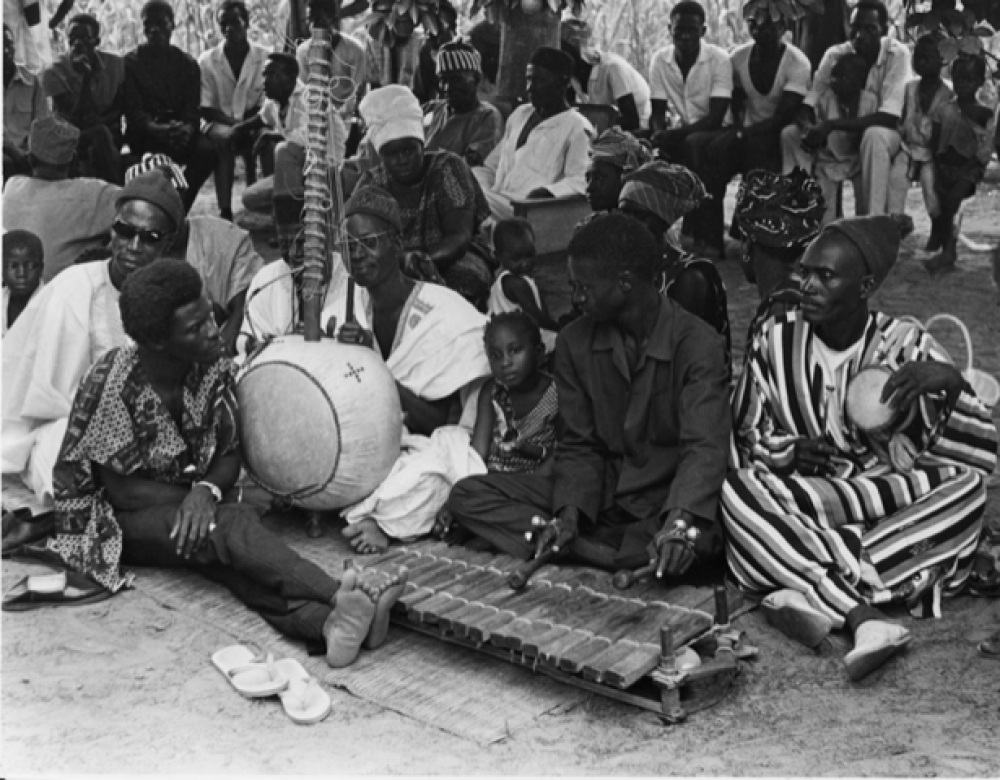

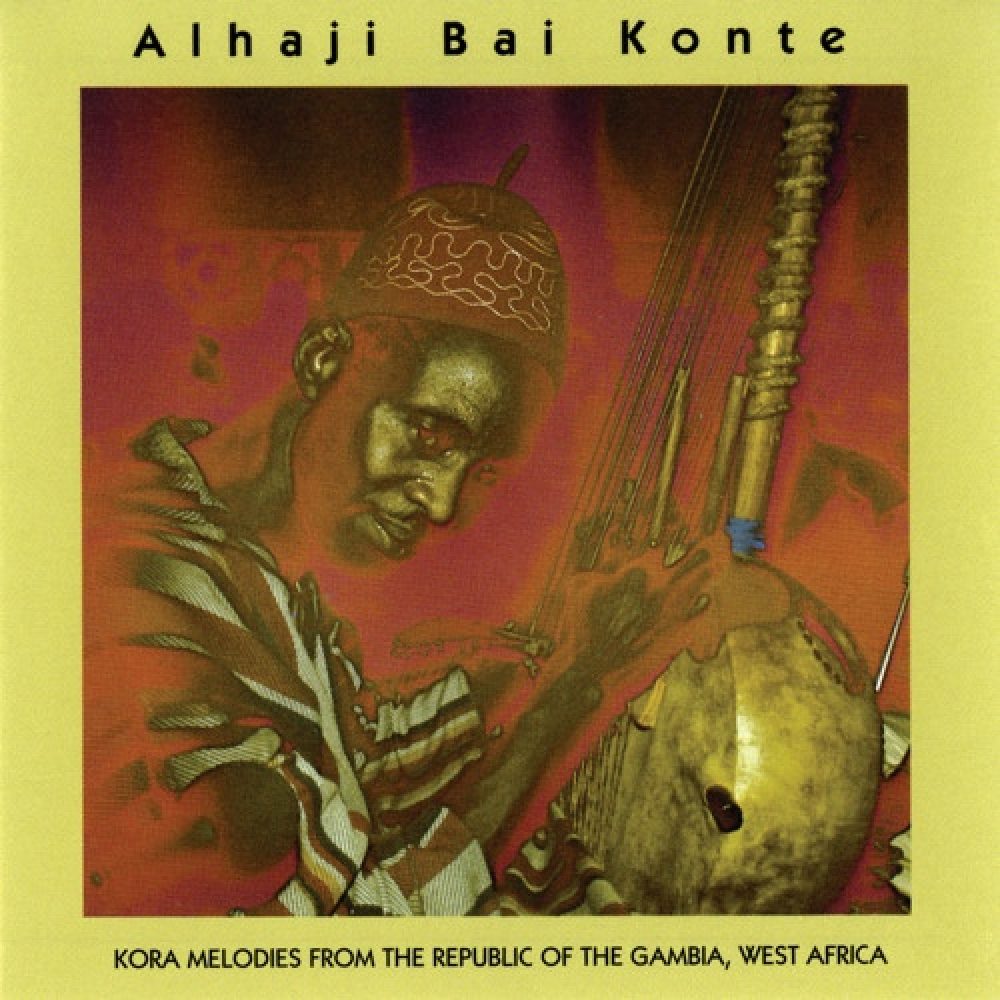

Fresh out of college in 1971, Marc Pevar and his wife Susan traveled to the Gambia where they lived for a year in Brikama in the compound of master kora musician Alhaji Bai Konte. Marc had only recently discovered kora music, and his decision to study with Bai Konte was initially something of a whim. But it resulted in one of the first commercial album releases of kora music in the U.S., Kora Melodies from the Republic of the Gambia (Rounder Records), as well as memorable concerts and a film project narrated by Taj Mahal. Banner and thumbnail images for this feature by Marc Pevar.

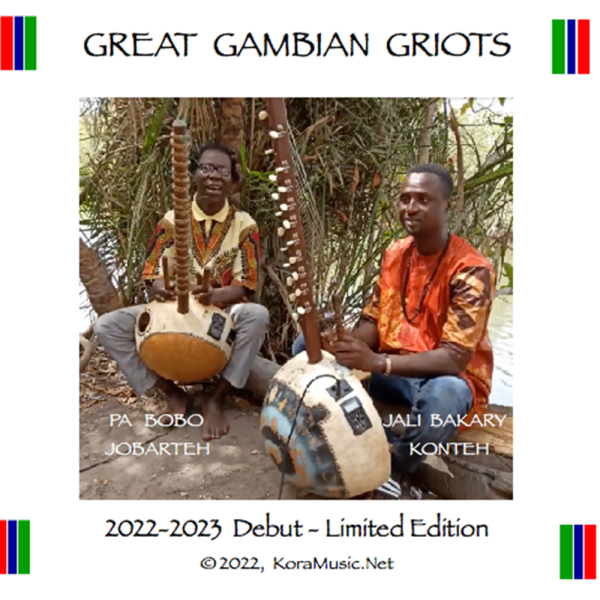

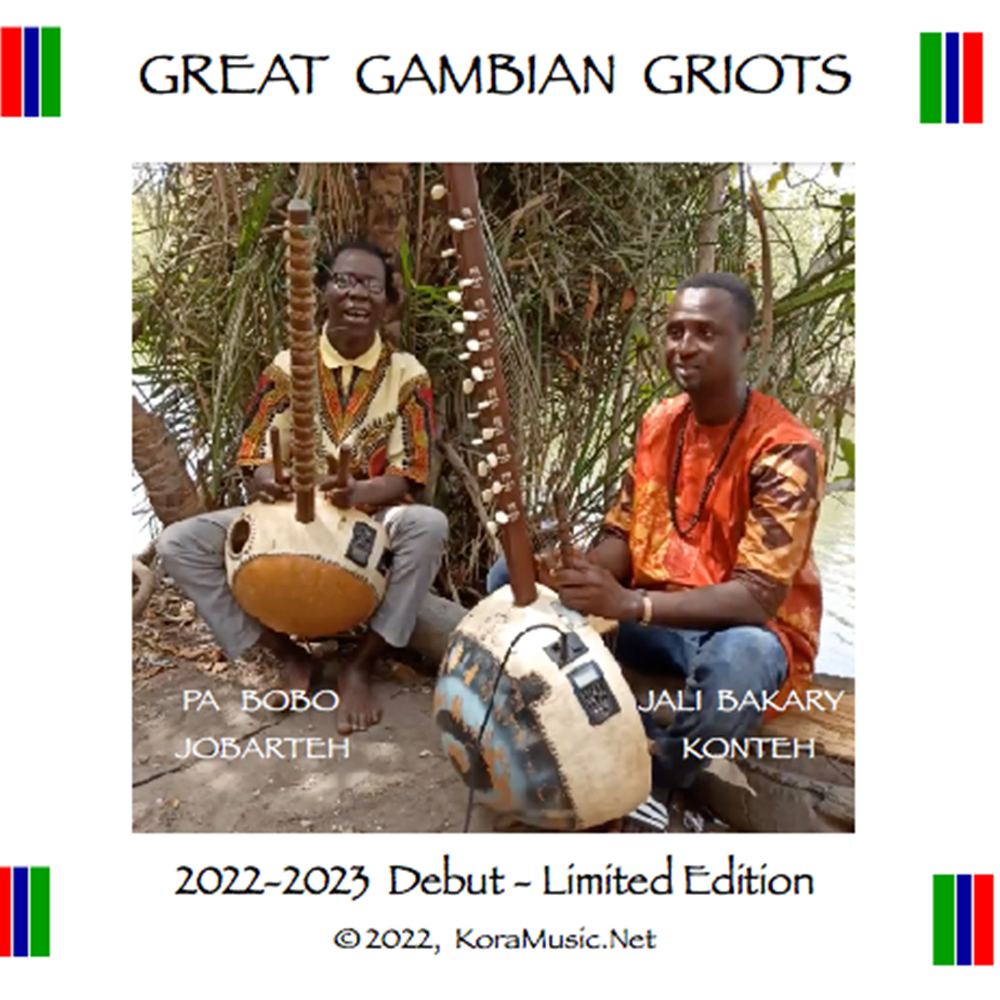

In recent years, Pevar has revisited his passion for kora music, arranging concerts and other events for some of Bai Konte’s kora-playing grandsons. The project is called Great Gambian Griots. In 2019, Banning Eyre sat down for a lengthy interview with the Pevars. What follows is edited excerpts from that interview, interspersed with comments from interviews with Mande music scholar Lucy Durán and U.S.-based Malian kora player Sirifo Sissoko, the brother of Ballaké Sissoko.

Marc Pevar: I was never thinking of getting professionally involved in the music world. The first kora music I heard was a very low fidelity, poorly made cassette. It was not a commercial recording. Susan's father had bought the instrument in Senegal, and asked the musician to play a little bit so he could hear a the music to go with the instrument. That's all I had heard.

What I recall is arriving at the compound in Brikama with a chauffeur driving the U.S. embassy’s vehicle and we got out and there was a whole lot of greeting. In the Mandinka culture, any time you meet anyone who matters, it’s: “How are you?” “I'm fine.” “How are you?” “I'm fine.” “How is your mother.” “She's fine.” “How was your father?” “He’s fine”… You name all the family members, and you start establishing family relationships and commonalities, and finally, you get down to the subject that matters.

So it went like that. Everyone was shaking hands, and then it was, “O.K., we can go now.” We were going to live there. Everything was worked out: how much we would pay per month, where we would stay... We would move in the next day. Bai Konte’s second oldest son Dembo was giving up his house for us. We didn't know a word of Mandinka, and they spoke pidgin English. There were no water pipes to turn on and off, or to flush with. No electricity. We were both given names to signify very high status in the Konte family. My name was now going to be Jali Braima Konte, Jali being professional musician, and Susan was Mariama Mbaye.

Marc and Susan were immersing themselves in the Gambian world of kora, close to where the instrument originated some centuries ago. The kora came to Mali only in the mid-20th century. Sidiki Diabaté (Toumani’s father) and Djelimady Sissoko (Balllaké’s and Sirifo’s father) were among the first Gambian players to bring the kora to Mali.

Sirifo Sissoko: In Gambia, it's a different style. The men do the singing and play the kora at the same time. So when my dad and Toumani’s dad travelled to Mali, they were confronted with a different kind of music. There was ngoni. There was balafon. There were all these instruments over there, and for them to really count, they had to embrace those instruments and play together with them. So they changed their tuning and their style. Sidiki and Djelimady, even though they were from the Gambia, they became the style in Mali. They did a good job, so the president gave them a house to stay in. But to be truthful, somebody else brought the kora to Mali before my dad: Batourou Sekou Kouyaté. He traveled to Gambia and learn the kora way before Sidiki and my dad. I would say probably in the late ‘40s.

Lucy Durán: Barourou Sekou Kouyate was a wonderful kora player with a very original style. I hear his music and it reminds me of raindrops on water. Slow raindrops. Ping, ping, ping. Very clear. Every note perfectly articulated. And when he strums the strings it's like bells ringing. It's very evocative, extremely musical and melodic. It's that balance between virtuosity and creativity and absolute groove.

Marc Pevar: My first experience of actually hearing and seeing a kora played might have been the first night that we were at the Konte compound, sitting cross legged on the floor, with the rest of the family all sitting on beds gathered together with one candle lighting the room. I'm sitting with my face perhaps a foot and a half away from his fingers and the strings of the kora in this strange, low light, and the strings are made out of pretty clear nylon. So you could sort of see where they were, and I could see his fingers. But I couldn't for the life of me figure out how the music was happening. It was like something magical, seeing it that close and realizing that I didn't know how this was happening.

I spent a long time trying to understand what was so distinctive about the sound of the kora. I think I understand it now. With the guitar, or any fretted instrument, most of the time, you hold down the string and you pluck and cause it to vibrate. Then you lift off of that fret and that first sound is gone. It's not there at all, not a shred, not a ghost.

But with a harp, when you pluck a string, until you physically dampen it, stop it with your hand, or until the vibration gets so low you can't hear it anymore, that sound keeps going. So if you're playing guitar, you can get six sounds out of the guitar. With a kora, with 21 strings, you could have 21 sounds happening at any one time. Usually it's going to be 10 to 14 because certain notes are used very seldom.

This is what makes this family of harps so different so different from guitars. It's more like listening to Debussy or an orchestra that's playing almost waves of colors, sounds that have wonderful coloration that blend together. Debussy's compositions, like “La Mer” and things of that nature, are much closer to what you can do with the kora as a soloist who takes a melody and starts taking a repetitious pattern and slowly changing the accent, or taking one note out and putting another note in.

This is something that Bai Konte was extremely good at. He would take a basic melody and, if you're paying attention, you realize that he's playing a variation of that melody, and then you say, “But when did he stop the other one and start the new one?” But it didn't really happen that way. It's very slow, one little note change at a time, one little rhythmic accent change at a time, and it keeps moving and shifting, and then with a sly grin, the really good musician will return to the first melody and then throw in what are called birimintingo. Birimintingo are these very fast runs, sometimes more than double time, blisteringly fast, and then he would slow the pace down to a snail’s pace again.

Sirifo Sissoko: Birimintingo is improvisation. Someone can actually teach you the kumbengo, the accompaniment for a song. But birimintingo is something that depends on your emotions and your feelings. “Can you show me the birimintingo for this song?” No. Nobody can show you the birimintingo.

Sirifo notes that when two kora players play together, they have lead and accompaniment roles.

It's not like a competition thing where everybody's got to show their skills. No. You want to combine to be something beautiful, like my dad was with Toumani’s dad. Toumani’s dad would do the solo and my dad would do the accompaniment. Does that make my dad a lousy kora player? No. It doesn't work like that. Everybody knows everybody's specific value.

Lucy Durán: What makes a kora player great? It's very subjective ultimately, but I think we need to go back to ideas about musical greatness from the culture itself. There's a term called ngara that means master musician. Ngaraya is musical mastery. This goes beyond just kora. It's singing and any other form of musical performance particularly by the griots or the jalis. Ngaraya, musical greatness, implies that the music goes beyond mere entertainment. It has a power, the ability to make things happen. It moves you to do great things.

Marc Pevar: Bai Konte was a good teacher. The way it worked within the compound is that the people who knew would show the others who didn't know. So he would show me something, and then the other musicians that were around who are very advanced, would be sipping tea or chatting, but they'd hear what was happening musically. "No, Braima. No, Braima.” or “That's good. That's good. Keep this." So they were all paying attention and making sure I got it right.

I was taught that “Kelefaba” is the first song that you play. There's a certain bass pattern that you play, and I got the right hand right away. But then the left hand was peeved, because it couldn't do it. After playing guitar for years, it wasn't used to picking. Eventually it caught on, and I loosened up. I would walk around town with my hands to my side and my fingers would be busily rehearsing the motions to coordinate my thumb and first finger.

Marc ran into a common problem that Westerners have whey they try to learn African music. He was focused primarily on getting the notes and the finger moves right. The rhythm came afterwards. For the Africans, it was the other way around.

Marc Pevar: The apprentices would sort of flail away at all the strings with their thumb and first finger and make this kind of cacophonous, to me, sound, and then over a period of time, maybe 10 minutes, 15 minutes, I would start hearing the right notes emerging from this messy mixed up stuff. They were starting with the rhythm. What I learned is that, as a performer, what is most important is not to get every note right; it's to keep the rhythm going. Because when you keep the rhythm going, the other musicians will say, “Braima, you had a little trouble on that C-sharp." They will notice that, but the audience never notices if you are a little off here and there. But if you lose the rhythm, they notice instantly.

Sirifo Sissoko came from a very large musical family in Mali with Djelimady Sissoko as patriarch. Sirifo’s path to learning the kora was, naturally, a little different that Marc’s.

Sirifo Sissoko: My dad used to say, we have a special connection with the kora. When we play the kora, we face the instrument to us. You are communicating with the kora. You don't play like you're playing a guitar or ngoni. It's facing the public, not you. But with the kora, you are meditating when you play it. It's like you’re having a dialogue with your kora.

My dad had three wives and about 30 kids. He had two koras. [One of them was kept at the rehearsal space of the Ensemble Instrumental du Mali, where Djelimady was the kora player.] But the kora at home was in his room. It was not available to everybody. I would say Ballaké was the luckiest one. He would sneak in all the time and touch that kora. My dad passed away in 1981. My mom was the first wife, but she was from Senegal originally, so she decided to leave Ballaké behind because he was 13 or 14 and he replaced my dad in the Ensemble Instrumental. So with 30 kids and three wives, my mom decided, “O.K., I'm gonna take the little ones to my dad.” That's how we found ourselves in Cassamance, and I found myself in school and learning to play kora there.

The first step is that you listen, and then you put your hand on the kora. If you make a mistake, that's the time that somebody comes to correct you. But they don't just sit down and give you the kora and say, "Play this." Let's say for example I’m trying to play “Allah L’aa Ke.” I play the notes but I make some mistakes. Ballaké will come and complete it. "OK, let me show you." But the first initial thing, it's got to be you. You’ve got to want it, and then as you go along, someone will correct you.

Eventually, with Bai Konte’s enthusiastic permission, Marc began to record.

I had bought two cardioid mics with turning capsules, which turned out to be invaluable for the way I recorded the Bai Konte album. The way I recorded apparently was novel. I didn't know any better. I just knew what sounded good. I wanted to get the sound of having your ear a foot away from the kora, roughly. I placed one microphone in line between the mouth of the singer and the bridge of the kora, with the capsule rotated so it was facing both the mouth and the leather of the kora. The second microphone was placed on the back of the kora, opposite the sound hole to get the deep booming percussion sound that comes from that area. That one was perhaps eight or 10 inches away. And those two microphones are the sound you hear on the Rounder recording.

Before Rounder decided to release that Bai Konte album in 1973, Marc had sent from Gambia a sample recording to Moe Asch at Smithsonian Folkways.

I wrote and said to him, “Can you talk to people in the record business or the music business?” He was the only person I could really think of because I had bought several of his albums. So I got his address and I sent him a letter, and I went to Radio Gambia and made him a copy of one tape. He wrote back and said, "This is really beautiful music. I don't know where you found a recording studio of this quality. It's quite amazing. But this is not the kind of music I look for. I'm looking for the music of the regular people. Too much engineering has gone to this with the dynamics. There are too many beautiful highs and lows. I want the regular musicians."

So I wrote back and said, "Well, Mr. Asch, I recorded this in the living room, single takes, no engineering. The lows and the highs are just how this man plays. He's one of the very best in the country and people try to play like him."

So he said, “O.K. Well, I'm interested in this stuff. When you come back to the country we'll talk.” He was actually going to take the demo I had sent and put it out and I said, "No it's not long enough.” I'd only sent him 20 minutes or so.

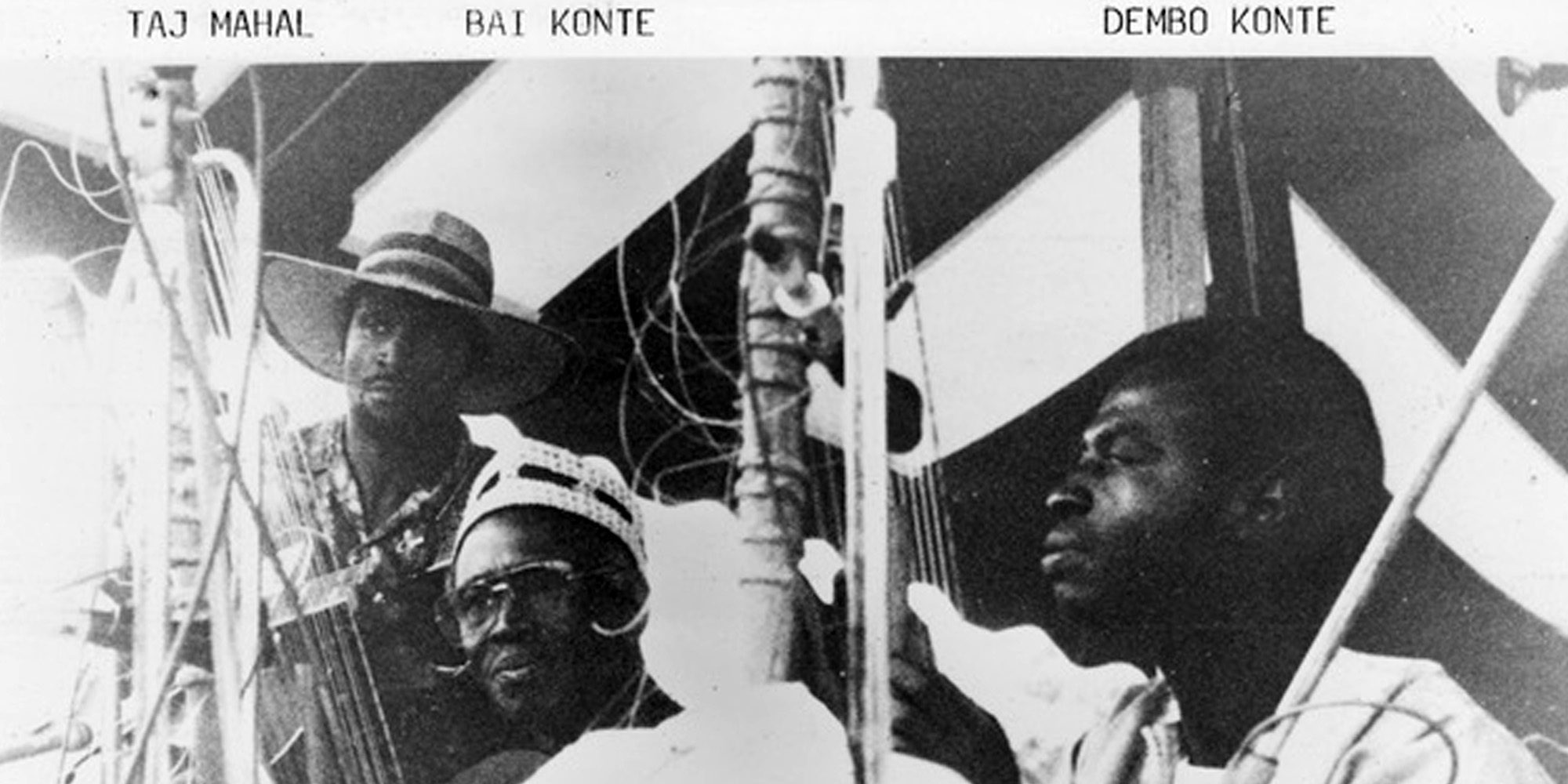

But things took a different turn when Marc chose a famously psychedelic cover image for the album. Moe Asch refused to release an album with a color image, so the record came out on Rounder Records. That striking cover image led directly to Marc’s friendship with Taj Mahal.

Marc Pevar: Taj needed to change his guitar strings, and he was in Harvard Square in Cambridge. He was walking along the street looking for a music store and on the way he walked past the record store and did a double take when he saw the Bai Konte album. He walked in, picked it up, read the back, bought it and took it back to where he was staying and played it two or three times. My phone number is on that album, so he called me. We talked for over two hours, and he told me that his dream was one day to go to Africa. [Taj did later travel in Africa as part of a State Department tour.] He was sure that he had ancestral roots among musicians in Africa. He was very taken by the music and would like it if we would get together sometime when I could play kora and he could play guitar and get the feeling of what it's like playing with a kora. This around 1976, ’77.

Susan Pevar: The funny thing about that picture is, it was actually a mistake. We were so broke so we were sending our film home to a friend, who claimed he could do the printing.

Marc: My friend processed the film, Ektachrome slide development. I saw the pictures when the slides came back and our friend was very apologetic. He said, "I don't know what happened, if it was a temperature or what, but some of them got solarized.” I looked at that and thought, "Oh my goodness, this is an album cover." This is the middle of the psychedelic era.

Susan: Taj Mahal might not have spotted that album if it hadn't had that picture.

Marc: Yes, if my friend hadn’t made the development mistake.

Marc later curated concerts for Bai Konte in the U.S., including one featuring Taj Mahal, Bai Konte and Elizabeth Cotton.

It was a concert held at the Bretton Woods Hotel, a very famous hotel right at the foot of Mount Washington. So you’ve got Bai Konte, who is a very traditional, African classical art musician, and then you had Elizabeth Cotton who many people consider to be the mother of the Piedmont guitar-picking style, where you play the melody and counterpoint simultaneously in the bass and the treble, and sometimes mix things up in the midrange. She is the person who popularized that style called “cotton picking.” And then you had Taj Mahal who is a great interpreter and innovator, and a marvelous performer. He just holds the audience in the palm of his hand. So these three, one after the other, performed, and for at least 10 years after that, NPR played that concert nationally several times a year.

Then, around 1979, there was a concert at the Folk Forum at Madison Square Garden, a memorial Woodstock celebration, 10 years later. It ended up they produced a VHS out of this. I have never seen it. I can't find a copy. I’m told there's a copy in Paris at the national library. There's got to be one in Hollywood. Anyway, Taj Mahal with Dembo Konte and Bai Konte was one of the acts selected to be there, along with Canned Heat, Richie Havens and a few others.

Susan: We found some reviews, and many of them were kind of negative, except for Robert Palmer at the New York Times, who said Taj Mahal and the kora musicians were the bright spot it was otherwise a lackluster performance.

In 2020, Marc had planned to mount a tour with the third generation of musicians he had met in Brikama in the 1970s. The Great Gambian Griots tour was originally planned with three young kora players. Of course, all this was scuttled by the Covid-19 pandemic, but Pa Bobo Jobarteh, and Jali Bakary Konteh did come the U.S. to perform and record in 2022, and the plan is for Great Gambian Griots to return early in 2023. Watch this space. Here’s what Marc said about these musicians back in 2019.

They can play that first Bai Konte album pretty much note for note. Being a musician, you might notice small variations here and there, but to the casual listener, it's the same thing. They studied and came up that way, and at the same time, because they're true musicians, they each have their own interpretations of those songs, and their own style. I had them make videos for the African Cultural Encounters website, I had to do a mixture of traditional songs and their own improvisations or songs with lyrics. Pa Bobo is a master lyricist in his home country. He's similar in some ways to Pete Seeger. Where Pete Seeger could take a topical thing like war and peace and turn it into “Where Have All the Flowers Gone.” His songs are more pointed because the kinds of issues there are a little different. Pa Bobo wrote a song called “Peace, Love and Unity” when the country was under the oppression of 22 years of a dictator, Yahya Jameh, a terrible person. He did really nasty things.

So Pa Bobo wrote this song “Peace, Love and Unity,” and started singing it, and then people around the country started singing it in towns, and word got back to the dictator that people were very hard to manage and that they were resisting him. He attributed, rightly or wrongly, this to the fact that people had recovered a sense of dignity and hope, which was the theme of this song. It got to the point where the dictator put a $10,000 price on Pa Bobo’s head. And he had to flee and hide in Senegal to save his life. He was only able to come back after the dictator was deposed.

Lucy Durán: I suppose I have to confess that I am a bit of a traditionalist. I'm a bit old school. I like really the oldest ways of playing. Having said that, I am complete fan of Ballaké Sissoko who sings with his kora, in both senses. His playing his music is infused with melody, and a kind of spirituality, which I consider to be a sign of musical greatness. He’s very dexterous, virtuousic, but that isn't the main point of how he plays the kora. It's the soul in it.

Sirifo Sissoko: Ballaké in the studio setting is nothing. Ballaké, even sometimes in the concert setting, is nothing. But if you see Ballaké in the compound late at night and you sit next to him when he's just playing his kora, it's something. I get goosebumps. I cry to some of the stuff he actually plays. It's powerful. To me a great kora player is someone who really plays with melody, not technique. Because the kora is basically melody. You sing through the strings, like you're singing a song. The kids nowadays are doing this fast stuff, but it doesn't mean anything. They're just doing technique.

Lucy Durán: Although I celebrate the fact that there are so many young kora players who are brilliantly virtuosic, and are recording widely and doing all sorts of fusion stuff. It's all excellent, and the kora has really become a very established instrument now, but I would say that the whole idea of ngaraya, musical greatness, is sort of fading away and instead is being replaced by physical dexterity, running up and down the strings of the kora with machine gun speed with little real musical context. So at the end, you are impressed by the dexterity, but you're not moved by it.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles