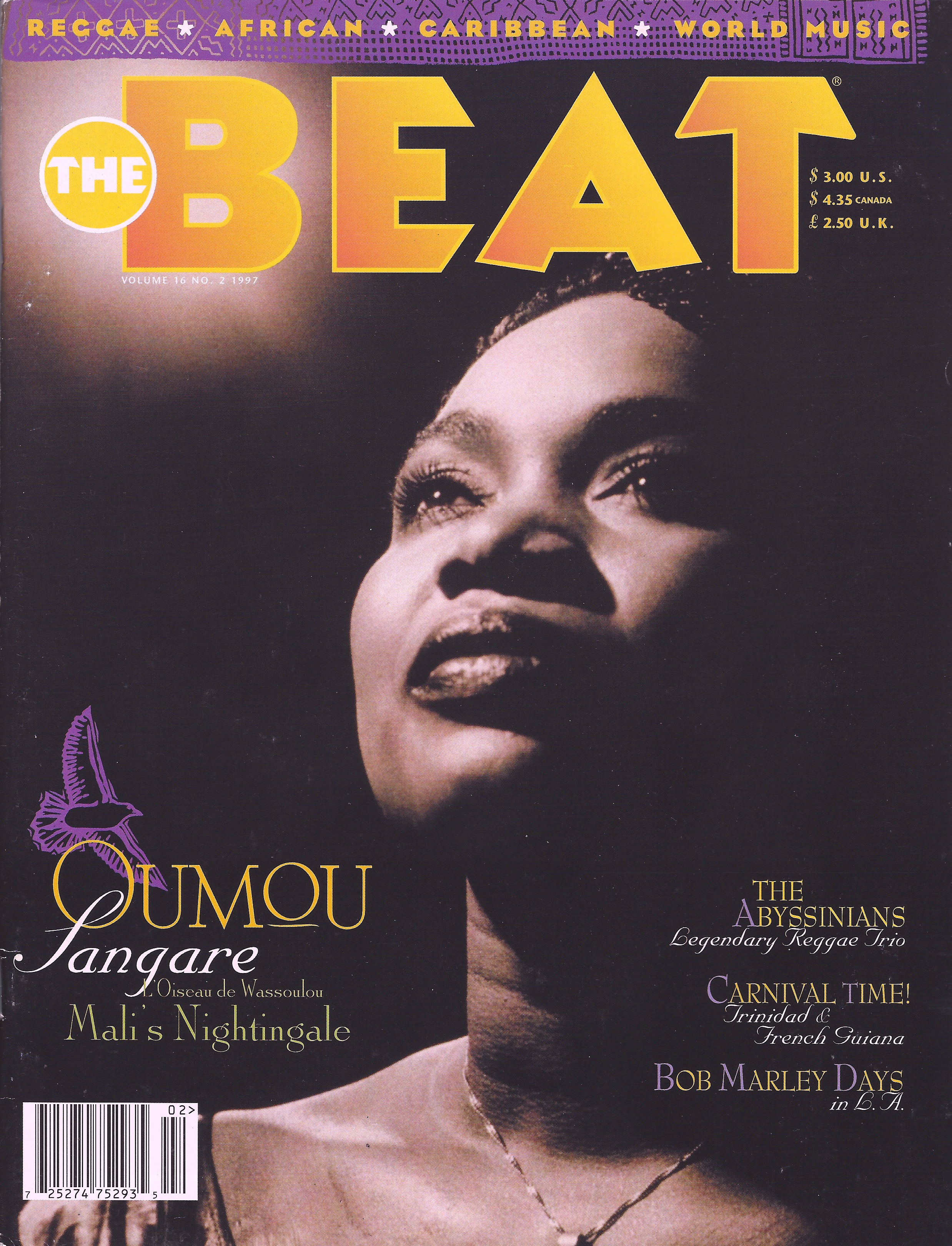

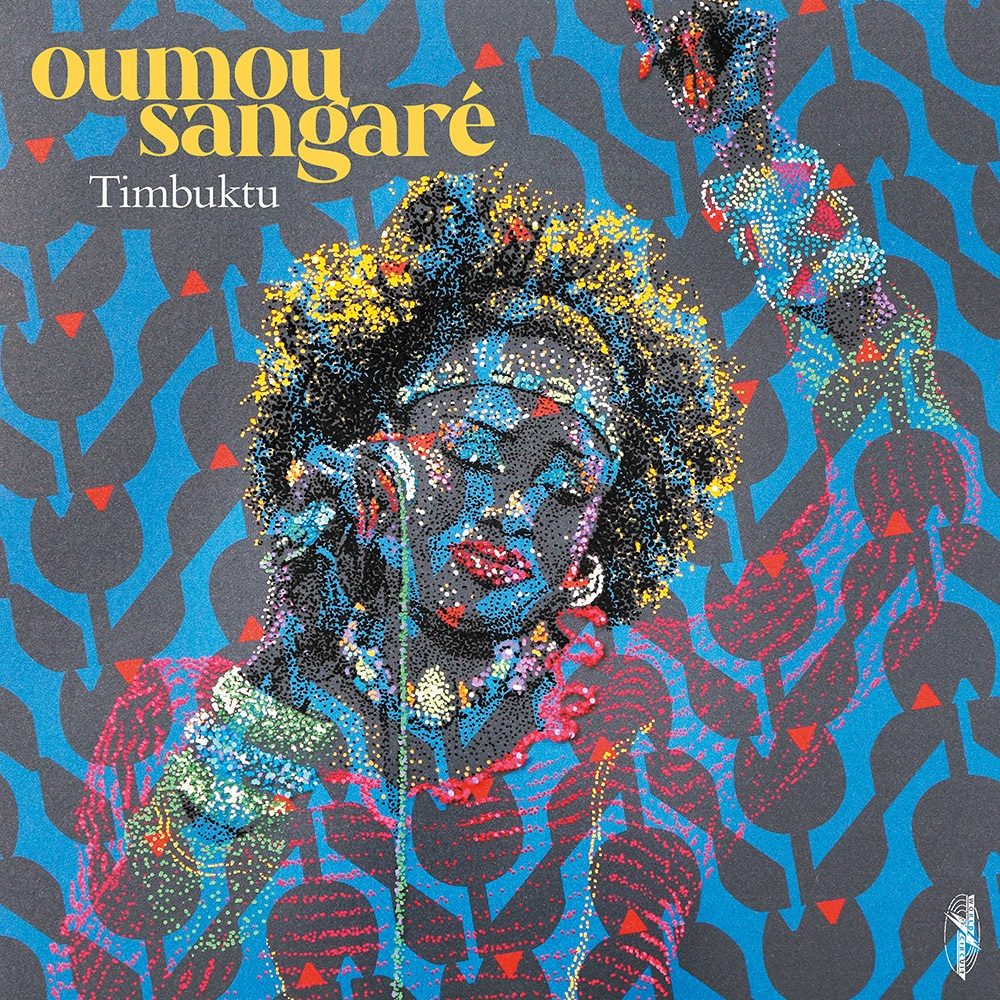

Oumou Sangaré has long been known as the queen of Wassulu music. Since her debut release Moussoulou in 1989, she has maintained a singular space in African music, substantive, dignified and blessed with a spectacularly affecting voice. As a rule, Sangare takes her time with new material. Her 2022 release Timbuktu is just her seventh album of new compositions in those three-plus decades. (Her 2020 release, Acoustic, offered acoustic versions mostly of songs from her 2017 album Mogoya, both on the No Format label in France.)

The time Sangaré takes with new material shows. The songs on Timbuktu are beautifully crafted and loaded with thoughtful messages, very much in tune with the times, even as she hews strongly to her signature sound. Banning Eyre reached Sangaré by Zoom in a Paris studio for a conversation about the album and the annual March festival she hosts in Mali’s Wassulu region. Here’s their conversation.

[Note: There doesn’t seem to be much consistency on the spelling of the genre and region. Wassoulou, Wasulu and Wassulu can all be found in credible sources. For the purposes of this interview, we’ll go with Wassulu, the way it is spelled in the sleeve notes for Timbuktu.]

Banning Eyre: Oumou, what a pleasure to see you again.

Oumou Sangaré: How are you? It's been a long time.

It has. Am I reaching you in France?

Yes. I'm in full promotion mode now. Have you heard the album?

I certainly have. It's wonderful.

It's the product of confinement. In Baltimore and New York.

You recorded in Baltimore, and I see you worked with Mamadou Sidibé on kamelengoni. I first met him when he came to New York with Coumba Sidibé.

Yes. Do you know that Mamadou was my very first ngoni player. Coumba snatched him from me. [Laughs]

I did not know that.

Yes, he came with her to the United States and after she died, he moved to Los Angeles. I found myself stuck. I spent three months in New York. But then I had had enough of New York. I wanted to live near New York. I love New York. But it's too much. So I went looking for a small house I could buy. A didn't want to be too far from New York, so I looked around in Connecticut, everywhere.

Connecticut. That's where we live. Too bad you didn't move here. We could have been neighbors.

I spent two months there, but I didn't find it in Connecticut. I looked and looked, but finally I found what I was looking for in Baltimore. I found a nice little house there and right away I sent a plane ticket to Mamadou Sidibé. He came and stayed with me for three months, and we created this album in those three months, without stopping. I was far from home. I was full of nostalgia for my children, my country, my family. You can feel the nostalgia in this album.

You can. And you've kept this house in Baltimore?

Yes. It's my vacation home. You have to come visit me in Baltimore.

Count on it. I understand your feelings about New York. But speaking of New York, did you know that tonight, Burna Boy is playing at Madison Square Garden. It's going to be the biggest African concert this country is ever seen. [And it was!] It's a sign of the progress of African music.

Yes, yes, yes. African music has really progressed. The mix with other genres is very strong.

Coming back to your album, I see that you worked with this French producer and guitarist Pascal Danaë. Tell me about him.

We worked with Pascal remotely, online. He was in France, in Paris. He and his group were there. We would send them tracks and they would add things and send them back to us. When it was too much, we would say, "No, no, no. That's a bit much. You have to pull it back." And when it was beautiful, we’d say, "Wow. That is super good. Keep this part, take out that part, but you have to make this part even stronger." That's how we worked online.

Had you worked with him before?

No. This was the first time.

Why did you choose him?

My advisors had worked with him and I really liked what he did. He's a great artist. He has his own group and works constantly. And now I'm very, very happy with the album.

I noticed that Pascal plays a lot of slide guitar. It’s kind of a sonic theme on this album.

I really like that, because the slide and the ngoni make a new sound together. I like to mix things up. I like to discover things.

The ngoni is very percussive, and the slide just flies over top.

It works really well. And what astonished me is that it's been very well received in Africa. We released three songs in they’re very popular. Because I was afraid with the release of the album. How would they receive it? But I had nothing to fear.

I see that this album is back on World Circuit, the label you started with.

Yes I went back home. We've been working together for over 25 years. We've become family. It's nice to go and try something outside. We did magical work with the French. No Format is a small label, but they did fantastic work. Remarkable. It was an important part of my career.

A little vacation, but then you came home.

That's right. A little recreation.

Let's talk about some of the messages on this new album. I was thinking of you as kind of the conscience of Malian society. You always have so much to say to your country. Let's talk about the song “Wassulu Don,” in which you say that the Wassulu region is a “shelter for peace” in Mali.

That's true. Because for me, Wassulu is a region that is extra rich in culture, that has passed its time giving and giving artists like Kaba Sidibé, Coumba Sidibé, Sali Sidibé, Toumani Koné. Wassulu has spent its life giving joy, bringing joy, bringing beautiful things to the rest of the world, so that the world could ask, "What is Wassulu?”

This is why I have created the International Festival of Wassulu. As of today, we have received over 300,000 people over the three days in Yanfolila. You've never seen anything like it. It's the biggest festival in Mali today. It happens in the month of March. Wassulu has been giving all this beauty, and now it's time for the rest of the world to come and discover Wassulu. It's time for the world to come to our home and to know us deeply. So in this song, “Wassulu Don,” I am magnifying Wassulu. I speak about this richness and I invite people to come and discover for themselves.

Sometimes people the judge us. They think of us as people who just make music and do nothing else. But it is the music that has allowed us to develop Wassulu. So come and see the results. Come and discover the power of this music in Wassulu.

Well, you've convinced me. We have to come. The last time we spoke was just as the pandemic was beginning, and you had successfully held the festival. What has happened since?

Even in the midst of the pandemic, the festival happened. People told me, "You can't have this festival." But then the organizers said, "No, Oumou, you have to do it." They formed a commission and came to Bamako to tell me this. They said, "We don't have COVID here. We have lots of sunshine. You must come and see." So we did the festival. It was incredible. We did not miss a year. It's been five years now, and it gets bigger each year.

We created a camping area. But now hotels are springing up in Wassulu like mushrooms. Anyone in Wassulu who has money is building a hotel. You find big hotels being built there now. It's amazing. And it's because of this festival.

The other thing I noticed about this song “Wassulu Don” is that it's kind of a rock song. Heavy guitar. There’s a kind of John Lee Hooker blues-rock feeling to it. It's the most rocking song on the album, and it's the one that you lead with, and the first video you released. Talk about that.

I am a very open musician. Yes, the guitar on that song is very rock. But when that song plays back home, and you see the young people dancing to it in Wassulu, you would not think of it as rock. Or maybe it's because rock music was born in Wassulu. I don't know. But when they dance, the dust rises. At this last festival, we played that song, and you should've seen them dancing, kicking up the dust with their feet. And they were dancing traditional dances. They weren't hearing rock; they were hearing tradition.

That makes sense. I remember going to a hunter's ceremony in Bamako years ago and hearing the donsongonis playing a riff that was exactly like "Smoke On the Water." That was kind of a revelation to me.

Voilà. The origin of rock is in Wassulu, and we didn't even know. I don't play rock. I play traditional music from Wassulu.

There's a very interesting message in your song “Sira.” I understand that you are talking about the children of wealthy, successful people. And you have this line that says, "The baobab’s trunk is smooth, but its fruits are rough."

It's a bit of poetry. How can I explain this? It's a way of saying that everything can change in life. I'm giving advice. For example, when you are going to marry someone, you might think that if they come from a good family they will be a good person. But you can be mistaken that way. In the song I say that appearances can fool you. Nothing is sure in life. Something that appears good can be very, very bad. Life is full of surprises. So pay attention. Don't judge people by where they come from but from their actual behavior. Don't think, "Well, they come from a good family, they must be good, or if they come from a bad family they must be bad. Don't judge that way. Judge by their acts. The good family can produce bad people and the bad family can produce good people.”

Very good. And I hear you telling the children of successful families that they have to earn their own success. Just having rich parents is not enough.

That's right. Exactly.

You have called this album Timbuktu, and in the song by that name, you ask questions. I noticed that often in your songs, you are asking questions of the listener. “Where are the values our ancestors gave us?" and you talk about people being in a "deep sleep." Why are you focusing on Timbuktu at this moment in history?

Because it signifies the situation in my country. I have to ask these questions. Where has all this unhappiness come from? We have to ask ourselves. What has brought us all this misfortune? We have responsibility in history. Why Timbuktu? It's a way of sharing the sadness that has come to Timbuktu. The city has been sacrificed by the jihadists. They have destroyed things that were there for centuries. All the culture that was there was destroyed by people who call themselves Muslims. But it was the chiefs of the Muslim religion who brought Islam to Mali. This has been their home for hundreds of years. Why destroy this? It's a very sad.

I want to share this sadness of the people of Timbuktu with the whole world. Because it touches all of us. UNESCO has recognized Timbuktu. We have to reconstruct this history. This is why I could not give another name to this album if it was not Timbuktu. It's a cry from the heart. You know I'm a grandmother now. And I know that the origin of my grandchildren is Timbuktu. Their mother is an Arab from Timbuktu who my son married.

Fascinating. I remember your son as a very young boy.

Yes he was a baby. But he has grown up and married an Arab woman. So I feel very connected to this historic city of Mali.

There is so much history in Timbuktu. It has changed hands many times in the course of history. Hasn't it? And yet there's a continuity, a great strength there, so I understand why that connection is important for you. On a more personal note, there are two songs here, “Sarama” and “Dily Oumou,” that talk about gossip and jealousy. I have a feeling this is personal for you. Talk about where these two songs come from.

“Sarama” and “Dily Oumou,” if you like, these are songs I sing to pacify myself. Because to carry all these jealousies is heavy. All these prejudices. It is heavy. I wanted to sing to calm myself. And I wanted to sing to calm all the people who are in the same situation as me. People who have followed their star and found a good life, but who are the victims of prejudice and judgment. “Sarama”-- there was a customs officer came to me to say, "Oumou, thank you for singing this song. You were singing this song for me.” I said, O.K. But there are many people who feel this way. It's very heavy to carry this kind of jealousy.

It's important to think about the people who love you. Because there are a lot more people who love you than those who don't. That's what gives me the strength to face all the sorts of problems. That's what gives me energy. It supports me. It calms me. And I hope it calms all those who are in the same situation.

This reminds me of a phrase I heard from a musician in Madagascar. “A tall tree is hated by the wind.”

That's true. Attacked by the wind. I agree. It's universal.

So in connection with that, you have this song “Degui N’Kelena” where you talk about being alone, and a kind of security and peace comes with being alone.

The message I wanted to pass in that song is to tell people to be stronger than their emotions. If you become too angry with someone, if your love has been torn apart, and you become separated and you are not psychologically prepared for it, you can easily fall into depression. No one wants to be alone. But solitude is not a bad thing. You have to be ready. You can't pass your whole life without falling into solitude at some point. You have to be psychologically prepared for that. You may become separated from someone who you have given everything, who you've given all your love, but then you are betrayed. If you are not ready for this you can be hurt. But if you are psychologically prepared, you understand that this is natural. “I can be alone. I am stronger than this.” You need to prepare yourself for this. It's nostalgic. But you have to be ready.

That's a powerful message. If you don't have that strength within yourself, you are vulnerable.

Exactly. You are vulnerable. You can easily fall into a dark place. You have to master your emotions.

You have some familiar messages here too. “Kêlê Magni” is an anti-war song. “Demissimw” is about supporting children, always an important message for Oumou. And “Kanou” returns to the theme of love in the face of societal pressures, forced marriage and polygamy. These are the bedrock ideas in your repertoire.

Yes. Life can be really sweet. You mustn't always dwell on your problems. We have to talk about the reality of love. You have to speak up about things. War is useless. But after you have spoken about the uselessness of war, talk about love, the beauty of life. You have to keep that balance in your life.

At the end of this album, you have this very beautiful a capella song, “Sabou Dogoné.”

That's a traditional song from Wassulu. I took it and transformed it. Because in Wassulu, you sing this song very fast. [Sings] But I took this song and I slowed it down. [Sings softly, slowly, as on the album] There's a very powerful message in the song that I wanted people to understand. [The song is about the search for “hidden knowledge,” found in Wassulu.] Even without understanding the words, I want people to understand what they can, something. That's why I slowed down.

And you return at the end to the wisdom of Wassulu. The album comes full circle. Very nice.

Thank you. It's all the product of confinement.

The silver lining. I understand. I have been hearing similar things from a number of artists that I have interviewed recently. There's a kind of reflection that this period has allowed.

It's true, isn't it?

Oumou, I have to ask. Now that the confinement is ending, when will we see you and your group back on American stages?

We have a tour in October and November. You will see us.

Finally, I mentioned that the Nigerian artist Burna Boy is making history these days. This is an interesting moment for African music, and for those of us who been following African music for almost 40 years, we see just how big this moment is. These young artists are truly writing a new chapter in African music. What's your impression of these artists and what they're doing?

It gives me satisfaction. It's been a long fight. Afropop has been part of that fight. All these years, you've been working to introduce African music in America. So bravo to you. You've been fighting alongside the artists. African artists have truly progressed, but they mustn't forget the role that Afropop has played. You have insisted on presenting African music. Americans don't really need music from the rest of the world, but you have fought for that. You have fought to show the beauty of African culture, which is the origin of so much music in the world.

Very kind of you. At Afropop, we’re coming to a point where it's time to pass the torch to younger hands. The world has changed. The music has changed. We think our program also has to change with the times. We're hoping to find strong new voices and leaders to build on what we have done. It's a challenge to find young people with courage and passion to do that. But we're going to do it.

In sha’allah.

Thank you, Oumou. We will see you in October, if not sooner in Baltimore.

Yes, Baltimore. We’ll have a barbeque in Baltimore!

Perfect.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles