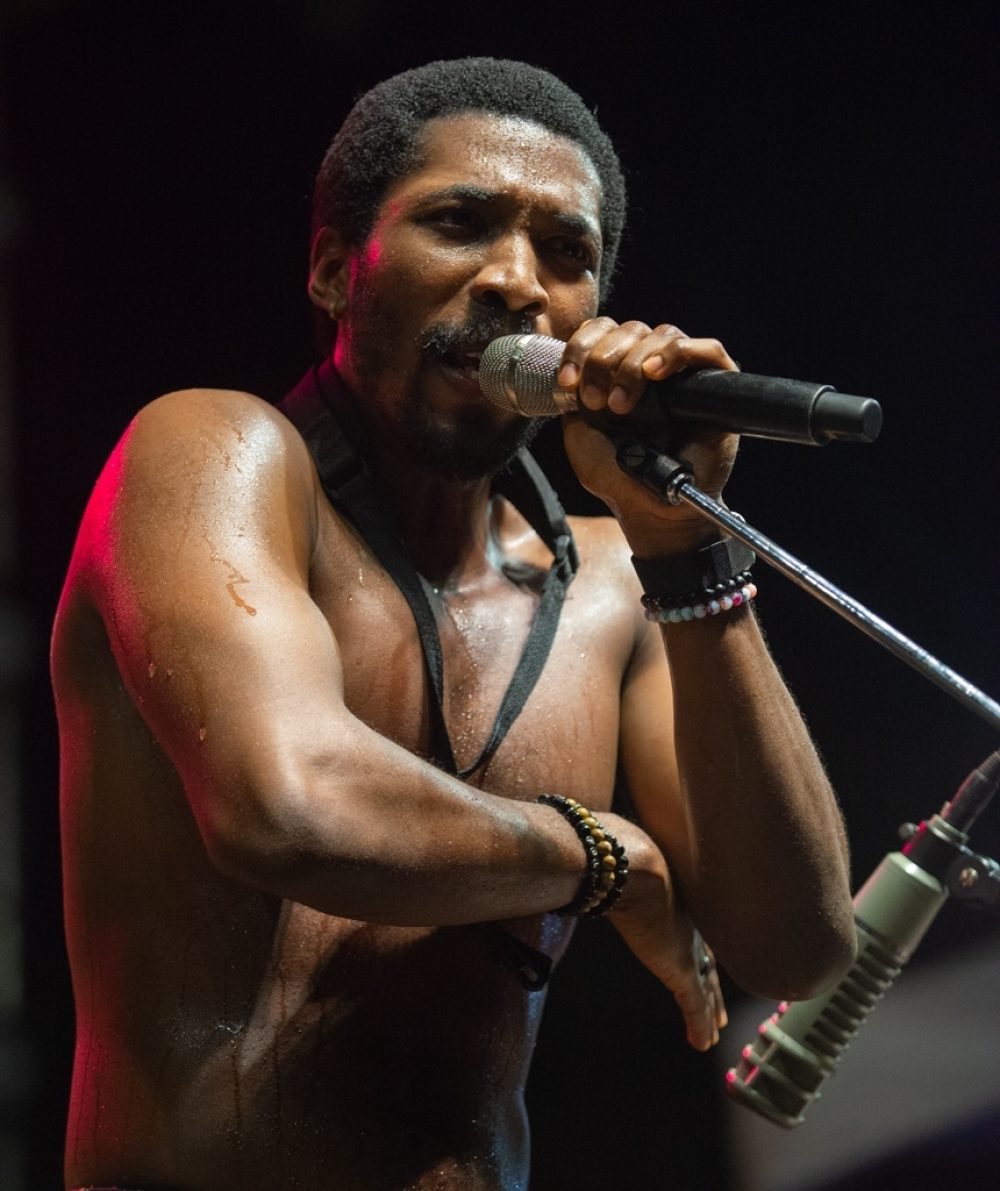

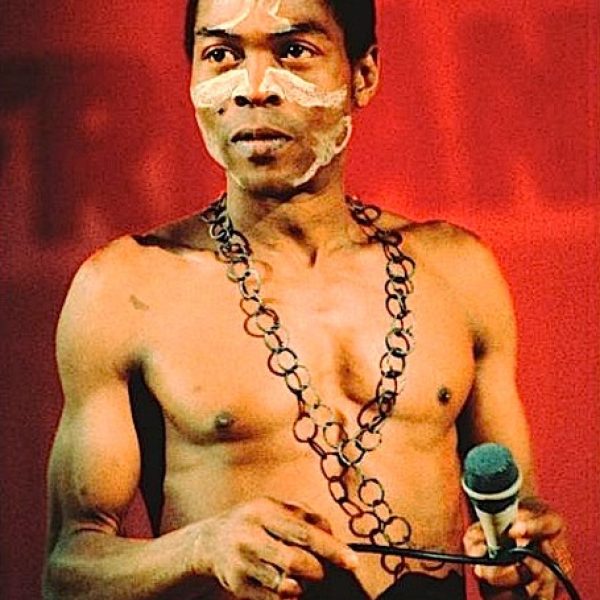

Madé Kuti, son of Femi, grandson of Fela, is carrying on the family’s Afrobeat tradition with distinction and originality. For his debut 2022 album Forward (which we discussed at the time), Madé played all the instruments, an impressive feat, but one not reproducible on stage. So now, he has developed a band, The Movement, which we caught live at the 2024 Sauti Za Busara Festival in Zanzibar. That show was impressive, but better still is the band’s debut album, Where Does Happiness Come From? Chapter One (out July 25 on Legacyplus Records) is a landmark release. Nothing short of a tour-de-force these 13 tracks mard the most progressive and innovative 21st century take on Afrobeat yet to appear. Throughout, we get sharp arranging, surprising and inventive rhythms, trenchant lyrics full of highs and lows, and dense soundscapes that call for many, many listenings. I reached Madé over Zoom in Lagos to discuss this remarkable album, and he had plenty to say!

Banning Eyre: Hey Madé, am I finding you in Lagos?

Madé Kuti: Just on the outskirts, about five minutes out.

On a good traffic day, right?

That’s it.

We spoke a few years ago, when you were about to go on tour with your father. That show was great by the way.

Nice.

I was also in Zanzibar when you played at Sauti Za Busara, also wonderful. It’s funny. We were there with listeners to our national radio program Afropop Worldwide. We had just finished eating in one of those seaside restaurants. Everyone had left, and I was sitting there with one of the guides, and you sat down right in front of us. And I thought, “Oh, I recognize that guy. Who the hell is that?” It was only when I saw you on stage that I tweaked. “That was Madé!” Anyway, that was a great show.

It was a great experience.

So I've been listening to this album. It's really impressive. The energy is just overwhelming. We played a track from it on our most recent podcast.

That’s cool. What track did you use?

We use the opening track. “Take it All in Before the Lights Go Out.” It has a resonance for us because we had just lost our government funding that we've had for the past 38 years, thanks to the new regime here. So a bit of an inside joke. But let’s talk about the album overall. I know you played all the instruments on your first album, which was quite an achievement. How did you go about making this one, now that you have a band?

Yes. Well, as the first album was released, I wanted to perform a lot of those numbers live. So I put my band together, and we're about three years old now. I call them The Movement. Funny thing was, I couldn't perform about half the numbers I recorded by myself. It just didn't deliver the kind of results that I initially intended for the album. So I just started writing music for live performance. And that's what resulted in this album. So these are really songs we've played for quite some time. A few of them are about a year or two old.

So this is a band album.

Yes. It’s more or less what we would hear if you heard it live. Same performers.

You play a number of instruments, I know. Tell me the instruments you play on this album.

On this one, I played trumpet. I played alto sax, and I think I played tenor as well. And then I played piano. And vocals, of course.

The album has a very distinctive sonic kind of quality. There's so much happening. I love the way the horns work with the piano. It's a unique sound you've created. I really do feel like you are delivering on the idea of taking Afrobeat to a new place. The music is clearly in the tradition, but also very distintive. I’m curious to know what kinds of music you like to listen to that are not Afrobeat at all? What are some of the other things that you bring to the mix because of your personal experience?

I think, other than the sort of staple genres that are very well within the frame of Afrobeat, like jazz and African traditional music, highlilfe and genres like that, I branched out in my teens, and I started listening to a lot of classical music because I wanted to study at Trinity, in London. So I studied classical piano intensively, without any other instrument, just piano for about four years. I did the ATCM diploma exam at Trinity, and I got a pass for that one, which was a very nice accomplishment. But I think what influences me slightly more than that even is indie rock.

Indie rock! That's interesting. I hear that, and was going to ask you about that. You’ve confirmed my impression. I hear it in the way you write and deliver lyrics.

Yeah, I think lyrically, and sometimes musically as well. I'm definitely influenced by it. I think one of the first bands I had heard when I was a lot younger, probably in my mid-teens. might have been the Arctic Monkeys, which I thought were very interesting at the time. I heard them on the late show that my dad was on, that UK TV show with Jules Holland. So I was watching my dad perform. And then I just decided to turn it on another day, and I introduced myself to all these bands. Then I just tunneled, dug deep into that, and then I even got as far as Japanese rock, which I started to enjoy a lot.

Interesting.

So that's something that I'm quite sure my grandfather and father didn't listen to.

Probably not. But you know, what you're demonstrating is just how adaptable this genre is.

Exactly. Yeah.

I mean, I can hear clearly the difference between your father's music and Sean’s music, for example. There are stylistic markers there, but you've made your own markers, and that’s cool. So tell me about the band. How big is it? Is it another huge Afrobeat band?

I think there are about 15 of us. We have four horns, two trumpets, one tenor sax, and one baritone sax, a rhythm section with drums, percussion, bass, guitar, and keyboard, three female dancers and backup vocalists, and then one male dance artist, who is fantastic live.

Wow!

He contributes to the performance as opposed to the music. So, yeah, touring is very difficult. You know, tickets are expensive, but at least around Lagos and in The Shrine we have very nice performances, because it's such an organic band.

A lot of us have been together since the beginning. I think only two members have changed. The guitarist who recorded on this album has actually moved to the States. And we have a new guitarist. But that's about it. Just one person. Everyone else is still there.

That's great. Well, I'm gonna have to get back to Lagos and see you guys in The Shrine.

Yeah. It will be lovely to host you.

We were there in 2017. We spent a month in Nigeria doing all kinds of cool research.

Not long ago.

I agree, but someone I met from there recently told me, ”Oh, you wouldn't even recognize it.”

If anything, it has just gotten more expensive.

Ow. Sorry.

Let me ask about the drumming on this album. I find the rhythms really interesting, very sophisticated. I notice these days that drummers in so many genres are playing like Tony Allen. You can hear his mark in a lot of recordings. But the stuff your drummer is playing is beyond. Such cool, complex rhythms.

With the band, almost every single thing is written for the musicians. I write before I share with the band. I notate my music, especially the drum parts. I start with the drum parts, with drum and bass most of the time, because that sort of determines the texture and structure I want to work with. So with tracks like, “I Won't Run Away,” I knew I wanted it to be in an irregular time signature, and I didn't want the regular pop genre-esque 5/4 time. So I thought if I were to tweak it to make it sound a bit more Afrobeat, how would I do that? So I spent a bit of time with just the drums. And then I think it turned out to be [sings rhythm].

So I always work on the drums first, and then I share with the band, and he is a fantastic drummer. He's very patient with me, and especially when I want to try certain things, inventing patterns. And he then embellishes it in a very organic and natural way for the recording and live shows. He's very good at that. He performs them exquisitely.

I think, even with a lot of Fela’s tunes, like in the early ‘70s and all the ‘80s tracks, he did the patterns himself as well, like “Teacher.” I know “Zombie” was him as well. That’s Fela’s drum pattern. But the “Wait and See” track on the album, I used Fela’s “Pansa Pansa” beat. I just slowed it down from Fela's version. That’s the “Wait and See” drum pattern.

What’s the name of your drummer?

His name is Emmanuel Idowu. He’s coming with me to Italy this week as well. We're doing a very short gig with a brass ensemble for the Solomeo Festival.

Nice. I know that Seun is touring now with a much smaller band. Have you had to trim down for international tours?

I haven't had to yet, but I imagine that I will very soon. So far, wherever I've been for shows they've been singular events. I've never gone for a long tour. So if I'm going to be on the road for four months, I know it's so expensive. I realize that, because it's Lagos as well, tickets are ridiculous. Some of us have figured out that it's cheaper to fly to Abuja and buy a ticket from Abuja than it is to fly out of Lagos directly. Every time I fly, the planes are full, regardless of how expensive the tickets are. So it's working for the companies. And yeah, that’s the major deterrent. It's really the cost of tickets. Being on the road with many people isn't too much of a problem, but it's the upkeep. So it's the amount of hotel rooms, the amount of local travel as well. That's that's makes it now almost impossible. I mean the only person I know that still does it is my dad.

Right. He’s coming our way this summer. We’ll see him in Montreal at the Nuits D’Afrique Festival. You didn’t mention the cost of visas, but that’s also gotten ridiculous. Just so you know, this is one of the things we are focusing on at Afropop right now, trying to help people who are brave enough to tour here. For you, we’ll start with this interview. But as soon as you guys have possibilities to play here, we'll be there with you every step of the way.

Amazing. Thank you.

We’ve recently added some social media folks who are younger and sharper at that than me.

Yeah, that is my probably my weakest point today, social media and managing all of that.

It is surprisingly demanding to do well. Let’s get into some of the songs and messages on the album. I feel like your messages are a little more upbeat and hopeful than a lot of Afrobeat tunes. Maybe it’s a function of the circumstances in which you grew up. I know things are still pretty dicey in Nigeria, but you’ve come up with the security of the Kuti family. Maybe that’s part of it. “I Won’t Run Away” is an incredible piece. There even a kind of manic ecstasy in it. We can get into that one more, but just in general, where are you coming from message-wise?

I think my direction lyrically is very heavily influenced by the direction that my father and Fela took. Growing up at The Shrine was very political, and I've learned from my father. You know he would perform his songs a lot before he'd record them. So if you were at The Shrine, you'd see the sort of real-time reaction to songs that are facing and tackling issues happening at that present moment, before the recording and release. Something would happen in the papers, and my dad would write about it, and then we'd hear the song next week, and that sort of direct approach towards the issues was very, very clear at the time. I feel that was appropriate for that era, because I think that Nigeria at that time was still a bit fresh out of independence and democratic rule. We had so many republics through military regimes and democratic ones. And so it was ideal for an artist to tackle people in power and the government and the elite.

But now, after so many decades--and my dad is 63--I find that the average Nigerian has sort of succumbed to a narrative. It’s a narrative that sort of releases them from any responsibility for their own predicament. Because of that, they are complacent in their situation, without realizing just how much power they wield, and how powerful the collective can be if they decide to move with one mind and one goal. So I thought my music should be as reactive to what I think is the immediate problem, as my dad and Fela did at that time.

The immediate problem to me right now is individuality, and it has a lot to do with miseducation. The curriculum in Nigeria is very academic; you learn nothing about history. You learn nothing about cultural significance. It’s so much about academic subjects like maths and English and exams and testing. The goal of education is eventually to leave the country and get higher education out of the country. Nothing really teaches you about things of substance, values and worth.

Something I found really interesting is that we don't even learn anything about pre-colonial history. I had to do a lot of research. Lots of the things I learned about Africa I had to do through self-study, and for my uncle it’s the same, and for my dad it’s the same. So it's hard to relate these things to people who have gone through that very strict system of Western education and say, “Hold on! It's not necessarily the way that America does things and the United Kingdom does things that will apply to Lagos and Nigeria. Our culture is different. The way we act with one another is different, and we are applying systems that don't work for us, and that haven't worked for us.”

Borrowed ideas.

Yes. They're borrowed. Exactly. So my songs want people to discover themselves, first on an individual level, where they take accountability for their character. I think it starts from the little things. What kind of person are you? Are you someone who reflects on your weaknesses? Do you accept your wrongdoings, and do you try to learn from them and then grow from them? If you try to better yourself on a daily basis, then from that moment, you can sort of distance yourself from this corrupt regime. Otherwise, you're not too different from these people that you are constantly fighting against. But once you do that, then you find like-minded people who share that school of thought. That, I think, is the only way I can see any hope of Nigeria being progressive. First, you reflect on the individual, and then the community, and then you look towards the larger scheme of society.

So my songs are very direct. “I Won't Run Away” is about not running away from the things that you lack on a personal level. It is your weaknesses. Is it lust? Is it greed? Is it anger? I discovered mine at the time was anger, because I used to get so upset. There was that sort of line where I'd lose my temper. It would be so hard for anybody to calm me down. My dad used to really scold me because of it, and I thought: at what point do I take responsibility for my temper?

This was many years ago, and I just started working on it. I also started working on how I related to certain people that I didn't agree with. I think that has made me a much better person for my family, and for my siblings that are younger than me. They can now rely on me more. My father can rely on me more. I can take a more responsible role within the family, and then I can go out into society and contribute positively. So that's what the album is really about. Where does happiness come from?

A great title, by the way.

So it’s within you first, and then you project it out.

That's very interesting, because you definitely don't come across as angry here. So where does happiness come? I was just reading a book about humanities, and there's this four-line bit of wisdom from the past, something like: Happiness is the only good. The time to be happy is now; the place to be happy is here; and the way to be happy is to make others happy.

There you go. Just like that.

The timeless wisdom of humanists.

I love that.

Yeah, it's beautiful. But you're talking about the complacency. Inevitably, we're following a lot of these big Afrobeat stars. At the moment, I'm sensing a certain fatigue with the formulas there. Some of the people I know who really listen to a lot of that music say it's feeling a little stuck now. You don’t have to comment on that. But regarding complacency, one thing we've always noticed is how fundamentally apolitical it is. It’s always been a bit ironic that chose a genre name that nods to Fela when there’s so little edge to the messages. We've probably talked about this before. It's becoming a bit of tired subject, the whole Afrobeat vs. Afrobeats phenomenon. At this point, it is what it is.

But I'm curious about how you and your sound and music are penetrating, or not penetrating, that mainstream Nigerian audience. Do you feel like you are getting those listeners? I know that traditional Afrobeat is still a strong subculture in Lagos. And I know that Seun and your father have had interactions with some of these big stars. I don't sense hostility, but there's a very different sensibility there. How do you see yourself and what you're doing in that context of this massive mainstream success for the likes of Burna Boy and Tems?

Yeah. So I remember the bloom and the scale of what was exploding with Afrobeats. People used to ask me similar questions like, “Oh, but is it Afrobeat?” At a point, I decided that trying to spend a lot of time making clear the differences between genres would be too exhausting for me. So I started nodding my head. Yeah, they're Afrobeats musicians, but I think what they do is fantastic in the sense that they have found a way to commercialize their genre of music. It's not too similar to Afrobeat music, but it’s something that is very easy to listen to, and represents African rhythm in a way that I like. It's not hip-hop. It's really authentically West African, though now there's Amapiano, which is South African, in it as well.

But to your question, when I started it was almost entirely poor, the sort of reception initially around Nigeria, say, within the first few months. But after the first few shows that I hosted at The Shrine, it was really good, but good within a sort of controlled community. So when we had gigs at The Shrine, we'd get about about a thousand people. And every time we had shows outside and around The Shrine, they always went fantastically well. I did one recently at a small beautiful venue, and I think we had about 250 to 300 people, and it was a fantastic show, but not the sort of capacity that I would imagine if one of these Afrobeats stars played the same venue. It would probably be around 500, maybe 700. But I think I cannot expect people to so easily shift towards something that they are not regularly exposed to.

Right.

So The Shrine, the government, and the powers that be at the time of the building of The Shrine were very intelligent with how they did it. This was before social media, before we could defend ourselves publicly. The press wrote about The Shrine, making it a very unreligious place. They would say, “It's not Christian to go there,” and we are devil worshippers and things like that, because of the name. So they did that. And then they went with the sort of danger narrative as well. “It's dangerous. If you go there, you might not make it back out.” So it's taken a lot of work the past decade for the family to clean out all of that and slowly get people's minds back on track about what The Shrine really is about.

You’d be surprised that the people who live around The Shrine have never been inside, and the day they go inside, it's always the same thing. “I didn't know it was like this. This is not what I heard. This is so fantastic! I'll see you again next week.” It’s always the same first impression. And that's what we're fighting against. It's a narrative that has had a very strong impact over the past few decades. When my dad had his hit tracks like “Bang! Bang! Bang!” and “Sorry Africa,” his music was banned on radio. You couldn't listen to him. This was before streaming, and you couldn't sell CDs. The only way you'd hear him, you'd have to come to The Shrine, and they made The Shrine a bad place, so there wasn't any real avenue for people to expose themselves to my father's music.

So now we do our best to be as out there as possible. We have shows in and out of The Shrine. My dad still plays weekly, every Sunday. He still gets about a minimum of 400 to 500 people, and it changes every week. And honestly, I think it's cool. I think it's nice that there are still people who want to be challenged with what they listen to. They want to hear something fresh. They're okay with being introduced to something that's not quite their thing, but they want to see where it takes them. There are still people like that here, and hopefully, the numbers increase.

So you've got your constituency. It's not mainstream, but it’s healthy.

Yeah, exactly.

Does your music get radio play?

As of right now, I'm getting a bit. Some of them you have to pay for in Lagos, for various reasons, and we've made some payments here. But because of the steadfastness of my dad, and also my mom, I've been getting some favors called in as well. So yeah, we're on Niger FM; we're there quite a bit, and a few others.

Are they playing this new album?

Just the ones that have been released so far, “I Won't Run Away” and “Life as We Know It.”

Well, they’re in for a surprise when they hear all the tracks.

Do you have a favorite?

I think it's gotta be “I Won't Run Away.” It’s really a masterpiece. I also love the opening track, “Take it All in Before the Lights Go Out.” The energy there is just killer. When we played on the podcast, our co-host in Malawi went nuts. She said, as soon as she heard that, she couldn’t stop dancing all around her kitchen.

Amazing.

Let me ask about that first track, “Take it All in Before the Lights Go Out.”

For that one, I started writing the horn section, and it just kept developing. And I just thought, I don't think anything should take away from this brass. It’s a brass track. So that's the direction I went with. And the first few times I rehearsed it with my band, they weren't happy, because it's long and heavy and loud. But now it's one of our favorites to perform live. So I’m happy with how it turned out.

So the title just expresses that emotion. Get it while you can.

Yeah, take it all in here. And I put my wife at the beginning as the voice, which we don't do live. But that’s her speaking on the album.

What about “Pray”? That's another one with really interesting drum part.

Yeah, I had a lot of fun with that. That drum part came with working out the bass line. I think the bass line came first for that one. [Sings] And “Pray” is about what I said earlier, about the individual, but at the same time carrying a message of hope, because I want to have kids, and I hate to think that Nigeria is done for, and we're going to keep heading backwards and getting worse. I don’t want to think that survival will be impossible in the next two decades. So I want to place my faith in hope that things will get better. And you know, I try to play my part as a musician who carries a message that can inspire as opposed to, you know, distract people. That's what “Pray” is really about.

That hopefulness comes through, and this is why I find your work more upbeat emotionally, more optimistic than a lot of Afrobeat classics. Let’s talk about “Life as We Know It.” You have this line in there warning “Mr. Social Drinker.”

I wrote that song very funnily in the car on my way somewhere with my wife. Well, she was my girlfriend at the time, and now my wife. I was thinking about life's excesses, and I just thought it's so funny how easy it is to lose yourself in things like addiction. My favorite line there is... There's something called “short-time joints” in Nigeria, where it's like you meet an escort for a very short period of time. So it doesn't last long. It’s quite commonplace that businessmen and people that are quite middle class go there. And I say to my friend, “Pray that one day it's not the short time joint that you visit, and you see your daughter.” And it goes on like that. How many cars do you need?

You know, there's a serious drug epidemic here as well, and I find that weed is probably the healthiest drug that Nigerians are taking. Natural weed is the best thing they're having right now, because now there's so much cocaine, there's a lot of crack. There's a lot of fentanyl, and so you see people on the streets just frozen sometimes. And when you argue with people about drugs, they have all this defense, claiming that the drugs are making them intelligent. That leaves you in the gutters. That's what the lyrics say. So it's making fun of things like the escort thing, and how many cars do you need to drive from one place to another, but also mentioning things that I think are incredibly terrifying. Because this drug problem right now is scary. And it is so commonplace now. So that’s “Life as You Know It.”

Yeah. Still illegal. Yeah.

It's amazing how much that has changed around the world since your grandfather’s time.

But not in Nigeria yet. Unfortunately. I mean, I don't smoke, but I really don't think weed should be illegal.

Let's talk about “Oya.” This one has a tougher feel to it.

Yeah, that was about the End SARS protests. In 2020, there was a massacre at Lekki, where the army killed all those people who were protesting, and they covered it up by saying it never happened. Until today. There's still no accountability or court case covering it, or any real seriousness for who gave the order. And this was just some people wanting to be hopeful about something, and fighting for it. And now, look, she's dead because of our incompetence. Black bodies all over. And then at the end it calls for something more, because what happened afterwards, even though SARS was disbanded, that force was put away, unfortunately nothing else really came about from it. There's still a lot of brutality, and no justice for the people who were killed that day. So “Oya” is about that. Oya means to do something, like “Let's go.”

So SARS, the specific force that was responsible for so many killings, has been disbanded but nothing has really changed.

I remember something very funny. I once went to a police station to bail a friend out, and I saw a man in a SARS uniform. Then on the day of the protest, I saw the same man in a police uniform. So the force itself has been removed. But I have no faith that they fired all those people. I'm sure they're still within the police.

Just change the uniform. Well, as you probably are aware, we're becoming familiar with this kind of thing in this country, masked men out of uniform grabbing people off the streets. It’s really shocking. I just never thought we would come to this. It’s giving us a new sense of vulnerability, boy. Kind of scary. But hey, life as we know it, right?

Life as we know it.

Well, is there anything else you want to say, as we introduce people to this album.

I think maybe people should not be too compelled, or should not let themselves base their interest on the lyrics, and what the album is about, or what I perceive it to be about. A lot of it is intentionally direct, but also a bit vague. A lot of times, I don't specifically talk about what the issue is for the individual, because it's supposed to be personal. Everybody is supposed to find who they are through those tracks, and what it is they want to reflect on, and what they want to improve and what they are searching for, and things like that. So Where Does Happiness Come From? Chapter One is not about me. It's supposed to be about everybody.

So, Chapter One. I imagine you're already working on. Chapter Two, right?

Yes, we are, and this is because the first album was called Forward. So I just thought, if that is the forward, then this is Chapter One. So yeah, I'm quite sure I'm going to maintain this chronological structure.

Well, wonderful man. It's great to talk with you again, and good luck in Italy. America is waiting for Made Kuti and The Movement.

Thank you.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles