In January, 2011, as the Tahrir Square rebellion in Cairo reached its pinnacle, the role of artists came strongly to the fore. A scraggly young singer/songwriter named Ramy Essam frequently took the stage in Tahrir with his guitar to sing out-and-out protest songs laced with humor and defiance. These songs became iconic anthems of the uprising. Meanwhile, street artist Ganzeer was painting murals around Cairo, including portraits of slain protesters near the places where they died, and creating provocative graphic images that rapidly went viral on social media, posters and T-shirts. Through the work of these and other brave artists, music and visual art were playing an outsize role in the Egyptian Revolution.

A few months later, in July, Afropop spent a month in Cairo. We met Essam in Tahrir at a moment of calm. Adorned with makeshift tents and stages hosting speakers, musicians and seminars of sorts, Tahrir Square felt more like the scene of a town fair than a nexus of revolution. The singer appeared with his guitar and a young woman who translated for him; Essam spoke virtually no English at the time. By then, he had recovered from the injuries he sustained during a day of beating and torture at the hands of the army prior to president Hosni Mubarak’s resignation on Feb. 11. But the story Essam told us that day was bracing. (You can hear some of our interview on the program Egypt 5: Revolution Songs.)

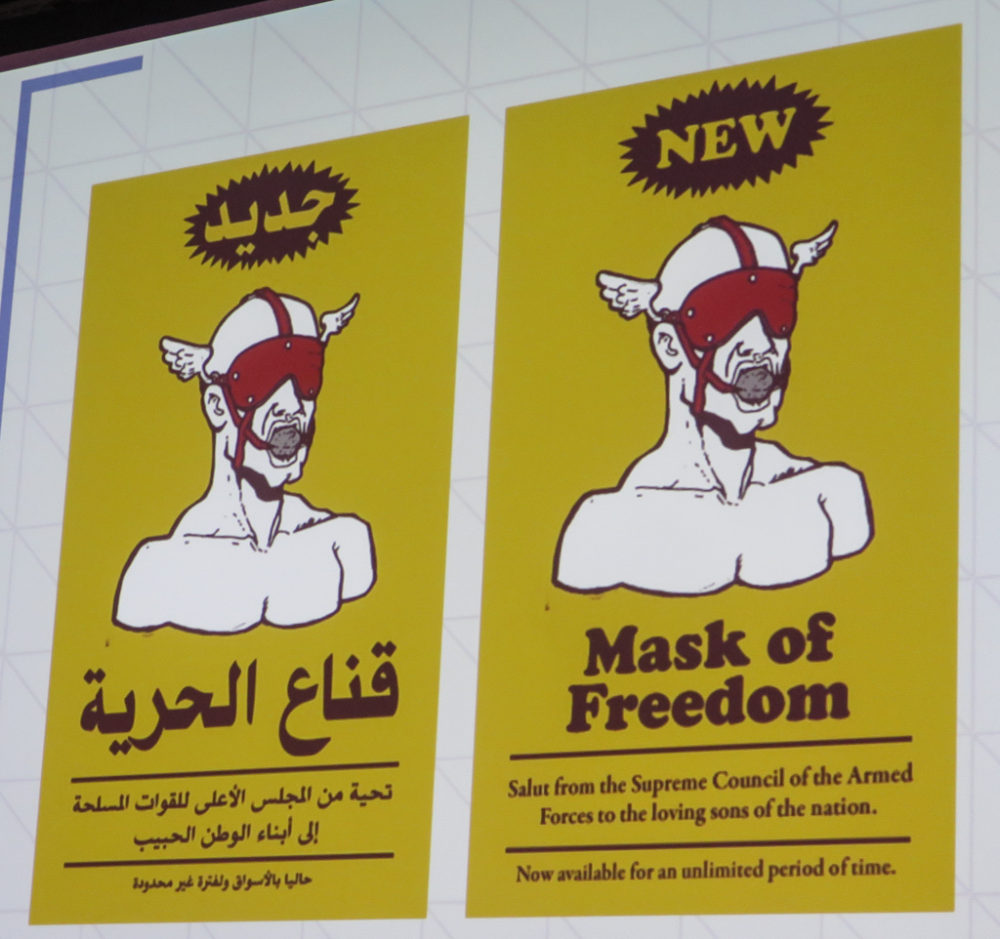

Nine years later, I spoke with Essam by telephone as he prepared for a Jan. 25, 2020, show at Brooklyn's National Sawdust entitled "Tahrir and Beyond." We had not spoken since Tahrir, so I was surprised to hear his fluid English, and was once again riveted by his story. At National Sawdust, the show opened with a presentation by Ganzeer, essentially a multimedia tour of the most memorable images he created during those historic days in 2011. Following Ganzeer, brothers Daniel and Patrick Lazour took the stage with a single nylon-string guitar and sang songs, mostly from their musical theater piece, “I Live in Cairo,” which Ganzeer described as the most effective presentation of what happened during the revolution he had seen—pretty remarkable as the show was created by two young Americans who were not there when the revolution happened!

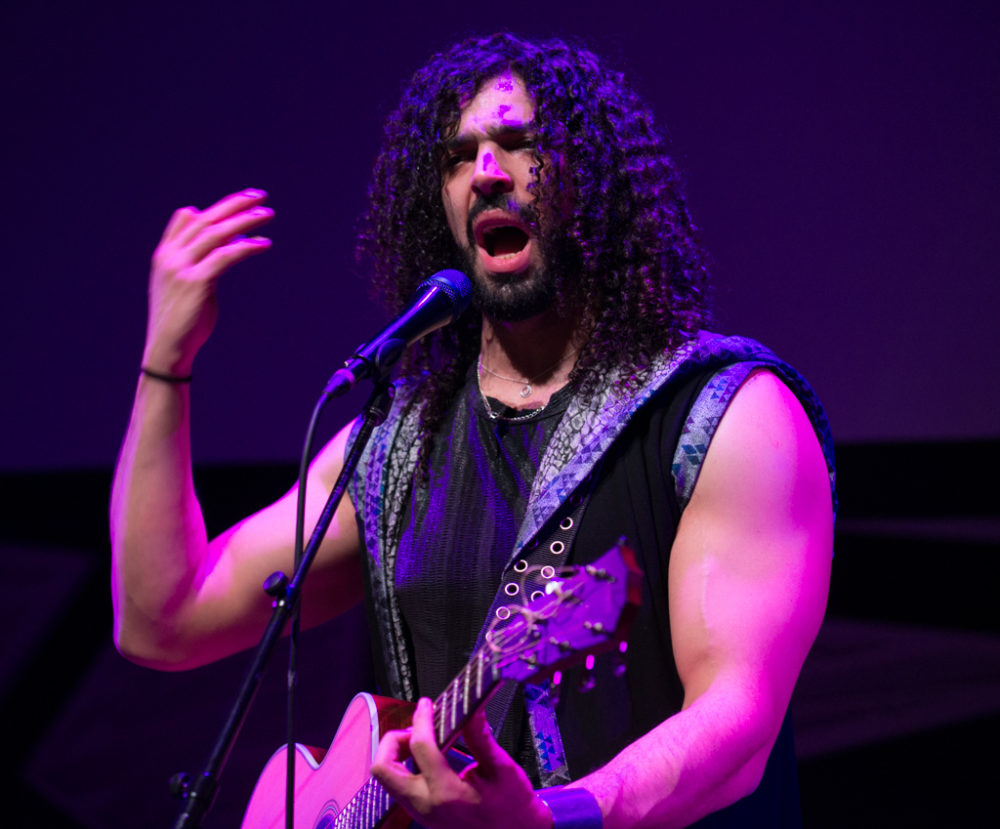

Suffice it to say, it was a fascinating evening, culminating in an incendiary set by Ramy Essam and his band—essentially a rock power trio whose sound ranged from Pink Floyd expansiveness to thrash metal intensity, with Essam’s gravelly baritone easily commanding center stage throughout. The goal of the evening was to commemorate the “spirit of the revolution.” Anyone who has followed events in Egypt even at the most cursory level knows that the goals of the Tahrir revolutionaries have not been realized—far from it! So the idea here was to remember, to rekindle strength for the long fight ahead, and to honor the sacrifices made during the period of hope that began on Jan. 25, 2011 and ended with the swearing-in of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi on June 8, 2014.

The crowd, mostly Egyptians, that packed National Sawdust got the message loud and clear. Their joy, pain, hope and resolve were palpable, especially during Essam’s electrifying set. What follows is my conversation with Essam before the show, and photographs I took during it.

Banning Eyre: Ramy, thanks for making time.

Ramy Essam: It's my pleasure.

We actually met in Tahrir Square in 2011.

Oh really?

Yes. It was in July, and we did an interview right amid the tents in the square. It was a memorable experience for me. Obviously, there’s been a lot of water under the bridge since then…

Oh man, yes. Volcanoes!

For one thing, you're speaking very nice English now.

That's right. If you met me in 2011, I wasn't speaking any English. I remember. But now, we can handle that.

Maybe I'll just start with little biographical stuff. Where have you been living since then?

I've been in both Sweden and Finland, but also traveling a lot here and there.

So, in Sweden and Finland you learned such good English?

Actually it happened in Sweden. My English wasn't good, as you know. And I had to decide, should I speak Swedish or should I improve my English? And everyone there likes to speak English, to practice their second language. So it happened like this.

It's interesting that you are in Sweden. We did an edition of our radio program on the African music scene in Sweden recently. It seems there’s a lot going on there.

That’s true. Where do you live now?

In Connecticut, outside New York. And I will be coming in for the show on Saturday.

That's great. I love that. You're going to love it. It's going to be a special night.

Tell me about the show.

O.K. It's the 25th, so it's the 9th anniversary of the revolution, and the idea was to make something that day to be a reminder for us [Egyptians] before anybody, and also open to others. The fight is not over. I had this idea much earlier in the year, but it really became serious when I started to talk to Ganzeer. Ganzeer is one of the main visual artists that played an important role in our movement. And he is in exile in the States at the moment. So we talked and put ideas together, and here we are. And he will be there on Saturday, talking, and giving an audiovisual presentation of his work. Then there is also the Lazour brothers, and we're so happy having them.

Tell me about them.

They are Americans, originally from Lebanon. And they are two brothers who wrote a recent, very successful musical called, We Live in Cairo. I think they have been writing this theater piece for six or seven years. And Ganzeer, was part of our movement, he went to the show, and he was so impressed how they really managed to get the work done and reflect on Tahrir Square and the revolution, and all made by people who were living in the states, who were not living in Egypt during the revolution. It was very impressive. So they wrote this theater piece and they wrote all the music too. Both of them are singers, and they play guitar, and they will be the opener after Ganzeer.

Will you perform with a band, or just solo with your guitar as you did during the revolution?

No, no, no. I have my band.

What's your band like? I've been listening to a number of tracks on your site, and watching some of your videos, and I notice that you're using different kinds of accompaniment.

Nice. The people that recorded the music were in Sweden. These were Swedish musicians in Stockholm. Especially the album Resala Ela Magles El Amn, the one that is on Spotify and is the music for a lot of videos. But my band, they are Americans. They live in New York. And they are badass Brooklyn musicians who all went to Berklee. You will enjoy them a lot. They are great.

I bet I will. So you’ve been spending time in New York as well.

Yes. New York is always in the equation because the band lives here. So even if I don't have a gig in New York, I will always come here to rehearse, and then hit the road and start my tour. I always come back to New York.

Great. Well, next time, we will interview in person.

Oh yeah. I like New York so much. It's like Cairo in a way. Since day one, I always say that if Cairo was an American city, it would be New York. You've been there, so you know what I'm talking about.

Yes, it does have some of that frantic, crazy energy. Although the car horn language is different.

[Laughs] The car horns. Yes. Well, they are not the same, because Cairo is multiplied by 10 in every way. The noise pollution and so on…

But I know what you're saying about the energy.

New York is also a city that doesn't sleep. That's why I like it. I haven't been back to Egypt since I left.

When did you leave?

I stayed through 2014. I left on Aug. 8, 2014. That's the date. Sisi was already the president. He became the president in June. So I was still in Egypt when he became the president.

I understand that things have now really gotten bad for creative expression and any sort of opposition. But I imagine it was pretty bad under Morsi as well.

It was bad under all of them. But always, always the worst under the military control.

So when you look back on that moment nine years ago when people in the square were chanting in favor of the military, and feeling like they might be part of the solution, does it seem like that was just an illusion?

Oh, I never believed that. For me, it was just a lie, bullshit. A big lie. My torture experience was like a gift from them, from the revolution for me to really understand from very, very early that they are the real evil. All of it is in this organization is called the military, and the Military Council especially. But from the beginning, even before the torture day, anybody that was in Tahrir Square during Mubarak, especially during the Battle of the Camels…

Yes, I remember the images of camels charging at protesters. That was horrifying.

The Battle of the Camels was the real, real sign for most people that the army was not really supporting the revolution. They were just watching from a distance and seeing who will win. And the one that will win, they will just push aside. And they were so happy in seeing somebody get rid of Mubarak and his sons, because that's exactly what they wanted.

But they didn't want the revolution that accomplished that goal.

Exactly. So when they saw a revolution going on, they said, "We'll just wait. We will just watch from a distance.” These kids—in their opinion, for sure—would do something, and then they would just take over at the right moment. And that's what they did.

I remember the time when we were there in July, 2011. We spent a month in Cairo and talked to a lot of people. There hadn't been any elections yet, so there was still a lot of hope that maybe things were going to be O.K.. There was definitely a fear of what an election might bring, but that hope was still alive.

Oh yeah, come on, brother. We were all full of hope!

So even though you didn't trust the military, you shared that hope.

Yes. We still had the hope that we would make it happen. We didn't even lose hope until 2013. I even haven't lost hope today. But you know what I mean.

Right. You mean hope that the idea was good work in the short term. What was the straw that broke the camel's back—sorry for the metaphor—for you?

It was many things. Many things. O,K., basically, realizing the fact that this naïve idea that we had in the beginning that we could break the dam that corrupted Egypt in just one or two years. This was a very, very euphoric, naïve idea. And to realize that we were not ready for the taking over. This also became clear in 2013. When Mubarak left, and then the military left, and then the Muslim Brotherhood came and left, we saw that even though we were playing a very important role in what was going on, we didn't have a clear plan. And you can put on top of that, the main, main reason that we realized it would take time was when we realized how much everyone was exhausted after fighting for three years.

People in the revolution gave their life to the revolution. Literally, people died. But also, people that didn't die, they also gave their life to the revolution one way or another. Either through losing studies, losing jobs, losing partners, family members, even losing their eyes. Humans got exhausted. It was really nothing more than that. Many people lost hope. Some did not, but at the same time, many people lost hope. I still don't want to see it that way. I just see it that they are tired and exhausted. That's very normal for human beings, and one day they will come back again. Maybe, they already did their part, and now the turn comes to the next generation. But this generation gave three years of their life. They are tired.

It must be so disheartening for those who are still there. I gather that it's very much clamped down these days.

Oh yeah. It's very dark. Very dark for everybody that's there now. That's true.

So sad. Let me ask you about some of your songs. I've been watching some of your videos. Let's start with the one about Sudan, “Rise Up Sudan.” I know that the histories of Sudan and Egypt are so closely tied together, and there so much tragedy in both stories. Tell me about that song.

I will tell you. First of all, when the Sudanese revolution started… Like you said, they are neighbors and we would love to see them free also. And to be in a better place. But when it started, there was a wave of hate, maybe not hate, disappointment from their side at the Egyptians. Because when the Egyptian revolution was going on, the Sudan people went crazy, supporting and doing everything they could. They were even going out on the street to support the revolution in Egypt. Not just against Mubarak, but at other times too. And they expected from us to do the same.

Ah ha.

But as we were just saying, Egyptians is in a very harsh time—the movement in Egypt… We don't even go out ourselves to make change and continue what we started. People are taking a real break. Plus, Sisi is going crazy and arresting everybody. So this picture, you can't just tell it to somebody living abroad so that someone who is not Egyptian will understand. So the people in Sudan got disappointed, and there was some hate speech on social media as well. And from that moment I was, like, thinking I would love to make a song. I was already thinking about it. But I have a Sudanese friend who used to live in Egypt, and I was calling him just ask his opinion about that. And he said, “Man, I was going to call you. I would love to see you singing to our revolution." But at that time, I didn't have lyrics. You know I don't write my lyrics myself. Sometimes I do, but mostly not.

You work with a lyricist.

I mostly work with a lyricist. Like 80 percent. And then maybe 20 percent I write myself. But the majority, for sure, I get the lyrics and then I compose the music. So this time, I used lyrics written by my friend who is in jail because of the song “Balaha” that I did with him. He's serving a three-year sentence in Tora Prison by a military court because of that song.

Tell me about Galal.

He's an Egyptian poet and my friend who wrote the words for many of my songs. So the lyrics are written by Galal El Behairy in an Egyptian jail.

That's amazing.

So then I composed it and produced it. We produced it in Sweden, in Stockholm with my producer, Johan Carlberg.

Like the beer without the “s.”

Yes, it is the beer without the “s.” Beautiful. You nailed it. We always joke about that.

So you say that Galal was prosecuted because of the song “Balaha.” Tell me about that song.

“Balaha” came before the elections when Sisi wanted to run for his second four years. Times in Egypt were very crazy. There wasn't even much opposition. Certainly not like before, especially with the music. And I said, I want to do something. This was my goal and when I told the idea to Galal, he supported it and said he wanted to do with me. We wanted to raise awareness and make people think about all the disadvantages and bad things that had happened in the first four years. Wanted to make a debate, because everything was a still river. Nothing was moving in opposition or politics. So we just wanted the people to talk about it and think about it, and we succeeded in making a big hit in a few days. There were millions of views. And it provoked the government in the extreme, and then they arrested my team.

What does Balaha mean?

Balaha is actually the fruit, the date. But it was a song was criticizing the government.

It's good that you put English subtitles on the videos. Helps people like me get the message.

Yes, exactly. That's one of the things that I learned in the last five years. And when you come to the show, even when I perform now, I sing in English as well, maybe 20 percent of the show. But in this show, I will do only one or two songs in English, because this is for the day for the Egyptian Revolution, so I won't do many English songs. But even when I don't sing in English, in the live shows I explain everything. You will see.

It seems as though artistically now your form is songs and videos rather than albums. Is that right?

Yes. I have released albums, but I release music with strategy that you just mentioned. I always try to keep a video in the equation, because this is the industry now. That's how it works with me and my people. And I will try to keep it up.

They are very cool videos. There's another one I want to ask you about that I really like: “Lessa Bahinlha.”

Yes. That's the one where I'm just playing the guitar, sitting in the snow.

Exactly. Beautiful singing on that. Tell me about it.

“Lessa Bahinlha” means "longing for her,” and it's basically the song about a person who is missing the home country, missing the street, missing the food, missing the smell, missing the family, the friends. The ex, the old partner. The old life. When you're in exile, you just lose it all. So it's a love song for home, for your home country. I love it. I will perform it in the gig for sure.

Let me ask you about another one, “Deboura we Short we Cap.”

This is one of the early, early songs period from 2011. It is just making fun of the cops, the police. It was very important to make fun of the bad cops.

Are there any other songs you particularly want to tell me about?

There's one other we should mention because is considered one of my biggest hits, even though for me, I have better ones. But you don't choose your hits. I still like it. But is not in my top three. It's called “Segn Bel Alwan.” It's a very important song. It's written by Galal again, from prison, and it's about the women and girls in prison. It's highlighting the role of girls and women in our revolution. It's a man's country, a macho, masculine culture, as you know. So highlighting the women’s and girls’ role was very important—especially when coming from a male voice, admitting that. So for all the idiots who don't believe in equality, and that were all the same and capable of doing the same thing, the song is extremely important.

So Galal is still in prison today.

He's been in for a year and a half.

So to what extent can people in Egypt now see your videos and hear your music? Do you hear from them?

Oh yeah. Definitely. The internet is not blocked. But the problem is that if they know that you are doing that, then you will be in trouble.

So people have to literally hide away to watch your videos?

Oh yes. And I don't know if they're doing this at the moment, but when there's an emergency, a political situation that makes them panic a little bit, especially what happened three or four months ago when the movement was trying to take Sisi down again, they give the police and military permission to search people's mobile phones.

Ah!

So you know Cairo. There are checkpoints here and there and everywhere in downtown. And then they will stop you take your ID, they will take your phone and force you to give your password or your print, and then they will just keep scrolling and checking your phone. It's ridiculous. And if they see a song or a picture or post, they will ask you about it. So people have been arrested at checkpoints because they have a T-shirt that says something political, or even just something they don't like.

Wow. That will have a chilling effect, won’t it? Well, with things at such a dark point now, I suppose it's hard to imagine what progress would even look like. You say you still have hope, but what does hope look like in 2020?

We don't have the know-how, how to come out of this. If I had it, I would publish it. The point is the reason I have hope is that I'm a lucky person as an artist, doing what I'm doing. I get messages from the young generation, from people who are like 9 years old or 11, 12, 14. Just talking about freedom and a better future and a better Egypt, all topics that I never talked about till I was 20. Just to know that the songs and all kinds of opposition art are reaching the young generation, then you can believe that the future will be better. Because we didn't have that before. We didn't have this kind of number of young people who have access to political art. That didn't happen before.

Well, that's a grain of hope. And I guess it's human nature to have some kind of hope, even if you don't see the way ahead.

Yeah, if I don't have hope I would stop. And I won't stop. I need my hope.

I suppose we’re in a somewhat analogous situation in this country. It's a dark time that we didn't imagine.

You didn't expect this would happen in your lifetime. Yeah. Crazy. You didn't expect that that would happen in your lifetime. That you would have this clown as your president. It's insane.

Well, we all have our challenges. I really appreciate your taking time to talk. I'll be sure to say hello on Saturday. I really admire what you're doing, and I'm very impressed with your English.

It's become a language I speak. I speak it all the time.

Well, it's impressive.

That makes me happy.

I remember our meeting very well. There was a woman who was translating for you.

Yes. I couldn't really handle an interview at any level. I always had to have an assistant translating.

And it was such a strange moment then. It was July, super hot, and during Ramadan. Things were peaceful. The square felt almost like a street fair or something.

[Laughs]

It was surreal. And then I remember when the police cleared the square a few days later. We were lucky to be there when we were. We were able to move around quite easily and talk to many people. Well, thanks again. See you at the show.

Thanks for the interview. See you soon.