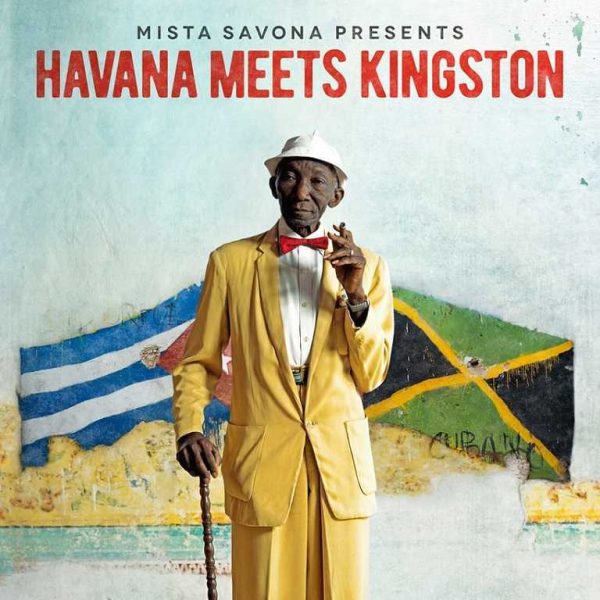

Jake Savona is the producer behind Havana Meets Kingston. After the project’s debut album release in 2017, a version of the band—combining musicians from these two musical powerhouse Caribbean islands—toured twice. Then came the pandemic. By then, Savona was well into creating a follow-up album—Havana Meets Kingston, Part 2. But after a pause the work continued, and now the follow-up album is here. It’s an ingenious, varied and rollicking set of tunes featuring some extraordinary artists, including the legendary Jamaican rhythm section Sly and Robbie, and Cuban funk rising star Cimafunk. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Savona—who goes by Mista Savona—at his home in Australia to discuss the project. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Greetings, Jake. Am I reaching you in Melbourne?

Jake “Mista” Savona: No. I'm in Byron Bay, about halfway up the east coast of Australia. It's the eastern-most point. But I grew up in Melbourne.

We've done a couple of shows recently hosted by a DJ in Melbourne, a Zimbabwean woman who goes by DJ Kix. Her show is called “Afro Turn Up.” Have you heard of her?

I think I have. She's doing big things.

She is. It's great to have some new young energy on our program. So, coming to Havana Meets Kingston, I’ve really been enjoying the new album.

Oh, you have it. I think you're one of the first. Even some of the artists don't have it. And you've heard the first one also?

I have.

O.K., so you're going to be the first person that I ask, "How do you think they compare? Do you think the second one is worthy?

Absolutely. It's terrific album. Beautifully produced. Great performances. Such a cool idea. It's so crazy about the Caribbean. You can have two islands that are virtually neighbors, but because the colonizers spoke different languages and had somewhat different cultures, you get a completely different result. But of course the common thread is Africa.

Totally. I would say language and economics. There is extreme wealth on both islands, but mostly they're both really poor compared to the West. So you’ve got the economic limitations, then in the late ‘50s the socialist takeover in Cuba. But actually, according to some of the old Rastas, a lot of Jamaicans used to go to Cuba all the time in the ‘50s. The sanctions happened after Fidel took over. Suddenly Cuba became cut off, and that prevented this exchange of cultural ideas from happening.

I know you had been producing reggae and dancehall acts. But how did this project get started?

My first trip to Cuba was 2014. From Havana I went to the opposite end of the island, Santiago de Cuba. Because reggae is not big at all in Havana. I don't even think in Havana Cubans really understand reggae. But in Santiago, they can listen to Jamaican radio. They're so close that they can tune in, so they've been hearing reggae all the time, and that's where there's this little bastion of popularity for reggae in Cuba. I also think the reason Jamaican music isn't bigger on the island is literally because of the language. Dancehall would be the perfect music for Cubans, but they don't understand the Jamaican patois at all, which is why reggaeton is so massive. That's the modern equivalent, which I have very mixed feelings about because of the production and the Autotune and all that.

But going back to the ‘50s and ‘60s, you can actually hear in Cuba a lot of the percussion, like the guiro, is doing similar things to the guitar skank in reggae. But pretty much from the ‘50s on, the music really split, and there hasn't been a project like this. Some Jamaican musicians have gone into Cuba and done some tours, but very rarely. This is literally the first time, these two albums, Havana Meets Kingston, Parts 1 and 2 is the first time a collaborative project has happened.

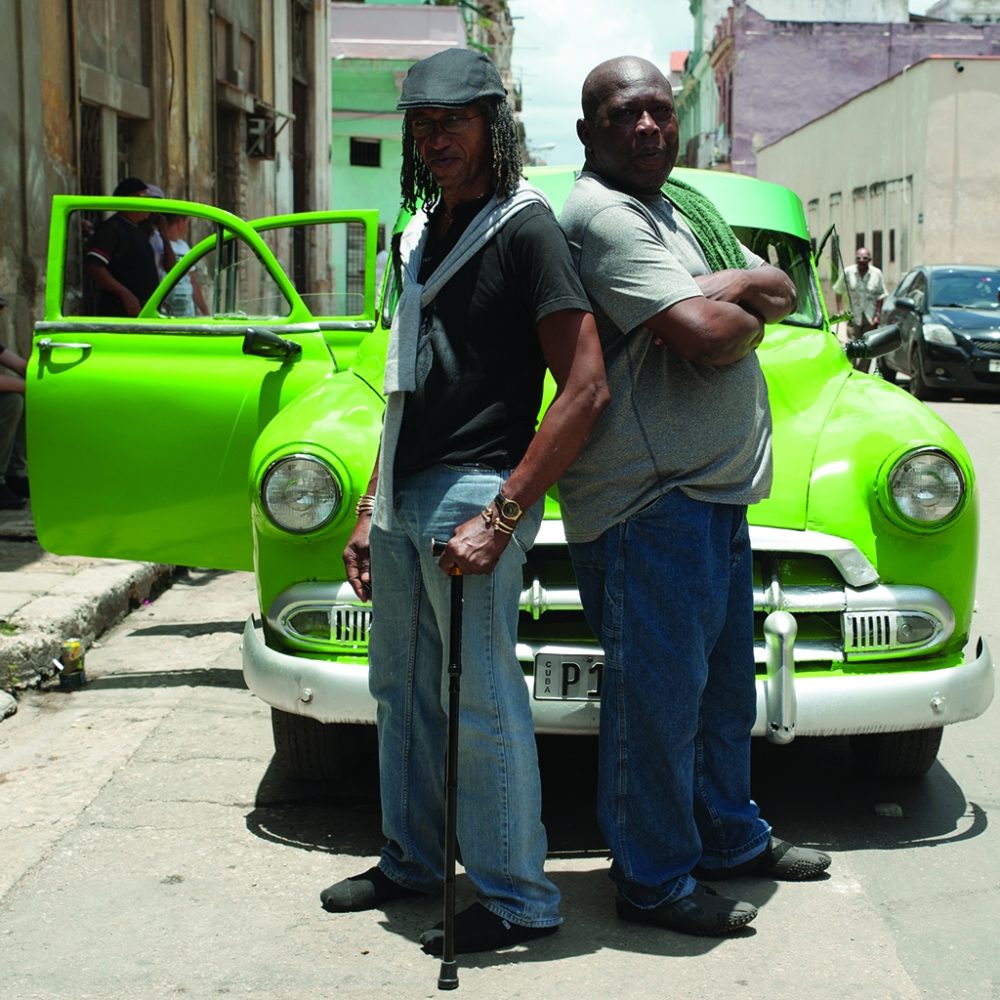

I had been in Jamaica six or seven times before I went to Cuba. I had worked with Sly Dunbar before. So on that 10-day trip in 2014, on the last day I was sitting in this really nice café in Havana, listening to rumba. And I just had a vision of the music coming together. I was sure someone had done it before.

It seems like an idea that was going to happen one way or another. It was inevitable.

Yeah, one-hundred percent. And I was the lucky one. I could feel it wanting to happen. And it's been brilliant. Some of the Cuban musicians on the project say it was the best thing that ever happened to them. They had never toured outside of Cuba or had an opportunity like that. It's been magic. So getting the second album out and ready has felt even more of an achievement after a pandemic, a global depression and not being able to tour. My U.S. record label Cumbancha, and also my French label, Baco Records, were just saying, “Wait, wait, wait. We don't want to release this record until there's a touring possibility.” I've been so impatient for the world to hear it, so I'm very happy. We just launched the album a few days ago.

Was this album recorded before the pandemic?

A lot of it was recorded before, and a lot during. As you know, I am based in Australia, and last year it was impossible to leave. You had to get special permission to leave Australia. And luckily, in December 2020, I did my research, I did my application, and I was accepted. I got to go to Cuba for three months. I was able to do all the final touches and film some beautiful music videos despite being in lockdown. We just had to make it happen. So the record has been four years in the making to be honest. Part one came out in 2017, and I started work on the second one in 2018.

This is so interesting to me. You know, our whole mission at Afropop is to look at African and African-derived music and how it affects the world. And you couldn't think of two more influential genres than reggae and Afro-Cuban music in terms of global impact. Tell me about some of the musical challenges you faced in bringing these two traditions together, I guess especially in the beginning when the artists were not familiar with each other.

One of my favorite things about the whole recording process is that we were able to record at Egram Studio in Havana, which is where the Buena Vista Social Club recorded. It's just an amazing room and vibe, basically a 1940s music studio. It's the oldest recording studio in the Caribbean, and one of the oldest in the world. I was really lucky because it was all booked out and I had my heart set on recording there. At the last minute I met the right person, a Cuban high-priest percussionist, very respected, and he was able to open that door. I think he went in and told them personally, "You have to change the dates and make space for this." And they did. We got 10 days there.

I'll never forget the first session. Basically I had all the ideas for the songs. I charted them out, but I did simple charts like jazz charts, just chords. I didn't want the musicians to be too locked into anything. Just give them a structure and allow them a lot of freedom. But anyway, no one could speak the same language. The Cubans speak zero English. And the Jamaicans spoke no Spanish. But as soon as everyone sat down… I sort of guided Rolando Luna at the piano. He now plays with Buena Vista. I gave him the parts and the tempo, and literally, me and Eric Coelho, my Australian engineer, as soon as everyone started playing, we just looked at each other and said, “Oh my God, this is going to work.”

Musically there was such a high amount of listening and awareness, and so much respect. I'll never forget the Cubans seeing Robbie Shakespeare sitting in the control room, when they actually saw his fingers on the bass. Because in Cuba they don't have this deep sub, they don't have the Jamaican sub at all. On double bass they are virtuosic. But when Robbie started digging into those low notes... It's his fingers that get that sound, and the Cubans were just in amazement. The first track was this beautiful instrumental. The rhythm was rolling with this slow dub thing, but with Cuban percussion which you never hear in Jamaican dub or reggae. It was just instantly clear that the musical chemistry was on another level.

Maybe the language is different, and the cultural understanding is different. You know, Jamaican Rastas smoking weed and with their whole spiritual basis of the music—the Cubans knew nothing about that. They are worlds apart in many ways and yet they're totally connected by this common African ancestry. And we could feel that. It just locked in.

How wonderful. So when you started making the second album, in the initial sessions before you knew that COVID was going to happen, you wanted to put together something you could tour. But you also have a lot of guest artists, people who might not necessarily be available to tour, people like Cimafunk. How did you work out that balance?

It was actually halfway through the recording sessions that Robbie, of all people, mentioned that. His attitude through the whole session was kind of gangster. He didn't talk a lot. I'd ask him, "Robbie, is everything O.K?” And he'd say, "Yeah, man." Sly was the much more up front and friendly guy. Of course Robbie has passed away now. [Robbie Shakespeare died in Dec., 2021, in Miami.] But my memory of him in the studio was just as this big presence but quiet. He just got on with the job. But it was actually him, halfway through the sessions, who asked, "So when are we taking this on the road?”

As stupid as it sounds, I hadn't even conceived of touring this project. We did eventually tour in 2018. That was the big world tour. We even played the Royal Albert Hall as part of the BBC Proms. That was amazing. We’re hoping to get permission soon to release that.

I read about that concert. You must've played in New York at some point.

Actually we haven't toured America yet. We did a big Europe tour. U.K. Two Australian tours. We've done nothing in America yet, but we’re hoping later this year, or definitely next year, as things open up. It was all in motion, and then the pandemic hit. But when Robbie first suggested that, it was like a train had struck. "Wow, imagine this band on the road!" All my energy had been organizing the sessions, getting the Jamaicans to Cuba, getting the Cubans organized, getting my charts organized. It was, and is, a huge project. Suddenly this idea of touring came, and when we did tour, oh my God, it was the most incredible band.

But when you got to this second album, you were thinking about touring. Do you think you could actually get all these people on the road?

I think there would be some concerts where I'd hope we could do something big. We've done the Royal Albert Hall, my dream is now Carnegie Hall. I'm putting it out to the universe now, that there would be some concerts were we could invite Cimafunk and a host of these different singers to be guests. You mentioned Cimafunk. I actually knew him before he was calling himself or his group Cimafunk, and before he was well known. He was Erik Rodríguez, performing with a group called Interactivo. You should check them out. They are great. So we had seen him perform live, but literally, we recorded his vocals in this ghetto studio. We did two tracks. There's another unreleased song as well. And then seeing him blow up. Now he's become this huge star of Cuban funk.

We saw Cimafunk at WOMEX last fall, and it was really the most powerful set in the whole event. Staggering. Like seeing James Brown with a smile. But going back to the tour idea, you do have a core band that could put on a show even if you didn't have all those guests. Right?

Totally. Well, Brenda Navarette, who's on three tracks on the record, is totally amazing. She sings, she raps. She plays percussion. She is just this powerhouse, a fireball of energy. She has been on all the tours and she is one of the key members. Julito Padrón the trumpet player also sings beautifully. He's another key member representing Cuba with the vocals. We're doing a European tour this summer in July. So those two are definitely coming on board for that. And then representing Jamaica for this tour, we've invited Micah Shemaiah, who has two tracks on the record and also has a beautiful voice. So, yes, it'll be quite a different lineup for the second tour compared to the first. But the idea of the stage show is to present a mix of the songs. We also do some classic Jamaican riddims, and a few more traditional Cuban songs that aren't on the record. We just try to get a mix of both.

The thing about Havana Meets Kingston, as you've probably heard on the album, is there is some traditional Cuban stuff, some rootsy Jamaican stuff, and then tracks combine both. The idea of the album is not that every song on the album has to be a mix. It's more like I want to take people on a journey, almost touching on Buena Vista Social Club, and then taking them to modern Cuba and then the roots tracks were recorded at Tuff Gong in Kingston, Bob Marley's studio, and then show them a mix of modern rootsy stuff. There's no dancehall on the record, but there's up-to-date contemporary style vocals and the popular DJ style. So we’re trying to give people the sense of the old and the new on this record.

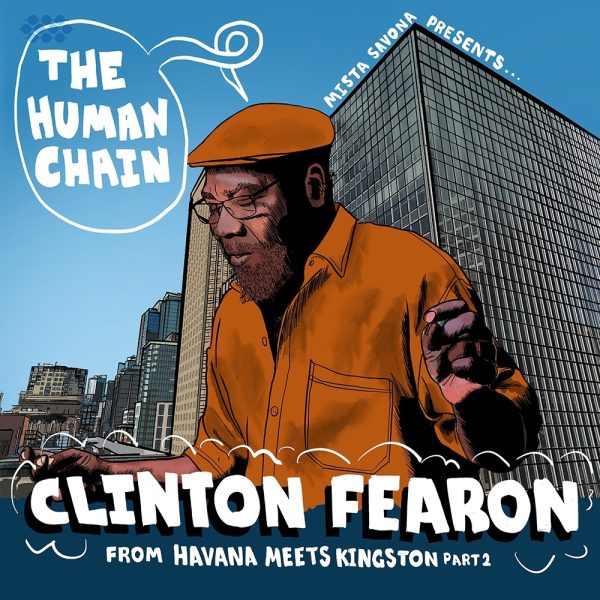

I get that. We just posted the Clinton Fearon video, which I love. I wanted to ask you about the era of styles that you are dealing with. You just described it quite well, but it's interesting that you stop on the Jamaican side before dancehall, and even on the Cuban side, we’re not getting timba, hip-hop, reggaeton. Talk about that choice.

Definitely in the mix and the production, I don't use any Autotune on vocals. Everything is recorded in the way albums were recorded in the ‘60s and ‘70s, the whole band in the room playing together. Some isolation. I put the drums in a different room so later I can do remixes. Sometimes we had 10 musicians in the studio together. So you can imagine how much sound that is. Later in the mix I needed some freedom to pare things back.

You know, I just wanted to make great music, and I'm not really a fan of timba. I mean, I love it, but sometimes it’s just so hectic and busy. On the track “Guarachará,” there’s that last section when the whole band comes in and gets close to that.

That's the track that starts out like flamenco.

Yes, it starts flamenco, and then there's a kind of Afrobeat section, and then the end is this salsa/timba feel. “Guarachará” for me is one of the most evocative tracks I have ever produced. When I was in Cuba last year in lockdown, almost at the end of the trip, I found this beautiful colonial castle from the 1920s. It had been a gift from Spanish king to a Cuban family who helped save his wife from one of the wars. So we recorded that music video there. We got everybody dressed in 1930s, ‘40s style clothing. We got the old cars and everything. I really wanted to capture that feeling. And then halfway through, it switches to modern Cuba. Suddenly everyone is in new clothes and it's a party. For me that music video and that song are just the best.

So there are modern elements in there. But I guess I'm going for a more timeless sound with these albums. I want enough of that modern flavor to give people a sense that this is something new, but I'm just not a fan of commercial contemporary Autotune. I'm just not.

So what you think of the new Afrobeats out of Nigeria?

I love Afrobeats. I deejay a lot, and I play a lot of Afro-house, Afrobeats. Of course I love the 1970s Afrobeat with Fela, and I love the new music too. As David Rodigan [BBC] says, it's like dancehall, but more approachable. It's more gentle. And yet you can still dance to it. I absolutely love it. I've even got an unreleased track with Afrobeats feeling with Capleton, who is a really big Jamaican dancehall artist. It's such a good mix of those two styles. The thing I love about contemporary Afrobeats is that they're so influenced by Jamaica. They're so influenced by dancehall. And yet lyrically and with the vibe, there's a gentleness there. Jamaican dancehall is so aggressive. And now dancehall is dominated by the trap sound. It's quite heavy. Afrobeats has this lovely lilt.

I think that's because rhythmically, a lot of it is based in highlife, or even a kind of Congolese clavé-based timeline, rather than the funk and hip-hop direction.

That’s right. There's not that aggressive snare. It's a softer sound. And then that African guitar. Straightaway that gives a flavor. But the vocals are totally inspired by Jamaican DJ style delivery. They even use some Jamaican patois, so they're clearly highly influenced by dancehall. They're also using their own mix of English and Nigerian patois as well. So it's just this incredible fusion.

Let's talk about some of the songs on the new album where you do get these genres to kind of talk to each other. Take “Lágrimos Negros.”

That's a completely traditional song and presentation. I guess you could imagine the Buena Vista Social Club, but having Sly and Robbie instead of the Cuban rhythm section. It's a Jamaican groove, the Jamaican one drop. But the piano and the Cuban percussion and vocals are very traditional, like a Cuban son style that you might hear in a Buena Vista type group. That's a simple kind of fusion. I love it. It works very well. You almost don't notice. And then it's like, "Hang on. That's a Jamaican drumbeat."

And then there’s “Havana Meets Kingston,” which is consciously fusing the two styles. I'm curious about how these songs come together. You've composed them to some degree, but I imagine there's some development that happens when the musicians come together.

Yes, one hundred percent. Like I said earlier, a lot of the charts are just sketched out. Chord changes. I would give Robbie some ideas, some bass lines, but he would almost always change the bass line. And of course in most cases it was better. There are only two tracks where I said, "Please keep just a little bit of my line." So that was the idea: charts, but keep it open so they can bring their own creativity. Rather than having the horn players having to study these charts and play exactly what I wrote, I wanted to give them the freedom to come up with their own lines. So it's very collaborative.

Those initial sessions, when I brought the full band in the studio in Havana, we would do basically the instrumental tracks, and then vocal choruses afterwards. And then later I would go to smaller studios and work one-on-one with the singers. At that point, they would come up with a lot of new ideas. Definitely when they were doing vocal tracts, most of the singers would come up with their own lyrics and melodies. And the choruses were very collaborative. We worked them out together. “Siempre Si” is a really nice example of that. It's a really nice Jamaican kind of groove…

Right. And then the vocals bring in the Cuban element

Totally. And I love this one because the lyric says, "Always yes, never no." And then in the next lyric is a Cuban expression for "going with the flow." I just love this chorus so much. So instrumentally, I would bring all the ideas together. That's what I do; I'm a music producer. But then I give people the freedom they need, and especially with the vocals. Let them come up with their own ideas. Sometimes I need to steer them away from more cheesy kind of territory, to get something a little bit tougher or rougher. But mostly the musicians and singers love the ideas, and they just dig deep. That's how it happened.

So in the second sessions, was there any progress on the language front? Were they able to speak to each other more?

Actually yes. Cimafunk’s English. Brenda’s English. They've come a long way. For Cubans, they are more and more learning the lyrics to songs that they hear with the internet opening up. They don't hear English on Cuban radio. That's all in Spanish. The first few times I went to Cuba, the only way you could get internet was if you go to a park and you'd have to pay for a wifi card, and a lot of Cubans couldn't afford it. Whereas now, finally, as of about three or four years ago, they’ve got internet. That was a new thing for them. It's still very expensive relative to their income, but Cubans, like everyone else, are becoming addicted to the internet, which means they're hearing many more styles of music, and a lot more music in English. I wouldn't say that the Jamaican Spanish has improved.

O.K. Maybe there's less incentive there. I love the instrumental track with Barbarito Torres on laud and Rolando Luna on piano, “Lo Qui Quieres.”

That was totally a flashback to Buena Vista. I had them in the studio and I said, "Let's do something with just you two." And they wrote that song on the spot within five or 10 minutes. It sounds like a classical traditional song, but it's actually something new they made for the record. That's the thing with this album. I wanted to take people on a journey. Suddenly they’re in Cuba, and then suddenly they’re in Jamaica, and I think that's one of the reasons people love this project, because you can't get bored listening to the record. It's not just one genre or one sound. It's a journey through two amazing cultures, these tiny little islands with very small populations that have had a completely profound influence on the whole planet.

What about this track “Reggae y Son,” which has this enormous cast of characters on it.

That was going for the all-out Cuban horn extravaganza, but using a four on the floor Jamaican steppers riddim. For that one, I just wanted a joyful, exuberant expression mixing the two styles. That was a really fun track to record, kind of the explosion track on the album, with everyone at once just going for it.

Then there’s “Slave Trade” with The Jewels. That's a ‘70s reggae act I had never heard of. There's a bit of a Burning Spear vibe on that one.

That's an amazing, little-known—apart from collectors—Jamaican vocal group from the ‘70s and early ‘80s. Finding that singer was an amazing story. I kept asking people and no one knew who they were in Jamaica. Finally I found him up on the top of Kingston in a little hut. Absolutely amazing. He hadn't been in the studio in over 20 years. He was living in utter poverty in this hut in the jungle right above Kingston. It was so hard to find him, but we finally did. He's blind, completely blind. His daughter was bringing food and water once or twice a week. He's living by himself blind, in a hut, no power. My visit was the first time he had ever had a foreigner come and look for him. He was so joyful. He wanted to perform. It's the most beautiful story. So two or three days later, we managed to find one of the other original singers of the group who he hadn't seen in decades either. We got them in the studio and that's how we actually recorded that track and some other songs.

What a story.

You'll find almost nothing about them online, though you can find some things on YouTube. And it is criminal that there hasn't been a CD compilation of their singles, because they are some of my favorite vocal harmony tracks from Jamaica. So much music in the world. It's hard to keep up.

Tell me about it. Our wheelhouse is all of Africa and the diaspora.

You could just pick one genre, say Afrobeat and funk from Nigeria, and you could spend your whole life just trying to listen to everything in that genre, let alone everything that's happened everywhere else, let alone what's happened in the last two weeks.

I also find that the deeper you dig, the more you realize how little you know. Any other song you want to mention before we wrap up?

The last track, "We Are One," was a riddim recorded at Bob Marley’s studio in Jamaica, Tuff Gong. It's the one track where I got to work with an amazing guitarist from Studio One: Earl “Chinna” Smith, who actually worked with Bob Marley in the ‘70s. He takes a guitar solo on that song. I'd love solo so much. It's a sound from like 40 years ago. Nobody plays like that anymore. Speaking of guitar, “Kingston Nights" is a beautiful guitar instrumental by our guitarist Bopee Bowen. He passed away a couple of years ago from a heart attack in Kingston. I'm really happy we recorded this instrumental with him before he passed.

Well, it’s a great piece of work, Jake. Thanks so much for speaking with us.

Thank you.

Related Articles